When examining the influences of classic European cinema on Japanese filmmaking, you rarely end up with Fellini. Nevertheless, Fellini looms large over the indie comedy Choklietta (チョコリエッタ) and the director, Shiori Kazama, even leaves a post-credits dedication to Italy’s master of the surreal as a thank you for inspiring the fifteen year old her to make movies. Full of knowing nods to the world of classic cinema, Chokolietta is a charming, if over long, coming of age drama which becomes a meditation on both personal and national notions of loss.

When examining the influences of classic European cinema on Japanese filmmaking, you rarely end up with Fellini. Nevertheless, Fellini looms large over the indie comedy Choklietta (チョコリエッタ) and the director, Shiori Kazama, even leaves a post-credits dedication to Italy’s master of the surreal as a thank you for inspiring the fifteen year old her to make movies. Full of knowing nods to the world of classic cinema, Chokolietta is a charming, if over long, coming of age drama which becomes a meditation on both personal and national notions of loss.

The story begins in the summer of 2010 when five year old Chiyoko (Aoi Morikawa) is involved in a car accident that results in the death of her mother. Flash forward ten years and Chiyoko is a slightly strange high school girl and a member of the film club. Her parents, as far as she knows, were both big fans of Federico Fellini – in fact the family dog is named “Giulietta” after Fellini’s muse and later wife Giuletta Masina. As a child, Chiyoko also received the strange nickname of “Chokolietta” from her mother which also seems to be inspired by the star. Sadly, their Giulietta has also recently passed away removing Chiyoko’s final link to her late mother and once again forcing her to address the lingering feelings of grief and confusion which have continued to plague her all these years.

At this point Chiyoko goes looking for the DVD of La Strada they watched in film club last year which leads her to the now graduated Masamura Masaoka (Masaki Suda). Masaoka is an equally strange boy with possible sociopathic tendencies though he does own a large collection of classic DVDs and the pair settle down to return to the world of Fellini. Eventually Masaoka convinces “Chokolietta” to star in a movie for him and the two take off on a crazy road trip recreating La Strada where Masaoka stands in for the strong man Zampanò and Chiyoko plays the fragile Gelsomina.

Thankfully, the partnership between Chiyoko and Masaoka is not quite as doom laden and filled with cruelty as that between Gelsomina and Zampanò. Though Masaoka often talks of the desire to kill and Chiyoko the desire to die, both appear superficial and are never presented as actual choices either will seriously act on. Masaoka is cast in the role of the strong man but he more closely resembles The Fool as he gently guides Chiyoko onto a path of self realisation that will help her finally learn to reach a tentative acceptance with the past and begin to move forward rather than futilely trying to remain static. Of course, he’s also forcing himself into a realisation that he doesn’t have to play the role he’s been cast in either and so it doesn’t follow that one has to behave in the way people have come to expect simply because they expect it.

Technically speaking the bulk of the story takes place in a putative future – around 2020, or ten years or so after the death of Chiyoko’s mother in 2010. 2010 is also a significant date as it’s the summer before the earthquake and tsunami struck the Japan the following March causing much devastation and loss of life as well as the resultant nuclear meltdown which has continued to become a cultural as well as physical scar. The journey the pair make takes them on a fairly desolate route past no entry signs into ghostly abandoned shopping arcades still strewn with the remnants of a former, bustling city life but now peopled only by a trio of silent, stick bearing men. This is a land of ghosts, both literal and figural but like most things, the only way out is through.

Taking a cue from Fellini, Chiyoko has frequent visions of her her deceased mother and fantastical sequences such as boarding a whale bus like the whale in Casanova or suddenly seeing Gelsomina and an entourage of dwarfs trailing past her. Her world is a fantastical one in which her daydreams have equal, or perhaps greater, weight to the reality. Her now empty indoor dog house comes to take on a symbolic dimension that represents an entirety of her past her life as if she herself, or the dog she claimed to want to become, had been hiding inside it all along. The film returns to La Strada in its final sequence only to subvert that film’s famous ending as where Zampanò’s animalistic, foetal howling spoke of an ultimate desolation and the discovery of a truth it may be better not to acknowledge, here there is a least hope for a brighter future with the past remaining where it belongs.

