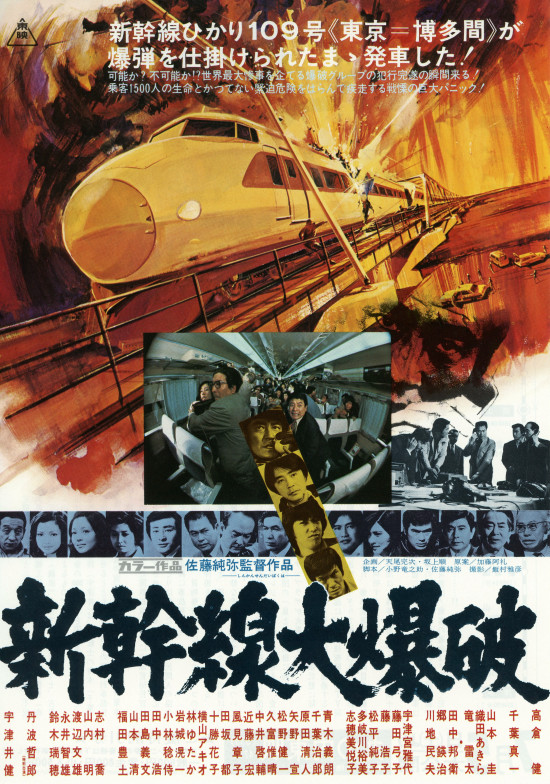

For one reason or another, the 1970s gave rise to a wave of disaster movies as Earthquakes devastated cities, high rise buildings caught fire, and ocean liners capsized. Japan wanted in on the action and so set about constructing its own culturally specific crisis movie. The central idea behind The Bullet Train (新幹線大爆破, Shinkansen Daibakuha) may well sound familiar as it was reappropriated for the 1994 smash hit and ongoing pop culture phenomenon Speed, but even if de Bont’s finely tuned rollercoaster was not exactly devoid of subversive political commentary The Bullet Train takes things one step further.

For one reason or another, the 1970s gave rise to a wave of disaster movies as Earthquakes devastated cities, high rise buildings caught fire, and ocean liners capsized. Japan wanted in on the action and so set about constructing its own culturally specific crisis movie. The central idea behind The Bullet Train (新幹線大爆破, Shinkansen Daibakuha) may well sound familiar as it was reappropriated for the 1994 smash hit and ongoing pop culture phenomenon Speed, but even if de Bont’s finely tuned rollercoaster was not exactly devoid of subversive political commentary The Bullet Train takes things one step further.

A bomb threat has been issued for bullet train Hikari 109. This is not a unique occurrence – it happens often enough for there to be a procedure to be followed, but this time is different. So that the authorities don’t simply stop the train to find the device as normal, it’s been attached to a speedometer which will trigger the bomb if the train slows below 80mph. A second bomb has been placed on a freight train to encourage the authorities to believe the bullet train device is real and when it does indeed go off, no one quite knows what to do.

The immediate response to this kind of crisis is placation – the train company does not have the money to pay a ransom, but assures the bomber that they will try and get the money from the government. Somewhat unusually, the bomber is played by the film’s biggest star, Ken Takakura, and is a broadly sympathetic figure despite the heinous crime which he is in the middle of perpetrating.

The bullet train is not just a super fast method of mass transportation but a concise symbol of post-war Japan’s path to economic prosperity. fetching up in the 1960s as the nation began to cast off the lingering traces of its wartime defeat and return to the world stage as the host of the 1964 olympics, the bullet train network allowed Japan to ride its own rails into the future. All of this economic prosperity, however, was not evenly distributed. Where large corporations expanded, the small businessman was squeezed, manufacturing suffered, and the little guy felt himself left out of the paradise promised by a seeming economic miracle.

Thus our three bombers are all members of this disenfranchised class, disillusioned with a cruel society and taking aim squarely at the symbol of their oppression. Takakura’s Okita is not so much a mad bomber as a man pushed past breaking point by repeated betrayals as his factory went under leading him to drink and thereby to the breakdown of his marriage. He recruits two helpers – a young boy who came to the city from the countryside as one of the many young men promised good employment building the modern Tokyo but found only lies and exploitation, and the other an embittered former student protestor, angry and disillusioned with his fellow revolutionaries and the eventual subversion of their failed revolution.

