Adolescent romance is complicated enough at the best of times but the barriers are ever higher if you happen to be gay in a less than tolerant society. Ryosuke Hashiguchi’s second feature Like Grains of Sand (渚のシンドバッド, Nagisa no Sinbad) takes a slight step back in time from A Touch of Fever but retains its very ordinary world as a collection of boys and girls embark on a process of self discovery whilst also locked into the unbreakable straightjacket of the high school world.

Adolescent romance is complicated enough at the best of times but the barriers are ever higher if you happen to be gay in a less than tolerant society. Ryosuke Hashiguchi’s second feature Like Grains of Sand (渚のシンドバッド, Nagisa no Sinbad) takes a slight step back in time from A Touch of Fever but retains its very ordinary world as a collection of boys and girls embark on a process of self discovery whilst also locked into the unbreakable straightjacket of the high school world.

Ito (Yoshinori Okada) is an ordinary high school boy with a crush on his oblivious best friend, Yoshida (Kouta Kusano). Though Yoshida defends him from the homophobic bullies in his class, he seems confused about his true feelings, at once stating that what he feels for Ito is more that friendship but also unwilling to address what that “more” may mean. After Ito’s father intercepts a reply to a personal ad he placed hoping to meet older men, Ito ends up at a psychiatrist’s office where his father hopes he might be “cured” though the doctor is quick to point out that they no longer view homosexuality as a medical matter.

Whilst at the clinic, Ito strikes a up a friendship with another girl from his class, Aihara (Ayumi Hamasaki) – a recent transfer student, who, we learn, has experienced a traumatic event which is also the reason she had to leave her previous place of education. Aihara is the only person with whom Ito can discuss his sexuality honestly though he’s also sure to “protect” Yoshida by claiming he rejected his advances outright rather than explaining the confusing series of events as they actually occurred. When Aihara and Ito accidentally end up on an awkward double date with Yoshida and his girlfriend Shimizu (Kumi Takada), Yoshida also begins to develop an (unreturned) attraction to Aihara which only further complicates the delicate nature of the growing emotional ties among this small group of young people.

A real step up from the promising yet flawed A Touch of Fever, Like Grains of Sand proves Hashiguchi’s skill in building an extremely natural environment filled with believable well rounded characters. The high school world is a cruel one populated by unsteady teenagers, each by times rebellious and insecure. Aihara, as a recent transfer student, is already an outsider but finds herself excluded even further thanks to her direct and aloof character. Early on in the film two of the other girls, evidently the popular set, begin running a bizarre extortion scam in which they claim a friend of theirs has fallen pregnant and needs to get an abortion right away so they’re collecting money to help her. Shimizu doesn’t seem to buy their explanation but is bamboozled into paying up to not cause offence. Aihara, however, brands the pair “sympathy fascists” and abruptly walks away.

Ito is also an outsider, though partially a self-exile, longing yet fearful. At the beginning of the film he’s overwhelmed watching the unexpectedly sensual action of Yoshida pouring a bag of sand into a container destined for the sports field. After they’ve finished, Ito faints right in front of his fellow schoolmates, though at least the convenient hot weather might prove his ally. When the other boys draw a lewd drawing on the blackboard and start teasing Ito, Yoshida comes to his rescue even though he knows that’s likely to cause trouble for himself. Reassuring his friend that it would be OK even if it was true, Yoshida continues to act in a non committal manner. Ito confesses, Yoshida accepts the confession but at the same time is uncertain permitting both a kiss and an embrace before pushing his friend away and leaving as if nothing out of the ordinary had happened.

After an impromptu hug on a rooftop, Shimizu makes attempt to ask Aihara is she’s gay with no particular judgement attached except a slight reticence in terms of language. Aihara seems slightly confused, replying only that Shimizu is preoccupied with the wrong questions. Later, Ito ends up escorting the smitten Yoshida to Aihara’s childhood home where things come to a climax during an intense finale on a secluded beach. Night is falling and Ito has put on Aihara’s white dress and hat while she goes for a swim just as Yoshida returns for a second stab at confessions. Hiding behind a rock while Yoshida thinks Ito is her, Aihara continues to conduct a philosophically based dissection of Yoshida’s approach to sexuality. She asks him, would you still love me if I were a man, and if not, is it more that what you want is a woman and not really “me” at all, along with other questions designed to prompt a response as to the importance of gender when it comes to love. That all this happens as a kind of Cyrano de Bergerac-like three way sequence with Ito dressed as Aihara, and Yoshida talking to Aihara through someone else only lends to the surreal, increasingly symbolic atmosphere.

