Yasushi Sato, an author closely associated with the port town of Hakodate who took his own life in 1990, has been enjoying something of a cinematic renaissance in the last few years with adaptations of some of his best known works in The Light Shines Only There, Over the Fence, and Sketches of Kaitan City. And Your Bird Can Sing (きみの鳥はうたえる, Kimi no Tori wa Utaeru), taking its title from the classic Beatles song, was his literary debut and won him a nomination for the prestigious Akutagawa Prize in 1981. Unlike the majority of his output, And Your Bird Can Sing was set in pre-bubble Tokyo but perhaps signals something of a recurring theme in its positioning of awkward romance as a potential way out of urban ennui and existential confusion.

Yasushi Sato, an author closely associated with the port town of Hakodate who took his own life in 1990, has been enjoying something of a cinematic renaissance in the last few years with adaptations of some of his best known works in The Light Shines Only There, Over the Fence, and Sketches of Kaitan City. And Your Bird Can Sing (きみの鳥はうたえる, Kimi no Tori wa Utaeru), taking its title from the classic Beatles song, was his literary debut and won him a nomination for the prestigious Akutagawa Prize in 1981. Unlike the majority of his output, And Your Bird Can Sing was set in pre-bubble Tokyo but perhaps signals something of a recurring theme in its positioning of awkward romance as a potential way out of urban ennui and existential confusion.

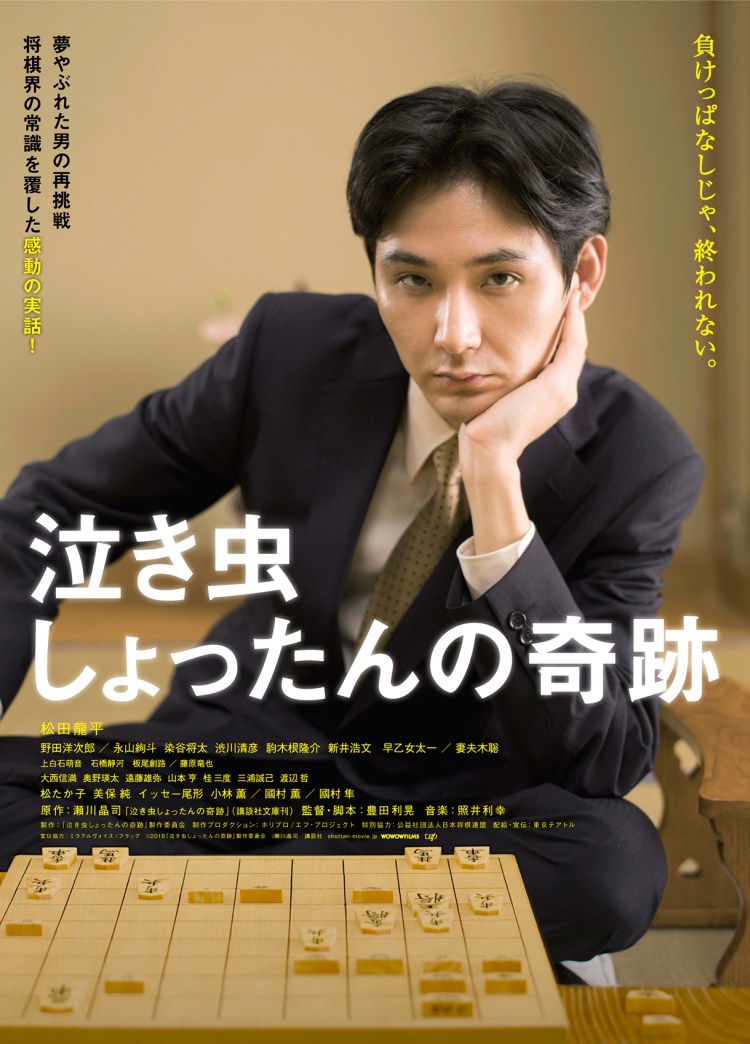

Sho Miyake’s adaptation shifts the action back to Hakodate and the into present day but maintains the awkward triangularity of Sato’s book. The unnamed narrator (Tasuku Emoto), the “Boku” of this “I Novel”, is an apathetic slacker with a part-time job in a book store he can’t really be bothered to go to. After not showing up all day, he wanders past the store at closing time which brings him into contact with co-worker Sachiko (Shizuka Ishibashi) who appears to be leaving with the boss (Masato Hagiwara) but blows him off to come back and flirt with Boku who makes a date with her at a cute bar but falls asleep after getting home and (accidentally) stands her up, drinking all night with his unemployed roommate Shizuo (Shota Sometani) instead. Luckily for Boku, Sachiko forgives him and an awkward romance develops but their relationship becomes still more complicated when Boku introduces Sachiko to Shizuo with whom she proves an instant hit.

This is not, however, the story of an awkward love triangle but the easy fluidity of youth in which unselfishness can prove accidentally destructive. Boku, for all his rejection of conventionality, is more smitten with Sachiko than he’s willing to admit. He counts to 120 waiting for her return, refusing to make a move himself but somehow believing she is choosing him with an odd kind of synchronised telepathy. She pushes forward, he holds back. Boku encourages Shizuo to pursue Sachiko, insisting that she is free to make her choices, and if jealous does his best to hide it. Shizuo, meanwhile, is uncertain. Attracted to Sachiko he sees she prefers Boku but weighs the positivities of being second choice to a man dressing up his fear of intimacy as egalitarianism.

Boku tells us that he wanted the summer to last forever, but in truth his youth is fading. Like Sachiko and Shizuo, he is drifting aimlessly without direction – much to the annoyance of an earnest employee at the store (Tomomitsu Adachi) who prizes rules and order above all else and finds the existence of a man like Boku extremely offensive. Sachiko, meanwhile, has drifted into an affair with her boss who, against the odds, actually seems like a decent guy if one who is perhaps just as lost as our trio and living with no more clarity despite his greater experience. Like Boku, Shizuo too is largely living on alienation as he strenuously resists the fierce love of his admittedly problematic mother (Makiko Watanabe).

“What is love?” one of Sachiko’s seemingly less complicated friends (Ai Yamamoto) asks, “why does everybody lie?”. Everybody is indeed lying, but more to themselves than to others. Fearing rejection they deny their true feelings and bury themselves in temporary, hedonistic pleasures. Boku reveals that he hoped Sachiko and Shizuo would fall in love so that he would get to know a different side to Sachiko through his friend, as if he could hover around them like transparent air. The problem is Boku doesn’t quite want to exist, and what is loving and being loved other than a proof of existence? Sachiko prompts, and she waits, and then she wonders if she should take Boku at his word and settle for Shizuo only for Boku to reach his sudden moment of clarity at summer’s end. A melancholy exploration of youthful ennui and existential anxiety, And Your Bird Can Sing is a beautifully pitched evocation of the eternal summer and the awkward, tentative bonds which finally give it meaning.

And Your Bird Can Sing was screened as part of the 2019 Nippon Connection Film Festival.

Original trailer (English subtitles)