Their aim is not to destroy the bullet train for any political reason, but force the government to compensate them for failing to redistribute the economic boon to all areas of society. Okita seems to have little regard for the train’s passengers, perhaps considering them merely collateral damage or willing accomplices in his oppression. Figuring out that something is wrong with the train due to its slower speed and failure to stop at the first station the passengers become restless giving rise to hilarious scenes of salarymen panicking about missed meetings and offering vast bribes to try and push their way to the front of the onboard phone queue, but when a heavily pregnant woman becomes distressed the consequences are far more severe.

Left alone to manage the situation by himself, the put upon controller does his best to keep everyone calm but becomes increasingly frustrated by the inhumane actions of the authorities from his bosses at the train company to the police and government. Always with one eye on the media, the train company is more preoccupied with being seen to have passenger safety at heart rather than actually safeguarding it. The irony is that the automatic breaking system poses a serious threat now that speed is of the essence but when the decision is made to simply ignore a second bomb threat it’s easy to see where the priorities lie for those at the top of the corporate ladder.

Okita and his gang are underdog everymen striking back against increasing economic inequality but given that their plan endangers the lives of 1500 people, casting them as heroes is extremely uncomfortable. Sato keeps the tension high despite switching between the three different plot strands as Okita plots his next move while the train company and police plot theirs even if he can’t sustain the mammoth 2.5hr running time. A strange mix of genres from the original disaster movie to broad satire and angry revolt against corrupt authority, The Bullet Train is an oddly rich experience even if it never quite reaches its final destination.

Original trailer (no subtitles)

After such a long and successful career, Yoji Yamada has perhaps earned the right to a little retrospection. Offering a smattering of cinematic throwbacks in homages to both Yasujiro Ozu and Kon Ichikawa, Yamada then turned his attention to the years of militarism and warfare in the tales of a struggling mother,

After such a long and successful career, Yoji Yamada has perhaps earned the right to a little retrospection. Offering a smattering of cinematic throwbacks in homages to both Yasujiro Ozu and Kon Ichikawa, Yamada then turned his attention to the years of militarism and warfare in the tales of a struggling mother,  Hideo Gosha maybe best known for the “manly way” movies of his early career in which angry young men fought for honour and justice, but mostly just to to survive. Late into his career, Gosha decided to change tack for a while with a series of female orientated films either remaining within the familiar gangster genre as in Yakuza Wives, or shifting into world of the red light district as in Tokyo Bordello (吉原炎上, Yoshiwara Enjo). Presumably an attempt to get past the unfamiliarity of the Yoshiwara name, the film’s English title is perhaps a little more obviously salacious than the original Japanese which translates as Yoshiwara Conflagration and directly relates to the real life fire of 1911 in which 300 people were killed and much of the area razed to the ground. Gosha himself grew up not far from the location of the Yoshiwara as it existed in the mid-20th century where it was still a largely lower class area filled with cardsharps, yakuza, and, yes, prostitution (legal in Japan until 1958, outlawed in during the US occupation). The Yoshiwara of the late Meiji era was not so different as the women imprisoned there suffered at the hands of men, exploited by a cruelly misogynistic social system and often driven mad by internalised rage at their continued lack of agency.

Hideo Gosha maybe best known for the “manly way” movies of his early career in which angry young men fought for honour and justice, but mostly just to to survive. Late into his career, Gosha decided to change tack for a while with a series of female orientated films either remaining within the familiar gangster genre as in Yakuza Wives, or shifting into world of the red light district as in Tokyo Bordello (吉原炎上, Yoshiwara Enjo). Presumably an attempt to get past the unfamiliarity of the Yoshiwara name, the film’s English title is perhaps a little more obviously salacious than the original Japanese which translates as Yoshiwara Conflagration and directly relates to the real life fire of 1911 in which 300 people were killed and much of the area razed to the ground. Gosha himself grew up not far from the location of the Yoshiwara as it existed in the mid-20th century where it was still a largely lower class area filled with cardsharps, yakuza, and, yes, prostitution (legal in Japan until 1958, outlawed in during the US occupation). The Yoshiwara of the late Meiji era was not so different as the women imprisoned there suffered at the hands of men, exploited by a cruelly misogynistic social system and often driven mad by internalised rage at their continued lack of agency.

