What happens if you call the bluff of those who thought they could take your complicity for granted? As it turns out, at least in the case of a small provincial outpost in Isshin Inudo & Shinji Higuchi’s lighthearted historical drama The Floating Castle (のぼうの城, Nobo no Shiro), something and nothing. Inspired by a real life incident which took place in 1590, 10 years prior to the era defining battle of Sekigahara, the film asks how far standing up to corrupt authority will get you but as history tells us this this is the twilight of the Sengoku warring states period and in the end any victory can at best be only partial and temporary.

With Hideyoshi Toyotomi (Masachika Ichimura) poised to unify all of Japan under his rule he turns his gaze towards Hojo, the last remaining hold out in the East of Japan. The small castle of Oshi is asked to commit its forces to protecting the main castle at Odawara where lord Ujinaga (Masahiko Nishimura) is to meet with the head of the clan which has decided to resist the Toyotomi invasion. Ujinaga meanwhile is privately doubtful. He knows they do not have the manpower to protect themselves and the only viable course of action is immediate surrender though he cannot of course say this openly even if buffoonish lord in waiting Nagachika (Mansai Nomura) is brave enough to raise the idea of neutrality in front of the messengers. Preparing to head to Odawara, Ujinaga tells his closest retainers to strengthen defences but to open the castle should the enemy approach while revealing that he plans to write to Hideyoshi, whom he apparently knows personally, and privately pledge allegiance in order to avoid destruction.

Nagachika, however, eventually makes the decision to resist following the arrogant entreaty from Natsuka (Takehiro Hira), the right-hand man of the Toyotomi retainer leading the assault, Mitsunari Ishida (Yusuke Kamiji). He does this largely because Natsuka makes the unreasonable demand that they surrender their princess, Kai (Nana Eikura), herself a fearsome warrior though somewhat sidelined here relegated to the role of contested love interest, to be sent to Hideyoshi as a concubine but also correctly reads that Natsuka and Ishida are overreaching and actually have little more than their bluster to leverage other than the 20,000 men standing behind them which they may not know how to use. Nagachika may play the clown, but he’s not stupid and knows that the 20,000 men are there for the purposes of intimidation and are not expecting a force of a mere 500 to tell them where to go so it stands to reason to think they are not entirely prepared for battle.

In this he’s mostly correct. Hideyoshi has essentially given Ishida, previously in finance, an easy ride to improve his reputation among the other lords instructing the more experienced Yoshitsugu Otani (Takayuki Yamada) to ensure he comes back painted in glory. Otani had said that others admired Ishida for his “childlike sense of fair play”, but his sense of fair play is often childish as in his gradual realisation that everyone is surrendering to him because of the 20,000 men rather than his prowess as a general annoyed with his enemies for backing down from a challenge which is why he sends Natsuka to alienate Nagachika hoping to provoke a battle which no rational person could ever describe as “fair”. Having assumed that Nagachika would back down or that the castle would be easy to take with only 500 country bumpkin soldiers defending it, the Toyotomi are in for a rude awakening discovering the extent of the counterstrategies in place to protect the small provincial outpost, forced into a humiliating defeat licking their wounds from a nearby hill.

But then, as Ishida manically proclaims power comes from one thing, gold, using his vast resources to dam two nearby rivers and then burst them to drown the town as Hideyoshi had done once before. Designed by effects specialist Higuchi the flooding of the town is indeed terrifying, a spectacle which delayed the film’s release as the eerie similarities with the catastrophic tsunami of the year before may have been too traumatic for audiences, and speaks to nothing if not Ishida’s intense cruelty in which he is willing to go to any lengths in order to win even destroying the lives of innocent farmers far removed from these petty samurai games. As the film would have it, his arrogance and entitlement eventually come for him, his trap turned back on himself after an ill-advised potshot at Nagachika, a natural leader beloved by all because rather than in spite of his deceptive clownishness, causes disillusionment with his leadership.

In any case, we already know how this story ends, Ishida is defeated at Sekigahara and beheaded in Kyoto. Nagachika’s victory can be only partial and in fact does not even win him the thing he went into battle for even if he strikes a blow at corrupt government in refusing to simply give in to intimidation, calling their bluff and showing them they cannot continue to push smaller clans around solely with the threat of extinction. In the end they are all at the mercy of their superiors, a truce imposed and imperfect to each side in an act of compromise which spells the end of an era many of those surviving the battles voluntarily renouncing samurai status as if realising their age is drawing to a close, Nagachika proved on the right of history in cultivating links with the Tokugawa soon to take the Toyotomi’s place as rulers of a unified Japan. His resistance was then not foolhardy but justified, necessary, and principled in standing up to injustice even if it could not in the end be fully stopped.

The Floating Castle streamed as part of Japanese Film Festival Online 2022.

International trailer (English subtitles)

Every love story is a ghost story, as the aphorism made popular (though not perhaps coined) by David Foster Wallace goes. For The Tale of Nishio (ニシノユキヒコの恋と冒険, Nishino Yukihiko no Koi to Boken), adapted from the novel by Hiromi Kawakami, this is a literal truth as the hero dies not long after the film begins and then returns to visit an old lover, only to find her gone, having ghosted her own family including a now teenage daughter. The Japanese title, which is identical to Kawakami’s novel, means something more like Yukihiko Nishino’s Adventures in Love which might give more of an indication into his repeated failures to find the “normal” family life he apparently sought, but then his life is a kind of cautionary tale offered up as a fable. What looks like kindness sometimes isn’t, and things done for others can in fact be for the most selfish of reasons.