However, Chokolietta runs to a mammoth 159 minutes and proves far too meandering to justify its lengthy running time. Truth be told, the pace is refreshingly brisk yet the central road trip doesn’t start until 90 minutes in and there are another 30 minutes after it ends. It’s cutesy and fun but runs out of steam long before the credits roll and ultimately lacks the necessary focus to make the desired impact. That said there are some pretty nice moments and a cineliterate tone that remains endearing rather than irritating all of which add up to make Chokolietta an uneven, if broadly enjoyable, experience though one which never quite reaches its potential.

Unsubtitled trailer:

Bonus – here’s an unsubtitled trailer for La Strada (which is possibly the most heartbreaking film ever made).

Also the other two Fellini movies mentioned in the film:

Casanova

and Amacord (original US release trailer)

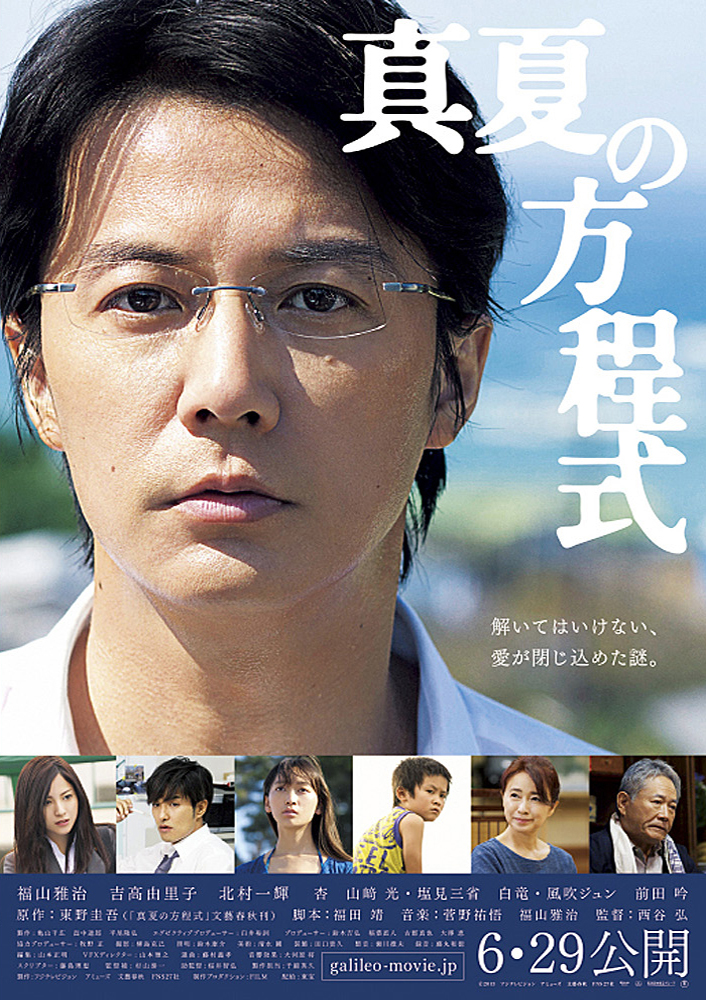

Sometimes it’s handy to know an omniscient genius detective, but then again sometimes it’s not. You have to wonder why people keep inviting famous detectives to their parties given what’s obviously going to unfold – they do rather seem to be a magnet for murders. Anyhow, the famous physicist and sometime consultant to Japan’s police force, “Galileo”, is about to have another busman’s holiday as he travels to a small coastal town which is currently holding a mediation between an offshore mining company and the local residents who are worried about the development’s effects on the area’s sea life.

