Random penguins might be the very opposite of a problem, but what exactly does it all mean? Tomihiko Morimi has provided the source material for some of the most interesting Japanese animation of recent times from Masaaki Yuasa’s wonderfully surreal Tatami Galaxy and Night is Short, Walk on Girl, to the comparatively calmer Eccentric Family. Hiroyasu Ishida’s adaptation of Morimi’s Penguin Highway (ペンギン・ハイウェイ) may be a far less abstract attempt to capture the author’s unique world view than Yuasa’s anarchic psychedelia, but preserves the author’s sense of every day strangeness as an ordinary primary school boy’s peaceful life is suddenly derailed by the appearance of random penguins in a small town way in land in the middle of a hot and humid Japanese summer.

Random penguins might be the very opposite of a problem, but what exactly does it all mean? Tomihiko Morimi has provided the source material for some of the most interesting Japanese animation of recent times from Masaaki Yuasa’s wonderfully surreal Tatami Galaxy and Night is Short, Walk on Girl, to the comparatively calmer Eccentric Family. Hiroyasu Ishida’s adaptation of Morimi’s Penguin Highway (ペンギン・ハイウェイ) may be a far less abstract attempt to capture the author’s unique world view than Yuasa’s anarchic psychedelia, but preserves the author’s sense of every day strangeness as an ordinary primary school boy’s peaceful life is suddenly derailed by the appearance of random penguins in a small town way in land in the middle of a hot and humid Japanese summer.

Aoyama (Kana Kita) is, as he tells us, “very smart”. He thinks its OK to tell us this because unlike some of his classmates he isn’t conceited, which is what makes him so great. He’s absolutely positive that he’s going to become an important person in the future and can’t wait to find out just how amazing he’s going to be once he’s grown up. Aoyama is also sure that crowds of girls will be lining up to marry him, but they’re all out of luck because he already has a special someone in mind – the friendly young receptionist from the dentist’s (Yu Aoi) who has been coaching him at chess and just generally hanging out with him chatting about life.

Everything begins to change one day when random penguins start appearing all over town. Penguins are, after all, cold climate creatures and this is a glorious summer in Southern Japan so even if these are rogue penguins who’ve managed to escape from a zoo, it’s anyone’s guess how they’ve managed to survive. Being the scientifically minded young man he is, Aoyama becomes determined to solve the penguin mystery, especially as it seems to have something to do with the young lady from the dentist’s who he can’t seem to get out of his mind.

Aoyama is, despite his opening gambit, a fairly conceited young man who thinks himself much cleverer than those around him – not only his schoolmates but the adults too (possibly with the exception of the lady from the dentist’s who is after all teaching him how to be better at chess). With an intense superiority complex, Aoyama has few friends (not that that bothers him, particularly) and is often bullied by the class bruiser, Suzuki (Miki Fukui), and his minions, all of which he takes in his stride. He is, however, slightly thrown by the presence of an extremely bright girl in his class, Hamamoto (Megumi Han), who regularly beats him at chess and is interested in black holes among other areas of scientific endeavour Aoyama had earmarked as his own.

Despite suspecting that Hamamoto might be “even more amazing” than he is, Aoyama is not resentful or jealous but remains seemingly oblivious to her attempts to make friends with him. Aoyama, as an intensely “rational” person, is also sometimes insensitive and remains entirely unable to pick up on social cues unlike his more perceptive friend/assitant, Uchida (Rie Kugimiya), who is well aware of the reason Suzuki keeps picking on Hamamoto, but is unable to convey his instinctual understanding of human nature to the logical Aoyama. Armed with this new fragment of information from Uchida, Aoyama uses it in a predictably “rational” fashion by suddenly bringing it up in front of both Hamamoto and Suzuki in “advising” him that liking someone isn’t “embarrassing” and Suzuki should just say what he means rather than making passive aggressive attempts to get attention by being unpleasant. All of which is, ironically enough, quite awkward.

Through carrying out his investigation into the penguin phenomenon, Aoyama is forced to confront his less rational side, eventually affirming that he’ll live his life based on a “personal belief” rather than a scientific principle. Getting a glimpse of the edge of the world and coming to accept that not matter how much fun you’re having there will always come an end, Aoyama decides to live his life in haste anyway running fast towards an inevitable conclusion in the hope of a longed for reconciliation. Sadly, his discoveries don’t seem to have made him any less conceited but he is at least good hearted and eager to help even if he remains determined to walk his “Penguin Highway” all alone while concentrating on becoming a better person. Beautifully animated and tempering its inherent surrealism with gentle whimsy, Penguin Highway is a promising start for Studio Colorido, mixing Ghibli-esque charm with Morimi’s trademark surrealism for a moving coming of age tale in which a rigid young man learns to find the sweet spot between faith and rationality and pledges to live his life in earnest in expectation of its end.

