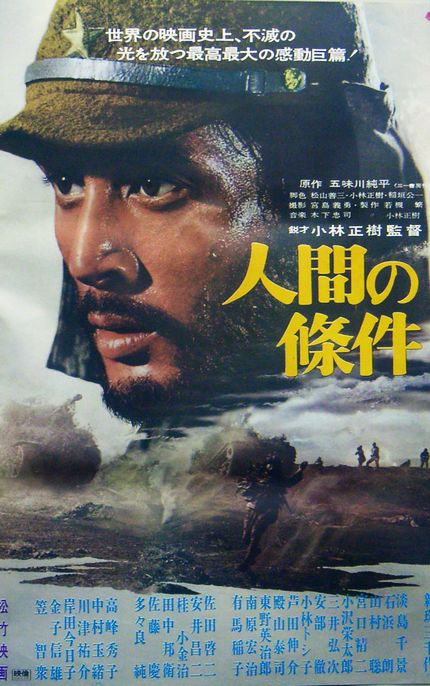

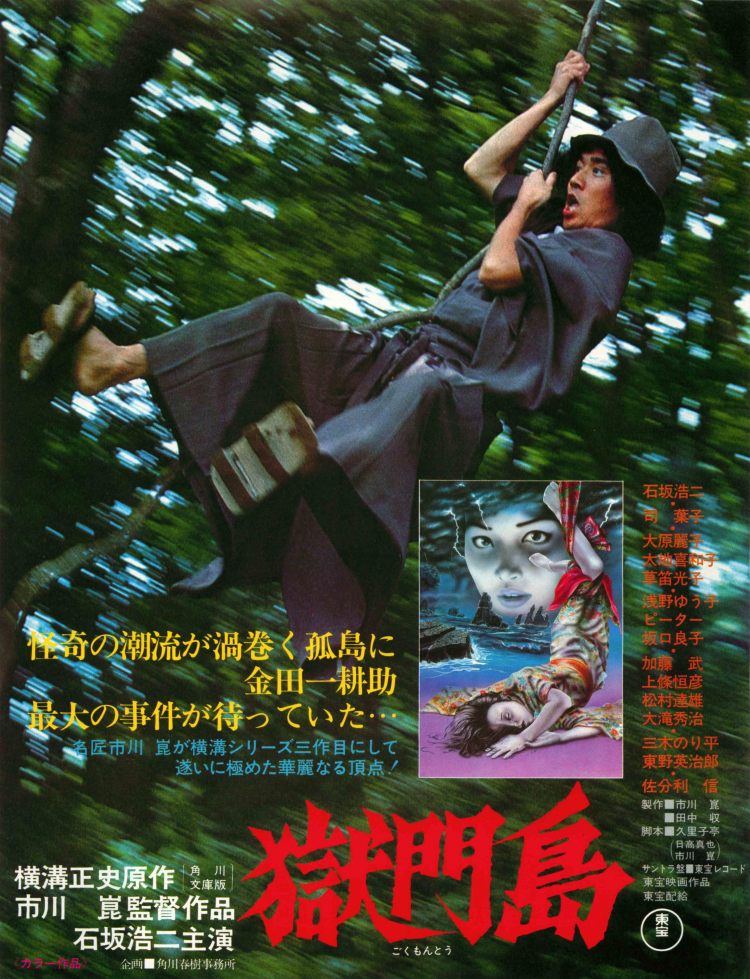

Kon Ichikawa revisits the world of Kosuke Kindaichi for the third time in Devil’s Island (獄門島, Gokumon-to). Confusingly enough, Devil’s Island is adapted from the second novel in the Kidaichi series and set a few years before Ichikawa’s previous adaptation The Devil’s Ballad (the twin devils are just a coincidence). As with his other Kindaichi adaptations, Ichikawa retains the immediate post-war setting of the novel though this time the war is both fore and background as our tale is set on profane soil, a pirate island once home to Japan’s most heinous exiled criminals, which is to say it is the literal fount of every social failing which has informed the last 20 years of turbulent militarist history.

Kon Ichikawa revisits the world of Kosuke Kindaichi for the third time in Devil’s Island (獄門島, Gokumon-to). Confusingly enough, Devil’s Island is adapted from the second novel in the Kidaichi series and set a few years before Ichikawa’s previous adaptation The Devil’s Ballad (the twin devils are just a coincidence). As with his other Kindaichi adaptations, Ichikawa retains the immediate post-war setting of the novel though this time the war is both fore and background as our tale is set on profane soil, a pirate island once home to Japan’s most heinous exiled criminals, which is to say it is the literal fount of every social failing which has informed the last 20 years of turbulent militarist history.

