Yasuzo Masumura is best remembered for his deliberately transgressive, often shockingly grotesque critiques of Japanese society and its conformist overtones. Lullaby of the Earth (大地の子守歌, Daichi no Komoriuta) is one of his few completely independent features, filmed after the bankruptcy of Daiei where Masumura had spent the bulk of his early years. As such, it is quite an exception in terms of his wider career both in terms of its production and in its earthy, spiritual themes. Adapted from the 1974 novel by Kukiko Moto, Lullaby of the Earth is the story of an abandoned and betrayed woman but one who also draws her strength from the Earth itself.

Yasuzo Masumura is best remembered for his deliberately transgressive, often shockingly grotesque critiques of Japanese society and its conformist overtones. Lullaby of the Earth (大地の子守歌, Daichi no Komoriuta) is one of his few completely independent features, filmed after the bankruptcy of Daiei where Masumura had spent the bulk of his early years. As such, it is quite an exception in terms of his wider career both in terms of its production and in its earthy, spiritual themes. Adapted from the 1974 novel by Kukiko Moto, Lullaby of the Earth is the story of an abandoned and betrayed woman but one who also draws her strength from the Earth itself.

13 year old Rin (Mieko Harada) has been living with her adopted grandmother in a remote mountain community. Returning home one day triumphantly carrying a rabbit for dinner, Rin discovers that her grandmother has passed away. Being just a child and now alone and frightened, Rin does not know what to do and later receives harsh treatment from the villagers from whom she temporarily conceals her grandmother’s death. With no one to look after her, Rin is approached by a kind seeming man in Western dress who offers her a good job on a nearby island which, he says, pays well and offers a much better quality of life than Rin’s current survivalist setup in the mountains. Rin has heard tales of men like him before and is not taken in by his arguments, even when he suggests she could use the money to buy a proper grave for her grandmother. She is, however, caught when he mentions taking her to see the sea – something she has been longing for for most of her life.

However, Rin’s pure joy at the waves and endless horizons of the shoreline is short lived when reality hits home and she realises she has been sold to a brothel. The brothel owners are not a bad sort, considering, and intend on using her as a servant until she comes of age but Rin is not having any of it. Refusing to eat, work, or wear her new clothes, Rin is proving to be a very bad investment but changes her tune when she strikes up a friendship with a girl who works at a local store who convinces her that her rebellion is misplaced. Work hard and pay off your debt, she says, and they’ll let you go home. Rin decides to do just that, and with her characteristic energy, but her journey home is not to be such a straight forward experience.

Lullaby of the Earth maybe unusual in Masumura’s filmography due its period setting and gentler, more spiritually orientated progression but Rin is, in many ways, a typical Masumura heroine. A true child of nature, Rin is athletic, at home in the forests and woods trapping rabbits and building fires. Her downfall is brought about precisely because of her desire for total freedom. Longing to see the sea with all of the freedom and possibilities that it suggests, Rin allows herself to be taken in by the false promises of a procurer (presumably alerted by a less than helpful villager), little knowing that she’s damned herself for a period of at least three years.

Made to suffer numerous degradations from the humiliation of her servitude, to a beating that leaves her half dead and her final forced prostitution, Rin maintains her resistance in whichever way she can. Striving for control, Rin takes on a masculine quality defined by strength and agility rather than elegance and beauty. Once again longing for the sea, Rin begs to be allowed to row the boat that takes the girls out to find business from passing ships. “If you take my oar you’ll be in trouble” she later exclaims, clinging to her source of male power even whilst being forced into the gaudy brothel kimono. Displaying her own ability for active choice even within her controlled environment, Rin takes the scissors to her own hair, cutting it short like a man’s.

Given the chance to escape the brothel for a comfortable life as the mistress of a wealthy man, Rin refuses. A decision which seems bizarre to many of the other girls, but Rin will have her freedom back in its entirety – she will not swap one cage for another as the prized possession of a some other authority. Meeting a man who claims he may be able to help her, Rin starts working overtime to save the money to escape with the consequence that her health suffers, leading to almost total blindness followed by listless depression. Only at this point does her inner fire start to waver, but it is never extinguished allowing her to finally make a break for it even if she literally cannot see where she is headed.