Penguin Highway was screened as part of Fantasia International Film Festival 2018.

Original trailer (no subtitles)

There are two kinds of people in the world, those who swing and those who…don’t – a metaphor which works just as well for baseball and, by implication, facing life’s challenges as it does for music. Shinobu Yaguchi returns after 2001’s

There are two kinds of people in the world, those who swing and those who…don’t – a metaphor which works just as well for baseball and, by implication, facing life’s challenges as it does for music. Shinobu Yaguchi returns after 2001’s  Hideo Gosha had something of a turbulent career, beginning with a series of films about male chivalry and the way that men work out all their personal issues through violence, but owing to the changing nature of cinematic tastes, he found himself at a loose end towards the end of the ‘70s. Things picked up for him in the ‘80s but the altered times brought with them a slightly different approach as Gosha’s films took on an increasingly female focus in which he reflected on how the themes he explored so fully with his male characters might also affect women. In part prompted by his divorce which apparently gave him the view that women were just as capable of deviousness as men are, and by a renewed relationship with his daughter, Gosha overcame the problem of his chanbara stars ageing beyond his demands of them by allowing his actresses to lead.

Hideo Gosha had something of a turbulent career, beginning with a series of films about male chivalry and the way that men work out all their personal issues through violence, but owing to the changing nature of cinematic tastes, he found himself at a loose end towards the end of the ‘70s. Things picked up for him in the ‘80s but the altered times brought with them a slightly different approach as Gosha’s films took on an increasingly female focus in which he reflected on how the themes he explored so fully with his male characters might also affect women. In part prompted by his divorce which apparently gave him the view that women were just as capable of deviousness as men are, and by a renewed relationship with his daughter, Gosha overcame the problem of his chanbara stars ageing beyond his demands of them by allowing his actresses to lead. When Japan does musicals, even Hollywood style musicals, it tends to go for the backstage variety or a kind of hybrid form in which the idol/singing star protagonist gets a few snazzy numbers which somehow blur into the real world. Masayuki Suo’s previous big hit, Shall We Dance, took its title from the classic Rodgers and Hammerstein song featured in the King and I but it’s Lerner and Loewe he turns to for an American style song and dance fiesta relocating My Fair Lady to the world of Kyoto geisha, Lady Maiko (舞妓はレディ, Maiko wa Lady) . My Fair Lady was itself inspired by Shaw’s Pygmalion though replaces much of its class conscious, feminist questioning with genial romance. Suo’s take leans the same way but suffers somewhat in the inefficacy of its half hearted love story seeing as its heroine is only 15 years old.

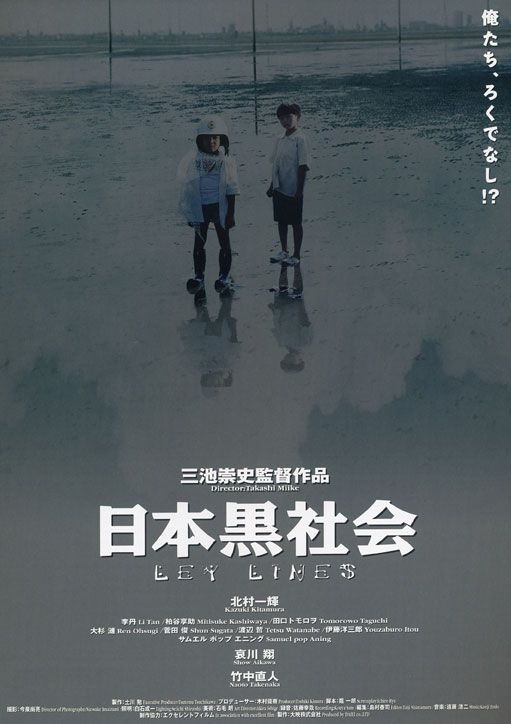

When Japan does musicals, even Hollywood style musicals, it tends to go for the backstage variety or a kind of hybrid form in which the idol/singing star protagonist gets a few snazzy numbers which somehow blur into the real world. Masayuki Suo’s previous big hit, Shall We Dance, took its title from the classic Rodgers and Hammerstein song featured in the King and I but it’s Lerner and Loewe he turns to for an American style song and dance fiesta relocating My Fair Lady to the world of Kyoto geisha, Lady Maiko (舞妓はレディ, Maiko wa Lady) . My Fair Lady was itself inspired by Shaw’s Pygmalion though replaces much of its class conscious, feminist questioning with genial romance. Suo’s take leans the same way but suffers somewhat in the inefficacy of its half hearted love story seeing as its heroine is only 15 years old. The three films loosely banded together under the retrospectively applied title of the Black Society Trilogy are not connected in terms of narrative, characters, tone, or location but they do all reflect on attitudes to foreignness, both of a national and of a spiritual kind. Like Tatsuhito in the first film,