Sometimes it’s handy to know an omniscient genius detective, but then again sometimes it’s not. You have to wonder why people keep inviting famous detectives to their parties given what’s obviously going to unfold – they do rather seem to be a magnet for murders. Anyhow, the famous physicist and sometime consultant to Japan’s police force, “Galileo”, is about to have another busman’s holiday as he travels to a small coastal town which is currently holding a mediation between an offshore mining company and the local residents who are worried about the development’s effects on the area’s sea life. As you read the words “adapted from the novel by Kanae Minato” you know that however cute and cuddly the blurb on the back may make it sound, there will be pain and suffering at its foundation. So it is with A Chorus of Angels (北のカナリアたち, Kita no Kanariatachi) which sells itself as a kind of mini-take on Twenty-Four Eyes (“Twelve Eyes” – if you will) as a middle aged former school mistress meets up with her six former charges only to discover that her own actions have cast an irrevocable shadow over the very sunlight she was determined to shine on their otherwise troubled young lives.

As you read the words “adapted from the novel by Kanae Minato” you know that however cute and cuddly the blurb on the back may make it sound, there will be pain and suffering at its foundation. So it is with A Chorus of Angels (北のカナリアたち, Kita no Kanariatachi) which sells itself as a kind of mini-take on Twenty-Four Eyes (“Twelve Eyes” – if you will) as a middle aged former school mistress meets up with her six former charges only to discover that her own actions have cast an irrevocable shadow over the very sunlight she was determined to shine on their otherwise troubled young lives. Despite being one of the most prolific directors of the ‘80s and ‘90s, the work of Yoshimitsu Morita has not often travelled extensively overseas. Though frequently appearing at high profile international film festivals, few of Morita’s films have been released outside of Japan and largely he’s still best remembered for his hugely influential (and oft re-visited) 1983 black comedy, The Family Game. In part, this has to be down to Morita’s own zigzagging career which saw him mixing arthouse aesthetics with more populist projects. Main Theme is definitely in the latter category and is one of the many commercial teen idol vehicles he tackled in the 1980s.

Despite being one of the most prolific directors of the ‘80s and ‘90s, the work of Yoshimitsu Morita has not often travelled extensively overseas. Though frequently appearing at high profile international film festivals, few of Morita’s films have been released outside of Japan and largely he’s still best remembered for his hugely influential (and oft re-visited) 1983 black comedy, The Family Game. In part, this has to be down to Morita’s own zigzagging career which saw him mixing arthouse aesthetics with more populist projects. Main Theme is definitely in the latter category and is one of the many commercial teen idol vehicles he tackled in the 1980s. Aside from the original 1960 version of The Housemaid (and this perhaps only because of its modern “remake”), mid 20th century Korean Cinema has been severely neglected overseas. Ha Kil-jong’s The March of Fools (바보들의 행진, Babodeul-ui haengjin) is almost unknown abroad but consistently tops Korean lists of the country’s best cinema and has been both enormously influential on later filmmakers and fondly remembered by audiences.

Aside from the original 1960 version of The Housemaid (and this perhaps only because of its modern “remake”), mid 20th century Korean Cinema has been severely neglected overseas. Ha Kil-jong’s The March of Fools (바보들의 행진, Babodeul-ui haengjin) is almost unknown abroad but consistently tops Korean lists of the country’s best cinema and has been both enormously influential on later filmmakers and fondly remembered by audiences. The work of director Yuki Tanada has had a predominant focus on the stories of independent young women but The Cowards Who Looked to the Sky sees her shift focus slightly as the troubled relationship between a middle aged housewife who escapes her humdrum life through cosplay and an ordinary high school boy takes centre stage. Based on the novel of the same name by Misumi Kubo, The Cowards Who Looked to the Sky (ふがいない僕は空を見た, Fugainai Boku wa Sora wo Mita) also tackles the difficult themes of social stigma, the power of rumour, teenage poverty, elder care, childbirth and even pedophilia which is, to be frank, a little too much to be going on with.

