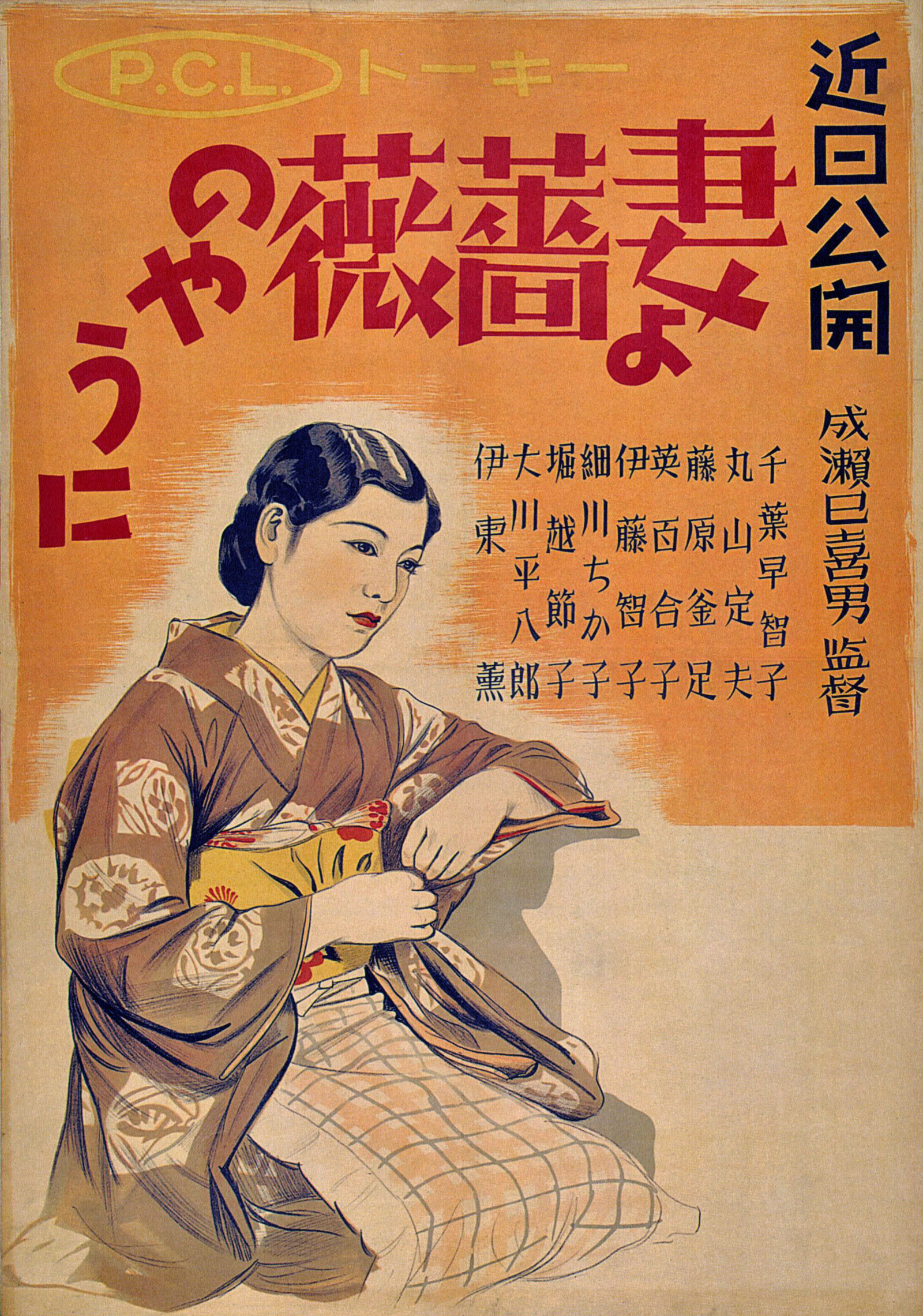

There are two weddings that occur during Yasujiro Shimazu’s Wedding Day (嫁ぐ日まで, Totsugu Hi Made), though we only really see one of them. The earlier part of the film seems to be leading up to the arrival of the widowed father’s second wife as the two daughters find themselves torn in their attachment to their late mother, but as we later discover, this first marriage is only intended to facilitate the second in “freeing” 20-year-old Yoshiko (Setsuko Hara) so that she too may marry.

