Seijun Suzuki made his first colour film in 1960 – Fighting Delinquents starred young matinee idol Koji Wada as a noble hearted construction worker with a temper who suddenly learns that he is the heir to an aristocratic fortune. Suzuki would make another two youth dramas starring Wada before getting to 1961’s The Wind-of-Youth Group Crosses the Mountain Pass (峠を渡る若い風, Toge wo Wataru Wakai Kaze, AKA Breeze on the Ridge) – this slice of colourful anarchy is a world away from Nikkatsu’s usual action fare though it does make space for the odd pop song or two.

Seijun Suzuki made his first colour film in 1960 – Fighting Delinquents starred young matinee idol Koji Wada as a noble hearted construction worker with a temper who suddenly learns that he is the heir to an aristocratic fortune. Suzuki would make another two youth dramas starring Wada before getting to 1961’s The Wind-of-Youth Group Crosses the Mountain Pass (峠を渡る若い風, Toge wo Wataru Wakai Kaze, AKA Breeze on the Ridge) – this slice of colourful anarchy is a world away from Nikkatsu’s usual action fare though it does make space for the odd pop song or two.

Naive and cheerful university student Shintaro (Koji Wada) loves to travel and has taken off to wander around alone during the summer break. Getting thrown off a regular city bus for not having the cash for a ticket (his request to defer payment is not looked on kindly), Shintaro catches a lift with a group of travelling performers heading into the summer festival in the next town. Once there Shintaro showcases his lack of forethought once again when he happily sets down to start selling some of the “merchandise” he was given as a salary when the last place he worked at went bust. Not having realised that one generally needs a permit to sell goods in a market, Shintaro gets into an argument about the evils of monopolies and freedom verses regulation with the guy on the next stand all of which brings him to the attention of the yakuza. Luckily for Shintaro, he’s run into the nice kind of yakuza who just think he’s funny and invite him to travel on with them for a bit. Being so essentially good hearted and innocent, Shintaro agrees without thinking about all the reasons travelling around with a bunch of shady yakuza might not be a good idea.

Connecting with both the yakuza and the travelling players, Shintaro becomes involved in a number of interconnected crises – the biggest being the fate of the performers when a local gangster type swipes their headline act. The head of the troupe, Kinyo Imai (Shin Morikawa), is a traditional magician who performs in exaggerated Chinese dress complete with Fu Manchu moustache, but it doesn’t really matter how good he is, the rural audience is only here for the strip show. No stripper means no bookings which Kinyo knew already but it’s still a huge blow to his self esteem to realise that his magic doesn’t do the business anymore, especially as he’d always been conflicted about the strippers anyway.

Shintaro is one of Nikkatsu’s wandering heroes but unlike most he’s a cheerful soul who wanders out of a sense of curiosity and adventure rather than a need to escape something or someone at home. He likes meeting new people, even if the relationships are transitory and necessarily shallow, and treats everyone he meets with kindness and an open mind. In return he meets only kind and open people – even the yakuza are a generally decent sort who treat him like a new friend and can be relied upon to come to his aid if called. The only note of sourness arrives in the form of shady gangster Akita (Hiroshi Kondo) who pinches the troupe’s stripper, and their sometime patron who makes an indecent proposal to Kinyo as a kind of bet to decide whether he continues to fund their moribund performing career.

This being a regular program picture there’s not a lot of scope for experimentation but as it’s also a slightly odd entry to the Nikkatsu catalogue Suzuki does have the freedom to spice things up in his own particular way. Making the best use of colour film, Suzuki has a ball capturing Japan’s unique summer festival culture with its giant floats and cheerful market atmosphere. Wandering around the festival in a lengthy POV shot manages to exoticise something which would be quite ordinary to many viewers (at least those not born in large cities) but Suzuki’s other innovations are mostly relegated to one extremely interesting sequence in which Shintaro has a paint fight with yakuza he’s fallen out with (don’t worry, they both end up laughing like school boys). Every time Shintaro gets hit with paint, the entire screen tints to match neatly intensifying the effect and marking an early example of Suzuki’s love of colour play. Warm and goodnatured, The Wind-of-Youth Group Crosses the Mountain Pass is a gentle tale of youth finding its path but also one in which Suzuki takes advantage of the travelling motif to break from the regular programming and present an anarchic carnivale of music and song.

