Perhaps in some ways out of step with the times, the 2017 Nippon TV drama Caution, Hazardous Wife (奥様は、取り扱い注意, Okusama wa, Toriatsukai Chui), like the earlier Secret Agent Erika, saw top assassin Nami (Haruka Ayase) fake her own death in order to live a “normal” life as an “ordinary housewife” married to “boring salaryman” Yuki (Hidetoshi Nishijima). Nami could not however resist using her skills for good and bravely took on a local yakuza gang who’d been running a suburban prostitution ring through employing handsome gigolos to seduce emotionally neglected housewives and thereafter blackmailing them into sex work. The series ended on a cliffhanger in which, spoiler alert, Nami was confronted by her husband who turned out to be a Public Security Bureau officer originally tasked with monitoring her before genuinely falling in love.

This brief background recap is useful but not strictly necessary in approaching the series’ big screen incarnation, Caution, Hazardous Wife: The Movie, which ironically assumes the audience knows Nami’s secret backstory but also obfuscates it in picking up 18 months after the cliffhanger to find her now living as “Kumi” in a tranquil seaside town having apparently lost her memory. The town will not remain tranquil for long, however, as a mayoral race is about to bring tensions to the fore in the polarising issue of a prospective methane hydrate plant the authorities insist is necessary to revive the area’s moribund economy while others worry about industrial pollution and its effects on the local sea life. Unsurprisingly, the events will turn out to have a connection to Nami’s past while she struggles to regain her lost memories and preserve the peaceful, ordinary life with her husband which is all she’s ever really wanted.

Though some might find it somewhat conservative that what Nami wants is to become a conventional housewife, what she’s looking for is the stability of the “normal” life she’s never known. As such, she may not actually want to regain her memories, preferring to go on living as Kumi who has perfected the housewife skills which so eluded Nami including becoming a top cook, for as long as possible. Yuki, meanwhile, now living as high school teacher Yuji, feels something similar having been ordered to “deal with” his wife if she remembers who she is but refuses to become a PSB asset.

Upping production values from the TV drama, Sato keeps Nami in the dark for as long as possible though her sense of social responsibility remains just as strong as she bravely intervenes when coming across a gang of teens taunting a boy with homophobic slurs for having a pink coin curse, later becoming concerned on witnessing the leader of the opposition to the plant being attacked by thugs in an attempt to intimidate him out of his decision to stand as a rival candidate to the incumbent mayor. Nevertheless, he allows space for plenty of dramatic action scenes including flashbacks to Nami’s career as an international assassin while the final set piece also throws in some bickering marital comedy before turning unexpectedly dark.

Regaining her memories, Nami’s inner conflict is in her complicated relationship with Yuki wondering if he ever really loved the “real” her or if he perhaps preferred Kumi the docile Stepford wife, which is ironically the cover identity she’d longed to construct. Conflicted and suspecting his wife may have remembered who she really is, Yuki tells her to forget about the past but also that his feelings won’t change and she should be free to be herself but as Nami later realises the past won’t let her go and the peaceful life she’d dreamed of might be harder to preserve than she’d previously thought even as she commits herself to embracing the life she has now because her relationship with Yuki is the most important thing to her despite her lingering doubt.

Touching on a few hot button issues from industrial pollution and environmental concerns to economic decline and rural depopulation, Sato nevertheless returns to the outlandish absurdity of the TV drama as Nami finds herself facing off against Russian gangsters while exposing a plot by shady conglomerates to exploit a small-town desire for better access to jobs and infrastructure, along with judicial corruption and electoral interference. Nevertheless, the hometown spirit eventually wins out even if Nami finds herself on the run once again though having gained a little more emotional clarity.

Caution, Hazardous Wife: The Movie streamed as part of this year’s Fantasia International Film Festival. The original TV series is also available to stream with English subtitles (along with those in several other languages) in many territories via Viki.

International trailer (English subtitles)

Parks are a common feature of modern city life – a stretch of green among the grey, but it’s important to remember that there has not always been such beautiful shared space set aside for public use. Natsuki Seta’s light and breezy youth comedy, Parks (PARKS パークス), was commissioned in celebration of the centenary of the Tokyo park where the majority of the action takes place, Inokashira. Mixing early Godardian whimsy with new wave voice over and the kind of innocent adventure not seen since the Kadokawa idol days, Parks is a sometimes melancholy, wistful tribute to a place where chance meetings can define lifetimes as well as to brief yet memorable summers spent with gone but not forgotten friends doing something which seems important but which in retrospect may be trivial.

