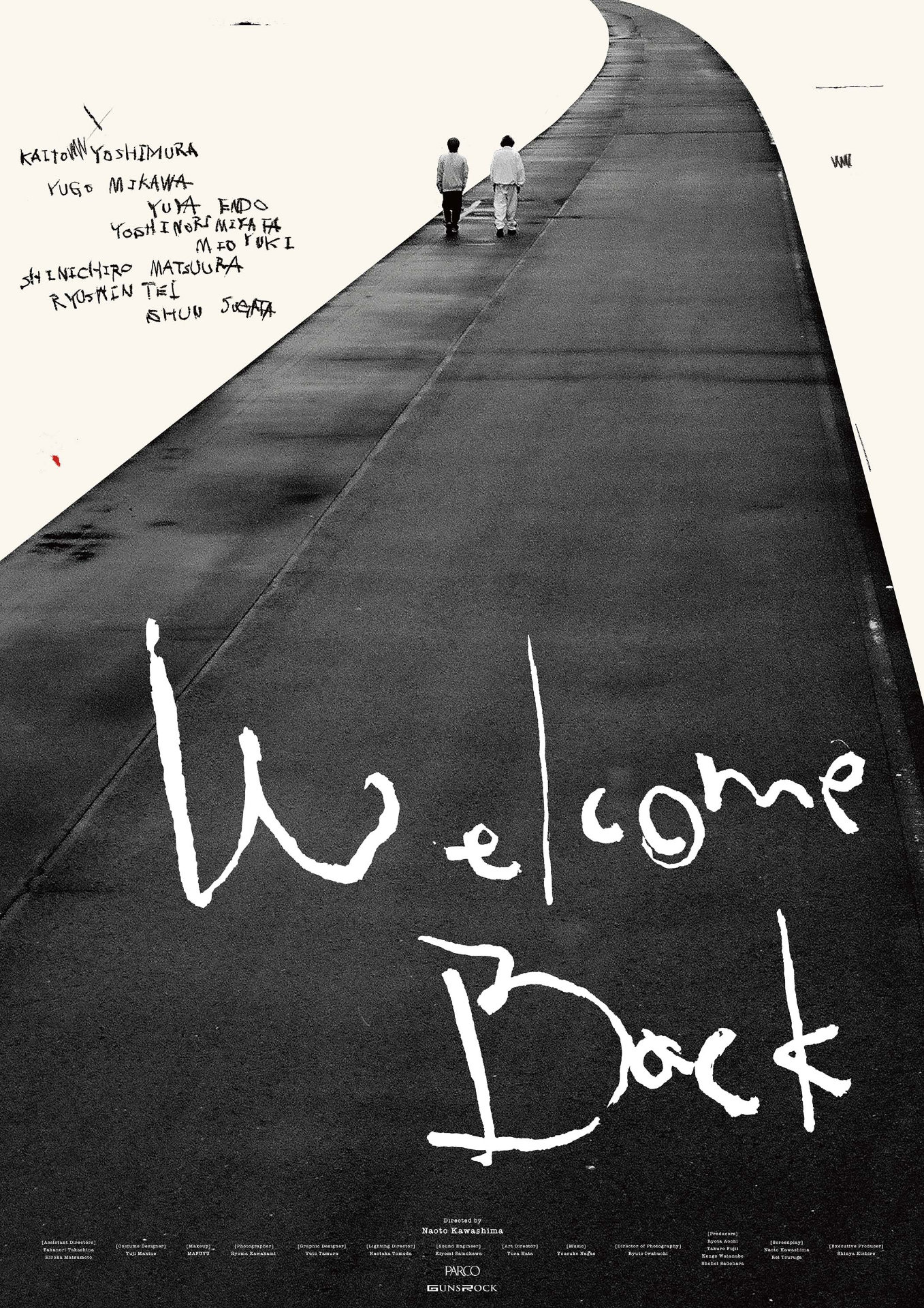

“Once you play the heel, you can’t go back,” according to up-and-coming boxer Teru’s (Kaito Yoshimura) coach, but it turns out to be truer than for most for the aspiring champion for whom getting up off the mat proves an act of impossibility. While he plays the hero for younger brother figure Ben (Yugo Mikawa) and talks a big game before stepping into the ring, in reality Teru is riddled with insecurity and using bluster to overcome the fear that he can’t live up to the image Ben has of him.

