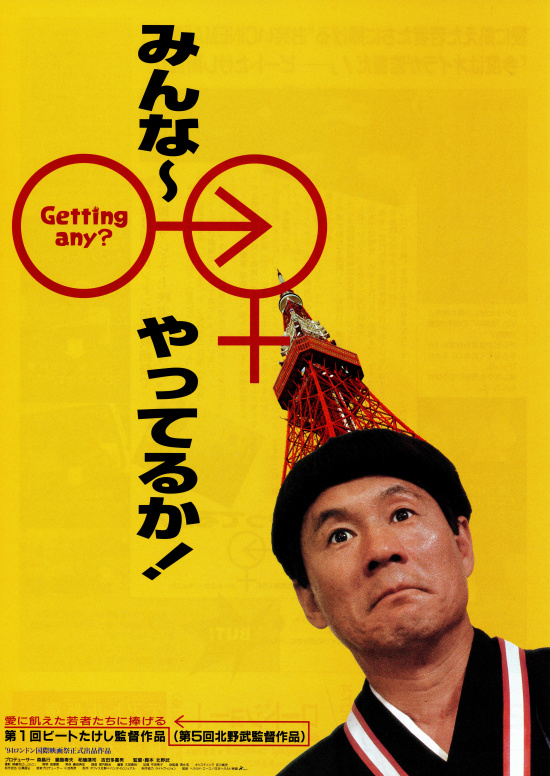

Despite his reputation for violent gangster dramas and melancholy arthouse pieces, Takeshi Kitano is one of Japan’s most successful comedians and began his career as half of an irreverent and anarchic “manzai” comedy double act. 1995’s Getting Any? (みんな~やってるか!Minna – yatteruka!) is his first big screen comedy and loosely takes the form of a series of variety-style skits in which a lonely, hapless middle-aged man tries on various different personas in the pursuit of his goal but remains an isolated bystander in the surreal events which eventually engulf him. Part bawdy, sleazy sex comedy and satire on the death of materialism in the post-bubble world, Getting Any? is a cineliterate journey through Showa era pop culture peppered with gratuitous nudity and absurd running jokes.

Despite his reputation for violent gangster dramas and melancholy arthouse pieces, Takeshi Kitano is one of Japan’s most successful comedians and began his career as half of an irreverent and anarchic “manzai” comedy double act. 1995’s Getting Any? (みんな~やってるか!Minna – yatteruka!) is his first big screen comedy and loosely takes the form of a series of variety-style skits in which a lonely, hapless middle-aged man tries on various different personas in the pursuit of his goal but remains an isolated bystander in the surreal events which eventually engulf him. Part bawdy, sleazy sex comedy and satire on the death of materialism in the post-bubble world, Getting Any? is a cineliterate journey through Showa era pop culture peppered with gratuitous nudity and absurd running jokes.

After watching a very 1980s “aspirational” movie in which a good looking, wealthy young salaryman type gives a young lady a lift in his flashy convertible in which they later end up having sex, Asao (Dankan), watching at home in his pants with his grandpa sitting behind him, decides the reason he hasn’t got any luck with women is that he doesn’t have a car. So, he goes and gets one from a very strange salesman but as he doesn’t have much money the car he gets is, well, it’s unlikely to get stolen, and he still isn’t getting anywhere. He tries a convertible too but that’s no good. Then he starts fantasising about air hostesses, decides to become an actor, gets mistaken for a top yakuza hitman, and comes into contact with a pair of mad scientists who want to turn him invisible.

Asao has only one goal – to have sex with a lady (preferably in a car), but he never stops to think of his potential partners as anything more than a receptacle for his desires. Consequently, he refuses to look at himself or consider the ways he might be getting in the way of his own needs, but constantly chases a quick fix thinking that the reason women don’t want him is because of something material that he lacks. He thinks the path to sexual success lies in cars, money, status, and finally technology, but none of these things really matter while Asao remains Asao.

As part of his journey, passive as it is, Asao does not always remain Asao, or at least the Asao he was for very long. Having failed to be the sort of man who can woo with car, he tries acting – literally playing a part, at which he seems quite good except for going “overboard”. An incident on an aeroplane sees him mistaken for a top yakuza which he is less good at but every mistake only ever works out in his favour. Thanks to his involvement with the mad scientists whom he allows to experiment on him so that he can go peeping in the women’s baths, Asao will finally become another kind of creature entirely, literally reduced to feeding off the excrement his nation has recently produced.

