The world is vast and incomprehensible, but a lifetime’s study may begin to illuminate its hidden depths. At least it’s been that way for the hero of Shuichi Okita’s latest attempt at painting the joys and perils of a bubble existence. Mori, The Artist’s Habitat (モリのいる場所, Mori no Iru Basho) revolves around the real life figure of Morikazu Kumagai (Tsutomu Yamazaki), a well respected Japanese artist best known for his avant-garde depictions of the natural world, as well as for his eccentric personality. When we first meet him the early 1970s, Mori (a neat pun on his given name which uses the character for “protect” but also means “forest”), is 94 years old and has rarely left his beloved garden for the last 30 years. A man out of time, Mori’s world is however threatened by encroaching modernity – a gang of mobbed up property developers is after his land and is already in the process of constructing an apartment block that will rob Mori’s wonderful garden of its rightful sunlight.

The world is vast and incomprehensible, but a lifetime’s study may begin to illuminate its hidden depths. At least it’s been that way for the hero of Shuichi Okita’s latest attempt at painting the joys and perils of a bubble existence. Mori, The Artist’s Habitat (モリのいる場所, Mori no Iru Basho) revolves around the real life figure of Morikazu Kumagai (Tsutomu Yamazaki), a well respected Japanese artist best known for his avant-garde depictions of the natural world, as well as for his eccentric personality. When we first meet him the early 1970s, Mori (a neat pun on his given name which uses the character for “protect” but also means “forest”), is 94 years old and has rarely left his beloved garden for the last 30 years. A man out of time, Mori’s world is however threatened by encroaching modernity – a gang of mobbed up property developers is after his land and is already in the process of constructing an apartment block that will rob Mori’s wonderful garden of its rightful sunlight.

Okita introduces us to Mori through an amusing scene which finds the Japanese emperor “admiring” one of his artworks only to turn around in confusion and ask how old the child was that made this painting. Spanning the Meiji and the Showa eras, Mori’s artwork is defined by its bold use of colour and minimalist aesthetic which outlines only the most essential elements of his subjects. As his wife of 52 years, Hideko (Kirin Kiki), explains to the various visitors who turn up at Mori’s studio/home hoping to commission him, Mori only paints what he feels like painting when he feels like painting it. Getting him to do anything else is a losing battle.

Painting mainly at night, Mori spends his days observing the natural world. Wandering around his garden he stops to sit in various places, gazing at the ants, and playing with the fish he put into a small pond dug way down into the earth over a period of 30 years. Despite his distaste for “visitors”, Mori has consented to be the subject of a documentary, followed around by a photojournalist (Ryo Kase) and his assistant (Kaito Yoshimura) keen to capture him in his “natural habitat”. The photographers, natural “shutterbugs”, gaze at Mori in the same way he gazes at his trees and insects. An irony which is not lost on the reticent artist.

Okita neatly symbolises Mori’s world as a place out of time by hovering over his desk on which lies a disassembled pocket watch. Eventually the watch will be repaired and time set back in motion but until now Mori’s garden has been a refuge of natural pleasures which itself contains the world entire. Receiving a surprise visitation from a supernatural being (Hiroshi Mikami), Mori is given an opportunity to explore the universe but turns it down. Firstly he doesn’t want to leave his wife on her own or see her “tired” by his absence, but secondly his garden has always been big enough for him and given thousands of years he fears he may never be able to explore it fully.

The garden, however, may not survive its owner. The 1970s, marked by early turmoil, later became a calm period of rising economic prosperity in which society began to move away from post-war privation towards economic prosperity. Hence our big bad is a property developer set on building apartment blocks – a symbol and symptom of the move away from large multi-generational homes to cramped nuclear family modernity. Unbeknownst to Mori, his garden has become a focal point for the environmental protest movement who have begun to set up signs and slogans around his home attacking the property developers for ruining a national landmark which has important cultural value in appreciating the work of one of Japan’s best known working artists.