The terrible thing is, he might be right and Ben, a young man with learning difficulties who later gives his age as 10 though clearly in his 20s, may be beginning to see through him. “I lost because I looked at you,” he later says of a failed attempt to fight off their chief rival, but it might as well go for his life which he’s spent in Teru’s footsteps ever since his mother abandoned him with Teru’s family when they were just children on the same housing estate.

As such, Teru does genuinely care for Ben, but has also been hiding behind him in allowing him to become something like a mascot or cheerleader, someone over whom he feels superior but also looks up to him as the sort of person he wants to be but perhaps isn’t. In any case, his boxing career has been going well and he’s on track to become the Japanese champion, but at the same time he’s proud and arrogant. He thinks he knows better than his coach, and likes to make a big entrance trash talking his opponents in a larger-than-life manner that might be more suited to pro-wrestling than the comparatively more earnest world of boxing and earns him a degree of suspicion as a result. His opponent Kitazawa (Yoshinori Miyata) is his opposite number in that, as Teru points out, he’s deathly serious and certain in his abilities which is why he’s able to KO Teru mere seconds into their title match. No longer “undefeated”, Teru simply gives up and retires from boxing only to spiral downward while working as a supermarket mascot, eg. Ben’s old job from which he also gets him fired by messing it up for both of them because of his pride and temper.

But for Ben, the certain truth of his life has been that “Teru never loses”. Now that Teru lost, something’s very wrong with the universe and he has to put it right, which is why he decides to fight Kitazawa himself even if he has to walk to Osaka from Tokyo to do it because they’ve got no money for transport. What neither Teru nor Aoyama (Yuya Endo), a boxer Teru once defeated in another title fight but ends up helping him and Ben on their quest, is that after obsessively watching Teru all this time, Ben is actually quite a talented, if untrained, fighter. They were hoping they could get him to give up on his plan by finding someone weaker than Kitazawa to defeat him so he’d know he had no chance, but he basically fights his way all across Japan to prove that Teru really is the hero he always thought him to be.

This turns out to be inconvenient for Teru because inside he feels himself to be a loser and since his single defeat has been running away from the fight. As he later begrudgingly realises, none of this would be happening if he’d knuckled down done the training so he’d be able to beat Kitazawa in the first place rather than being consumed by his pride and arrogance. He should be the one fighting Kitazawa, not Ben who is putting himself in danger because the world doesn’t make sense to him any more. Kitazawa, meanwhile, has his number and seems to look down on him for his lack of fighting spirit, correctly surmising he will walk away from the chance to fight him for real when he opts for a last resort of trying to bribe him to fake a sparring match so that Ben will see him win and be able to go on with his life.

But nothing quite goes to plan, and it seems like Ben might be starting to see that Teru might actually be using him to bolster his own sense of low self-esteem which obviously means that he does and always has looked down on Ben. Having come to a realisation that he needed to play the role of the hero that Ben needed him to be, perhaps what he sees is that Ben has outgrown him and that despite his constant insistence that “Ben is a child” is capable of doing what he couldn’t in fighting back even when the odds seem impossible. Teru is defeated by life, but fighting back in his case might look like something a little less glamorous that starts with eating some humble pie and calling in a favour to get a shot at a regular job he’ll have to take a little more seriously. In one way or another, their accidental road trip clarifies the dynamics of their “brotherly” relationship, but at the same time leads them to a point of division in which moving forward might necessarily mean they’re going in different directions.

Welcome Back screened as part of this year’s Camera Japan.

Trailer (no subtitles)

