Having made a name for herself at Nikkatsu, Meiko Kaji was one of many who declined to continue working with the studio after it shifted production entirely to its Roman Porno line of softcore erotic cinema. Her exit, however, proved fortuitous for rival studio Toei who were urgently looking for a new female star following the sudden retirement of Junko Fuji who gave up acting after marrying a kabuki actor (she’d return a few years later working in television and subsequently films under the name Sumiko Fuji). With her feisty intensity and zeitgeisty energy Kaji would seem to be exactly what Toei were looking for. Her first vehicle for the studio, Wandering Ginza Butterfly (銀蝶渡り鳥, Gincho Wataridori) finds her attempting to forge a new star identity stepping into the space vacated by Fuji and making it her own in the midst of Toei’s ninkyo eiga decline.

Set in the contemporary era, the film opens with a brief prologue at a woman’s prison in which new girl Tome (Kayako Sono) attempts to claim a space for herself by immediately challenging the boss of her new cell only for Nami (Meiko Kaji) to calmly defuse the situation with a traditional gambler’s introduction very much in keeping with Toei’s gambling films many of which had starred Fuji such as the Red Peony Gambler series which is perhaps referenced in Nami’s nickname of the Red Cherry Blossom. The action then shifts to a year later with Nami returning to Ginza in the hope of locating a woman, Saeko (Mieko Aoyagi), to thank her for writing a petition to get her prison sentence for killing a yakuza boss who had killed two members of her all-female biker gang reduced. On the train, however, she’s accosted by a mysterious man who rudely kisses her in order to hide from gangsters chasing him and is thereafter dragged into local intrigue after realising that a shady new yakuza group, Owada Enterprises, is at the centre of the injustice affecting all her friends new and old.

As one of her new friends puts it, every girl in Ginza has a wound from the past she’d rather not talk about yet Nami’s particular sense of shame regarding her misspent biker girl youth and desire to atone are singular markers of her ninkyo inspired path to heroism. She’s just come out of prison, and now she’s going to clean up Ginza getting rid of rubbish, post-war yakuza who ignore the code and exploit “honest” people through underhanded methods such as buying up their debts to force them out of business. Discovering that Saeko has lost her business to Owada and thereafter became a regular bar girl but is now suffering with a serious illness and unable to work, Nami takes her spot at Bar Broncho while funnelling money to her through a mutual friend worried she wouldn’t take it if she knew where it came from. As a bar hostess, she is smart and coquettish, playing cute in a side not often seen from Kaji later in her career in order to get the punters to pay up, but unafraid to go all in that doesn’t work even pinching a construction worker’s truck as collateral when he refuses to pay his tab.

Nevertheless, the film subverts expectation by shifting away from the gambling movie model including only one round of cards which Nami easily wins and then immediately leaves explaining that you have to know when to quit in a fight or in gambling. The central conflict is, in fact, played out through an intense game of pool, a few brief moments of onscreen text explaining the rules before Nami squares off against a drug-addled Owada henchman whose face begins to glow in an ominous yellow as the stuff wears off. Nevertheless, when Owada reneges on his promises violence is all that remains. Nami and new friend Ryuji (Tsunehiko Watase) team up to take revenge on the sleazy gangsters in order to set Ginza to rights.

Nevertheless, there’s a kind of poignancy in the fact the central trio are all war orphans, “wandering birds” trying to find a foothold in the complicated post-war landscape while attempting to hold on to their sense of integrity. When Nami’s past as an ex-con is exposed to the other ladies at the bar they roundly reject her, though one assumes they’ve sad stories of their own, leaving her consumed by shame. Reformed by Saeko’s unexpected generosity of spirit and compassionate forgiveness, she bitterly regrets the moral compromises of her biker girl life and commits herself to fighting injustice, unwavering in her refusal to be complicit in the increasingly amoral venality of the post-war society. Sadly, Wandering Ginza Butterfly did not entirely succeed in stealing Fuji’s crown, the contemporary setting unable to overcome audience fatigue with the ninkyo genre which was shortly to implode in the wake of the jitsuroku revolution. It spawned only one sequel, but did perhaps pave the way for Kaji’s path to Toei stardom as the face of pinky violence.

