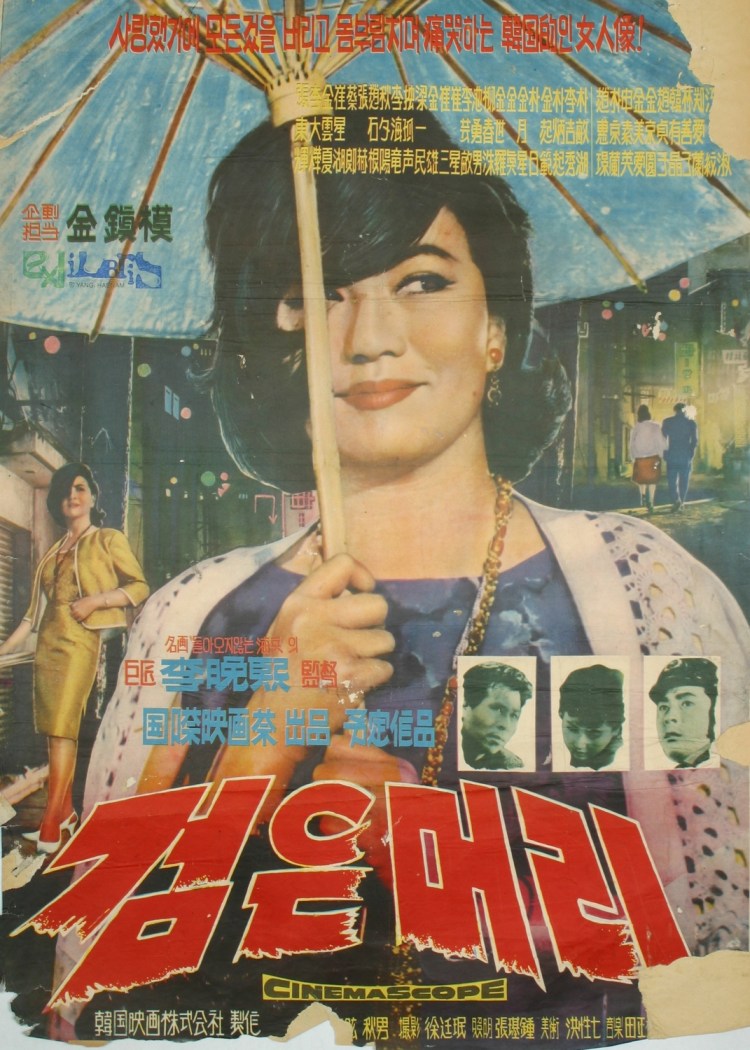

The Korea of 1964 was one beginning to look forwards towards a new global future rather than back towards the turbulent colonial past, but the rapid leap forward into a new society had perhaps left an entire generation behind as they prepared to watch their children reject everything they’d strived for in search of “modernity”. 1964’s The Body Confession (肉体의 告白 / 육체의 고백, Yukche-ui Gobak) is the story of one such woman. Widowed young, she turned to sex work in order to support her three daughters in the hope that sending them to university would win them wealthy husbands only for her daughters to encounter the very problems she worked so hard for them to avoid.

The Korea of 1964 was one beginning to look forwards towards a new global future rather than back towards the turbulent colonial past, but the rapid leap forward into a new society had perhaps left an entire generation behind as they prepared to watch their children reject everything they’d strived for in search of “modernity”. 1964’s The Body Confession (肉体의 告白 / 육체의 고백, Yukche-ui Gobak) is the story of one such woman. Widowed young, she turned to sex work in order to support her three daughters in the hope that sending them to university would win them wealthy husbands only for her daughters to encounter the very problems she worked so hard for them to avoid.

The heroine, a veteran sex worker known as The President (Hwang Jung-seun), has become a kind of community leader in the red light district largely catering to American servicemen in the post-war era. While she labours away in the brothels of Busan, her three daughters are living happily in Seoul believing that she runs a successful fashion store which is how she manages to send them their tuition money every month. The President goes to great lengths to protect them from the truth, even enlisting a fashion store owning friend when the girls visit unexpectedly. Nevertheless, she is becoming aware that her position is becoming ever more precarious – as an older woman with a prominent limp she can no longer command the same kind of custom as in her youth and is increasingly dependent on the support of her fellow sex workers who have immense respect for her and, ironically, view her as a maternal figure in the often dangerous underworld environment.

This central idea of female solidarity is the one which has underpinned The President’s life and allowed her to continue living despite the constant hardship she has faced. Yet she is terrified that her daughters may one day find out about her “shameful” occupation and blame her for it, or worse that it could frustrate her hopes for them that they marry well and avoid suffering a similar fate. Despite having, in a sense, achieved a successful career in the red light district, The President wants her daughters to become respectable wives and mothers rather than achieve success in their own rights or be independent. Thus her goal of sending them to university was not for their education but only to make them more attractive to professional grade husbands.

