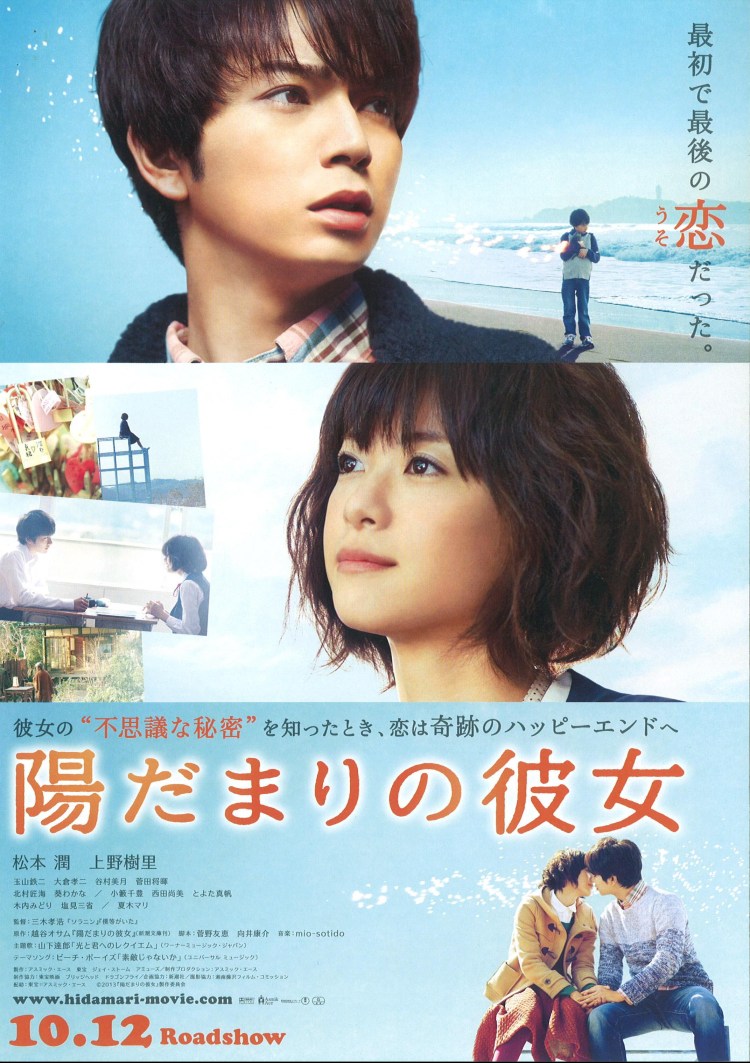

The “jun-ai” boom might have been well and truly over by the time Takahiro Miki’s Girl in the Sunny Place (陽だまりの彼女, Hidamari no Kanojo) hit the screen, but tales of true love doomed are unlikely to go out of fashion any time soon. Based on a novel by Osamu Koshigaya, Girl in the Sunny Place is another genial romance in which teenage friends are separated, find each other again, become happy and then have that happiness threatened, but it’s also one that hinges on a strange magical realism born of the affinity between humans and cats.

The “jun-ai” boom might have been well and truly over by the time Takahiro Miki’s Girl in the Sunny Place (陽だまりの彼女, Hidamari no Kanojo) hit the screen, but tales of true love doomed are unlikely to go out of fashion any time soon. Based on a novel by Osamu Koshigaya, Girl in the Sunny Place is another genial romance in which teenage friends are separated, find each other again, become happy and then have that happiness threatened, but it’s also one that hinges on a strange magical realism born of the affinity between humans and cats.

25 year old Kosuke (Jun Matsumoto) is a diffident advertising executive living a dull if not unhappy life. Discovering he’s left it too late to ask out a colleague, Kousuke is feeling depressed but an unexpected meeting with a client brightens his day. The pretty woman standing in the doorway with the afternoon sun neatly lighting her from behind is an old middle school classmate – Mao (Juri Ueno), whom Kosuke has not seen in over ten years since he moved away from his from town and the pair were separated. Eventually the two get to know each other again, fall in love, and get married but Mao is hiding an unusual secret which may bring an end to their fairytale romance.

Filmed with a breezy sunniness, Girl in the Sunny Place straddles the line between quirky romance and the heartrending tragedy which defines jun-ai, though, more fairytale than melodrama, there is still room for bittersweet happy endings even in the inevitability of tragedy. Following the pattern of many a tragic love story, Miki moves between the present day and the middle school past in which Kosuke became Mao’s only protector when she was mercilessly bullied for being “weird”. Mao’s past is necessarily mysterious – adopted by a policeman (Sansei Shiomi) who found her wandering alone at night, Mao has no memory of her life before the age of 13 and lacks the self awareness of many of the other girls, turning up with messy hair and dressed idiosyncratically. When Kousuke stands up to the popular/delinquent kids making her life a misery, the pair become inseparable and embark on their first romance only to be separated when Kosuke’s family moves away from their hometown of Enoshima.

