Little Sayuri has had it pretty tough up to now growing up in an orphanage run by Catholic nuns, but her long lost father has finally managed to track her down and she’s going to able to live with her birth family at last! However, on the car ride to her new home her father explains a few things to her to the effect that her mother was involved in some kind of accident and isn’t quite right in the head. Things get weirder when they arrive at the house only to be greated by the guys from the morgue who’ve just arrived to take charge of a maid who’s apparently dropped dead!

Little Sayuri has had it pretty tough up to now growing up in an orphanage run by Catholic nuns, but her long lost father has finally managed to track her down and she’s going to able to live with her birth family at last! However, on the car ride to her new home her father explains a few things to her to the effect that her mother was involved in some kind of accident and isn’t quite right in the head. Things get weirder when they arrive at the house only to be greated by the guys from the morgue who’ve just arrived to take charge of a maid who’s apparently dropped dead!

If that weren’t enough her “mother” calls her by the wrong name and then dad gets a sudden telegram about needing to go to Africa for “several weeks” to study a new kind of snake! On her tour of the house, Sayuri finds a room full of snakes, reptiles and insects (and also for some reason a large vat of acid?!) as well as a room with a buddhist altar where the food seems to disappear just as if Buddha himself were really eating it. Eventually, Sayuri is introduced to her secret sister, Tamami, who has slight facial disfigurement and a wicked disposition which has seen her locked away from view for quite some time…..

Based on the manga by Kazuo Umezu, Snake Girl and the Silver-Haired Witch (蛇娘と白髪魔, Hebi Musume to Hakuhatsuma) is, apparently, aimed at a younger audience which explains its child’s eye view of events but the film makes no concessions to the supposed softness of little minds. With a host of surreal imagery including dream sequences full of creepy, hypnotic spirals, and moments of shocking violence such as a large frog being suddenly ripped in half right in front of Sayuri’s eyes the film certainly doesn’t stint on blood, horror and general freakiness.

Sayuri herself seems largely unperturbed by these strange goings on outside of her nightmarish serpentine visions. She seems to have been well cared for at the orphanage and is happy to have found her family rather than just to be escaping the institution. On getting “home” she does her best to fit in right away, acting politely and trying to bond with her mother even in her confused state. She even tries to get on well with her mysterious sister despite the ominous warning to keep her very existence a secret from her father. Tamami, however, is a nightmare child with homicidal tendencies who isn’t interested in playing happy families with the girl who’s come to usurp her place in the household.

There’s a little more to the set up than just snake based horror (the clue being the Silver-Haired Witch of the title) but the secondary message seems to be one of remembering that the true beauty of a person lies not in their external appearance but in the goodness of their soul. The previously deformed Tamami is later said to be looking sweeter after having “redeemed” herself and Sayuri pledges to honour Tamami’s sisterly sacrifice by always remembering to hold fast and true to the beautiful things in her own soul without being swayed by worldly charms.

Snake Girl and the Silver-Haired Witch is more of a psychological horror tale than some of the effects laden efforts of the period. However, there are a fair few practical effects on show most notably during the dream sequences – one of which sees Sayuri actually fighting a giant snake with a sword, as well as the creepy spirals and the appearance of weird vampire-like snake women, dancing oni masks and the Silver-Haired Witch herself.

A children’s film that no one in their right mind would actually show to a child, Snake Girl and the Silver-Haired Witch is a freakishly psychological horror show seen through the eyes of a little girl. Part dreamscape and part terrifying reality, the film mixes the real and the imagined with a fiendish intensity and it just goes to show that sometimes you really do need to pay attention to the strange fancies of intrepid young ladies.

This trailer doesn’t have any subtitles but it is actually quite scary…..