The daughters, however, are modern women and beginning to develop differing ideas to their mother’s vision of success. Oldest daughter Song-hui (Lee Kyoung-hee) has fallen in love with a lowly intellectual truck driver (Kim Jin-kyu) who has placed all his hopes on winning a literary competition. He is a war orphan and has no money or family connections. Meanwhile, second daughter Dong-hui (Kim Hye-jeong) has failed her exams twice and developed a reputation as a wild girl. Toying with a poor boy, she eventually drifts into a relationship with the wealthy son of a magnate (Lee Sang-sa) but fails to realise that he too is only toying with her and intends to honour his family’s wishes by going through with an arranged marriage. Only youngest daughter Yang-hui (Tae Hyun-sil) is living the dream by becoming a successful concert musician and planning to marry a diplomat’s son.

The three daughters have, in a sense, suffered because of their mother’s ideology which encourages them to place practical concerns above the emotional. Song-hui is conflicted in knowing that she will break her mother’s heart by marrying a man with no money or family but also knows that she will choose him all the same. Dong-hui, by contrast, enthusiastically chases Man-gyu for his money but naively fails to realise that he is selfish and duplicitous. In another evocation of the female solidarity that informs the film, Man-gyu’s fiancée Mi-ri eventually dumps him on witnessing the way he treats Dong-hui, roundly rejecting the idea of being shackled to a chauvinistic man who assumes it is his right to have his way with whomever he chooses and face no consequences. Like Song-hui, Mi-ri breaks with tradition in breaking off her engagement against her parents’ wishes and reserving her own right to determine her future.

Yang-hui, whose future eventually works out precisely because of the sacrifices made on her behalf by her mother, turns out to be her harshest critic, rejecting The President on learning the truth and attempting to sever their connection by repaying all the “ill-gotten” investment. Her wealthy husband, however, turns out to be unexpectedly sympathetic in pointing out that her mother has suffered all these long years only to buy her future happiness and that now is the time they both should be thanking her. Meanwhile, The President has become despondent in realising she is out of road. There is no longer much of a place for her in the red light district, and she has nowhere left to turn. Only the kindly Maggie, another sex worker who has been a daughter to her all this time, is prepared to stand by her and take care of her in her old age.

The gulf between the two generations is neatly symbolised by the surprising inclusion of stock footage from the April 19 rising against the corrupt regime of Rhee Syngman which led to a brief period of political freedom before the dictatorship of Park Chung-hee took power in 1961. The poor intellectual author whom The President dismissed, eventually becomes an internationally renowned literary figure after being published abroad while the wealthy magnate’s son turns out to be a louse. The President staked her life on the old feudal ways of ingratiating oneself with privilege by playing by its rules, but the world has moved on and it’s up to the young to forge their own destinies rather than blindly allowing those in power to do as they please. Sadly for The President, her sacrifices will be appreciated only when it’s too late and her desire for her daughters to escape the hardship she had faced misunderstood as greed and snobbishness. There is no longer any place for her old fashioned ideas in the modern era and her daughters will need to learn to get by on their own while accepting that their future was built on maternal sacrifice.

The Body Confession was screened as part of the 2019 Udine Far East Film Festival. It is also available to stream online via the Korean Film Archive’s YouTube Channel.

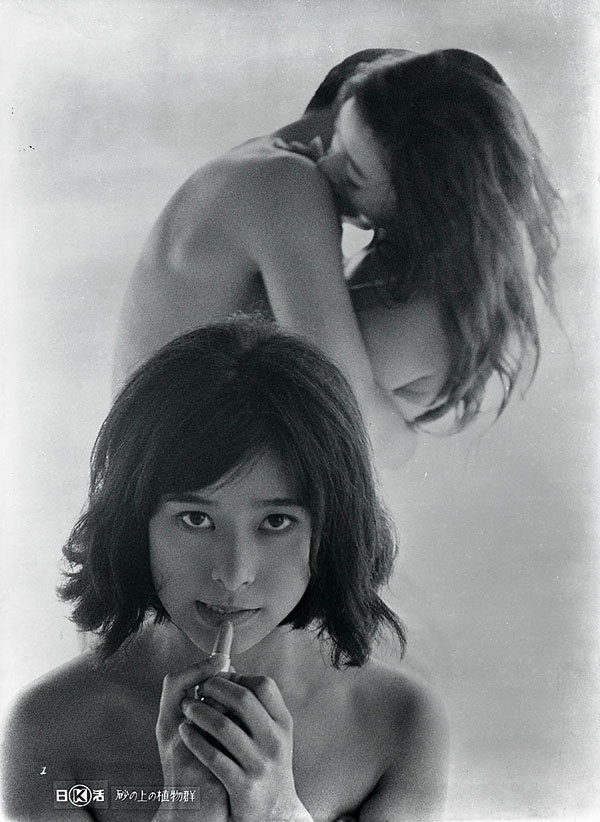

Despite being among the directors who helped to usher in what would later be called the Japanese New Wave, Ko Nakahira remains in relative obscurity with only his landmark movie of the Sun Tribe era, Crazed Fruit, widely seen abroad. Like the other directors of his generation Nakahira served his time in the studio system working on impersonal commercial projects but by 1964 which saw the release of another of his most well regarded films Only on Mondays, Nakahira had begun to give free reign to experimentation much to the studio boss’ chagrin. Flora on the Sand (砂の上の植物群, Suna no Ue no Shokubutsu-gun), adapted from the novel by Junnosuke Yoshiyuki, puts an absurd, surreal twist on the oft revisited salaryman midlife crisis as its conflicted hero muses on the legacy of his womanising father while indulging in a strange ménage à trois with two sisters, one of whom to he comes to believe he may also be related to.