Rin’s guiding voices come from the Earth itself as mediated by the kindly internal presence of her grandmother. The soil is sacred, as her grandmother told her. Rub soil into your wounds and you’ll soon be healed. In times of trouble, lie against the Earth’s surface and you will know what to do. Rin wants to find the way back to her mountain, but it may no longer exist for her. Nevertheless, the Earth itself is singing and will tell her where to go, so long as she can find the strength to listen.

Masumura begins the film with Rin at prayer, dressed in the white clothes of a pilgrim and dutifully following the temple paths around the island of Shikoku. Suffering a final PTSD flashback of all she’s suffered since her grandmother’s passing, Rin is once again comforted by the sounds of the Earth, beginning with her grandmother’s voice to which more are slowly added, cheering her on with chorus of support as she walks towards the end of her journey. A wonderful, early leading performance for Mieko Harada, Lullaby of the Earth is a far more new age exercise than Masumura’s generally cynical approach to human spirituality would usually allow but neatly tallies with his primary concerns in its heroine’s eternal quest for her own autonomy, body and soul, as she traverses a cold and unforgiving world.

Prolific as he is, veteran director Yoji Yamada (or perhaps his frequent screenwriter in recent years Emiko Hiramatsu) clearly takes pleasure in selecting film titles but What a Wonderful Family! (家族はつらいよ, Kazoku wa Tsurai yo) takes things one step further by referencing Yamada’s own long running film series Otoko wa Tsurai yo (better known as Tora-san). Stepping back into the realms of comedy, Yamada brings a little of that Tora-san warmth with him for a wry look at the contemporary Japanese family with all of its classic and universal aspects both good and bad even as it finds itself undergoing number of social changes.

Prolific as he is, veteran director Yoji Yamada (or perhaps his frequent screenwriter in recent years Emiko Hiramatsu) clearly takes pleasure in selecting film titles but What a Wonderful Family! (家族はつらいよ, Kazoku wa Tsurai yo) takes things one step further by referencing Yamada’s own long running film series Otoko wa Tsurai yo (better known as Tora-san). Stepping back into the realms of comedy, Yamada brings a little of that Tora-san warmth with him for a wry look at the contemporary Japanese family with all of its classic and universal aspects both good and bad even as it finds itself undergoing number of social changes. It would be a mistake to say that Hiroshi Shimizu made “children’s films” in that his work is not particularly intended for younger audiences though it often takes their point of view. This is certainly true of one of his most well known pieces, Children in the Wind (風の中の子供, Kaze no Naka no Kodomo), which is told entirely from the perspective of the two young boys who suddenly find themselves thrown into an entirely different world when their father is framed for embezzlement and arrested. Encompassing Shimizu’s constant themes of injustice, compassion and resilience, Children in the Wind is one of his kindest films, if perhaps one of his lightest.

It would be a mistake to say that Hiroshi Shimizu made “children’s films” in that his work is not particularly intended for younger audiences though it often takes their point of view. This is certainly true of one of his most well known pieces, Children in the Wind (風の中の子供, Kaze no Naka no Kodomo), which is told entirely from the perspective of the two young boys who suddenly find themselves thrown into an entirely different world when their father is framed for embezzlement and arrested. Encompassing Shimizu’s constant themes of injustice, compassion and resilience, Children in the Wind is one of his kindest films, if perhaps one of his lightest. Yoshimitsu Morita is an enigma. While directing some of the most acclaimed Japanese films of the 80s including