“Miraculously” meeting again they enjoy a typically cute love story as they work on the ad campaign for a new brassiere collection which everyone else seems to find quite embarrassing. As time moves on it becomes apparent that there’s something more than kookiness in Mao’s strange energy and sure enough, the signs become clear as Mao’s energy fades and her behaviour becomes less and less normal.

The final twist, well signposted as it is, may leave some baffled but is in the best fairytale tradition. Maki films with a well placed warmth, finding the sun wherever it hides and bathing everything in the fuzzy glow of a late summer evening in which all is destined go on pleasantly just as before. Though the (first) ending may seem cruel, the tone is one of happiness and possibility, of partings and reunions, and of the transformative powers of love which endure even if everything else has been forgotten. Beautifully shot and anchored by strong performances from Juri Ueno and Jun Matsumoto, Girl in the Sunny Place neatly sidesteps its melodramatic premise for a cheerfully affecting love story even if it’s the kind that may float away on the breeze.

Original trailer (no subtitles)

Every love story is a ghost story, as the aphorism made popular (though not perhaps coined) by David Foster Wallace goes. For The Tale of Nishio (ニシノユキヒコの恋と冒険, Nishino Yukihiko no Koi to Boken), adapted from the novel by Hiromi Kawakami, this is a literal truth as the hero dies not long after the film begins and then returns to visit an old lover, only to find her gone, having ghosted her own family including a now teenage daughter. The Japanese title, which is identical to Kawakami’s novel, means something more like Yukihiko Nishino’s Adventures in Love which might give more of an indication into his repeated failures to find the “normal” family life he apparently sought, but then his life is a kind of cautionary tale offered up as a fable. What looks like kindness sometimes isn’t, and things done for others can in fact be for the most selfish of reasons.

Every love story is a ghost story, as the aphorism made popular (though not perhaps coined) by David Foster Wallace goes. For The Tale of Nishio (ニシノユキヒコの恋と冒険, Nishino Yukihiko no Koi to Boken), adapted from the novel by Hiromi Kawakami, this is a literal truth as the hero dies not long after the film begins and then returns to visit an old lover, only to find her gone, having ghosted her own family including a now teenage daughter. The Japanese title, which is identical to Kawakami’s novel, means something more like Yukihiko Nishino’s Adventures in Love which might give more of an indication into his repeated failures to find the “normal” family life he apparently sought, but then his life is a kind of cautionary tale offered up as a fable. What looks like kindness sometimes isn’t, and things done for others can in fact be for the most selfish of reasons.

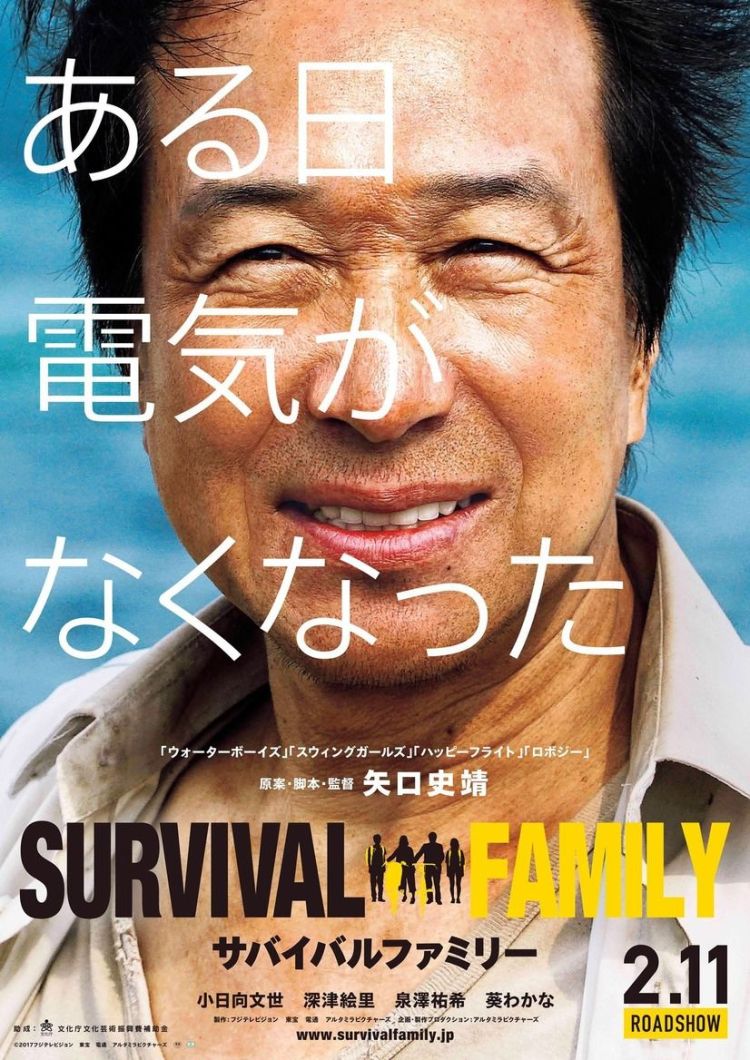

Modern life is full of conveniences, but perhaps they come at a price. Shinobu Yaguchi has made something of a career out of showing the various ways nice people can come together to overcome their problems, but as the problem in Survival Family (サバイバルファミリー) is post-apocalyptic dystopia, being nice might not be the best way to solve it. Nevertheless, the Suzukis can’t help trying as they deal with the cracks already present in their relationships whilst trying to figure out a way to survive in the new, post-electric world.