Parks are a common feature of modern city life – a stretch of green among the grey, but it’s important to remember that there has not always been such beautiful shared space set aside for public use. Natsuki Seta’s light and breezy youth comedy, Parks (PARKS パークス), was commissioned in celebration of the centenary of the Tokyo park where the majority of the action takes place, Inokashira. Mixing early Godardian whimsy with new wave voice over and the kind of innocent adventure not seen since the Kadokawa idol days, Parks is a sometimes melancholy, wistful tribute to a place where chance meetings can define lifetimes as well as to brief yet memorable summers spent with gone but not forgotten friends doing something which seems important but which in retrospect may be trivial. Summer Holiday Everyday – It’s certainly an upbeat way to describe unemployment but then everything is improbably upbeat and cheerful in the always sunny world of Shusuke Kaneko’s adaptation of Yumiko Oshima’s shoujo manga. Published in the mid-bubble era of 1988, Oshima’s world is one in which anything is possible but by the time of the live action movie release in 1994 perhaps this was not so much the case. Nevertheless, Kaneko’s film retains the happy-go-lucky tone and offers note of celebration for the unconventional as a path to success and individual happiness.

Summer Holiday Everyday – It’s certainly an upbeat way to describe unemployment but then everything is improbably upbeat and cheerful in the always sunny world of Shusuke Kaneko’s adaptation of Yumiko Oshima’s shoujo manga. Published in the mid-bubble era of 1988, Oshima’s world is one in which anything is possible but by the time of the live action movie release in 1994 perhaps this was not so much the case. Nevertheless, Kaneko’s film retains the happy-go-lucky tone and offers note of celebration for the unconventional as a path to success and individual happiness.

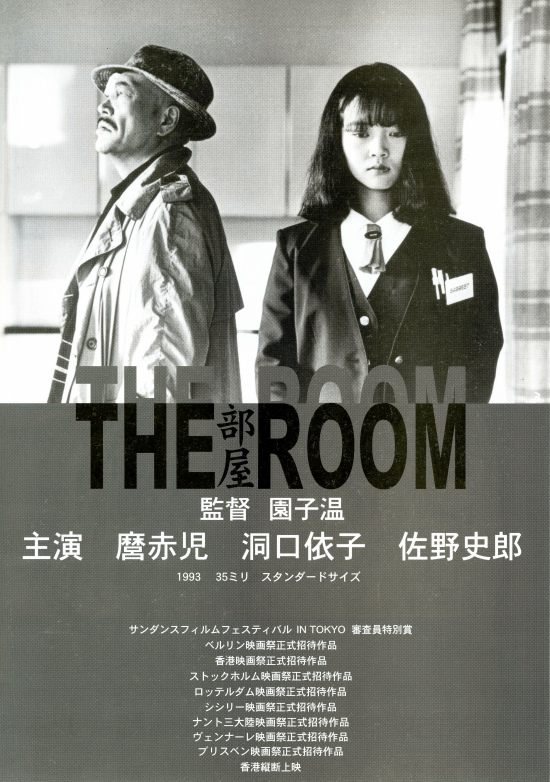

Though the later work of Sion Sono is often noted for its cinematic excess, his earlier career saw him embracing the art of minimalism. The Room (部屋, Heya) finds him in the realms of existentialist noir as a grumpy hitman whiles away his remaining time in the search for the perfect apartment guided only by a detached estate agent.

Though the later work of Sion Sono is often noted for its cinematic excess, his earlier career saw him embracing the art of minimalism. The Room (部屋, Heya) finds him in the realms of existentialist noir as a grumpy hitman whiles away his remaining time in the search for the perfect apartment guided only by a detached estate agent. Every once in a while an artist emerges whose work is so far ahead of its time that the audience of the day is unwilling to accept but generations to come will finally recognise for the achievement it represents. So it is for Sharaku – a young man whose abilities and ambitions are ruthlessly manipulated by those around him for their own gain. Brought to the screen by veteran new wave director Masahiro Shinoda, Sharaku (写楽) is an attempt to throw some light on the life of this mysterious historical figure who comes to symbolise, in many ways, the turbulence of his era.

Every once in a while an artist emerges whose work is so far ahead of its time that the audience of the day is unwilling to accept but generations to come will finally recognise for the achievement it represents. So it is for Sharaku – a young man whose abilities and ambitions are ruthlessly manipulated by those around him for their own gain. Brought to the screen by veteran new wave director Masahiro Shinoda, Sharaku (写楽) is an attempt to throw some light on the life of this mysterious historical figure who comes to symbolise, in many ways, the turbulence of his era.