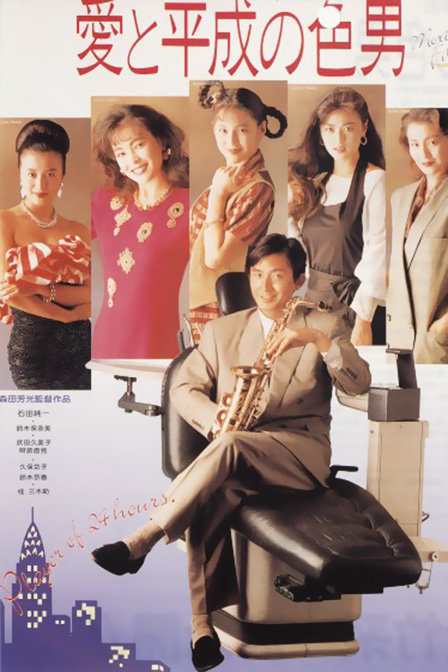

Yoshimitsu Morita is an enigma. While directing some of the most acclaimed Japanese films of the 80s including  History marches on, and humanity keeps pace with it. Life on the periphery is no less important than at the centre, but those on the edges are often eclipsed when “great” men and women come along. So it is for the long suffering Tose (Chikage Awashima), the put upon heroine of Heinosuke Gosho’s jidaigeki The Fireflies (螢火, Hotarubi). An inn keeper in the turbulent period marking the end of the Tokugawa shogunate and with it centuries of self imposed isolation, Tose is just one of the ordinary people living through extraordinary times but unlike most her independent spirit sparks brightly even through her continuing strife.

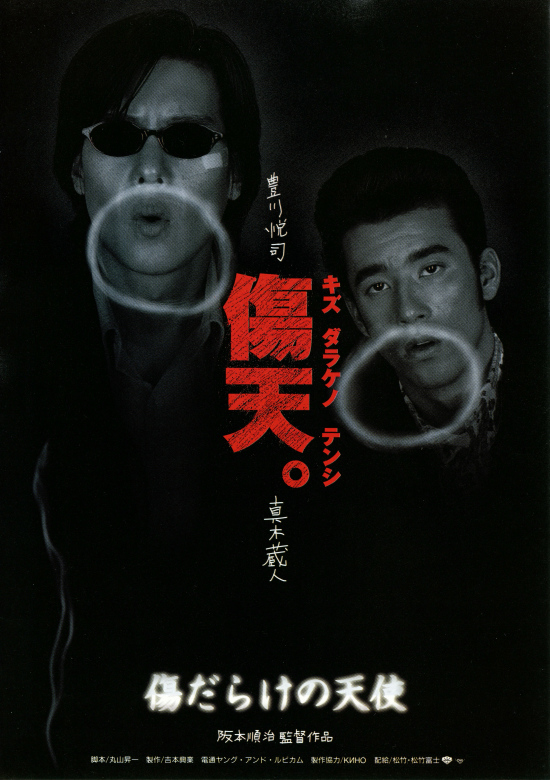

History marches on, and humanity keeps pace with it. Life on the periphery is no less important than at the centre, but those on the edges are often eclipsed when “great” men and women come along. So it is for the long suffering Tose (Chikage Awashima), the put upon heroine of Heinosuke Gosho’s jidaigeki The Fireflies (螢火, Hotarubi). An inn keeper in the turbulent period marking the end of the Tokugawa shogunate and with it centuries of self imposed isolation, Tose is just one of the ordinary people living through extraordinary times but unlike most her independent spirit sparks brightly even through her continuing strife. Despite having started his career in the action field with the boxing film Dotsuitarunen and an entry in the New Battles Without Honour and Humanity series, Junji Sakamoto has increasingly moved into gentler, socially conscious films including the Thai set Children of the Dark and the Toei 60th Anniversary prestige picture