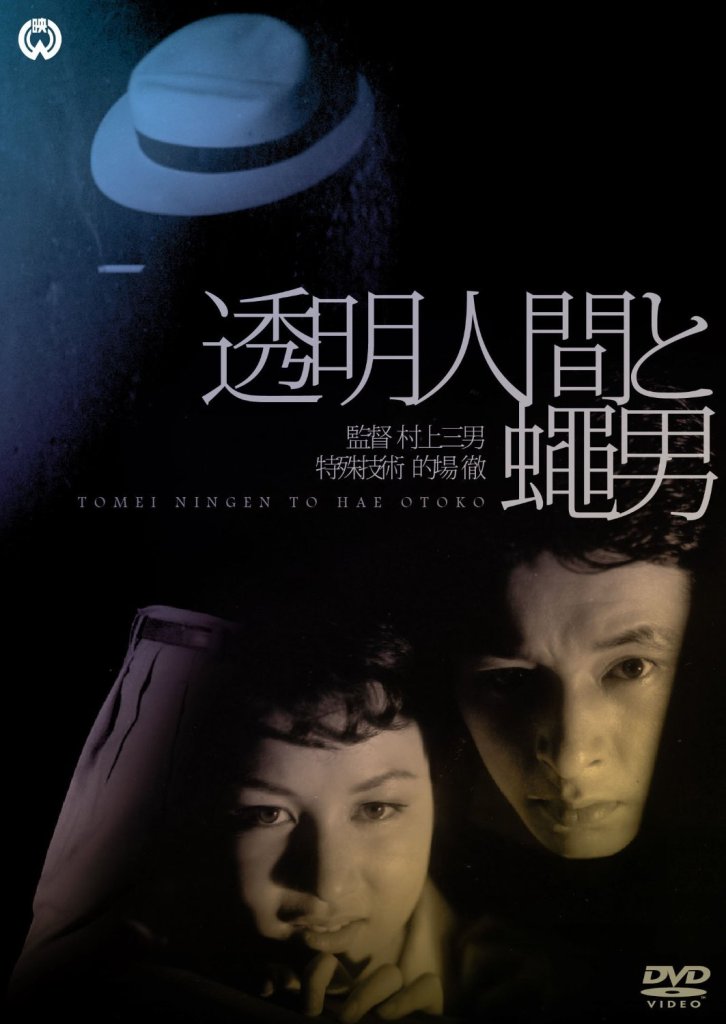

Who would win in a fight between The Invisible Man and The Human Fly? Well, when you think about it, the answer’s sort of obvious and how funny it would be to watch probably depends on your ability to detect the facial expressions of The Human Fly, but nevertheless Daiei managed to make an entire film out of this concept which is a sort of late follow-up to their original take on

Who would win in a fight between The Invisible Man and The Human Fly? Well, when you think about it, the answer’s sort of obvious and how funny it would be to watch probably depends on your ability to detect the facial expressions of The Human Fly, but nevertheless Daiei managed to make an entire film out of this concept which is a sort of late follow-up to their original take on

Released in 1949, The Invisible Man Appears (透明人間現る, Toumei Ningen Arawaru) is the oldest extant Japanese science fiction film. Loosely based on the classic HG Wells story The Invisible Man but taking its cues from the various Hollywood adaptations most prominently the Claude Rains version from 1933, The Invisible Man Appears also adds a hearty dose of moral guidance when it comes to scientific research.