If there is a frequent criticism directed at the always bankable director Yoji Yamada, it’s that his approach is one which continues to value the past over the future. Recent years have seen him looking back, literally, in terms of both themes and style with remakes of films by two Japanese masters – Ozu in his Tokyo Story homage Tokyo Family, and Kon Ichikawa in Her Brother. While he chose to update both of those pieces for the modern day, 2008’s

If there is a frequent criticism directed at the always bankable director Yoji Yamada, it’s that his approach is one which continues to value the past over the future. Recent years have seen him looking back, literally, in terms of both themes and style with remakes of films by two Japanese masters – Ozu in his Tokyo Story homage Tokyo Family, and Kon Ichikawa in Her Brother. While he chose to update both of those pieces for the modern day, 2008’s  Prolific as he is, veteran director Yoji Yamada (or perhaps his frequent screenwriter in recent years Emiko Hiramatsu) clearly takes pleasure in selecting film titles but What a Wonderful Family! (家族はつらいよ, Kazoku wa Tsurai yo) takes things one step further by referencing Yamada’s own long running film series Otoko wa Tsurai yo (better known as Tora-san). Stepping back into the realms of comedy, Yamada brings a little of that Tora-san warmth with him for a wry look at the contemporary Japanese family with all of its classic and universal aspects both good and bad even as it finds itself undergoing number of social changes.

Prolific as he is, veteran director Yoji Yamada (or perhaps his frequent screenwriter in recent years Emiko Hiramatsu) clearly takes pleasure in selecting film titles but What a Wonderful Family! (家族はつらいよ, Kazoku wa Tsurai yo) takes things one step further by referencing Yamada’s own long running film series Otoko wa Tsurai yo (better known as Tora-san). Stepping back into the realms of comedy, Yamada brings a little of that Tora-san warmth with him for a wry look at the contemporary Japanese family with all of its classic and universal aspects both good and bad even as it finds itself undergoing number of social changes. The ‘70s. It was a bleak time when everyone was frightened of everything and desperately needed to be reminded why everything was so terrifying by sitting in a dark room and watching a disaster unfold on-screen. Thank goodness everything is so different now! Being the extraordinarily savvy guy he was, Hiroki Kadokawa decided he could harness this wave of cold war paranoia to make his move into international cinema with the still fledgling film arm he’d added to the publishing company inherited from his father.

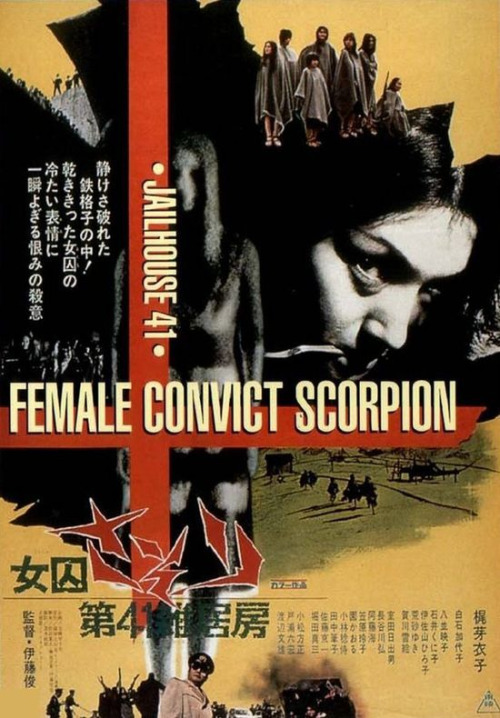

The ‘70s. It was a bleak time when everyone was frightened of everything and desperately needed to be reminded why everything was so terrifying by sitting in a dark room and watching a disaster unfold on-screen. Thank goodness everything is so different now! Being the extraordinarily savvy guy he was, Hiroki Kadokawa decided he could harness this wave of cold war paranoia to make his move into international cinema with the still fledgling film arm he’d added to the publishing company inherited from his father. Female Prisoner Scorpion: Jailhouse 41 (女囚さそり第41雑居房, Joshu Sasori – Dai 41 Zakkyobo) picks up around a year after the end of

