A man struggles with conflicted emotions after learning that his teenage son has killed his mother and sister in a bloody attack in Philip Yung Chi-kwong’s empathic character drama, Papa (爸爸). As much as he’s responsible for the deaths of those dearest to him, Ming (Dylan So) is still Nin’s (Sean Lau Ching-wan) son and he has a real desire to love and care for him while at the same time wondering why and continuing to blame himself as if this tragedy were really provoked by his failures as a father.

Weaving back and forth through the last 30 years, Yung meditates on a theme of loss while linking Nin’s life with key moments in history. In 1997, the year of Hong Kong’s handover to China and also the beginning of the Asian financial crisis, Nin buys a newfangled digital camera hoping to record the birth of his daughter, Grace. Nin isn’t convinced by this technological advance and wonders if it will just lead to people wasting their time taking endless photos now they don’t have to worry about running out of film, but it’s also the means by which he is eventually able to preserve his family by making use of the temporary pause provided by its timer function so that they can all occupy the same space for a moment but also for eternity.

Otherwise, he worries that the family’s business concerns put too much strain on their relationships. He and his wife Yin (Jo Koo Cho-lam) worked opposing shifts at a 24hr eatery meaning they rarely got to spend time together and the children grew up with each of their parents never fully there. Though Nin had wanted to stop opening overnight so they could have a more conventional family life, Yin, from Guangdong on the Mainland, was against it and wanted to keep going until the children were a bit older. There’s an implication that this 24hr culture is also something of an older Hong Kong that’s gradually being erased in the post-Handover society and that Nin and his family are living in an age of decline.

Though Ming won’t give a reason for what he did, in his court testimony he claims to have heard voices telling him that there were too many people and it was making everyone angry so he needed to kill a few and bring the population down. Nin again blames himself, reflecting that the family live in a typically cramped flat where the children have to share a room and everyone is piled on top of each other even if he and his wife are rarely there at the same time. In flashbacks to happier times when Ming was small, there’s a suggestion that Ming resented his sister and that he always had to share not only his possessions, his mother suggesting that they buy a smaller bike for his birthday so Grace can use it too, but his parents’ attention. In a particularly cruel moment, Ming tells Grace that none of her favourite characters from Doraemon are actually “real” but merely imaginary friends Nobita made up in his head because he is autistic.

But along with his aloofness, poor social skills and lack of empathy, Nin remembers Ming caring for the stray kitten Grace adopted but then grew tired of though he had not originally been in favour of taking it in. He seems to have been living with undiagnosed schizophrenia, something else Nin blames himself for wondering if there was something he could have done. “If I’d been there it wouldn’t have happened,” he tells the press in the incident’s aftermath, but even if he was ill it’s hard to believe the little boy he taught to ride a bike and took on trips to the beach could have done something so violent and hateful and then show such little remorse. Even so, he’s still his son and the only thing he can still rescue from the wreckage of his life while meditating on all he’s lost. As such, it’s another recent film from Hong Kong about how to live on in a ruined world. Yung’s camera has an elegiac quality aided by a retro synth score and the neon lighting of an older Hong Kong drenched in melancholy, but also weary resignation and a determination to keep going if only in memory of a long absent past that were it not for a photograph “to prove that we were here” would go unremembered.

Trailer (Traditional Chinese / English subtitles)

Sean Lau Ching-wan and Nicholas Tse are together again after being denied the opportunity to reteam for a sequel to the acclaimed

Sean Lau Ching-wan and Nicholas Tse are together again after being denied the opportunity to reteam for a sequel to the acclaimed

When

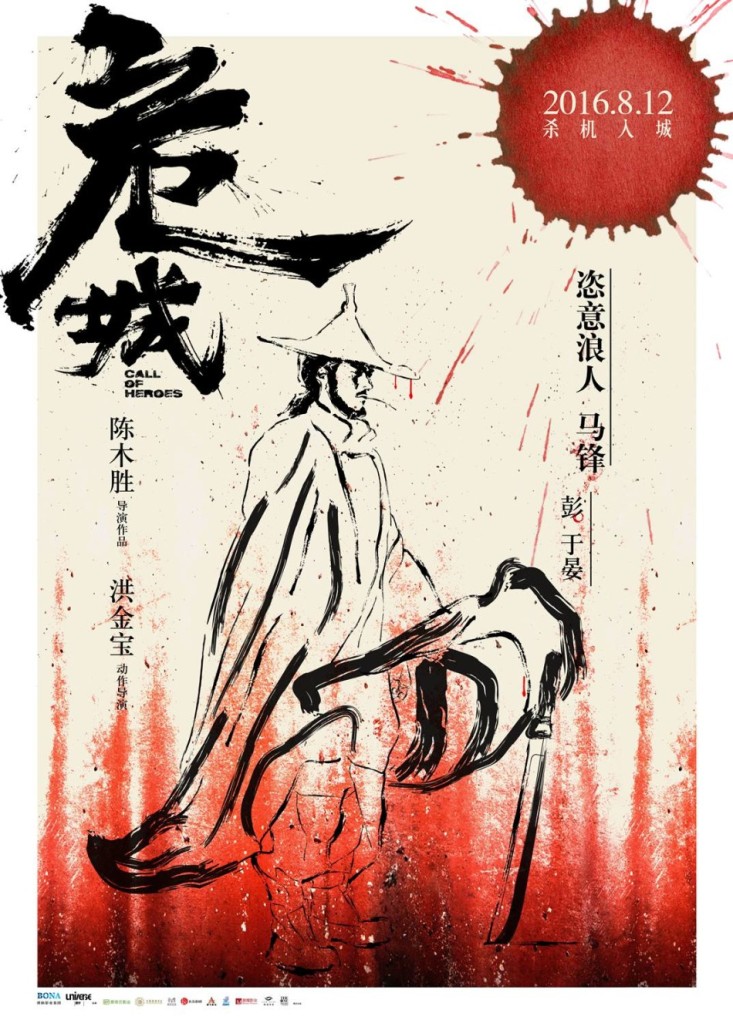

When  A blast from the past in more ways than one, Benny Chan’s Call of Heroes (危城, Wēi Chéng) is a western in disguise though one filtered through Akira Kurosawa and Sergio Leone more than John Ford. Filled with Morricone-esque musical riffs and poncho wearing reluctant heroes, Chan’s bounce back to the post-revolutionary warlord era is one pregnant with contemporary echoes yet totally unafraid to add a touch of uncinematic darkness to its wisecracking world.

A blast from the past in more ways than one, Benny Chan’s Call of Heroes (危城, Wēi Chéng) is a western in disguise though one filtered through Akira Kurosawa and Sergio Leone more than John Ford. Filled with Morricone-esque musical riffs and poncho wearing reluctant heroes, Chan’s bounce back to the post-revolutionary warlord era is one pregnant with contemporary echoes yet totally unafraid to add a touch of uncinematic darkness to its wisecracking world.