In 1946, Kindaichi (Koji Ishizaka) travels to Kasaoka to catch the ferry to the island. On the way he runs into a demobbed soldier hobbling along on crutches only to catch sight of the man quickly picking his up crutches and running across the railway tracks when he thought no one was looking. Kindaichi is in luck – before he even reaches the boat he runs into the very man he’s come to see, Reverend Ryonen (Shin Saburi), for whom he has a message. Posing as a fellow soldier, Kindaichi reveals he has a “last letter” from a man named Chimata who sadly passed away right after the cessation of hostilities having contracted malaria. Chimata, as we later find out, was the legitimate heir of the island’s most prominent family. Kindaichi chooses not to reveal his true purpose, but the truth is that Chimata suspected his death would put his three younger sisters in danger from various unscrupulous family members attempting to subvert the succession.

Your average Japanese mystery is not, as it turns out, so far from Agatha Christie as one might assume and this is very much a tale of petty class concerns, island mores, and changing social conventions. The extremely confusing island hierarchy starts with the head of household who doubles as the head of the local fishing union and then shuffles out to the branch line and brassy sister-in-law Tomoe (Kiwako Taichi) who is keen claim all the authority she is entitled to. The old patriarch, Yosamatsu (Taketoshi Naito), went quite mad at the beginning of the war and is kept in a bamboo cage in the family compound where he screams and rails, only calmed by the gentle voice of Sanae (Reiko Ohara), a poor relation raised in the main house alongside her brother Hitoshi who hasn’t yet returned from the war. Aside from Yosamatsu, the absence of the two young men means the main house is now entirely inhabited by women, looked after by veteran maid Katsuno (Yoko Tsukasa).

Then again, Japanese mysteries hinge on riddles more than they depend on motives and there are certainly plenty of those on this weird little island where they don’t like “outsiders”. Ichikawa hints at the central conceit by flashing up haiku directly on the screen along with a few original chapter headings for Kindaichi whose eccentricities might seem less noticeable in such an obviously crazy place but strangely seem all the more overt, his trademark dandruff falling like rain from his tousled hair. It has to be said that Kindaichi fails in his otherwise pure hearted aims – he doesn’t make a great deal of effort to “save” the sisters and only attempts to solve the crimes as they occur, each one informing the next. This time around he gets trouble from both irritatingly bumbling detective Todoroki (Takeshi Kato) and his assistant Bando (Kazunaga Tsuji) , and the local bobby who immediately locks Kindaichi up and declares the crimes solved on the grounds that they only started happening after Kindaichi arrived.

Meanwhile, there are rumours of an escaped “pirate” running loose, demobbed soldiers, and a host of dark local customs contrasting strongly with the idyllic scenery and the strange “pureness” of this remote island otherwise untouched by the war’s folly save for the immediate events entirely precipitated by the absence of two young men taken away to die on foreign shores. Though the various motives for the crimes are older – shame, greed, classism, a bizarre dispute between Buddhists and Shamans, none of this would have been happening if the war hadn’t stuck its nose into island business and unbalanced the complex local hierarchy. Tragically, the crimes themselves all come to nought as a late arriving piece of news renders them null and void. Just when you think you’ve won, the rug is pulled from under you and the war wins again. Ichikawa opts for a for a defiantly straightforward style but adopts a few interesting editing techniques including fast cutting to insert tiny flashbacks as our various suspects suddenly remember a few “relevant” details. This strange island, imbued with ancient evils carried from the mainland, finds itself not quite as immune from national struggles as it once thought though perhaps manages to right itself through finally admitting the truth and acknowledging the sheer lunacy that led to the sorry events in which it has recently become embroiled.

Original trailer (no subtitles)

