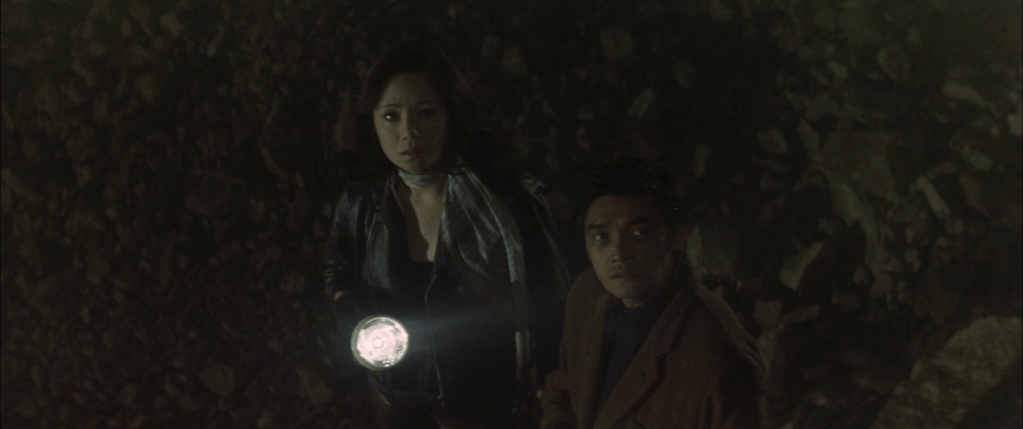

When a lawyer’s wife is found strangled at home, the police immediately arrest a “suspicious person” who is found to be carrying jewellery stolen from her room. Open and shut case, some might say, and prosecutor Ochiai (Keiju Kobayashi) agrees. But in reality nothing is really so black and white in the contemporary society of Hiromichi Horikawa’s crime drama, Pressure of Guilt (白と黒,, Shiro to Kuro). Perhaps ironically, the film opens in the same way as Tai Kato’s later I, the Executioner, with a man’s hands stretching around a piece of rope, and also features a law enforcement officer who is distracted from his duties by a bad case of piles he refuses to get treated.

Ochiai says his haemorrhoids are born of sitting down thinking too much, but the problem might be that he doesn’t think enough or that he suppresses thoughts which might prove inconvenient. There’s something that bothers him about the idea of Wakida (Hisashi Igawa) being the killer, but he shoves his doubts out of his mind and continues questioning him until he confesses. Some of this is born of prejudice. Wakida has a long criminal record mainly for burglary, and has been in and out of prison the whole of his adult life. Currently suffering from TB, he appears to be one of the young men who came to the city in search of work but found only exploitation and eventually had no option but to turn to crime. That he stole the jewellery is not in dispute, but Wakida continues to insist he didn’t kill Mrs Munakata (Koreya Senda). His lack of cooperation puzzles Ochiai, but it confuses him still more that Wakida keeps changing his story. He is, it seems, trying to tell him what he wants to hear, but finally becomes fed up with the whole thing after receiving a letter from his mother telling him to confess. She evidently thinks he did it too. Falling into hopelessness, Wakida declares that he no longer cares who did it and might as well be him because his life is essentially already over. In his condition he won’t last long in prison. There’s no prospect of turning his life around, either. So a death sentence won’t make any difference.

The funny thing is that it’s realising his fiancée must have figured out he did because she’s covering up for him that forces Hamano (Tatsuya Nakadai) into a confession. He’s plagued by guilt that Wakida might die for his crime, but not enough to exonerate him by coming forward. Nevertheless, he tries to talk Wakida round, asking why he confessed and if he was pressured by the prosecutors. The Japanese legal system places confessions above all else, but the issue is that Wakida’s confession is the only evidence that links him to the murder. Just because he stole the jewellery doesn’t mean he killed Mrs Munakata. Ironically enough, he’s defended by the victim’s husband (Koreya Senda), an anti-death penalty activist lawyer who agrees to represent him in part to vindicate his principles. Wakida only agrees to cooperate with Munakata and Hamano who is acting as his assistant when he confirms they’re not trying to help out of pity but only for their own self-interest.

Yet Ochiai might have a point asking why Hamano is certain that Wakida didn’t do it, or why, on beginning to suspect him, he’s trying so hard to exonerate a man who was going to pay for his crime. It’s Hamano’s own suspiciousness that leads him to question his judgement about Wakida and ask himself if his thinking wasn’t too black and white and he should have investigated more thoroughly rather than pressuring Wakida into a confession and charging him. On realising he may have made a mistake, Ochiai puts the prosecution in a difficult position as his boss warns him of the potential reputational damage to the police and prosecutors if they’re shown to have made a mistake with the mild implication that, as he had assumed someone in Hamano’s position would want to, he should just keep quiet and let Wakida hang.

Surprisingly, however, it only seems to improve the public’s view of the prosecution to be able to see them admit that they made a mistake and try to fix it rather than refuse to change their position. Mystery writer Seicho Matsumoto makes a cameo appearance as a TV pundit who says he admires Ochiai, while the film also uses a real TV show host to interview Ochiai boosting the sense of realism. As it turns out, there was more to the story than even Ochiai or Hamano thought, but still he declares that it’s better to be a fool than a hopeless idiot and that he was right to look for the truth even if it ended up biting him in the behind. The pressure of Hamano’s guilt, however, never really dissipates even as he struggles with himself, trying to find a way to save Wakida and avoid becoming a murderer twice over, without giving himself away. Nothing’s really that black and white after all, and this case wasn’t exactly open and shut, but the conviction that it had to be based on prejudice and circumstantial evidence might be the biggest crime at all no matter how it actually turned out.