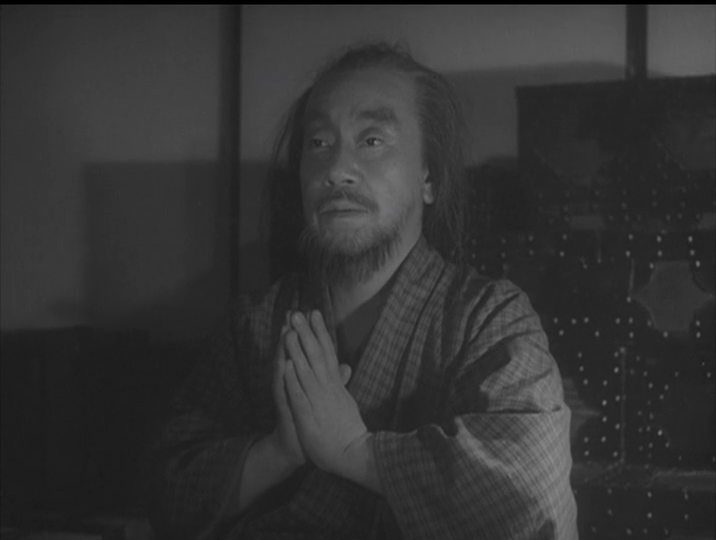

Starring a baby-faced Shintaro Katsu, Tokuzo Tanaka’s adaptation of a popular novel by Toko Kon, Tough Guy (悪名, Akumyo), went on to spawn a 17-film “Akumyo” or “Bad Reputation” series. Asakichi (Shintaro Katsu) is certainly the “tough guy” of the title and fulfilling a certain vision of post-war masculinity in this early Showa tale, yet getting a “bad reputation” is something he ultimately rejects in the film’s closing moments as he continues to straddle a line, not quite the “yakuza” he claims to hate but a noble rogue all the same.

Asakichi is a small-town boy from rural Kawauchi. Despite the nobility which later comes to define his character, he’s disowned by his family after stealing a chicken from a yakuza-affiliated farmer to use in a cock fight. Originally, he skips town, with the farmer’s apparently married sister Kiyo who tells him that she’s pregnant though is probably not telling the truth. In any case, when they get to the next town he discovers she’s been engaging in sex work and breaks up with her, but Kiyo is only one element of his increasingly complicated love life. While staying in the town, Asakichi ends up developing a relationship with besotted former geisha Kotoito (Yaeko Mizutani) whom he eventually agrees to help rescue through another elopement. Meanwhile, he also becomes a “guest” of the local Yoshioka yakuza group and sworn brother of former enemy Sada.(Jiro Tamiya).

The problem is that the Yoshioka gang is small potatoes in the town and does not have the resources to stand up against the hired thugs of the Matsushima red light district who eventually turn up to reclaim Kotoito. While she manages to escape on her own, Asakichi ends up randomly marrying a completely different woman, Okinu (Tamao Nakamura), who cannily makes him sign a contract saying they’re married before she’ll sleep with him. Nevertheless, when he hears that Kotoito came back to look for him and was recaptured, he springs into action and heads to Innoshima to battle agains the Silk Hat Boss and a wily yet fair-minded female yakuza who turns out to be the one really in charge of the island.

Asakichi is, in many ways, an embodiment of a certain kind of masculinity in his determination to do what he sees as right even when others don’t agree with him. Consequently, his moral code seems inconsistent and difficult to define. He was fine with stealing the chicken, but doesn’t like the idea of cheating at gambling (though later does it to get money to rescue Kotoito) despite proving himself an expert at bluff and trickery. Similarly, he hates “yakuza” and refuses to become one, but is willing to stay as their “guest” and to help out when they need extra bodies for a fight. The only thing that certain is that he hates those who abuse their power to oppress the weak, which explains his objection to the yakuza, while otherwise doing what they claim to do but in reality do not in defending the interests of those who cannot defend themselves such as Kotoito who has been sold into the sex trade by a feckless father.

Her position is mirrored in that of the female gang boss, Ito (Chieko Naniwa) , who eventually assumes control over Kotoito’s fate, an ice-cold and fearless leader who nevertheless respects Asakichi’s earnestness and brands him the tough guy of the title after he decides to return alone and accept punishment for freeing Kotoito. In giving them a week’s grace to have a kind of non-honeymoon (on which Okinu actually also comes along), she may not have expected the pair to return and is surprised that Asakichi insists on bringing the matter to a formal close. Eventually he defeats her by refusing to give in, insisting that they see which is stronger, his body or her cane, rather than begging for mercy and thereby accepting her authority. Having defeated her, he breaks the cane in two and throws it in the ocean to stand by his strength alone while crying out that he has won, yet suggesting that he does not want the kind of life that leads to a “bad reputation”. Tanaka makes fantastic use of lighting not least in the final shot of the shining sea that leaves Asakichi alone on the shore, a tiny figure in an expanding landscape.

Trailer (no subtitles)

Kon Ichikawa, wry commenter of his times, turns his ironic eyes to the inherent sexism of the 1960s with a farcical tale of a philandering husband suddenly confronted with the betrayed disappointment of his many mistresses who’ve come together with one aim in mind – his death! Scripted by Natto Wada (Ichikawa’s wife and frequent screenwriter until her retirement in 1965), Ten Dark Women (黒い十人の女, Kuroi Junin no Onna) is an absurd noir-tinged comedy about 10 women who love one man so much that they all want him dead, or at any rate just not alive with one of the others.

Kon Ichikawa, wry commenter of his times, turns his ironic eyes to the inherent sexism of the 1960s with a farcical tale of a philandering husband suddenly confronted with the betrayed disappointment of his many mistresses who’ve come together with one aim in mind – his death! Scripted by Natto Wada (Ichikawa’s wife and frequent screenwriter until her retirement in 1965), Ten Dark Women (黒い十人の女, Kuroi Junin no Onna) is an absurd noir-tinged comedy about 10 women who love one man so much that they all want him dead, or at any rate just not alive with one of the others.