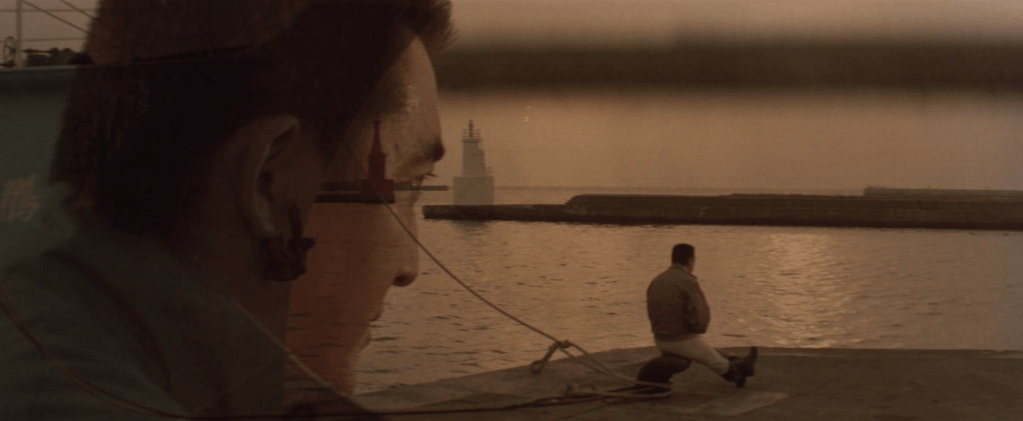

For one reason or another, the 1970s gave rise to a wave of disaster movies as Earthquakes devastated cities, high rise buildings caught fire, and ocean liners capsized. Japan wanted in on the action and so set about constructing its own culturally specific crisis movie. The central idea behind The Bullet Train (新幹線大爆破, Shinkansen Daibakuha) may well sound familiar as it was reappropriated for the 1994 smash hit and ongoing pop culture phenomenon Speed, but even if de Bont’s finely tuned rollercoaster was not exactly devoid of subversive political commentary The Bullet Train takes things one step further.

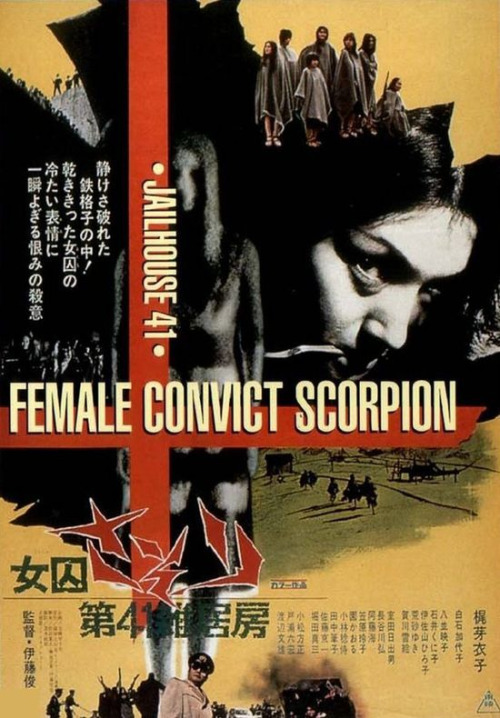

For one reason or another, the 1970s gave rise to a wave of disaster movies as Earthquakes devastated cities, high rise buildings caught fire, and ocean liners capsized. Japan wanted in on the action and so set about constructing its own culturally specific crisis movie. The central idea behind The Bullet Train (新幹線大爆破, Shinkansen Daibakuha) may well sound familiar as it was reappropriated for the 1994 smash hit and ongoing pop culture phenomenon Speed, but even if de Bont’s finely tuned rollercoaster was not exactly devoid of subversive political commentary The Bullet Train takes things one step further. Female Prisoner Scorpion: Jailhouse 41 (女囚さそり第41雑居房, Joshu Sasori – Dai 41 Zakkyobo) picks up around a year after the end of

Female Prisoner Scorpion: Jailhouse 41 (女囚さそり第41雑居房, Joshu Sasori – Dai 41 Zakkyobo) picks up around a year after the end of