The work of director Yuki Tanada has had a predominant focus on the stories of independent young women but The Cowards Who Looked to the Sky sees her shift focus slightly as the troubled relationship between a middle aged housewife who escapes her humdrum life through cosplay and an ordinary high school boy takes centre stage. Based on the novel of the same name by Misumi Kubo, The Cowards Who Looked to the Sky (ふがいない僕は空を見た, Fugainai Boku wa Sora wo Mita) also tackles the difficult themes of social stigma, the power of rumour, teenage poverty, elder care, childbirth and even pedophilia which is, to be frank, a little too much to be going on with. “Being good”. What does that mean? Is it as simple as “not being bad” (whatever that means) or perhaps it’s just abiding by the moral conventions of your society though those may be, no – are, questionable ideas in themselves. Mipo O follows up her hard hitting modern romance The Light Shines Only There by attempting to answer this question through looking at the stories of three ordinary people whose lives are touched by human cruelty.

“Being good”. What does that mean? Is it as simple as “not being bad” (whatever that means) or perhaps it’s just abiding by the moral conventions of your society though those may be, no – are, questionable ideas in themselves. Mipo O follows up her hard hitting modern romance The Light Shines Only There by attempting to answer this question through looking at the stories of three ordinary people whose lives are touched by human cruelty. When it comes to cinematic adaptations of popular novelists, Keigo Higashino seems to have received more attention than most. Perhaps this is because he works in so many different genres from detective fiction (including his all powerful Galileo franchise) to family melodrama but it has to be said that his work manages to home in on the kind of films which have the potential to become a box office smash. The Letter (手紙, Tegami) finds him in the familiar territory of sentimental drama as its put upon protagonist battles unfairness and discrimination based on a set of rigid social codes.

When it comes to cinematic adaptations of popular novelists, Keigo Higashino seems to have received more attention than most. Perhaps this is because he works in so many different genres from detective fiction (including his all powerful Galileo franchise) to family melodrama but it has to be said that his work manages to home in on the kind of films which have the potential to become a box office smash. The Letter (手紙, Tegami) finds him in the familiar territory of sentimental drama as its put upon protagonist battles unfairness and discrimination based on a set of rigid social codes. Kihachi Okamoto might be most often remembered for his samurai pictures including the landmark Sword of Doom but he had a long and extremely varied career which saw him tackle just about every conceivable genre and each from his own characteristically off-centre vantage point. The Elegant Life of Mr. Everyman (江分利満氏の優雅な生活, Eburi Man-shi no Yugana Seikatsu) sees him step into the world of the salaryman comedy as his hapless office worker reaches a dull middle age filled with drinking and regret imbued with good humour.

Kihachi Okamoto might be most often remembered for his samurai pictures including the landmark Sword of Doom but he had a long and extremely varied career which saw him tackle just about every conceivable genre and each from his own characteristically off-centre vantage point. The Elegant Life of Mr. Everyman (江分利満氏の優雅な生活, Eburi Man-shi no Yugana Seikatsu) sees him step into the world of the salaryman comedy as his hapless office worker reaches a dull middle age filled with drinking and regret imbued with good humour. How exactly do you lose a war? It’s not as if you can simply telephone your opponents and say “so sorry, I’m a little busy today so perhaps we could agree not to kill each other for bit? Talk later, tata.” The Emperor in August examines the last few days in the summer of 1945 as Japan attempts to convince itself to end the conflict. Previously recounted by Kihachi Okamoto in 1967 under the title Japan’s Longest Day, The Emperor in August (日本のいちばん長い日, Nihon no Ichiban Nagai Hi) proves that stately events are not always as gracefully carried off as they may appear on the surface.

How exactly do you lose a war? It’s not as if you can simply telephone your opponents and say “so sorry, I’m a little busy today so perhaps we could agree not to kill each other for bit? Talk later, tata.” The Emperor in August examines the last few days in the summer of 1945 as Japan attempts to convince itself to end the conflict. Previously recounted by Kihachi Okamoto in 1967 under the title Japan’s Longest Day, The Emperor in August (日本のいちばん長い日, Nihon no Ichiban Nagai Hi) proves that stately events are not always as gracefully carried off as they may appear on the surface.