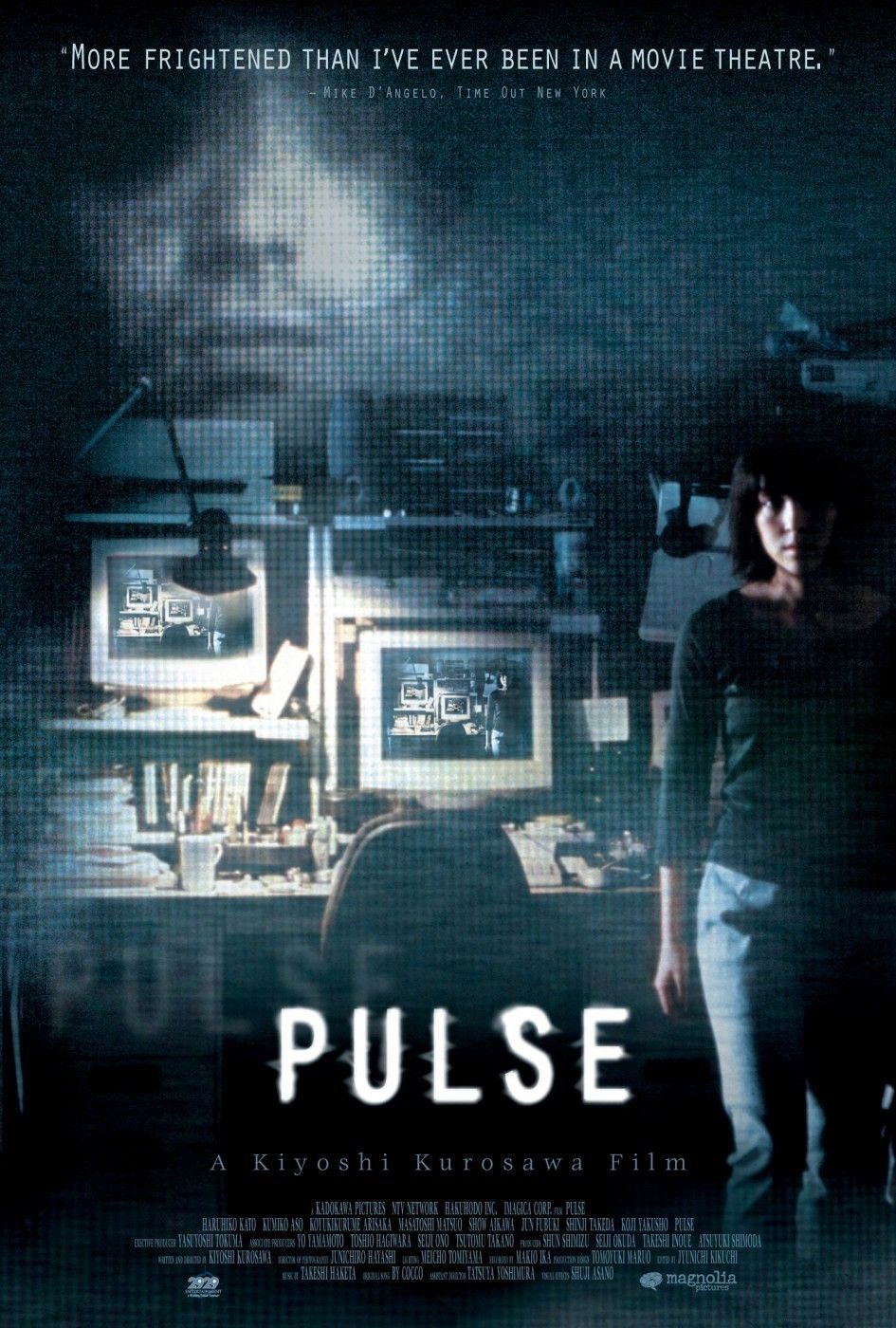

Times change and then they don’t. 2001 was a strange year, once a byword for the future it soon became the past but rather than ushering us into a new era of space exploration and a utopia born of technological advance, it brought us only new anxieties forged by ongoing political instabilities, changes in the world order, and a discomfort in those same advances we were assured would make us free. Japanese cinema, by this time, had become synonymous with horror defined by dripping wet, longhaired ghosts wreaking vengeance against an uncaring world. The genre was almost played out by the time Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s Pulse (回路, Kairo) rolled around, but rather than submitting himself to the inevitability of its demise, Kurosawa took the moribund form and pushed it as far as it could possibility go. Much like the film’s protagonists, Kurosawa determines to go as far as he can in the knowledge that standing still or turning back is consenting to your own obsolescence.

