By 1962 the Japanese economy had begun to improve and with the Olympics on the horizon the nation was beginning to look forward towards hoped for prosperity rather than back towards the intense suffering that had defined the post-war era. There would be, however, a kind of reckoning to be had if not quite yet. Yuzo Kawashima’s Elegant Beast (しとやかな獣, Shitoyakana Kemono) is perhaps among the first to start asking questions about what the legacy of the immediate aftermath of the war might be. It may have been impossible to survive with one’s integrity entirely intact, but how should one proceed now that there is less need to be so self serving, calculating, and cruel when there is more food on the table?

By 1962 the Japanese economy had begun to improve and with the Olympics on the horizon the nation was beginning to look forward towards hoped for prosperity rather than back towards the intense suffering that had defined the post-war era. There would be, however, a kind of reckoning to be had if not quite yet. Yuzo Kawashima’s Elegant Beast (しとやかな獣, Shitoyakana Kemono) is perhaps among the first to start asking questions about what the legacy of the immediate aftermath of the war might be. It may have been impossible to survive with one’s integrity entirely intact, but how should one proceed now that there is less need to be so self serving, calculating, and cruel when there is more food on the table?

The Maedas may not be the best people to ask. Carrying the scars of their poverty, they have made a “comfortable” life for themselves in a cramped flat on the fifth floor of an ordinary walk-up apartment building. When we first meet them, dad Tokizo (Yunosuke Ito) and mum Yoshino (Hisano Yamaoka) are having a furious tidying up because they’ll shortly be receiving visitors, only unlike most they’re quickly trying to scuzz up the apartment so that they look sufficiently humble. When their guests arrive, it turns out to be the boss of their only son Minoru (Manamitsu Kawabata) who has come along with one of the artists he represents and his accountant, to have a word about possible embezzlement. Tokizo and Yoshino outdo themselves with humility, pointing out the simplicity of their surroundings, and appear offended that their son is being accused of thievery but of course in reality they know all about it and are willing accomplices in his scheming. Tokizo hasn’t had a steady job since coming back from the war and the entire family is supported by the kids with the remainder of their income coming from daughter Tomoko (Yuko Hamada) who has become the mistress of a famous author (Kyu Sazanka).

Universally unrepentant, cracks start to appear in the Maedas’ morally dubious existence when they begin to realise that Minoru is not quite on the level. He’s only been giving them a portion of the money he’s been stealing – something they can understand and perhaps even admire, if it were not that he’s given most of it to a lover to fund her hotel business. The surprise twist is that the lover is none other than the accountant at the company Minoru had been working for, Yukie (Ayako Wakao), who is a widow with a 5-year-old son (which is to say, not Minoru’s usual type). Now that the hotel is fully funded and the scam has been exposed, Yukie feels there’s no more need to associate herself with lowly punks like Minoru and draws the affair to a businesslike conclusion.

Yukie is, perhaps, the “elegant beast” of the title. Refined, seemingly sweet and innocent, she inspires trust and affection. The slightest suspicions are unlikely to fall on her – something she well knows and is prepared to use to her advantage, along with her sex appeal and, ironically, reduced desirability in the marriage stakes as a widow with a child. Yukie has her dreams and they are ordinary enough. She wants a peaceful, stable life in economic comfort alone with her son. She does not want to remarry and means to be independent which necessarily means industrious. Thus she needs to get her hotel business off the ground as quickly as possible. She needed money, a lot of money, much more than she could get “honestly” but she didn’t want to dirty herself with crime and so she used the tools at her disposal, making her “weakness” a strength as she later puts it. Using her womanliness as a weapon against venal men, she convinced them to ruin themselves on her behalf and thereafter resolved to put the past behind her.

The past is, however, difficult to forget. “Your mind still wears an old fashioned coat”, the quip happy Minoru tells his father as he laments the new society’s tolerance for youthful ebullience and reluctance to forgive the wartime generation for even its most recent transgressions. As much as they resent her, there is perhaps a grudging admiration for a woman like Yukie who has managed to outsmart them all while, technically at least, remaining on the right side of the law. Tomoko, on the other hand, seems to be losing out in playing much the same game by the old rules. Essentially pimped out by her dad, she’s damned herself by becoming the mistress of one man who is becoming rather bored of her family’s obvious attempts to bleed him dry, rather than fleecing several at the same time and bending them to her will as Yukie has managed to do. Old fashioned thinking won’t get you far in this world. The Maedas, however, seem to be out of ideas.

In the closing moments, they may ponder abandoning their hard-won apartment, believing that there’s always trouble brewing in the big city and the clean country air may be what they really need to thrive but, it’s clear that this insular claustrophobic environment filled with peep holes and tiny imprisoning windows will be near impossible to escape. Tokizo hasn’t left the apartment for the entire picture. A woman ascends the stairs, walking purposefully towards a future of her own making, while the Maedas remain locked inside unable to escape the painful legacy of post-war poverty for the bright, if no more ethical, lights of a consumerist future dancing quietly on the horizon.