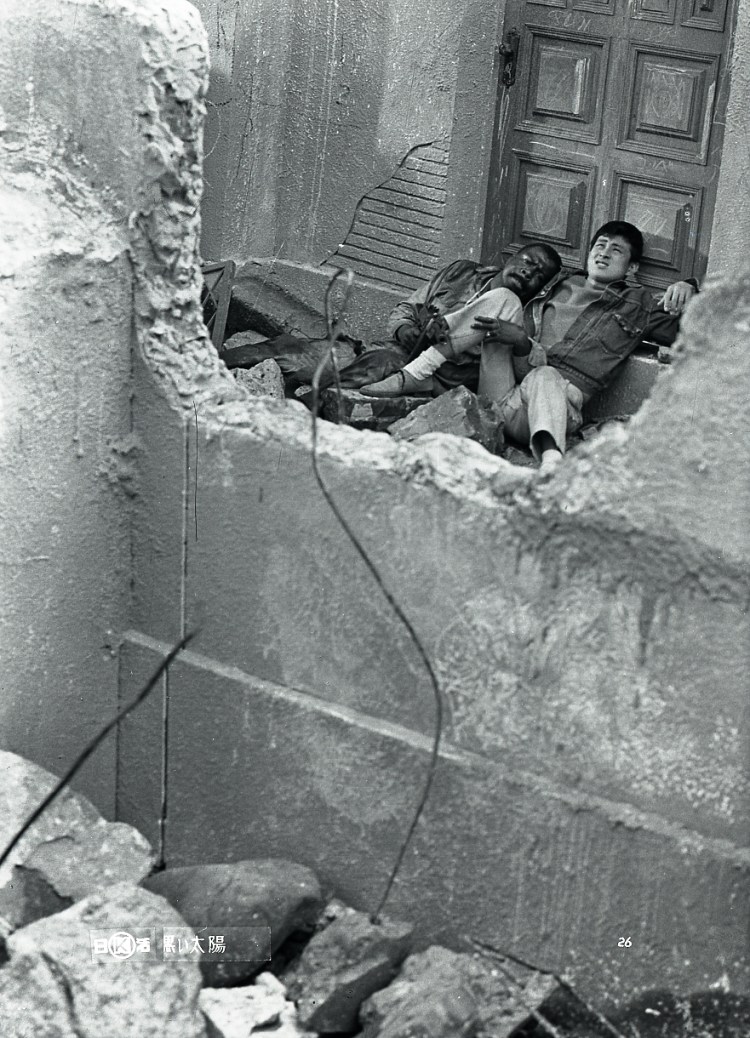

Despite being among the directors who helped to usher in what would later be called the Japanese New Wave, Ko Nakahira remains in relative obscurity with only his landmark movie of the Sun Tribe era, Crazed Fruit, widely seen abroad. Like the other directors of his generation Nakahira served his time in the studio system working on impersonal commercial projects but by 1964 which saw the release of another of his most well regarded films Only on Mondays, Nakahira had begun to give free reign to experimentation much to the studio boss’ chagrin. Flora on the Sand (砂の上の植物群, Suna no Ue no Shokubutsu-gun), adapted from the novel by Junnosuke Yoshiyuki, puts an absurd, surreal twist on the oft revisited salaryman midlife crisis as its conflicted hero muses on the legacy of his womanising father while indulging in a strange ménage à trois with two sisters, one of whom to he comes to believe he may also be related to. Being stood up is a painful experience at the best of times, but when you’ve been in prison for three whole years and no one comes to meet you, it is more than usually upsetting. Sixth generation Oyabun of the Ona clan, Daisaku, has made a new friend whilst inside – Taro is a younger man, slightly geeky and obsessed with bombs. Actually, he’s a bit wimpy and was in for public urination (he also threw a firecracker at the policeman who took issue with his call of nature) but will do as a henchman in a pinch. Daisaku wanted him to see all of his yakuza guys showering him with praise but only his son actually turns up and even that might have been an accident.

Being stood up is a painful experience at the best of times, but when you’ve been in prison for three whole years and no one comes to meet you, it is more than usually upsetting. Sixth generation Oyabun of the Ona clan, Daisaku, has made a new friend whilst inside – Taro is a younger man, slightly geeky and obsessed with bombs. Actually, he’s a bit wimpy and was in for public urination (he also threw a firecracker at the policeman who took issue with his call of nature) but will do as a henchman in a pinch. Daisaku wanted him to see all of his yakuza guys showering him with praise but only his son actually turns up and even that might have been an accident.