Gentle and softly nuanced, Like Grains of Sand is a delicate exploration of ordinary young people caught in a confusing storm of emotions as they each address their burgeoning sexuality. Rich with complexity yet also effortlessly straightforward, Hashiguchi has created a beautifully naturalistic portrait of adolescence in flux which is filled with empathy and acceptance for each of its angst ridden teens and even for their less forgiving friends and relatives. A noticeable progression from Touch of Fever, Like Grains of Sand further proves Hashiguchi’s skill for character drama and marks him as one of the most incisive writer/directors working today.

Original trailer (no subtitles)

The Japanese title of the film, Nagisa no Sinbad, is also the title of a hit single by 1970s super duo Pink Lady! (Beware – extremely catchy)

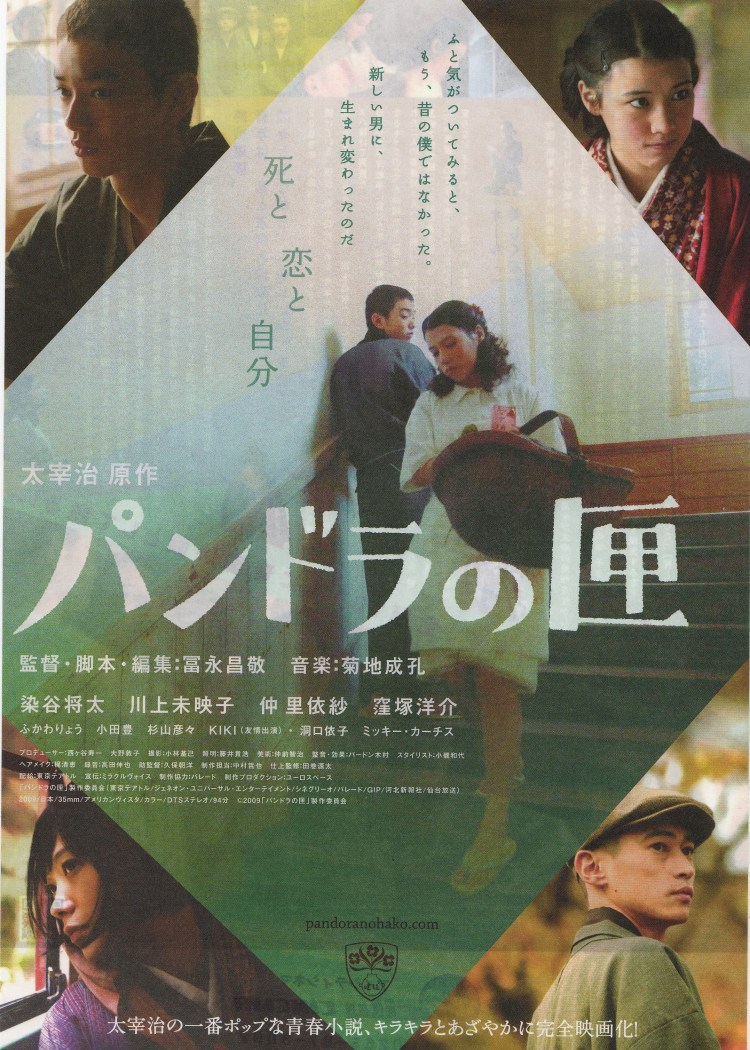

Osamu Dazai is one of the twentieth century’s literary giants. Beginning his career as a student before the war, Dazai found himself at a loss after the suicide of his idol Ryunosuke Akutagawa and descended into a spiral of hedonistic depression that was to mark the rest of his life culminating in his eventual drowning alongside his mistress Tomie in a shallow river in 1948. 2009 marked the centenary of his birth and so there were the usual tributes including a series of films inspired by his works. In this respect, Pandora’s Box (パンドラの匣, Pandora no Hako) is a slightly odd choice as it ranks among his minor, lesser known pieces but it is certainly much more upbeat than the nihilistic Fallen Angel or the fatalistic

