Keisuke Kinoshita is often regarded as a sentimentalist but he wasn’t completely immune to bitterness and cynicism as many of his farcical comedies bear out. Danger Stalks Near (風前の灯, Fuzen no Tomoshibi) begins in serious fashion as a trio of young toughs set on burgling the home of an elderly woman they assume has money but quickly descends into absurd dark humour as we discover there’s just as much money-grubbing thievery going on inside the house as out.

Two street toughs bully a nervous young man who needs money to get back to the country into joining them in a plot to rob a suburban house owned by a mean old woman whom they assume must be hiding a serious amount of cash inside. Having watched the place before, they know that it’s generally just housewife Yuriko (Hideko Takamine), her young son Kazuo (Kotohisa Saotome), and grumpy grandma Tetsu (Akiko Tamura) at home during the day after husband Kaneshige (Keiji Sada) has gone to work at his lowly job as a shoe salesman. Today, however, their aspirations towards crime will be thwarted because it’s all go at the Sato residence – flouncing lodgers, sisters with issues, tatami repair men, and mysterious faces from the past all mean that today is a very bad day for burglary but a very good one for entertainment.

Kinoshita deliberately upsets the scene by casting familiar actors Hideko Takamine and Keiji Sada in noticeably deglammed roles – she with a ridiculous pair of large round glasses and he with a giant facial mole designed to make them look “ordinary” but accidentally drawing attention to their star quality in the process. The Satos are, however, a very ordinary family in that they’re intensely obsessed with money and with their own precarious status in the improving but still difficult post-war economy. Tetsu is Kaneshige’s step-mother which is perhaps why he urges his wife to put up with her tyranny seeing as Tetsu is old and will probably not be around much longer, which means it’s just a waiting game until they inherit the house. Whatever else she may be, Tetsu is a mean old woman whose only hobbies are penny pinching and occasional trips to the cinema where she watches heartwarming dramas about filial piety. Her haughty attitude is perhaps why the crooks assume there is cash in the house but sometimes mean people are mean because they really don’t have money rather than just being stingy by nature.

Nevertheless, Tetsu’s iron grip is slowly destroying the family unit. Kaneshige (whose name ironically means “money multiplying” and uses a rather pretentious reading for his name kanji which are often misread by the postman etc) sneaks home to tell his wife he’s won second place in a competition, worrying that if Tetsu finds out she’ll expect her share of the prize money. The old woman is so mean that she even keeps her own stash of eggs in her personal cupboard along with tea for her exclusive use and takes the unusual step of locking the doors when Yuriko is out running errands because she feels “unsafe” in her own home – an ironic state of mind once we discover how exactly Tetsu was able to buy this house as a lonely war widow in the immediate aftermath of the defeat.

Tetsu is, in a fashion, merely protecting her status as matriarch in oppressing daughter-in-law Yuriko by running down her every move as well as those of her sisters whom she criticises for being dull despite their “cheerful” names but also chastises for lack of traditional virtues. Sakura (Toshiko Kobayashi) pays a visit to the Satos because she needs help – her husband has been accused of embezzlement, but is also hoping Yuriko is going to feed her in return for help with domestic tasks only the pair eventually fall out over a missing 30 yen and some crackers. Meanwhile, second sister Ayame (Masako Arisawa) also turns up but with a “friend” (Yoshihide Sato) in tow whom she hopes can become their new lodger after they ended up throwing the old one out because she burned a hole in the tatami mat floor through inattentive use of an iron. Neither Tetsu nor Yuriko could quite get their head around previous tenant Miyoko’s (Hiroko Ito) liberated, student existence of rolling in late after dates and lounging around reading magazines but a male lodger wasn’t something they had in mind either.