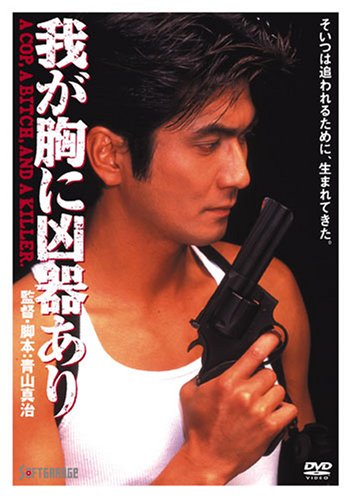

Times change and then they don’t. 2001 was a strange year, once a byword for the future it soon became the past but rather than ushering us into a new era of space exploration and a utopia born of technological advance, it brought us only new anxieties forged by ongoing political instabilities, changes in the world order, and a discomfort in those same advances we were assured would make us free. Japanese cinema, by this time, had become synonymous with horror defined by dripping wet, longhaired ghosts wreaking vengeance against an uncaring world. The genre was almost played out by the time Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s Pulse (回路, Kairo) rolled around, but rather than submitting himself to the inevitability of its demise, Kurosawa took the moribund form and pushed it as far as it could possibility go. Much like the film’s protagonists, Kurosawa determines to go as far as he can in the knowledge that standing still or turning back is consenting to your own obsolescence. Shinji Aoyama would produce one of the most important Japanese films of the early 21st century in Eureka, but like many directors of his generation he came of age during the V-cinema boom. This relatively short lived medium was the new no holds barred arena for fledgling filmmakers who could adhere to a strict budget and shooting schedule but were also aching to spread their wings. After a short period as an AD with fellow V-cinema director now turned international auteur Kiyoshi Kurosawa, Aoyama directed his first straight to video effort – the sex comedy It’s Not in the Textbook!. Released just after his theatrical debut, Helpless, A Weapon in My Heart (我が胸に凶器あり, Waga Mune ni Kyoki Ari, AKA A Cop, A Bitch, and a Killer) is a more typically genre orientated effort with its cops, robbers, and femme fatale setup but like the best examples of the V-cinema trend it bears the signature of its ambitious director making the most of its humble origins.

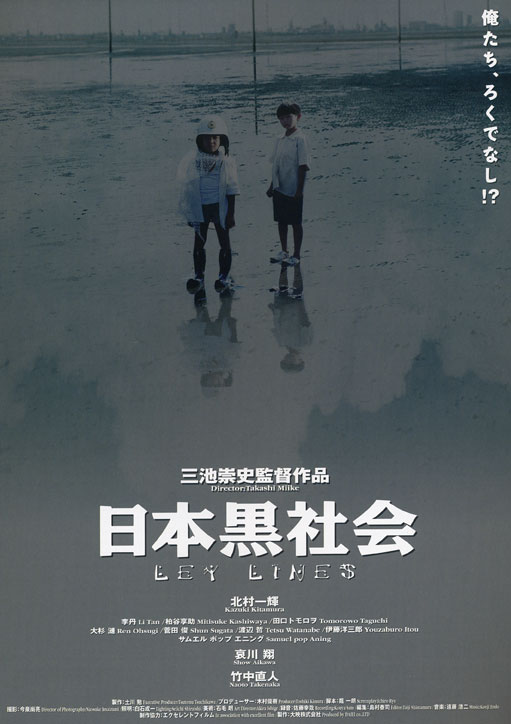

Shinji Aoyama would produce one of the most important Japanese films of the early 21st century in Eureka, but like many directors of his generation he came of age during the V-cinema boom. This relatively short lived medium was the new no holds barred arena for fledgling filmmakers who could adhere to a strict budget and shooting schedule but were also aching to spread their wings. After a short period as an AD with fellow V-cinema director now turned international auteur Kiyoshi Kurosawa, Aoyama directed his first straight to video effort – the sex comedy It’s Not in the Textbook!. Released just after his theatrical debut, Helpless, A Weapon in My Heart (我が胸に凶器あり, Waga Mune ni Kyoki Ari, AKA A Cop, A Bitch, and a Killer) is a more typically genre orientated effort with its cops, robbers, and femme fatale setup but like the best examples of the V-cinema trend it bears the signature of its ambitious director making the most of its humble origins. The three films loosely banded together under the retrospectively applied title of the Black Society Trilogy are not connected in terms of narrative, characters, tone, or location but they do all reflect on attitudes to foreignness, both of a national and of a spiritual kind. Like Tatsuhito in the first film,

The three films loosely banded together under the retrospectively applied title of the Black Society Trilogy are not connected in terms of narrative, characters, tone, or location but they do all reflect on attitudes to foreignness, both of a national and of a spiritual kind. Like Tatsuhito in the first film,