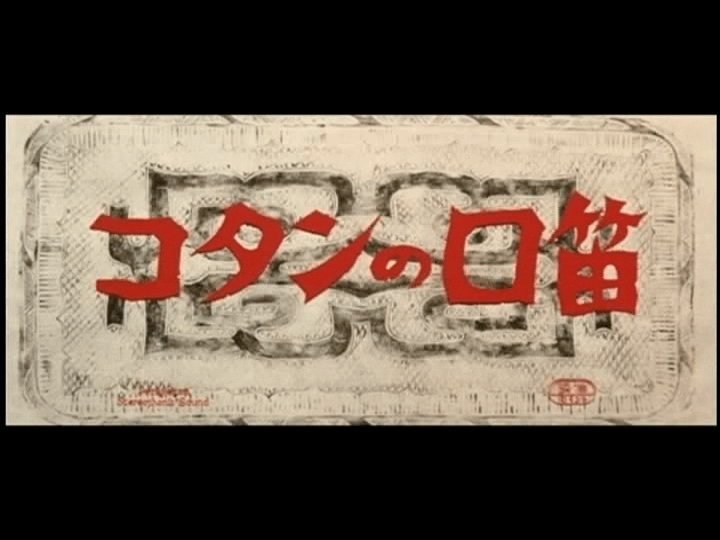

Osamu Dazai is one of the twentieth century’s literary giants. Beginning his career as a student before the war, Dazai found himself at a loss after the suicide of his idol Ryunosuke Akutagawa and descended into a spiral of hedonistic depression that was to mark the rest of his life culminating in his eventual drowning alongside his mistress Tomie in a shallow river in 1948. 2009 marked the centenary of his birth and so there were the usual tributes including a series of films inspired by his works. In this respect, Pandora’s Box (パンドラの匣, Pandora no Hako) is a slightly odd choice as it ranks among his minor, lesser known pieces but it is certainly much more upbeat than the nihilistic Fallen Angel or the fatalistic  The Ainu have not been a frequent feature of Japanese filmmaking though they have made sporadic appearances. Adapted from a novel by Nobuo Ishimori, Whistling in Kotan (コタンの口笛, Kotan no Kuchibue, AKA Whistle in My Heart) provides ample material for the generally bleak Naruse who manages to mine its melodramatic set up for all of its heartrending tragedy. Rather than his usual female focus, Naruse tells the story of two resilient Ainu siblings facing not only social discrimination and mistreatment but also a series of personal misfortunes.

The Ainu have not been a frequent feature of Japanese filmmaking though they have made sporadic appearances. Adapted from a novel by Nobuo Ishimori, Whistling in Kotan (コタンの口笛, Kotan no Kuchibue, AKA Whistle in My Heart) provides ample material for the generally bleak Naruse who manages to mine its melodramatic set up for all of its heartrending tragedy. Rather than his usual female focus, Naruse tells the story of two resilient Ainu siblings facing not only social discrimination and mistreatment but also a series of personal misfortunes. Akio Jissoji has one of the most diverse filmographies of any director to date. In a career that also encompasses the landmark tokusatsu franchise Ultraman and a large selection of children’s TV, Jissoji made his mark as an avant-garde director through his three Buddhist themed art films for ATG. Summer of Ubume (姑獲鳥の夏, Ubume no Natsu) is a relatively late effort and finds Jissoji adapting a supernatural mystery novel penned by Natsuhiko Kyogoku neatly marrying most of his central concerns into one complex detective story.