Kitano works in just about every element of almost “retro” pop-culture he can think of from the amusing soundtrack of Showa era hits and references to famous unsolved crimes to a hitman named “Joe Shishido” (star of Branded to Kill), the Zatoichi series, a Lone Wolf and Cub ventriloquist dummy duo, the Invisible Man, Ghostbusters, The Fly, and finally Toho’s tokusatsu classics culminating a lengthy skit inspired by Mothra including the iconic Mothra song given new lyrics and the same old dance performed by two full-sized ladies. Though most viewers will be able to spot the joke even without quite understanding it, some knowledge of Japanese pop-culture from the ‘70s and ‘80s will undoubtedly help.

The central joke revolves around Asao’s fecklessness as he repeatedly fails at each of his schemes, only occasionally succeeding and then by accident, and not for very long. A charmless literalist who lacks the imagination to achieve his goals in a more natural way, Asao fails to learn anything at all, engulfed by one surreal situation after another. It does however give Kitano the excuse to indulge Asao’s flights of fancy as his sexual frustration sends him off into a series of bizarre reveries involving topless women desperate to make love to the suave male stand-in Asao has imagined. Filled with silly slapstick humour and frequent nudity, Kitano’s subtle satire may get lost but even if the joke begins to wear thin just as “flyman” finally lands on his object of desire, there is plenty of amusement on offer for fans of lowbrow humour.

Getting Any? is released on blu-ray by Third Window Films on 16th October, 2017.

Original trailer (English subtitles)

“The Mad Monk” sounds like a great name for a creepy ghost, emerging robed and chanting from the shadows to make you fear for your mortal soul. Sadly, The Mad Monk (濟公, Jì Gōng) features only one “ghost”, but it might just be the cutest in cinema history. The second of Johnnie To’s Shaw Brothers collaborations with comedy star Stephen Chow is another wisecracking romp in which Chow revels in his smart alec superiority, settling bets made in heaven and eventually vowing to spread peace and love across the whole world.

