Kei Kumai’s three-hour epic of human engineering The Sands of Kurobe (黒部の太陽, Kurobe no Taiyo) opens with a titlecard to the effect that the film testifies to the courage of the Japanese people who brought the nation back to life after the war. Partly produced by Kansai Electric Power along with the production agencies of stars Toshiro Mifune and Yujiro Ishihara, the film is therefore somewhat conflicted, part bombastic celebration of Japanese engineering skill and ambivalent critique of the wilful decision to place success above all else including the welfare and safety of ordinary workers.

This critique is most evident to the flashbacks to the construction of Kuro 3 in 1938 which as many point out was conducted by the military under brutal and primitive conditions. The construction of the new Kurobe hydroelectric dam, by contrast, is a much more modern, enlightened affair in which workers have proper equipment and are not simply hacking at rocks with pickaxes wearing only a vest. But then as the conflicted Takeshi (Yujiro Ishihara) points out, it’s all effectively the same. Just because no one is pointing a gun at their heads, it doesn’t mean the men actually building the dam aren’t being exploited rather simply pressured by a vague notion of national good that they should be ready to lay down their lives. Could it be that “prosperity” is worse thing to die for than “patriotism”, especially when it appears as if your employer cares little for your physical wealth and economic wellbeing simply pledging that they will support the families of men killed during the dam’s construction.

That there will be deaths seems inevitable. The man placed in charge of building a tunnel through the mountain, Kitagawa (Toshiro Mifune), is haunted by the vision of a man falling from a cliff that he witnessed when they first hiked to the dam site. He originally described the project as “crazy” and wanted to resign but was convinced to stay on. Kitagawa is himself fond of insisting on safety first where others are minded to cut corners, but also troubled by domestic issues in the film’s sometimes insensitive use of his daughter’s terminal leukaemia as a mirror for the dam project in considering what is and isn’t possible through human endeavour. The suggestion is that Kitagawa wants to believe the miracle of the dam is possible because needs to keep believing in a scientific miracle that can save his daughter, though obviously even if it is ultimately possible to build this dam that’s designed to fuel the post-war rocket to economic prosperity there are limits and unfortunately decades later we have still not found a cure for cancer though treatment may be more effective.

Takeshi meanwhile has a similar battle with his hard-nosed father whose devotion to the dam project he describes almost like an addiction, suggesting that he values nothing outside of tunnelling and is willing to sacrifice everything in its name including the lives of himself and others. A flashback to to 1938 reveals that he asked his own teenage son to place dynamite and inadvertently caused his death though lax safety procedures which is the understandable reason why his wife eventually left him taking Takeshi with her. But the strange thing is for all his original opposition, Takeshi too is later captivated by the immensity of the challenge if also wary that the workers are falling victim to the same sickness as his father and are still being exploited by those like him who expect them to offer up their lives while paying them a pittance and complaining when the project does not proceed along their schedule.

The almost nationalistic, bombastic quality of the film seems at odds with some of Kumai’s previous work save the discussion of the building of the 1938 tunnel though this largely serves as a contrast to imply that this time is different because they’re doing it for love of country rather the forced patriotism of the militarist past. Kitagawa justifies himself that if they don’t build the dam, economic prosperity will stall, companies will go bust, and people will lose their jobs but it seems somewhat hollow in the knowledge many men are certain to die while building this dam. Kumai undercuts the bombast with a series of scenes shot like a disaster movie in which supports collapse and the tunnel floods, or men are hit by falling rocks, eventually closing on an ironic Soviet-style statue dedicated to the labour of the workers that seems to question the immense loss of life along with the destruction of the natural beauty of Mount Kurobe but cannot in the end fully reconcile himself, torn between a celebration of human endeavour and its equally human costs.

Original trailer (no subtitles)

Ah, youth. It explains so many things though, sadly, only long after it’s passed. For the young men who had the misfortune to come of age in the 1930s, their glory days are filled with bittersweet memories as their personal development occurred against a backdrop of increasing political division. Seijun Suzuki was not exactly apolitical in his filmmaking despite his reputation for “nonsense”, but in Fighting Elegy (けんかえれじい, Kenka Elegy) he turns a wry eye back to his contemporaries for a rueful exploration of militarism’s appeal to the angry young man. When emotion must be sublimated and desire repressed, all that youthful energy has to go somewhere and so the unresolved tensions of the young men of Japan brought about an unwelcome revolution in a misguided attempt at mastery over the self.