Akio Jissoji has one of the most diverse filmographies of any director to date. In a career that also encompasses the landmark tokusatsu franchise Ultraman and a large selection of children’s TV, Jissoji made his mark as an avant-garde director through his three Buddhist themed art films for ATG. Summer of Ubume (姑獲鳥の夏, Ubume no Natsu) is a relatively late effort and finds Jissoji adapting a supernatural mystery novel penned by Natsuhiko Kyogoku neatly marrying most of his central concerns into one complex detective story. Another vehicle for post-war singing star Hibari Misora, With a Song in her Heart (希望の乙女, Kibo no Otome) was created in celebration of the tenth anniversary of her showbiz debut. As such, it has a much higher song to drama ratio than some of her other efforts and mixes fantasy production numbers with band scenes as Hibari takes centre stage playing a young woman from the country who comes to the city in the hopes of becoming a singing star.

Another vehicle for post-war singing star Hibari Misora, With a Song in her Heart (希望の乙女, Kibo no Otome) was created in celebration of the tenth anniversary of her showbiz debut. As such, it has a much higher song to drama ratio than some of her other efforts and mixes fantasy production numbers with band scenes as Hibari takes centre stage playing a young woman from the country who comes to the city in the hopes of becoming a singing star. If you’re going on the run you might as well do it in style. Wait, that’s terrible advice isn’t it? Perhaps there’s something to be said for planning a cunning double bluff by becoming so flamboyant that everyone starts ignoring you out of a mild sense of embarrassment but that’s quite a risk for someone whose original gamble has so obviously gone massively wrong. An adaptation of a manga, Katsuhito Ishii’s debut feature Sharkskin Man and Peach Hip Girl (鮫肌男と桃尻女, Samehada Otoko to Momojiri Onna) follows a mysterious criminal trying to head off the gang he just stole a bunch of money from whilst also accompanying a strange young girl, also on the run but from her perverted, hotel owning “uncle” who has also sent an equally eccentric hitman after the absconding pair with instructions to bring her back.

If you’re going on the run you might as well do it in style. Wait, that’s terrible advice isn’t it? Perhaps there’s something to be said for planning a cunning double bluff by becoming so flamboyant that everyone starts ignoring you out of a mild sense of embarrassment but that’s quite a risk for someone whose original gamble has so obviously gone massively wrong. An adaptation of a manga, Katsuhito Ishii’s debut feature Sharkskin Man and Peach Hip Girl (鮫肌男と桃尻女, Samehada Otoko to Momojiri Onna) follows a mysterious criminal trying to head off the gang he just stole a bunch of money from whilst also accompanying a strange young girl, also on the run but from her perverted, hotel owning “uncle” who has also sent an equally eccentric hitman after the absconding pair with instructions to bring her back. Junichi Inoue is better known as a screenwriter and frequent collaborator of avant-garde/pink film provocateur Koji Wakamatsu. A Woman and a War (戦争と一人の女, Senso to Hitori no Onna) marks his first time in the director’s chair and finds him working with someone else’s script but staying firmly within the pink genre. Adapted from a contemporary novel by Ango Sakaguchi published in 1946, A Woman and a War is an intense look at domestic female suffering during a time generalised chaos.

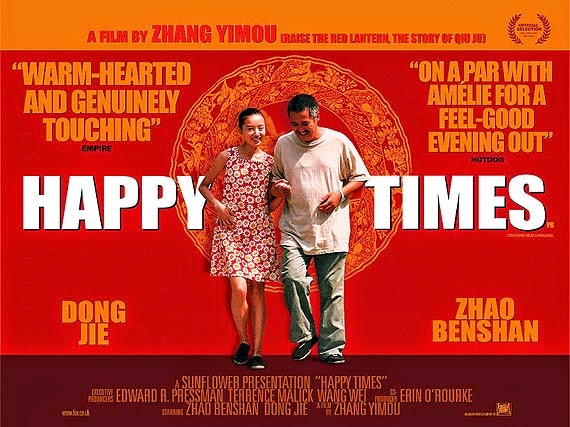

Junichi Inoue is better known as a screenwriter and frequent collaborator of avant-garde/pink film provocateur Koji Wakamatsu. A Woman and a War (戦争と一人の女, Senso to Hitori no Onna) marks his first time in the director’s chair and finds him working with someone else’s script but staying firmly within the pink genre. Adapted from a contemporary novel by Ango Sakaguchi published in 1946, A Woman and a War is an intense look at domestic female suffering during a time generalised chaos. Possibly the most successful of China’s Fifth Generation filmmakers, Zhang Yimou is not particularly known for his sense of humour though Happy Times (幸福时光, Xìngfú Shíguāng) is nothing is not drenched in irony. Less directly aimed at social criticism, Happy Times takes a sideswipe at modern culture with its increasing consumerism, lack of empathy, and relentless progress yet it also finds good hearted people coming together to help each other through even if they do it in slightly less than ideal ways.