Persistent economic stressors have begun to wear away at family bonds – Tetsu is not a nice old woman, but it probably isn’t nice to be living in a house where you know everyone is just waiting for you to die. At least little Kazuo is honest enough to admit he only likes grandma when she gives him candy. Yuriko seems to be a responsible figure for both her sisters, but resents their relying on her for money while enjoying the various gifts they bring to curry favour including a large amount of fish cake from the prospective lodger/Ayame’s intended (if he doesn’t wind up being swayed by the dubious charms of the seductive Miyoko who insists on sitting in her empty room for the rest of the day because she already paid today’s rent). Meanwhile, Yuriko’s attempt to palm off a pair of unwanted tall geta that were a “present” from Kaneshige’s boss (who also heard about the prize money) leads to an accusation of attempted murder as if she hoped Tetsu might topple to her death after trying them on! The burglars have wasted all day sitting outside watching the ridiculous comings and goings as they bide their time waiting to strike only for the police to arrive on a completely unrelated matter. Turns out, inside and outside is not so different as you might think in a society where everything is a transaction and all connection built on mutual resentment.

Titles and opening scene (no subtitles)

In the extreme turbulence of the immediate post-war period, it’s not surprising that Japan looked back to the last time it was confronted with such confusion and upheaval for clues as to how to move forward from its current state of shocked inertia. The heroine of Shiro Toyoda’s adaptation of the

In the extreme turbulence of the immediate post-war period, it’s not surprising that Japan looked back to the last time it was confronted with such confusion and upheaval for clues as to how to move forward from its current state of shocked inertia. The heroine of Shiro Toyoda’s adaptation of the

Hiroshi Shimizu is best remembered for his socially conscious, nuanced character pieces often featuring sympathetic portraits of childhood or the suffering of those who find themselves at the mercy of society’s various prejudices. Nevertheless, as a young director at Shochiku, he too had to cut his teeth on a number of program pictures and this two part novel adaptation is among his earliest. Set in a broadly upper middle class milieu, Seven Seas (七つの海, Nanatsu no Umi) is, perhaps, closer to his real life than many of his subsequent efforts but notably makes class itself a matter for discussion as its wealthy elites wield their privilege like a weapon.

Hiroshi Shimizu is best remembered for his socially conscious, nuanced character pieces often featuring sympathetic portraits of childhood or the suffering of those who find themselves at the mercy of society’s various prejudices. Nevertheless, as a young director at Shochiku, he too had to cut his teeth on a number of program pictures and this two part novel adaptation is among his earliest. Set in a broadly upper middle class milieu, Seven Seas (七つの海, Nanatsu no Umi) is, perhaps, closer to his real life than many of his subsequent efforts but notably makes class itself a matter for discussion as its wealthy elites wield their privilege like a weapon.

Of the chroniclers of the history of post-war Japan, none was perhaps as unflinching as Masaki Kobayashi. However, everyone has to start somewhere and as a junior director at Shochiku where he began as an assistant to Keisuke Kinoshita, Kobayashi was obliged to make his share of regular studio pictures. This was even truer following his attempt at a more personal project –

Of the chroniclers of the history of post-war Japan, none was perhaps as unflinching as Masaki Kobayashi. However, everyone has to start somewhere and as a junior director at Shochiku where he began as an assistant to Keisuke Kinoshita, Kobayashi was obliged to make his share of regular studio pictures. This was even truer following his attempt at a more personal project –  Shochiku was doing pretty well in 1951. Accordingly they could afford to splash out a little in their 30th anniversary year in commissioning the first ever full colour film to be shot in Japan, Carmen Comes Home (カルメン故郷に帰る, Carmen Kokyou ni Kaeru). For this landmark project they chose trusted director Keisuke Kinoshita and opted to use the home grown Fujicolor which has a much more saturated look than the film stocks favoured by overseas studios or those which would become more common in Japan such as Eastman Colour or Agfa. Fujicolour also had a lot of optimum condition requirements including the necessity of shooting outdoors, and so we find ourselves visiting a picturesque mountain village along with a showgirl runaway on her first visit home hoping to show off what a success she’s made for herself in the city.