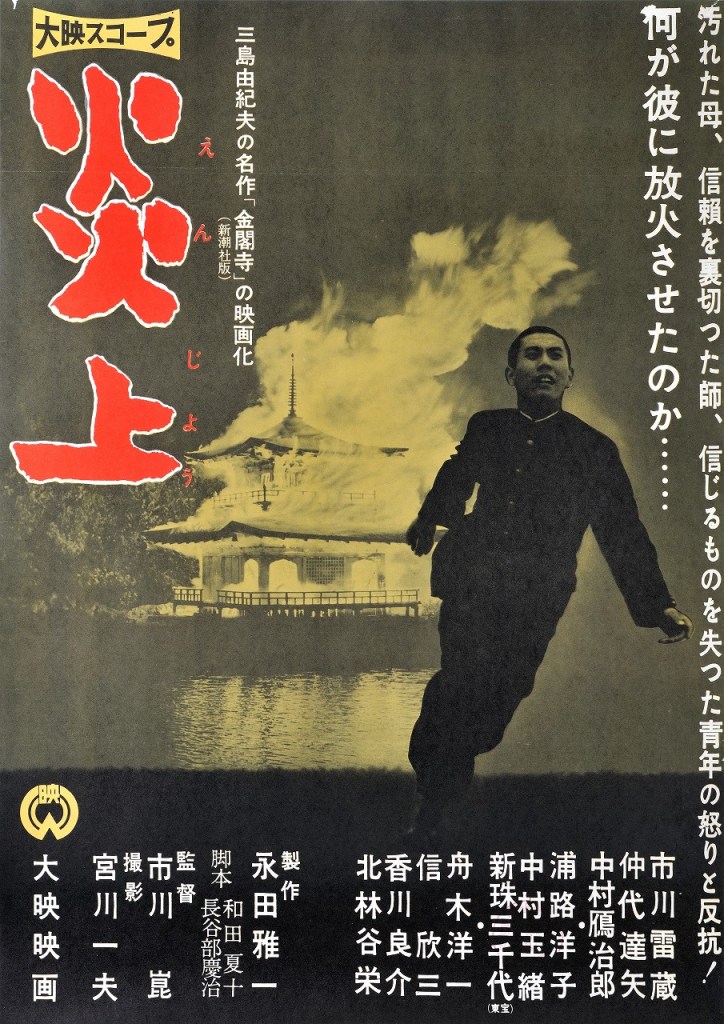

Released in 1949, The Invisible Man Appears (透明人間現る, Toumei Ningen Arawaru) is the oldest extant Japanese science fiction film. Loosely based on the classic HG Wells story The Invisible Man but taking its cues from the various Hollywood adaptations most prominently the Claude Rains version from 1933, The Invisible Man Appears also adds a hearty dose of moral guidance when it comes to scientific research. Kon Ichikawa turns his unflinching eyes to the hypocrisy of the post-war world and its tormented youth in adapting one of Yukio Mishima’s most acclaimed works, The Temple of the Golden Pavilion. Inspired by the real life burning of the Kinkaku-ji temple in 1950 by a “disturbed” monk, Enjo (炎上, AKA Conflagration / Flame of Torment) examines the spiritual and moral disintegration of a young man obsessed with beauty but shunned by society because of a disability.

Kon Ichikawa turns his unflinching eyes to the hypocrisy of the post-war world and its tormented youth in adapting one of Yukio Mishima’s most acclaimed works, The Temple of the Golden Pavilion. Inspired by the real life burning of the Kinkaku-ji temple in 1950 by a “disturbed” monk, Enjo (炎上, AKA Conflagration / Flame of Torment) examines the spiritual and moral disintegration of a young man obsessed with beauty but shunned by society because of a disability.

For arguably his most famous film, 1964’s Manji (卍), Masumura returns to the themes of destructive sexual obsession which recur throughout his career but this time from the slightly more unusual angle of a same sex “romance”. However, this is less a tale of lesbian true love frustrated by social mores than it is a critique of all romantic entanglements which are shown to be intensely selfish and easily manipulated. Based on Tanizaki’s 1930s novel Quicksand, Manji is the tale of four would be lovers who each vie to be sun in this complicated, desire filled galaxy.