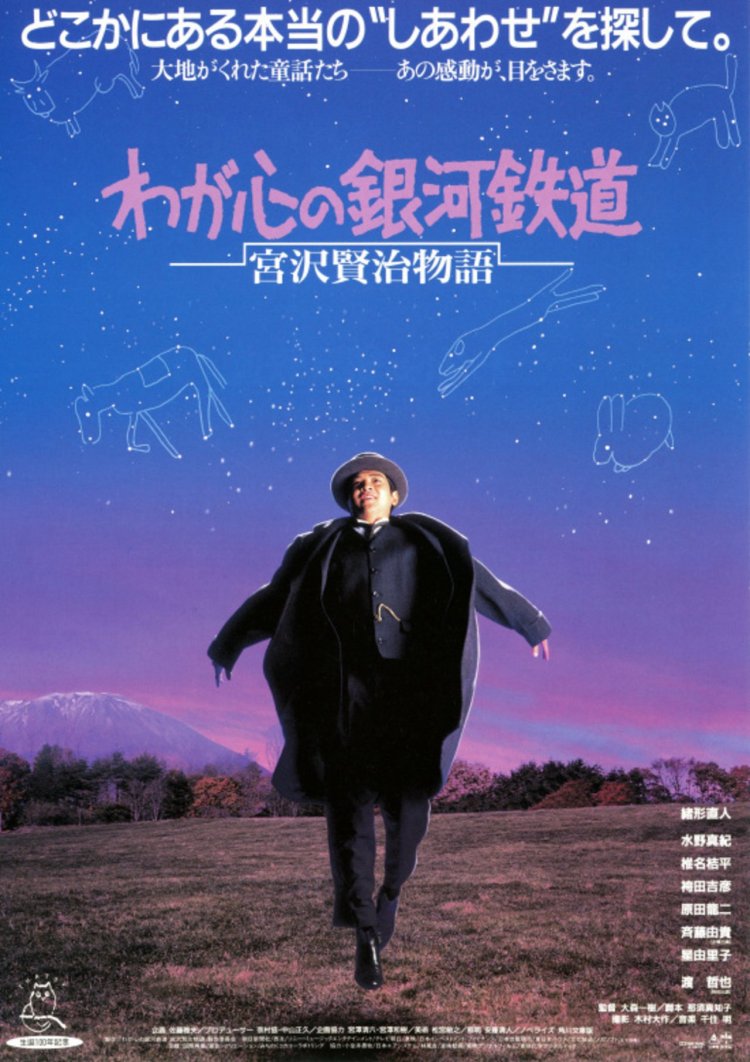

“The Mad Monk” sounds like a great name for a creepy ghost, emerging robed and chanting from the shadows to make you fear for your mortal soul. Sadly, The Mad Monk (濟公, Jì Gōng) features only one “ghost”, but it might just be the cutest in cinema history. The second of Johnnie To’s Shaw Brothers collaborations with comedy star Stephen Chow is another wisecracking romp in which Chow revels in his smart alec superiority, settling bets made in heaven and eventually vowing to spread peace and love across the whole world. Kenji Miyazawa is one of the giants of modern Japanese literature. Studied in schools and beloved by children everywhere, Night on the Galactic Railroad has become a cultural touchstone but Miyazawa died from pneumonia at 37 years of age long before his work was widely appreciated. Night Train to the Stars (わが心の銀河鉄道 宮沢賢治物語, Waga Kokoro no Ginga Tetsudo: Miyazawa Kenji no Monogatari), commissioned to mark the centenary of Miyazawa’s birth, attempts to tell his story, set as it is against the backdrop of rising militarism.

Kenji Miyazawa is one of the giants of modern Japanese literature. Studied in schools and beloved by children everywhere, Night on the Galactic Railroad has become a cultural touchstone but Miyazawa died from pneumonia at 37 years of age long before his work was widely appreciated. Night Train to the Stars (わが心の銀河鉄道 宮沢賢治物語, Waga Kokoro no Ginga Tetsudo: Miyazawa Kenji no Monogatari), commissioned to mark the centenary of Miyazawa’s birth, attempts to tell his story, set as it is against the backdrop of rising militarism.

Stephen Chow has always been a force of nature but even before making his name as a director in the mid-90s, he contributed his madcap energy to some of the highest grossing movies of the era. Justice, My Foot! (審死官) is very much of the “makes no sense” comedy genre and, directed by Johnnie To for Shaw Brothers, makes great use of the collective propensity for whimsy on offer. Even if not quite managing to keep the momentum going until the closing scenes, Justice, My Foot! succeeds in delivering quick fire (often untranslatable) jokes and period martial arts action sure to keep genre fans happy.

Stephen Chow has always been a force of nature but even before making his name as a director in the mid-90s, he contributed his madcap energy to some of the highest grossing movies of the era. Justice, My Foot! (審死官) is very much of the “makes no sense” comedy genre and, directed by Johnnie To for Shaw Brothers, makes great use of the collective propensity for whimsy on offer. Even if not quite managing to keep the momentum going until the closing scenes, Justice, My Foot! succeeds in delivering quick fire (often untranslatable) jokes and period martial arts action sure to keep genre fans happy. Like many fillmakers of his generation, Kiyoshi Kurosawa began directing commercially in the 1980s working in the pink genre but it was the early ‘90s straight to video boom which provided a career breakthrough. This relatively short lived movement was built on speed where the reliability of the familiar could be harnessed to produce and market low budget genre films with a necessarily high turnover. Kurosawa made his first foray into the V-cinema world in 1994 with the unlikely comedy vehicle Yakuza Taxi (893 タクシー, 893 Taxi). Although Kurosawa had originally accepted the project in the hope of being able to direct a large scale action film, his distaste for the company’s insistence on “jingi” (the yakuza code of honour and humanity) proved something of a barrier but it did, at least, lend free rein to the director’s rather ironic sense of humour.

Like many fillmakers of his generation, Kiyoshi Kurosawa began directing commercially in the 1980s working in the pink genre but it was the early ‘90s straight to video boom which provided a career breakthrough. This relatively short lived movement was built on speed where the reliability of the familiar could be harnessed to produce and market low budget genre films with a necessarily high turnover. Kurosawa made his first foray into the V-cinema world in 1994 with the unlikely comedy vehicle Yakuza Taxi (893 タクシー, 893 Taxi). Although Kurosawa had originally accepted the project in the hope of being able to direct a large scale action film, his distaste for the company’s insistence on “jingi” (the yakuza code of honour and humanity) proved something of a barrier but it did, at least, lend free rein to the director’s rather ironic sense of humour. Hideo Gosha had something of a turbulent career, beginning with a series of films about male chivalry and the way that men work out all their personal issues through violence, but owing to the changing nature of cinematic tastes, he found himself at a loose end towards the end of the ‘70s. Things picked up for him in the ‘80s but the altered times brought with them a slightly different approach as Gosha’s films took on an increasingly female focus in which he reflected on how the themes he explored so fully with his male characters might also affect women. In part prompted by his divorce which apparently gave him the view that women were just as capable of deviousness as men are, and by a renewed relationship with his daughter, Gosha overcame the problem of his chanbara stars ageing beyond his demands of them by allowing his actresses to lead.