Every love story is a ghost story, as the aphorism made popular (though not perhaps coined) by David Foster Wallace goes. For The Tale of Nishio (ニシノユキヒコの恋と冒険, Nishino Yukihiko no Koi to Boken), adapted from the novel by Hiromi Kawakami, this is a literal truth as the hero dies not long after the film begins and then returns to visit an old lover, only to find her gone, having ghosted her own family including a now teenage daughter. The Japanese title, which is identical to Kawakami’s novel, means something more like Yukihiko Nishino’s Adventures in Love which might give more of an indication into his repeated failures to find the “normal” family life he apparently sought, but then his life is a kind of cautionary tale offered up as a fable. What looks like kindness sometimes isn’t, and things done for others can in fact be for the most selfish of reasons. There are few things in life which cannot at least be improved by a full and frank apology. Sometimes that apology will need to go beyond a simple, if heart felt, “I’m Sorry” to truly make amends but as long as there’s a genuine desire to make things right, it can be done. Some people do, however, need help in navigating this complex series of culturally defined rituals which is where the enterprising hero of Nobuo Mizuta’s The Apology King (謝罪の王様, Shazai no Ousama), Ryoro Kurojima (Sadao Abe), comes in. As head of the Tokyo Apology Centre, Kurojima is on hand to save the needy who find themselves requiring extrication from all kinds of sticky situations such as accidentally getting sold into prostitution by the yakuza or causing small diplomatic incidents with a tiny yet very angry foreign country.

There are few things in life which cannot at least be improved by a full and frank apology. Sometimes that apology will need to go beyond a simple, if heart felt, “I’m Sorry” to truly make amends but as long as there’s a genuine desire to make things right, it can be done. Some people do, however, need help in navigating this complex series of culturally defined rituals which is where the enterprising hero of Nobuo Mizuta’s The Apology King (謝罪の王様, Shazai no Ousama), Ryoro Kurojima (Sadao Abe), comes in. As head of the Tokyo Apology Centre, Kurojima is on hand to save the needy who find themselves requiring extrication from all kinds of sticky situations such as accidentally getting sold into prostitution by the yakuza or causing small diplomatic incidents with a tiny yet very angry foreign country. “Being good”. What does that mean? Is it as simple as “not being bad” (whatever that means) or perhaps it’s just abiding by the moral conventions of your society though those may be, no – are, questionable ideas in themselves. Mipo O follows up her hard hitting modern romance The Light Shines Only There by attempting to answer this question through looking at the stories of three ordinary people whose lives are touched by human cruelty.

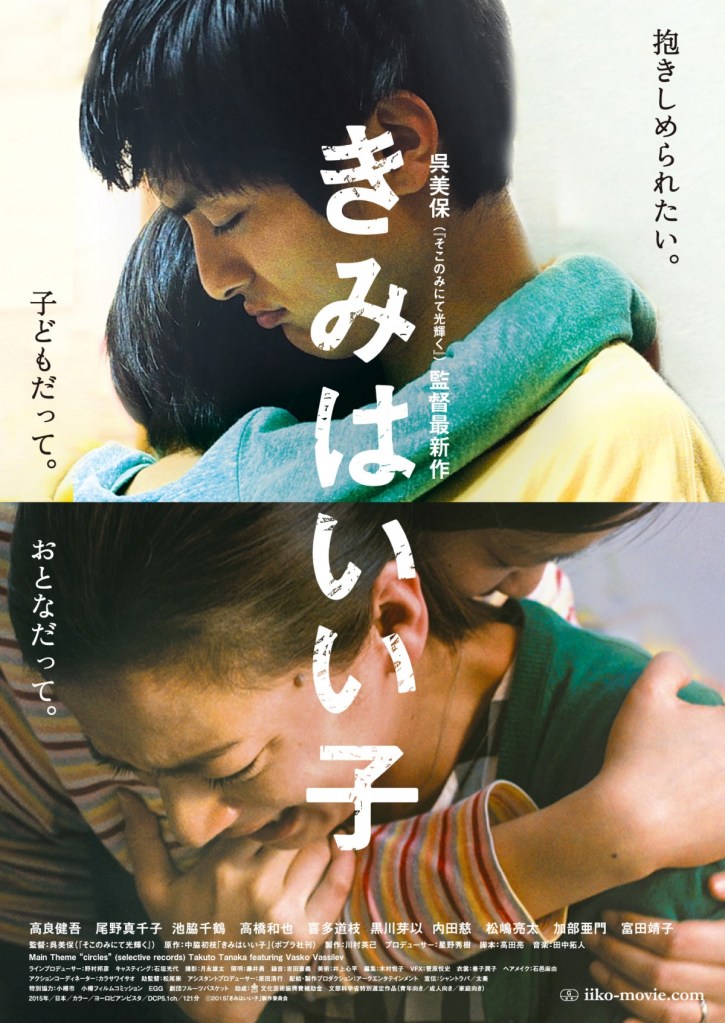

“Being good”. What does that mean? Is it as simple as “not being bad” (whatever that means) or perhaps it’s just abiding by the moral conventions of your society though those may be, no – are, questionable ideas in themselves. Mipo O follows up her hard hitting modern romance The Light Shines Only There by attempting to answer this question through looking at the stories of three ordinary people whose lives are touched by human cruelty.