Ah, youth. It explains so many things though, sadly, only long after it’s passed. For the young men who had the misfortune to come of age in the 1930s, their glory days are filled with bittersweet memories as their personal development occurred against a backdrop of increasing political division. Seijun Suzuki was not exactly apolitical in his filmmaking despite his reputation for “nonsense”, but in Fighting Elegy (けんかえれじい, Kenka Elegy) he turns a wry eye back to his contemporaries for a rueful exploration of militarism’s appeal to the angry young man. When emotion must be sublimated and desire repressed, all that youthful energy has to go somewhere and so the unresolved tensions of the young men of Japan brought about an unwelcome revolution in a misguided attempt at mastery over the self. Things take a slight detour in the third of the Outlaw series this time titled “Heartless” (大幹部 無頼非情, Daikanbu Burai Hijo). Rather than picking up where we left Goro – collapsed on a high school volleyball court, it’s now 1956 and we’re with a guy called “Goro the Assassin” but it’s not exactly clear is this is a side story or perhaps an entirely different continuity for the story of the noble hearted gangster we’ve been following so far. The only constant is actor Tetsuya Watari who once again plays Goro Fujikawa but in an even more confusing touch the supporting characters are played by many of the actors who featured in the first two films but are actually playing entirely different people….

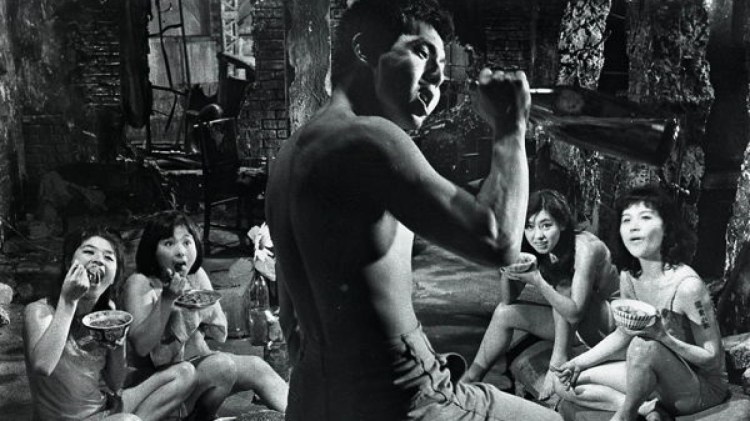

Things take a slight detour in the third of the Outlaw series this time titled “Heartless” (大幹部 無頼非情, Daikanbu Burai Hijo). Rather than picking up where we left Goro – collapsed on a high school volleyball court, it’s now 1956 and we’re with a guy called “Goro the Assassin” but it’s not exactly clear is this is a side story or perhaps an entirely different continuity for the story of the noble hearted gangster we’ve been following so far. The only constant is actor Tetsuya Watari who once again plays Goro Fujikawa but in an even more confusing touch the supporting characters are played by many of the actors who featured in the first two films but are actually playing entirely different people…. What are you supposed to do when you’ve lost a war? Your former enemies all around you, refusing to help no matter what they say and there are only black-marketers and gangsters where there used to be merchants and craftsmen. Everyone is looking out for themselves, everyone is in the gutter. How are you supposed to build anything out of this chaos? Perhaps you aren’t, but you have to go one living, somehow. The picture of the immediate post-war world which Suzuki paints in Gate of Flesh (肉体の門, Nikutai no Mon) is fairly hellish – crowded, smelly marketplaces thronging with desperate people. Based on a novel by Taijiro Tamura (who also provided the source material for Suzuki’s Story of a Prostitute), Gate of Flesh has its lens firmly pointed at the bottom of the heap and resolutely refuses to avert its gaze.

What are you supposed to do when you’ve lost a war? Your former enemies all around you, refusing to help no matter what they say and there are only black-marketers and gangsters where there used to be merchants and craftsmen. Everyone is looking out for themselves, everyone is in the gutter. How are you supposed to build anything out of this chaos? Perhaps you aren’t, but you have to go one living, somehow. The picture of the immediate post-war world which Suzuki paints in Gate of Flesh (肉体の門, Nikutai no Mon) is fairly hellish – crowded, smelly marketplaces thronging with desperate people. Based on a novel by Taijiro Tamura (who also provided the source material for Suzuki’s Story of a Prostitute), Gate of Flesh has its lens firmly pointed at the bottom of the heap and resolutely refuses to avert its gaze.