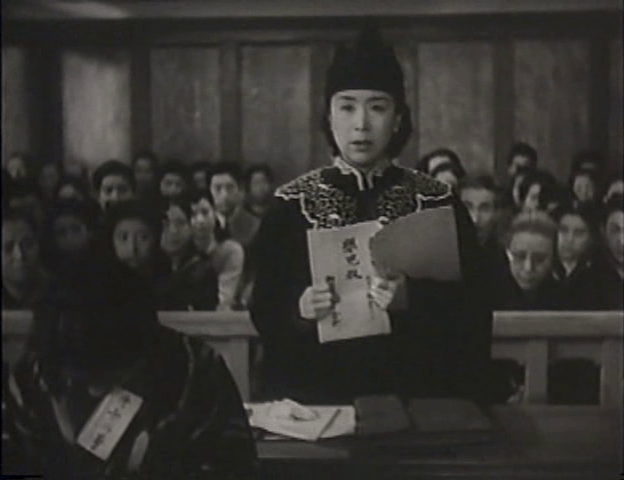

Female suffering in an oppressive society had always been at the forefront of Mizoguchi’s filmmaking even if he, like many of his contemporaries, found his aims frustrated by the increasingly censorious militarist regime. In some senses, the early days of occupation may not have been much better as one form of propaganda was essentially substituted for another if one that most would find more palatable. The first of his “women’s liberation trilogy”, Victory of Women (女性の勝利,

Female suffering in an oppressive society had always been at the forefront of Mizoguchi’s filmmaking even if he, like many of his contemporaries, found his aims frustrated by the increasingly censorious militarist regime. In some senses, the early days of occupation may not have been much better as one form of propaganda was essentially substituted for another if one that most would find more palatable. The first of his “women’s liberation trilogy”, Victory of Women (女性の勝利,

Kon Ichikawa was born in 1915, just four years later than the subject of his 1989 film Actress (映画女優, Eiga Joyu) which uses the pre-directorial career of one of Japanese cinema’s most respected actresses, Kinuyo Tanaka, to explore the development of Japanese cinema itself. Tanaka was born in poverty in 1909 and worked as a jobbing film actress before being “discovered” by Hiroshi Shimizu and becoming one of Shochiku’s most bankable stars. The script is co-written by Kaneto Shindo who was fairly close to the action as an assistant under Kenji Mizoguchi at Shochiku in the ‘40s before being drafted into the war. A commemorative exercise marking the tenth anniversary of Tanaka’s death from a brain tumour in 1977, Ichikawa’s film never quite escapes from the biopic straightjacket and only gives a superficial picture of its star but seems content to revel in the nostalgia of a, by then, forgotten golden age.

Kon Ichikawa was born in 1915, just four years later than the subject of his 1989 film Actress (映画女優, Eiga Joyu) which uses the pre-directorial career of one of Japanese cinema’s most respected actresses, Kinuyo Tanaka, to explore the development of Japanese cinema itself. Tanaka was born in poverty in 1909 and worked as a jobbing film actress before being “discovered” by Hiroshi Shimizu and becoming one of Shochiku’s most bankable stars. The script is co-written by Kaneto Shindo who was fairly close to the action as an assistant under Kenji Mizoguchi at Shochiku in the ‘40s before being drafted into the war. A commemorative exercise marking the tenth anniversary of Tanaka’s death from a brain tumour in 1977, Ichikawa’s film never quite escapes from the biopic straightjacket and only gives a superficial picture of its star but seems content to revel in the nostalgia of a, by then, forgotten golden age. Feelings can creep up just like that, to quote another movie. Like Wong Kar-Wai’s In the Mood for Love, Temptation (誘惑, Yuwaku) also echoes Lean’s Brief Encounter with its strains of accidental romance between unavailable people even if only one of the pair is already married. However, this time there’s much less deliberate moralising though the environment itself is a fertile breeding ground for the judgemental.

Feelings can creep up just like that, to quote another movie. Like Wong Kar-Wai’s In the Mood for Love, Temptation (誘惑, Yuwaku) also echoes Lean’s Brief Encounter with its strains of accidental romance between unavailable people even if only one of the pair is already married. However, this time there’s much less deliberate moralising though the environment itself is a fertile breeding ground for the judgemental.

Female sexuality often takes centre stage in the work of Kaneto Shindo but in the Iron Crown (鉄輪, Kanawa) it does so quite literally as he refracts a modern tale of marital infidelity through the mirror of ancient Noh theatre. Taking his queue from the Noh play of the same name, Shindo intercuts the story of a contemporary middle aged woman who finds herself betrayed and then abandoned by her selfish husband with the supernaturally tinged tale of a woman going mad in the Heian era.

Female sexuality often takes centre stage in the work of Kaneto Shindo but in the Iron Crown (鉄輪, Kanawa) it does so quite literally as he refracts a modern tale of marital infidelity through the mirror of ancient Noh theatre. Taking his queue from the Noh play of the same name, Shindo intercuts the story of a contemporary middle aged woman who finds herself betrayed and then abandoned by her selfish husband with the supernaturally tinged tale of a woman going mad in the Heian era.