Possibly the most successful of China’s Fifth Generation filmmakers, Zhang Yimou is not particularly known for his sense of humour though Happy Times (幸福时光, Xìngfú Shíguāng) is nothing is not drenched in irony. Less directly aimed at social criticism, Happy Times takes a sideswipe at modern culture with its increasing consumerism, lack of empathy, and relentless progress yet it also finds good hearted people coming together to help each other through even if they do it in slightly less than ideal ways.

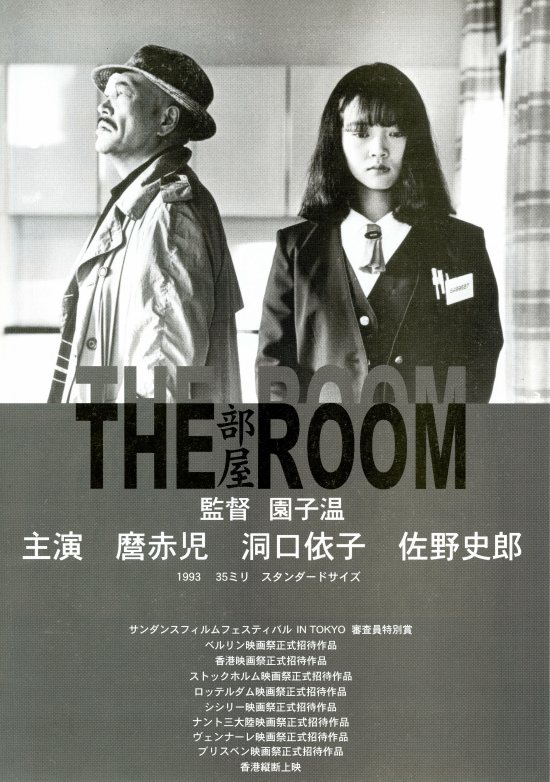

Though the later work of Sion Sono is often noted for its cinematic excess, his earlier career saw him embracing the art of minimalism. The Room (部屋, Heya) finds him in the realms of existentialist noir as a grumpy hitman whiles away his remaining time in the search for the perfect apartment guided only by a detached estate agent.

Though the later work of Sion Sono is often noted for its cinematic excess, his earlier career saw him embracing the art of minimalism. The Room (部屋, Heya) finds him in the realms of existentialist noir as a grumpy hitman whiles away his remaining time in the search for the perfect apartment guided only by a detached estate agent. Yoji Yamada’s films have an almost Pavlovian effect in that they send even the most hard hearted of viewers out for tissues even before the title screen has landed. Kabei (母べえ), based on the real life memoirs of script supervisor and frequent Kurosawa collaborator Teruyo Nogami, is a scathing indictment of war, militarism and the madness of nationalist fervour masquerading as a “hahamono”. As such it is engineered to break the hearts of the world, both in its tale of a self sacrificing mother slowly losing everything through no fault of her own but still doing her best for her daughters, and in the crushing inevitably of its ever increasing tragedy.

Yoji Yamada’s films have an almost Pavlovian effect in that they send even the most hard hearted of viewers out for tissues even before the title screen has landed. Kabei (母べえ), based on the real life memoirs of script supervisor and frequent Kurosawa collaborator Teruyo Nogami, is a scathing indictment of war, militarism and the madness of nationalist fervour masquerading as a “hahamono”. As such it is engineered to break the hearts of the world, both in its tale of a self sacrificing mother slowly losing everything through no fault of her own but still doing her best for her daughters, and in the crushing inevitably of its ever increasing tragedy.