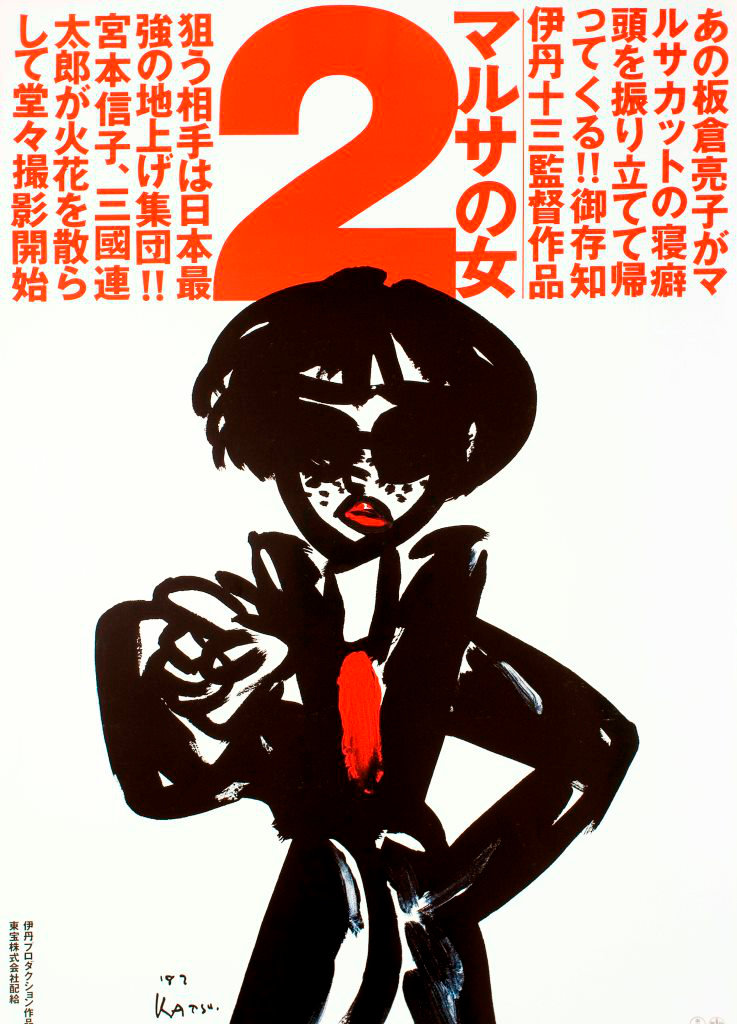

“Yakuza are vain, treat them politely,” the heroine of Juzo Itami’s 1992 comedy Minbo, or The Gentle Art of Japanese Extortion (ミンボーの女, Minbo no Onna) instructs a hapless pair of hotel employees trying to solve the organised crime problem at their hotel, but it’s a lesson Itami would go on to learn himself after he was attacked by gangsters who slashed his face and neck with knives. Itami in fact died in fairly suspicious circumstances in 1997 having fallen from the roof of a high-rise building leaving a note behind him explaining his “suicide” was intended to prove his innocence in regards to an upcoming newspaper story alleging an affair with a young actress. Given Itami’s films had often made a point of skewering Japanese traditions and that taking one’s own life is not the way most would choose to clear their name, it has long been suggested that his death was staged by yakuza who’d continued to harass him ever since the film’s release.

It’s true enough that Minbo may have touched a nerve in undercutting the yakuza’s preferred image of themselves as the inheritors of samurai valour standing up for the oppressed masses against a cruel authority. Of course, that isn’t really how it works and getting the yakuza on your side in a civil dispute may be a case of out of the frying pan into the fire. It’s the yakuza themselves who are the oppressive authority ruling by fear and intimidation. Even so, the yakuza as an institution were in a moment of flux in the early ‘90s following the collapse of the bubble economy during which they’d shifted further away from the street thuggery of the post-war era into a newly corporatised if no more respectable occupation. This change is perhaps exemplified by “minbo”, a kind of fraud in which gangsters get involved in civil disputes underpinned with the thinly veiled threat of violence.

The yakuza who plague the Hotel Europa, for example, pull petty tricks such as “discovering” a cooked cockroach in the middle of a lasagne, or claiming to have left a bag of cash behind which is later handed back to the “wrong” person by the front desk who probably should have asked for ID. Itami frames the presence of the yakuza as a kind of infestation, suggesting that if you do not tackle it right away it soon takes over and cannot be removed. Dealing with the problem directly may cause it to get worse in the short term, but only by doing so can you ever be rid of them once and for all. At least that’s the advice given by forthright attorney Mahiru (Nobuko Miyamoto) who demonstrated that the only way to deal with yakuza is to show them that you aren’t afraid because at the end of the day the law is on your side.

Part of the “woman” cycle in which Itami’s wife Nobuko Miyamoto stars as a sometimes eccentric yet infinitely capable woman solving the problems of contemporary Japan through old-fashioned earnestness and everyday decency, Minbo finds its fearless heroine explaining that the yakuza themselves are a kind of con. In general they won’t hurt civilians because then they’re much more likely to be arrested. Going to prison is incredibly expensive and therefore not likely to prove cost effective. She knows that if she can catch them admitting they’ve committed a “crime” then they can’t touch her, and they won’t. They do however go after the rather more naive hotel boss Kobayashi (Akira Takarada) whom they try to frame for the rape of a bar hostess, drugging him after he unwisely agreed to meet them alone to hand over blackmail money. Then again, the hotel isn’t entirely whiter than white either. Kobayashi admits they can’t pull strings with the health ministry over the cockroach incident because they previously used them to cover up a previous instance of food poisoning.

In any case, the yakuza end up looking very grubby indeed. It’s hard to call yourself a defender of the oppressed when you’re pulling petty stunts no better than a backstreet chancer. Yet like any kind of irritating insect, they too begin to evolve gradually developing a kind of immunity to Mahiru’s tactics in themselves manipulating law only they aren’t as good as she is and they are after all in the wrong. She’s a little a wrong too in that if pushed too far the yakuza will indeed stoop to physical violence against civilians, but she also knows that they thrive on fear and that to beat them she may have to put her safety on the line to prove they have no power over her. It seems Itami felt something similar issuing a statement shortly after his attack to the effect that “Yakuza must not be allowed to deprive us of our freedom through violence and intimidation, and this is the message of my movie”. As gently humorous as any of Itami’s movies and no less earnest, Minbo paints the yakuza as a plague on post-bubble Japan and suggests that it’s about time they were shown the door.

Trailer (no subtitles)

Kenji Miyazawa is one of the giants of modern Japanese literature. Studied in schools and beloved by children everywhere, Night on the Galactic Railroad has become a cultural touchstone but Miyazawa died from pneumonia at 37 years of age long before his work was widely appreciated. Night Train to the Stars (わが心の銀河鉄道 宮沢賢治物語, Waga Kokoro no Ginga Tetsudo: Miyazawa Kenji no Monogatari), commissioned to mark the centenary of Miyazawa’s birth, attempts to tell his story, set as it is against the backdrop of rising militarism.

Kenji Miyazawa is one of the giants of modern Japanese literature. Studied in schools and beloved by children everywhere, Night on the Galactic Railroad has become a cultural touchstone but Miyazawa died from pneumonia at 37 years of age long before his work was widely appreciated. Night Train to the Stars (わが心の銀河鉄道 宮沢賢治物語, Waga Kokoro no Ginga Tetsudo: Miyazawa Kenji no Monogatari), commissioned to mark the centenary of Miyazawa’s birth, attempts to tell his story, set as it is against the backdrop of rising militarism.