The Wind-of-Youth Group Crosses the Mountain Pass is the second of five films included in Arrow’s Seijun Suzuki: The Early Years. Vol. 1 Seijun Rising: The Youth Movies box set.

Original trailer (English subtitles)

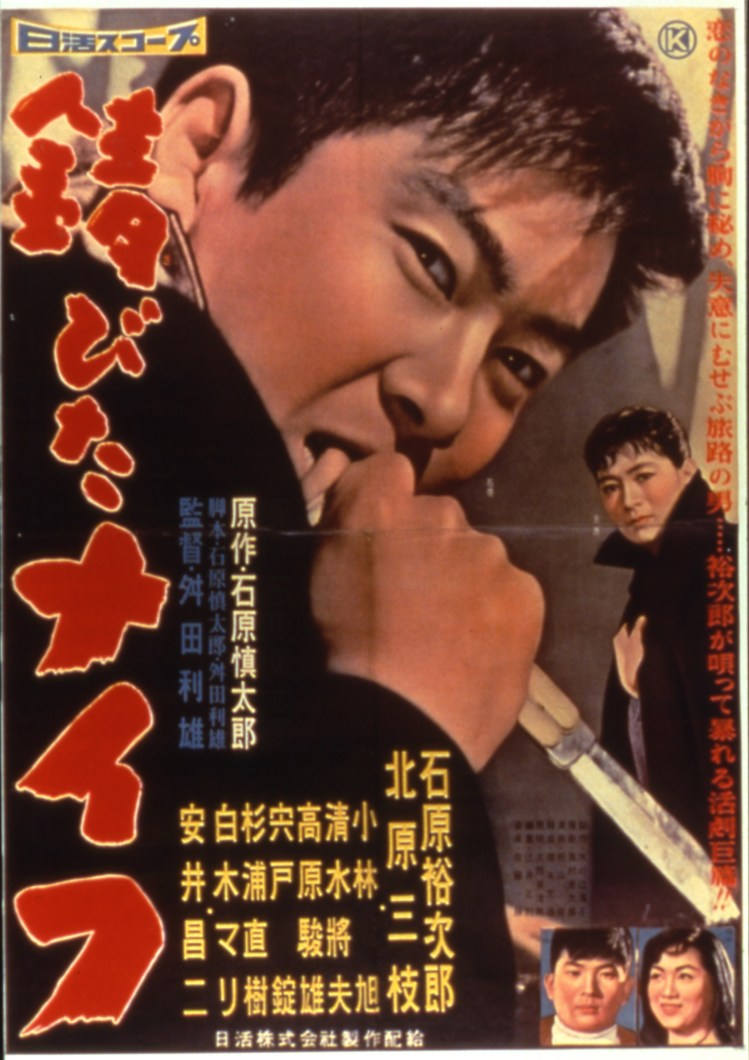

Post-war Japan was in a precarious place but by the mid-1950s, things were beginning to pick up. Unfortunately, this involved picking up a few bad habits too – namely, crime. The yakuza, as far as the movies went, were largely a pre-war affair – noble gangsters who had inherited the codes of samurai honour and were (nominally) committed to protecting the little guy. The first of many collaborations between up and coming director Toshio Masuda and the poster boy for alienated youth, Yujiro Ishihara, Rusty Knife (錆びたナイフ, Sabita Knife) shows us the other kind of movie mobster – the one that would stick for years to come. These petty thugs have no honour and are symptomatic parasites of Japan’s rapidly recovering economy, subverting the desperation of the immediate post-war era and turning it into a nihilistic struggle for total freedom from both laws and morals.

Post-war Japan was in a precarious place but by the mid-1950s, things were beginning to pick up. Unfortunately, this involved picking up a few bad habits too – namely, crime. The yakuza, as far as the movies went, were largely a pre-war affair – noble gangsters who had inherited the codes of samurai honour and were (nominally) committed to protecting the little guy. The first of many collaborations between up and coming director Toshio Masuda and the poster boy for alienated youth, Yujiro Ishihara, Rusty Knife (錆びたナイフ, Sabita Knife) shows us the other kind of movie mobster – the one that would stick for years to come. These petty thugs have no honour and are symptomatic parasites of Japan’s rapidly recovering economy, subverting the desperation of the immediate post-war era and turning it into a nihilistic struggle for total freedom from both laws and morals.