The three films loosely banded together under the retrospectively applied title of the Black Society Trilogy are not connected in terms of narrative, characters, tone, or location but they do all reflect on attitudes to foreignness, both of a national and of a spiritual kind. Like Tatsuhito in the first film,  Hideo Gosha maybe best known for the “manly way” movies of his early career in which angry young men fought for honour and justice, but mostly just to to survive. Late into his career, Gosha decided to change tack for a while with a series of female orientated films either remaining within the familiar gangster genre as in Yakuza Wives, or shifting into world of the red light district as in Tokyo Bordello (吉原炎上, Yoshiwara Enjo). Presumably an attempt to get past the unfamiliarity of the Yoshiwara name, the film’s English title is perhaps a little more obviously salacious than the original Japanese which translates as Yoshiwara Conflagration and directly relates to the real life fire of 1911 in which 300 people were killed and much of the area razed to the ground. Gosha himself grew up not far from the location of the Yoshiwara as it existed in the mid-20th century where it was still a largely lower class area filled with cardsharps, yakuza, and, yes, prostitution (legal in Japan until 1958, outlawed in during the US occupation). The Yoshiwara of the late Meiji era was not so different as the women imprisoned there suffered at the hands of men, exploited by a cruelly misogynistic social system and often driven mad by internalised rage at their continued lack of agency.

Hideo Gosha maybe best known for the “manly way” movies of his early career in which angry young men fought for honour and justice, but mostly just to to survive. Late into his career, Gosha decided to change tack for a while with a series of female orientated films either remaining within the familiar gangster genre as in Yakuza Wives, or shifting into world of the red light district as in Tokyo Bordello (吉原炎上, Yoshiwara Enjo). Presumably an attempt to get past the unfamiliarity of the Yoshiwara name, the film’s English title is perhaps a little more obviously salacious than the original Japanese which translates as Yoshiwara Conflagration and directly relates to the real life fire of 1911 in which 300 people were killed and much of the area razed to the ground. Gosha himself grew up not far from the location of the Yoshiwara as it existed in the mid-20th century where it was still a largely lower class area filled with cardsharps, yakuza, and, yes, prostitution (legal in Japan until 1958, outlawed in during the US occupation). The Yoshiwara of the late Meiji era was not so different as the women imprisoned there suffered at the hands of men, exploited by a cruelly misogynistic social system and often driven mad by internalised rage at their continued lack of agency. Those golden last few summers of high school have provided ample material for countless nostalgia filled Japanese comedies and 700 Days of Battle: Us vs. the Police (ぼくたちと駐在さんの700日戦争, Bokutachi to Chuzai-san no 700 Nichi Senso) is no exception. Set in a small rural town in 1979, this is an innocent story of bored teenagers letting off steam in an age before mass communications ruined everyone’s fun.

Those golden last few summers of high school have provided ample material for countless nostalgia filled Japanese comedies and 700 Days of Battle: Us vs. the Police (ぼくたちと駐在さんの700日戦争, Bokutachi to Chuzai-san no 700 Nichi Senso) is no exception. Set in a small rural town in 1979, this is an innocent story of bored teenagers letting off steam in an age before mass communications ruined everyone’s fun. Considering how well known sumo wrestling is around the world, it’s surprising that it doesn’t make its way onto cinema screens more often. That said, Masayuki Suo’s Sumo Do, Sumo Don’t (シコふんじゃった, Shiko Funjatta) displays an ambivalent attitude to this ancient sport in that it’s definitely uncool, ridiculous, and prone to the obsessive fan effect, yet it’s also noble – not only a game of size and brute force but of strategy and comradeship. Not unlike Suo’s later film for which he remains most well known, Shall We Dance, Sumo Do, Sumo Don’t uses the presumed unpopularity of its central activity as a magnet which draws in and then binds together a disparate, originally reluctant collection of central characters.

Considering how well known sumo wrestling is around the world, it’s surprising that it doesn’t make its way onto cinema screens more often. That said, Masayuki Suo’s Sumo Do, Sumo Don’t (シコふんじゃった, Shiko Funjatta) displays an ambivalent attitude to this ancient sport in that it’s definitely uncool, ridiculous, and prone to the obsessive fan effect, yet it’s also noble – not only a game of size and brute force but of strategy and comradeship. Not unlike Suo’s later film for which he remains most well known, Shall We Dance, Sumo Do, Sumo Don’t uses the presumed unpopularity of its central activity as a magnet which draws in and then binds together a disparate, originally reluctant collection of central characters.