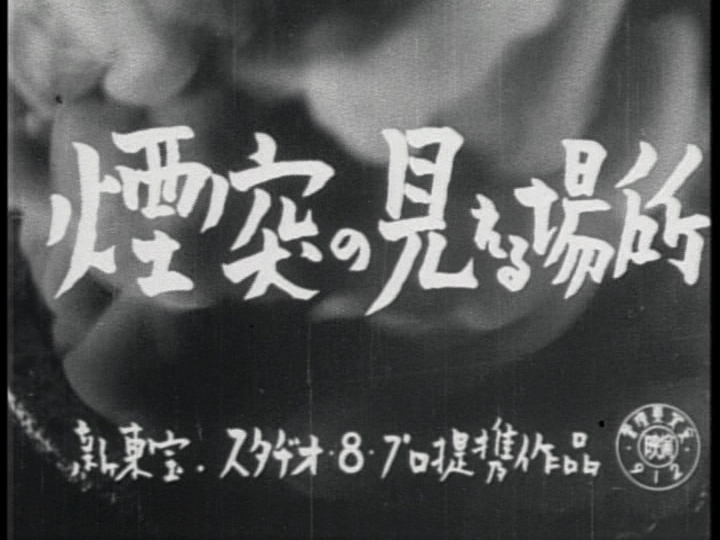

Shochiku was doing pretty well in 1951. Accordingly they could afford to splash out a little in their 30th anniversary year in commissioning the first ever full colour film to be shot in Japan, Carmen Comes Home (カルメン故郷に帰る, Carmen Kokyou ni Kaeru). For this landmark project they chose trusted director Keisuke Kinoshita and opted to use the home grown Fujicolor which has a much more saturated look than the film stocks favoured by overseas studios or those which would become more common in Japan such as Eastman Colour or Agfa. Fujicolour also had a lot of optimum condition requirements including the necessity of shooting outdoors, and so we find ourselves visiting a picturesque mountain village along with a showgirl runaway on her first visit home hoping to show off what a success she’s made for herself in the city. Where Chimneys are Seen (煙突の見える場所, Entotsu no Mieru Basho) is widely regarded as on of the most important films of the immediate post-war era, yet it remains little seen outside of Japan and very little of the work of its director, Heinosuke Gosho, has ever been released in English speaking territories. Like much of Gosho’s filmography, Where Chimneys are Seen devotes itself to exploring the everyday lives of ordinary people, in this case a married couple and their two upstairs lodgers each trying to survive in precarious economic circumstances whilst also coming to terms with the traumatic recent past.

Where Chimneys are Seen (煙突の見える場所, Entotsu no Mieru Basho) is widely regarded as on of the most important films of the immediate post-war era, yet it remains little seen outside of Japan and very little of the work of its director, Heinosuke Gosho, has ever been released in English speaking territories. Like much of Gosho’s filmography, Where Chimneys are Seen devotes itself to exploring the everyday lives of ordinary people, in this case a married couple and their two upstairs lodgers each trying to survive in precarious economic circumstances whilst also coming to terms with the traumatic recent past. Mikio Naruse made the lives of everyday women the central focus of his entire body of work but his 1963 film, A Woman’s Story (女の歴史, Onna no Rekishi), proves one of his less subtle attempts to chart the trials and tribulations of post-war generation. Told largely through extended flashbacks and voice over from Naruse’s frequent leading actress, Hideko Takamine, the film paints a bleak vision of the endless suffering inherent in being a woman at this point in history but does at least offer a glimmer of hope and understanding as the curtains falls.

Mikio Naruse made the lives of everyday women the central focus of his entire body of work but his 1963 film, A Woman’s Story (女の歴史, Onna no Rekishi), proves one of his less subtle attempts to chart the trials and tribulations of post-war generation. Told largely through extended flashbacks and voice over from Naruse’s frequent leading actress, Hideko Takamine, the film paints a bleak vision of the endless suffering inherent in being a woman at this point in history but does at least offer a glimmer of hope and understanding as the curtains falls.