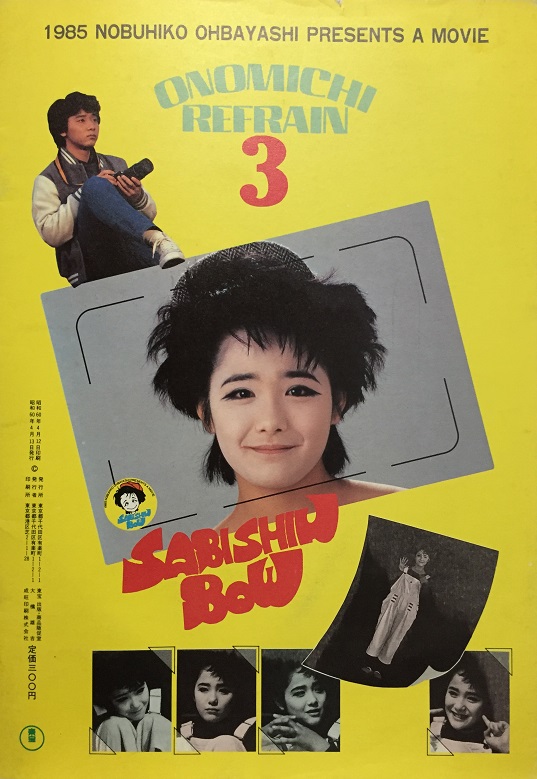

Female Prisoner Scorpion: Jailhouse 41 (女囚さそり第41雑居房, Joshu Sasori – Dai 41 Zakkyobo) picks up around a year after the end of  Miss Lonely (さびしんぼう, Sabishinbou, AKA Lonelyheart) is the final film in Obayashi’s Onomichi Trilogy all of which are set in his own hometown of Onomichi. This time Obayashi casts up and coming idol of the time, Yasuko Tomita, in a dual role of a reserved high school student and a mysterious spirit known as Miss Lonely. In typical idol film fashion, Tomita also sings the theme tune though this is a much more male lead effort than many an idol themed teen movie.

Miss Lonely (さびしんぼう, Sabishinbou, AKA Lonelyheart) is the final film in Obayashi’s Onomichi Trilogy all of which are set in his own hometown of Onomichi. This time Obayashi casts up and coming idol of the time, Yasuko Tomita, in a dual role of a reserved high school student and a mysterious spirit known as Miss Lonely. In typical idol film fashion, Tomita also sings the theme tune though this is a much more male lead effort than many an idol themed teen movie. Yoji Yamada’s films have an almost Pavlovian effect in that they send even the most hard hearted of viewers out for tissues even before the title screen has landed. Kabei (母べえ), based on the real life memoirs of script supervisor and frequent Kurosawa collaborator Teruyo Nogami, is a scathing indictment of war, militarism and the madness of nationalist fervour masquerading as a “hahamono”. As such it is engineered to break the hearts of the world, both in its tale of a self sacrificing mother slowly losing everything through no fault of her own but still doing her best for her daughters, and in the crushing inevitably of its ever increasing tragedy.

Yoji Yamada’s films have an almost Pavlovian effect in that they send even the most hard hearted of viewers out for tissues even before the title screen has landed. Kabei (母べえ), based on the real life memoirs of script supervisor and frequent Kurosawa collaborator Teruyo Nogami, is a scathing indictment of war, militarism and the madness of nationalist fervour masquerading as a “hahamono”. As such it is engineered to break the hearts of the world, both in its tale of a self sacrificing mother slowly losing everything through no fault of her own but still doing her best for her daughters, and in the crushing inevitably of its ever increasing tragedy. Like many directors during the 1980s, Nobuhiko Obayashi was unable to resist the lure of a Kadokawa teen movie but His Motorbike, Her Island (彼のオートバイ彼女の島, Kare no Ootobai, Kanojo no Shima) is a typically strange 1950s throwback with its tale of motorcycle loving youngsters and their ennui filled days. Switching between black and white and colour, Obayashi paints a picture of a young man trapped in an eternal summer from which he has no desire to escape.

Like many directors during the 1980s, Nobuhiko Obayashi was unable to resist the lure of a Kadokawa teen movie but His Motorbike, Her Island (彼のオートバイ彼女の島, Kare no Ootobai, Kanojo no Shima) is a typically strange 1950s throwback with its tale of motorcycle loving youngsters and their ennui filled days. Switching between black and white and colour, Obayashi paints a picture of a young man trapped in an eternal summer from which he has no desire to escape.