When one thinks of the classic examples of children in Japanese cinema, Hiroshi Shimizu is the name which comes to mind but family chronicler Yasujiro Ozu also made a few notable forays into the genre. I Was Born, But… (大人の見る絵本 生れてはみたけれど, Otona no miru ehon – Umarete wa mita keredo) stars one of the premier child actors of the silent era in Tokkan Kozo (later known as Tomio Aoki) who also worked repeatedly with Shimizu (

When one thinks of the classic examples of children in Japanese cinema, Hiroshi Shimizu is the name which comes to mind but family chronicler Yasujiro Ozu also made a few notable forays into the genre. I Was Born, But… (大人の見る絵本 生れてはみたけれど, Otona no miru ehon – Umarete wa mita keredo) stars one of the premier child actors of the silent era in Tokkan Kozo (later known as Tomio Aoki) who also worked repeatedly with Shimizu ( Despite being at the forefront of early Japanese cinema, directing Japan’s very first talkie, Heinosuke Gosho remains largely unknown overseas. Like many films of the era, much of Gosho’s silent work is lost but the director was among the pioneers of the “shomin-geki” genre which dealt with ordinary, lower middle class society in contemporary Japan. Burden of Life (人生のお荷物, Jinsei no Onimotsu) is another in the long line of girls getting married movies, but Gosho allows his particular brand of irrevent, ironic humour to colour the scene as an ageing patriarch muses on retiring from the fathering business before resentfully remembering his only son, born to him when he was already 50 years old.

Despite being at the forefront of early Japanese cinema, directing Japan’s very first talkie, Heinosuke Gosho remains largely unknown overseas. Like many films of the era, much of Gosho’s silent work is lost but the director was among the pioneers of the “shomin-geki” genre which dealt with ordinary, lower middle class society in contemporary Japan. Burden of Life (人生のお荷物, Jinsei no Onimotsu) is another in the long line of girls getting married movies, but Gosho allows his particular brand of irrevent, ironic humour to colour the scene as an ageing patriarch muses on retiring from the fathering business before resentfully remembering his only son, born to him when he was already 50 years old. It would be a mistake to say that Hiroshi Shimizu made “children’s films” in that his work is not particularly intended for younger audiences though it often takes their point of view. This is certainly true of one of his most well known pieces, Children in the Wind (風の中の子供, Kaze no Naka no Kodomo), which is told entirely from the perspective of the two young boys who suddenly find themselves thrown into an entirely different world when their father is framed for embezzlement and arrested. Encompassing Shimizu’s constant themes of injustice, compassion and resilience, Children in the Wind is one of his kindest films, if perhaps one of his lightest.

It would be a mistake to say that Hiroshi Shimizu made “children’s films” in that his work is not particularly intended for younger audiences though it often takes their point of view. This is certainly true of one of his most well known pieces, Children in the Wind (風の中の子供, Kaze no Naka no Kodomo), which is told entirely from the perspective of the two young boys who suddenly find themselves thrown into an entirely different world when their father is framed for embezzlement and arrested. Encompassing Shimizu’s constant themes of injustice, compassion and resilience, Children in the Wind is one of his kindest films, if perhaps one of his lightest. Japan in 1937 – film is propaganda, yet Hiroshi Shimizu once again does what he needs to do in managing to pay mere lip service to his studio’s aims. Star Athlete (花形選手, Hanagata senshu) is, ostensibly, a college comedy in which a group of university students debate the merits of physical vs cerebral strength and the place of the individual within the group yet it resolutely refuses to give in to the prevailing narrative of the day that those who cannot or will not conform must be left behind.

Japan in 1937 – film is propaganda, yet Hiroshi Shimizu once again does what he needs to do in managing to pay mere lip service to his studio’s aims. Star Athlete (花形選手, Hanagata senshu) is, ostensibly, a college comedy in which a group of university students debate the merits of physical vs cerebral strength and the place of the individual within the group yet it resolutely refuses to give in to the prevailing narrative of the day that those who cannot or will not conform must be left behind.