Having lived through so much turmoil, Mori takes this in his stride. He knows his garden won’t last forever, and is resigned to the nature of the times. Mori may prefer to spend his days in quiet contemplation resenting the constant interruptions from all his “visitors” but makes time to talk seriously with those who seek his guidance such one of the developers (Munetaka Aoki) who’s brought along one of his son’s drawings, convinced that he must be a “genius”. Mori takes one look and tells him frankly that it’s awful, but adds that that’s a good thing – those with “talent” rarely do anything of note and even if it’s “bad” art is still art. Nevertheless there are those who try to profit from his work for less than altruistic purposes – the hand-painted nameplate from outside the house is forever being stolen and he’s constantly petitioned to provide his services in service of someone else’s business.

Okita’s characterisation of the later life of a famous artist is another study of genial eccentricity as its hero commits himself fully to living in a way which pleases him, only bristling at those who describe his gnome-like garden presence as resembling a “Chinese Hermit Sage”. Mori himself is, of course, another living thing enjoying the natural world to its fullest and if it’s true that his time is ending there is something inescapably sad in looking up from the shadows of apartment blocks and finding nothing but lifeless concrete.

Screened at the 20th Udine Far East Film Festival. Mori, The Artist’s Habitat will also be screened as the opening gala of the 2018 Nippon Connection Japanese film festival, and will receive its North American premiere at Japan Cuts in July where Kirin Kiki will also receive the 2018 Cut Above Award.

Original trailer (no subtitles)

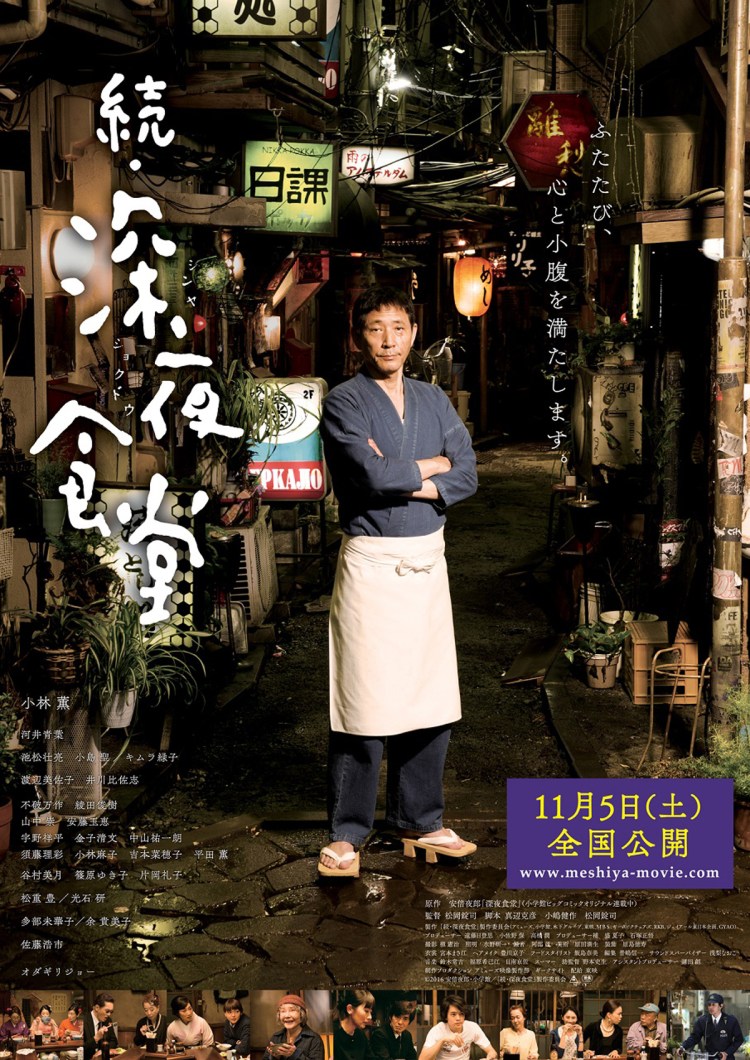

The Midnight Diner is open for business once again. Yaro Abe’s eponymous manga was first adapted as a TV drama in 2009 which then ran for three seasons before heading to the