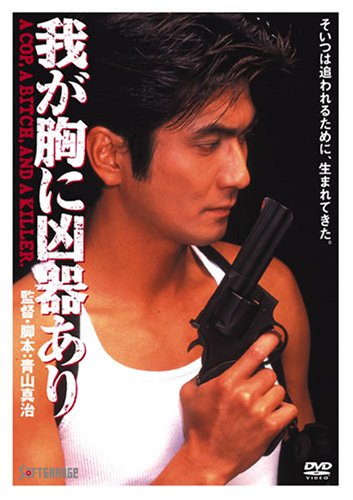

Hideo Gosha had something of a turbulent career, beginning with a series of films about male chivalry and the way that men work out all their personal issues through violence, but owing to the changing nature of cinematic tastes, he found himself at a loose end towards the end of the ‘70s. Things picked up for him in the ‘80s but the altered times brought with them a slightly different approach as Gosha’s films took on an increasingly female focus in which he reflected on how the themes he explored so fully with his male characters might also affect women. In part prompted by his divorce which apparently gave him the view that women were just as capable of deviousness as men are, and by a renewed relationship with his daughter, Gosha overcame the problem of his chanbara stars ageing beyond his demands of them by allowing his actresses to lead. Shinji Aoyama would produce one of the most important Japanese films of the early 21st century in Eureka, but like many directors of his generation he came of age during the V-cinema boom. This relatively short lived medium was the new no holds barred arena for fledgling filmmakers who could adhere to a strict budget and shooting schedule but were also aching to spread their wings. After a short period as an AD with fellow V-cinema director now turned international auteur Kiyoshi Kurosawa, Aoyama directed his first straight to video effort – the sex comedy It’s Not in the Textbook!. Released just after his theatrical debut, Helpless, A Weapon in My Heart (我が胸に凶器あり, Waga Mune ni Kyoki Ari, AKA A Cop, A Bitch, and a Killer) is a more typically genre orientated effort with its cops, robbers, and femme fatale setup but like the best examples of the V-cinema trend it bears the signature of its ambitious director making the most of its humble origins.

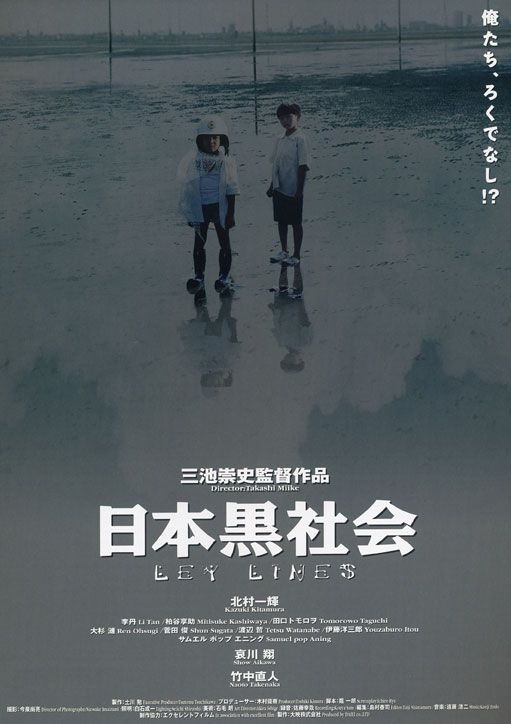

Shinji Aoyama would produce one of the most important Japanese films of the early 21st century in Eureka, but like many directors of his generation he came of age during the V-cinema boom. This relatively short lived medium was the new no holds barred arena for fledgling filmmakers who could adhere to a strict budget and shooting schedule but were also aching to spread their wings. After a short period as an AD with fellow V-cinema director now turned international auteur Kiyoshi Kurosawa, Aoyama directed his first straight to video effort – the sex comedy It’s Not in the Textbook!. Released just after his theatrical debut, Helpless, A Weapon in My Heart (我が胸に凶器あり, Waga Mune ni Kyoki Ari, AKA A Cop, A Bitch, and a Killer) is a more typically genre orientated effort with its cops, robbers, and femme fatale setup but like the best examples of the V-cinema trend it bears the signature of its ambitious director making the most of its humble origins. The three films loosely banded together under the retrospectively applied title of the Black Society Trilogy are not connected in terms of narrative, characters, tone, or location but they do all reflect on attitudes to foreignness, both of a national and of a spiritual kind. Like Tatsuhito in the first film,

The three films loosely banded together under the retrospectively applied title of the Black Society Trilogy are not connected in terms of narrative, characters, tone, or location but they do all reflect on attitudes to foreignness, both of a national and of a spiritual kind. Like Tatsuhito in the first film,