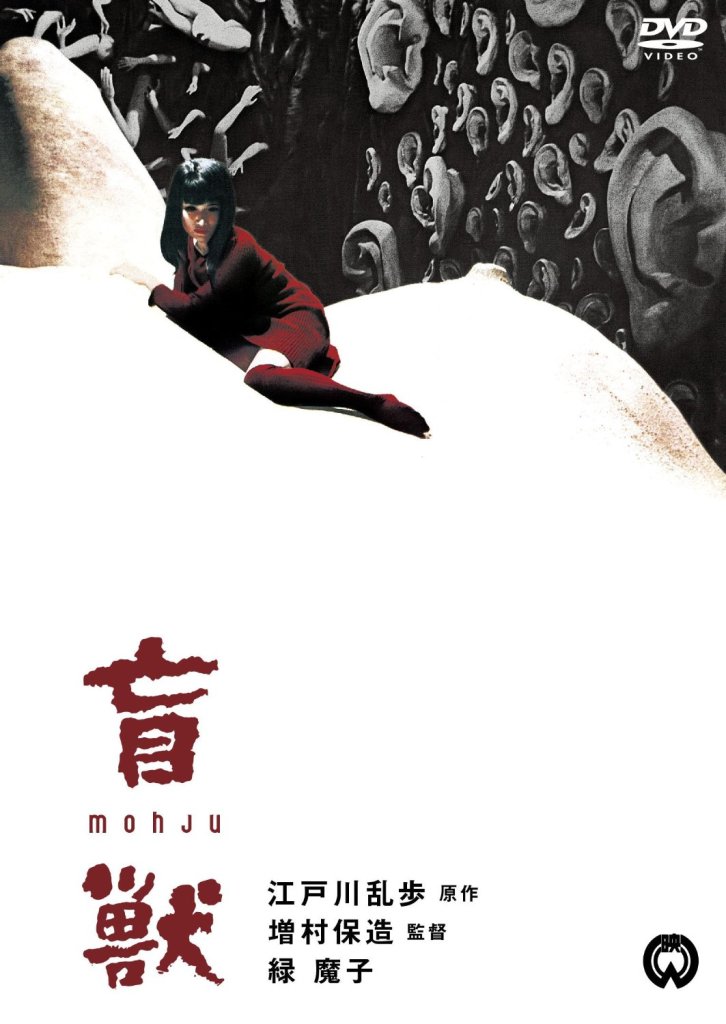

For arguably his most famous film, 1964’s Manji (卍), Masumura returns to the themes of destructive sexual obsession which recur throughout his career but this time from the slightly more unusual angle of a same sex “romance”. However, this is less a tale of lesbian true love frustrated by social mores than it is a critique of all romantic entanglements which are shown to be intensely selfish and easily manipulated. Based on Tanizaki’s 1930s novel Quicksand, Manji is the tale of four would be lovers who each vie to be sun in this complicated, desire filled galaxy. Never one to take his foot off the accelerator, Yazuso Masumura hurtles headlong into the realms of surreal horror with 1969’s Blind Beast (盲獣, Moju). Based on a 1930s serialised novel by Japan’s master of eerie horror, Edogawa Rampo, the film has much more in common with the wilfully overwrought, post gothic European arthouse “horror” movies of period than with the Japanese. Dark, surreal and disturbing, Blind Beast is ultimately much more than the sum of its parts.

Never one to take his foot off the accelerator, Yazuso Masumura hurtles headlong into the realms of surreal horror with 1969’s Blind Beast (盲獣, Moju). Based on a 1930s serialised novel by Japan’s master of eerie horror, Edogawa Rampo, the film has much more in common with the wilfully overwrought, post gothic European arthouse “horror” movies of period than with the Japanese. Dark, surreal and disturbing, Blind Beast is ultimately much more than the sum of its parts. Irezumi (刺青) is one of three films completed by the always prolific Yasuzo Masumura in 1966 alone and, though it stars frequent collaborator Ayako Wakao, couldn’t be more different than the actresses’ other performance for the director that year, the wartime drama

Irezumi (刺青) is one of three films completed by the always prolific Yasuzo Masumura in 1966 alone and, though it stars frequent collaborator Ayako Wakao, couldn’t be more different than the actresses’ other performance for the director that year, the wartime drama  The debut film from Yasuzo Masumura, Kisses (くちづけ, Kuchizuke) takes your typical teen love story but strips it of the nihilism and desperation typical of its era. Much more hopeful in terms of tone than its precursor and genre setter Crazed Fruit, or the even grimmer The Warped Ones, Kisses harks back to the more to wistful French New Wave romance (though predating it ever so slightly) as the two youngsters bond through their mutual misfortunes.