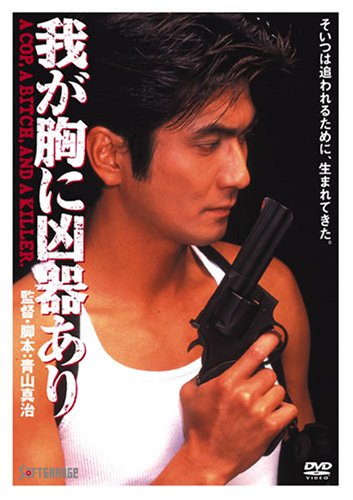

The Midnight Diner is open for business once again. Yaro Abe’s eponymous manga was first adapted as a TV drama in 2009 which then ran for three seasons before heading to the  Shinji Aoyama would produce one of the most important Japanese films of the early 21st century in Eureka, but like many directors of his generation he came of age during the V-cinema boom. This relatively short lived medium was the new no holds barred arena for fledgling filmmakers who could adhere to a strict budget and shooting schedule but were also aching to spread their wings. After a short period as an AD with fellow V-cinema director now turned international auteur Kiyoshi Kurosawa, Aoyama directed his first straight to video effort – the sex comedy It’s Not in the Textbook!. Released just after his theatrical debut, Helpless, A Weapon in My Heart (我が胸に凶器あり, Waga Mune ni Kyoki Ari, AKA A Cop, A Bitch, and a Killer) is a more typically genre orientated effort with its cops, robbers, and femme fatale setup but like the best examples of the V-cinema trend it bears the signature of its ambitious director making the most of its humble origins.

Shinji Aoyama would produce one of the most important Japanese films of the early 21st century in Eureka, but like many directors of his generation he came of age during the V-cinema boom. This relatively short lived medium was the new no holds barred arena for fledgling filmmakers who could adhere to a strict budget and shooting schedule but were also aching to spread their wings. After a short period as an AD with fellow V-cinema director now turned international auteur Kiyoshi Kurosawa, Aoyama directed his first straight to video effort – the sex comedy It’s Not in the Textbook!. Released just after his theatrical debut, Helpless, A Weapon in My Heart (我が胸に凶器あり, Waga Mune ni Kyoki Ari, AKA A Cop, A Bitch, and a Killer) is a more typically genre orientated effort with its cops, robbers, and femme fatale setup but like the best examples of the V-cinema trend it bears the signature of its ambitious director making the most of its humble origins.

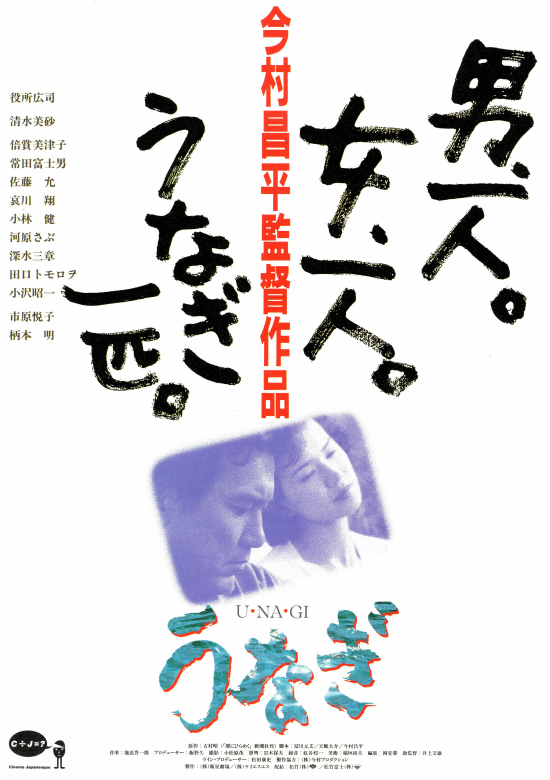

Director Shohei Imamura once stated that he liked “messy” films. Interested in the lower half of the body and in the lower half of society, Imamura continued to point his camera into the awkward creases of human nature well into his 70s when his 16th feature, The Eel (うなぎ, Unagi), earned him his second Palme d’Or. Based on a novel by Akira Yoshimura, The Eel is about as messy as they come.

Director Shohei Imamura once stated that he liked “messy” films. Interested in the lower half of the body and in the lower half of society, Imamura continued to point his camera into the awkward creases of human nature well into his 70s when his 16th feature, The Eel (うなぎ, Unagi), earned him his second Palme d’Or. Based on a novel by Akira Yoshimura, The Eel is about as messy as they come.