Modern life is full of conveniences, but perhaps they come at a price. Shinobu Yaguchi has made something of a career out of showing the various ways nice people can come together to overcome their problems, but as the problem in Survival Family (サバイバルファミリー) is post-apocalyptic dystopia, being nice might not be the best way to solve it. Nevertheless, the Suzukis can’t help trying as they deal with the cracks already present in their relationships whilst trying to figure out a way to survive in the new, post-electric world. There are two kinds of people in the world, those who swing and those who…don’t – a metaphor which works just as well for baseball and, by implication, facing life’s challenges as it does for music. Shinobu Yaguchi returns after 2001’s

There are two kinds of people in the world, those who swing and those who…don’t – a metaphor which works just as well for baseball and, by implication, facing life’s challenges as it does for music. Shinobu Yaguchi returns after 2001’s

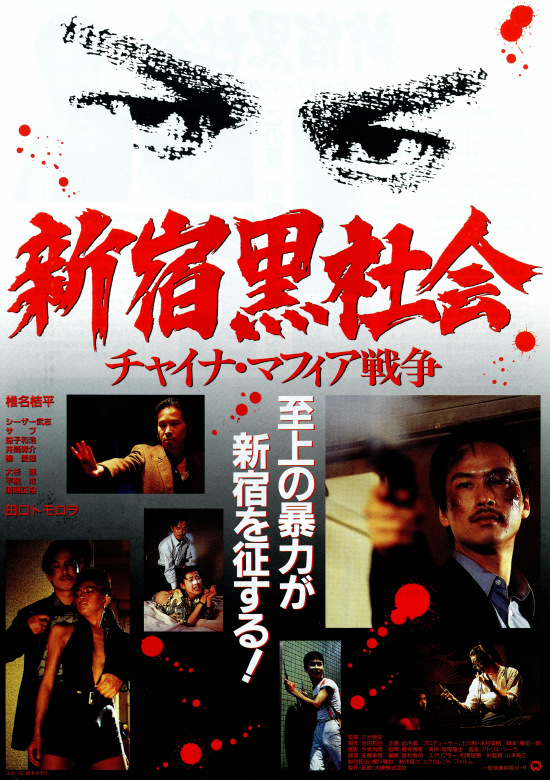

These days Takashi Miike is known as something of an enfant terrible whose rate of production is almost impossible to keep up with and regularly defies classification. Pressed to offer some kind of explanation to the uninitiated, most will point to the unsettling horror of

These days Takashi Miike is known as something of an enfant terrible whose rate of production is almost impossible to keep up with and regularly defies classification. Pressed to offer some kind of explanation to the uninitiated, most will point to the unsettling horror of  Ryosuke Hashiguchi returns after an eight year absence with All Around Us (ぐるりのこと。Gururi no Koto) and eschews most of his pressing themes up this by point by opting to depict a few “scenes from a marriage” in post-bubble era Japan. Set against the backdrop of an extremely turbulent decade which was plagued by natural disasters, terrorism, and shocking criminal activity Hashiguchi shows us the enduring love of one ordinary couple who, finding themselves pulled apart by tragedy, gradually grow closer through their shared grief and disappointment.

Ryosuke Hashiguchi returns after an eight year absence with All Around Us (ぐるりのこと。Gururi no Koto) and eschews most of his pressing themes up this by point by opting to depict a few “scenes from a marriage” in post-bubble era Japan. Set against the backdrop of an extremely turbulent decade which was plagued by natural disasters, terrorism, and shocking criminal activity Hashiguchi shows us the enduring love of one ordinary couple who, finding themselves pulled apart by tragedy, gradually grow closer through their shared grief and disappointment.

When it comes to cinematic adaptations of popular novelists, Keigo Higashino seems to have received more attention than most. Perhaps this is because he works in so many different genres from detective fiction (including his all powerful Galileo franchise) to family melodrama but it has to be said that his work manages to home in on the kind of films which have the potential to become a box office smash. The Letter (手紙, Tegami) finds him in the familiar territory of sentimental drama as its put upon protagonist battles unfairness and discrimination based on a set of rigid social codes.

When it comes to cinematic adaptations of popular novelists, Keigo Higashino seems to have received more attention than most. Perhaps this is because he works in so many different genres from detective fiction (including his all powerful Galileo franchise) to family melodrama but it has to be said that his work manages to home in on the kind of films which have the potential to become a box office smash. The Letter (手紙, Tegami) finds him in the familiar territory of sentimental drama as its put upon protagonist battles unfairness and discrimination based on a set of rigid social codes.