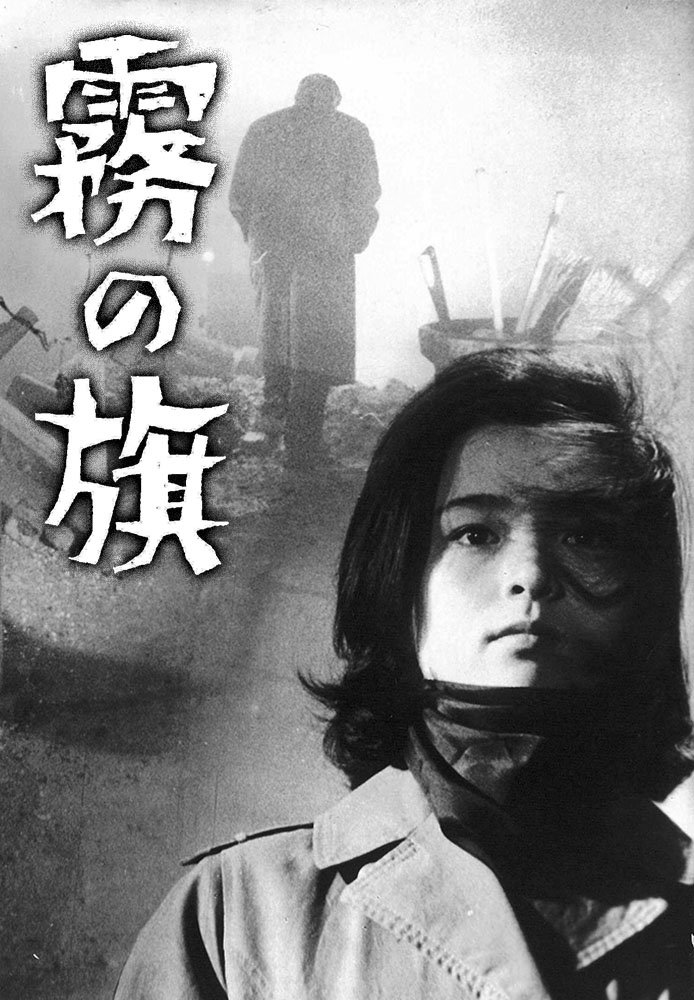

In theory, we’re all equal under the law, but the business of justice is anything but egalitarian. Yoji Yamada is generally known for his tearjerking melodramas or genial comedies but Flag in the Mist (霧の旗, Kiri no Hata) is a rare step away from his most representative genres, drawing inspiration from America film noir and adding a touch of typically Japanese cynical humour. Based on a novel by Japanese mystery master Seicho Matsumoto, Flag in the Mist is a tale of hopeless, mutually destructive revenge which sees a murderer walk free while the honest but selfish pay dearly for daring to ignore the poor in need of help. A powerful message in the increasing economic prosperity of 1965, but one that leaves no clear path for the successful revenger.

In theory, we’re all equal under the law, but the business of justice is anything but egalitarian. Yoji Yamada is generally known for his tearjerking melodramas or genial comedies but Flag in the Mist (霧の旗, Kiri no Hata) is a rare step away from his most representative genres, drawing inspiration from America film noir and adding a touch of typically Japanese cynical humour. Based on a novel by Japanese mystery master Seicho Matsumoto, Flag in the Mist is a tale of hopeless, mutually destructive revenge which sees a murderer walk free while the honest but selfish pay dearly for daring to ignore the poor in need of help. A powerful message in the increasing economic prosperity of 1965, but one that leaves no clear path for the successful revenger. Ogami (Tomisaburo Wakayama), former Shogun executioner now a fugitive in search of justice after being framed for treason by the villainous Yagyu clan who are also responsible for the death of his wife, is still on the Demon’s Way with his young son Daigoro (Akihiro Tomikawa). Five films into this six film cycle, the pair are edging closer to their goal as the evil Lord Retsudo continues to make shadowy appearances at the corners of their world. However, the Demon’s Way carries a heavy toll, littered with corpses of unlucky challengers, the road has, of late, begun to claim the lives of the virtuous along with the venal. Conflicted as he was in his execution of a contract to assassinate the tragic Oyuki in the previous instalment,

Ogami (Tomisaburo Wakayama), former Shogun executioner now a fugitive in search of justice after being framed for treason by the villainous Yagyu clan who are also responsible for the death of his wife, is still on the Demon’s Way with his young son Daigoro (Akihiro Tomikawa). Five films into this six film cycle, the pair are edging closer to their goal as the evil Lord Retsudo continues to make shadowy appearances at the corners of their world. However, the Demon’s Way carries a heavy toll, littered with corpses of unlucky challengers, the road has, of late, begun to claim the lives of the virtuous along with the venal. Conflicted as he was in his execution of a contract to assassinate the tragic Oyuki in the previous instalment,  When it comes to period exploitation films of the 1970s, one name looms large – Kazuo Koike. A prolific mangaka, Koike also moved into writing screenplays for the various adaptations of his manga including the much loved Lady Snowblood and an original series in the form of Hanzo the Razor. Lone Wolf and Cub was one of his earliest successes, published between 1970 and 1976 the series spanned 28 volumes and was quickly turned into a movie franchise following the usual pattern of the time which saw six instalments released from 1972 to 1974. Martial arts specialist Tomisaburo Wakayama starred as the ill fated “Lone Wolf”, Ogami, in each of the theatrical movies as the former shogun executioner fights to clear his name and get revenge on the people who framed him for treason and murdered his wife, all with his adorable little son ensconced in a bamboo cart.

When it comes to period exploitation films of the 1970s, one name looms large – Kazuo Koike. A prolific mangaka, Koike also moved into writing screenplays for the various adaptations of his manga including the much loved Lady Snowblood and an original series in the form of Hanzo the Razor. Lone Wolf and Cub was one of his earliest successes, published between 1970 and 1976 the series spanned 28 volumes and was quickly turned into a movie franchise following the usual pattern of the time which saw six instalments released from 1972 to 1974. Martial arts specialist Tomisaburo Wakayama starred as the ill fated “Lone Wolf”, Ogami, in each of the theatrical movies as the former shogun executioner fights to clear his name and get revenge on the people who framed him for treason and murdered his wife, all with his adorable little son ensconced in a bamboo cart.