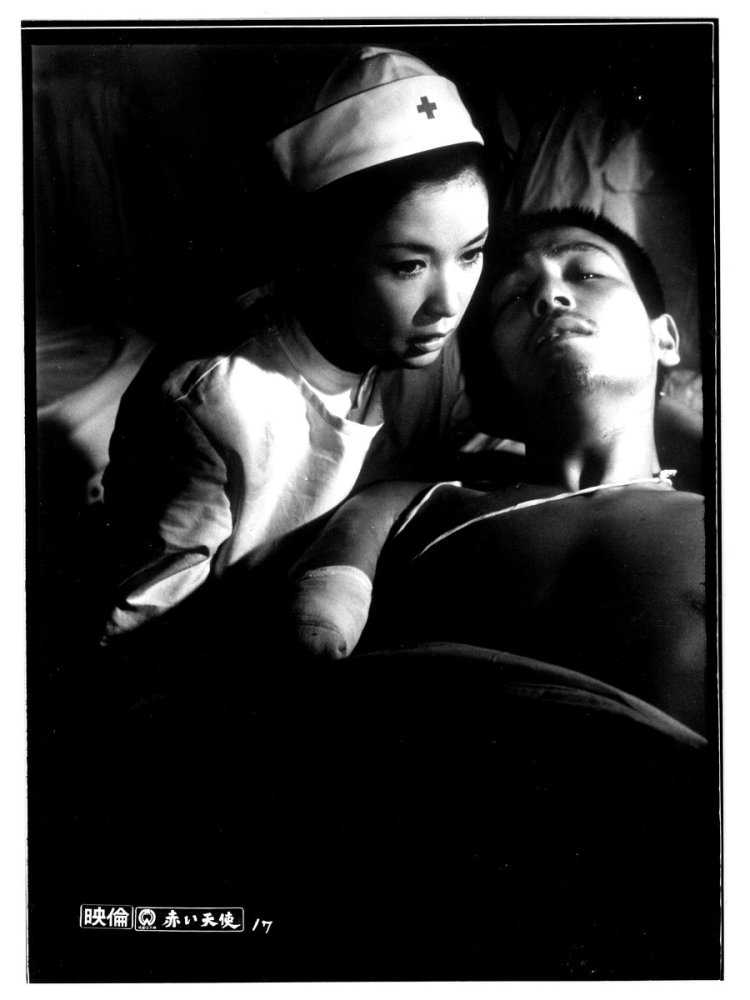

The debut film from Yasuzo Masumura, Kisses (くちづけ, Kuchizuke) takes your typical teen love story but strips it of the nihilism and desperation typical of its era. Much more hopeful in terms of tone than its precursor and genre setter Crazed Fruit, or the even grimmer The Warped Ones, Kisses harks back to the more to wistful French New Wave romance (though predating it ever so slightly) as the two youngsters bond through their mutual misfortunes. Red Angel (赤い天使, Akai Tenshi) sees Masumura returning directly to the theme of the war, and particularly to the early days of the Manchurian campaign. Himself a war veteran (though of a slightly later period), Masumura knew first hand the sheer horror of warfare and with this particular film wanted to convey not just the mangled bodies, blood and destruction that warfare brings about but the secondary effects it has on the psyche of all those connected with it.

Red Angel (赤い天使, Akai Tenshi) sees Masumura returning directly to the theme of the war, and particularly to the early days of the Manchurian campaign. Himself a war veteran (though of a slightly later period), Masumura knew first hand the sheer horror of warfare and with this particular film wanted to convey not just the mangled bodies, blood and destruction that warfare brings about but the secondary effects it has on the psyche of all those connected with it.