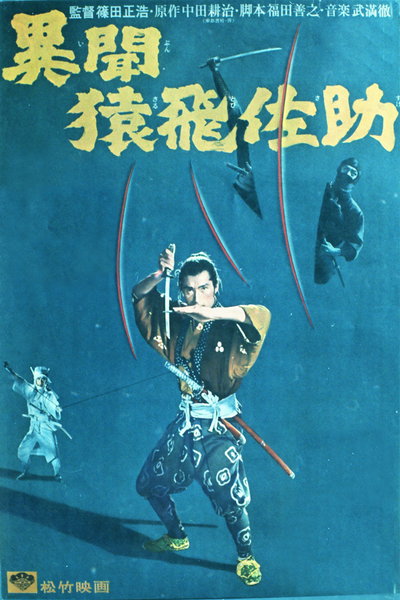

Despite having started his career in the action field with the boxing film Dotsuitarunen and an entry in the New Battles Without Honour and Humanity series, Junji Sakamoto has increasingly moved into gentler, socially conscious films including the Thai set Children of the Dark and the Toei 60th Anniversary prestige picture  Nothing is certain these days, so say the protagonists at the centre of Masahiro Shinoda’s whirlwind of intrigue, Samurai Spy (異聞猿飛佐助, Ibun Sarutobi Sasuke). Set 14 years after the battle of Sekigahara which ushered in a long period of peace under the banner of the Tokugawa Shogunate, Samurai Spy effectively imports its contemporary cold war atmosphere to feudal Japan in which warring states continue to vie for power through the use of covert spy networks run from Edo and Osaka respectively. Sides are switched, friends are betrayed, innocents are murdered. The peace is fragile, but is it worth preserving even at such mounting cost?

Nothing is certain these days, so say the protagonists at the centre of Masahiro Shinoda’s whirlwind of intrigue, Samurai Spy (異聞猿飛佐助, Ibun Sarutobi Sasuke). Set 14 years after the battle of Sekigahara which ushered in a long period of peace under the banner of the Tokugawa Shogunate, Samurai Spy effectively imports its contemporary cold war atmosphere to feudal Japan in which warring states continue to vie for power through the use of covert spy networks run from Edo and Osaka respectively. Sides are switched, friends are betrayed, innocents are murdered. The peace is fragile, but is it worth preserving even at such mounting cost? How well do you know your neighbours? Perhaps you have one that seems a little bit strange to you, “creepy”, even. Then again, everyone has their quirks, so you leave things at nodding at your “probably harmless” fellow suburbanites and walking away as quickly as possible. The central couple at the centre of Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s return to genre filmmaking Creepy (クリーピー 偽りの隣人, Creepy Itsuwari no Rinjin), based on the novel by Yutaka Maekawa, may have wished they’d better heeded their initial instincts when it comes to dealing with their decidedly odd new neighbours considering the extremely dark territory they’re about to move in to…

How well do you know your neighbours? Perhaps you have one that seems a little bit strange to you, “creepy”, even. Then again, everyone has their quirks, so you leave things at nodding at your “probably harmless” fellow suburbanites and walking away as quickly as possible. The central couple at the centre of Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s return to genre filmmaking Creepy (クリーピー 偽りの隣人, Creepy Itsuwari no Rinjin), based on the novel by Yutaka Maekawa, may have wished they’d better heeded their initial instincts when it comes to dealing with their decidedly odd new neighbours considering the extremely dark territory they’re about to move in to…

Nobuhiko Obayashi is no stranger to a ghost story whether literal or figural but never has his pre-occupation with being pre-occupied about the past been more delicately expressed than in his 1988 horror-tinged supernatural adventure, The Discarnates (異人たちとの夏, Ijintachi to no Natsu). Nostalgia is a central pillar of Obayashi’s world, as drenched in melancholy as it often is, but it can also be pernicious – an anchor which pins a person in a certain spot and forever impedes their progress.

Nobuhiko Obayashi is no stranger to a ghost story whether literal or figural but never has his pre-occupation with being pre-occupied about the past been more delicately expressed than in his 1988 horror-tinged supernatural adventure, The Discarnates (異人たちとの夏, Ijintachi to no Natsu). Nostalgia is a central pillar of Obayashi’s world, as drenched in melancholy as it often is, but it can also be pernicious – an anchor which pins a person in a certain spot and forever impedes their progress.