Then again, perhaps “freeing” is the wrong word, seeing as Yoshiko is given very little choice in anything at all. It’s clear in the opening scenes that Yoshiko has taken over as the lady of the house, looking after the domestic space and raising her younger sister Asako (Yoko Yaguchi) who is still in school. But her mother’s absence is still keenly felt in Yoshiko’s quickening steps to return home after shopping. She’s left the front porch unlocked in anticipation of Asako’s arrival home from school and is anxious that she’ll be put out if she can’t get into the main house, though they could obviously have just given her a key. True to form, Asako has arrived early and come out looking for Yoshiko rather than having to sit and wait. The implication is that there is a domestic need that’s not being met because the house is understaffed and Yoshiko is taking on too much.

This is doubtless why the father, Mr Ubukata (Ko Mihashi), is being pressured into an arranged second marriage, though he doesn’t really seem all that keen and both he and the go-betweens are clear that it’s going to be a “marriage of convenience”. Tsuneko (Sadako Sawamura), a school teacher, seems to be a woman who’s resisted getting married so far and has aged out of the arranged marriage market, which is why she’s only being considered as a second wife to a widower with children. Nevertheless, she’s being taken on mostly to shoulder the domestic burden so that Yoshiko would be free to get married without worrying about leaving her father and sister alone with no one to look after them.

In fact, all of Yoshiko’s actions are dictated by filial piety and duty to the family, which is presumably how the film gets around an increasing desire for more patriotic content in the early 1940s. Asako’s attachment to her late mother is positioned as a barrier to the functioning of this system of social organisation in which feeling is almost secondary. Even if Mr Ubukata insists that it’s important not to forget human feelings and affection while being honest that he wants a wife to do his domestic chores, the point is that the nation is a collection of familial units led by a patriarchal figure to which all must be obedient. Once Yoshiko gets married, she writes to Asako and tells her that she should be nice to their step-mother because she’ll be the one looking after their father in the end once Asako too has married and that’s what will make their father happiest.

As such, Yoshiko’s own wedding arrives almost without warning. She does not marry the young man who’s been interested in her for the entirety of the film, but someone her father chooses, evidently a diplomat, with the help of the same go-betweens who can be seen in the back of the wedding car. The film, in part, seems to be a promotional tool for the song Totsugu Hi Made by Hideko Hirai which plays in a record towards the end where Asako has taken refuge after being scolded by her father by refusing to let go of her late mother’s memory. The lyrics express the mixed feelings of a bride who is giving all her girlish things to a younger sister as she transitions from daughter wife and is breaking from her original family in order to create a new one. Though the film views this as the proper order of things, it is sympathetic to Asako who is being left behind having lost first her mother and then her sister who had become a kind of mother to her.

Everyone has their role to play, and Asako’s is still that of a child as symbolised by her long pigtails. For her part, Tsuneko also does her best to fit into the household and is considerate of both daughters whom she treats kindly and with great sensitivity. Though Yoshiko and Mr Ubukata are keen to erase the memory of the late mother from the house in deference to Tsuneko, when she discovers the photograph Asako had misplaced she gives it back to her and tells her to hang on to it. She also does some of the less pleasant domestic tasks such as scrubbing the floors even if Mr Ubukata tells her to have one of the girls do it instead. But she’s also a part of this system and is fulfilling her role by doing her best to facilitate Yoshiko’s marriage. As she says, a bride should have delicate fingers. A mother, by contrast, those roughed by long years of loving domestic service.

Without her presence, Yoshiko was in danger of ageing before her time. We can see subtle references to the straitened economic circumstances of the wartime era in the talk of the rising costs of vegetables, their late mother’s lessons in thriftiness, and perhaps how the family’s own circumstances have changed as their aunt enquires about their lack of a maid with Yoshiko avowing that they don’t really need one because she can manage on her own. A radio broadcast airs a recruitment ad for welders offering good salaries, hinting perhaps that more hands are needed for the war effort. But in other ways, life continues. Asako’s friends talk about seeing the 1938 French film Prison Without Bars which perhaps reflects Asako’s rebelliousness or the constraining nature of her of her home and life under entrenched patriarchy. Then again, the film very clearly thinks that’s as it should be in encouraging young women to believe that their duty lies in marriage and in obeying husbands and fathers with barely a recognition of their own hopes or desires.