Forced transfers have been in the news of late. Japanese companies, keen to attract and keep younger workers in the midst of a growing labour shortage, have been offering more modern working rights such as paid parental leave but also using them as increased leverage to force employees to take jobs in far flung places after returning to work – after all, you aren’t going to up and quit with a new baby to support.

Forced transfers have been in the news of late. Japanese companies, keen to attract and keep younger workers in the midst of a growing labour shortage, have been offering more modern working rights such as paid parental leave but also using them as increased leverage to force employees to take jobs in far flung places after returning to work – after all, you aren’t going to up and quit with a new baby to support.

As Isshin Inudo’s Samurai Shifters (引っ越し大名!, Hikkoshi Daimyo!) proves, contemporary corporate culture is not so different from the samurai ways of old. Back in the 17th century, the Shogun kept a tight grip on his power by shifting his lords round every so often in order to keep them on their toes. Seeing as they had to pay all the expenses and handle logistics themselves, relocating left a clan weakened and dangerously exposed which of course means they were unlikely to challenge the Shogun’s power and would be keen to keep his favour in order to avoid being asked to make regular moves to unprofitable places.

When the Echizen Matsudaira clan is ordered to move a considerable distance, crossing the sea to a new residence in Kyushu which isn’t even really a “castle”, they have a big problem because their previous relocation officer has passed away since their last move. Predictably, no one wants this totally thankless job which warrants seppuku if you mess it up so it falls to introverted librarian Harunosuke (Gen Hoshino) who is too shy refuse (even if he had much of a choice, which he doesn’t). Unfortunately for some, however, Harunosuke is both smart and kind which means he’s good at figuring out solutions to complicated problems and reluctant to exercise his samurai privilege to do so.

In fact Harunosuke is something of an odd samurai. As others later put it, he doesn’t care about status or seniority and has a natural tendency to treat everybody equally. When the head of accounts advises him to take loans from merchants with no intention to pay them back, he objects not only to the dishonesty but to the unfairness of stealing hard-earned money from ordinary people solely under the rationale that they are entitled to do so because they are samurai and therefore superior. Likewise, when he finds out that his predecessor was of a lower rank and that all his achievements were credited to his superiors he makes a point of going to his grave to apologise which earns him some brownie points with the man’s pretty daughter, Oran (Mitsuki Takahata), who was not previously minded to help him because of the way her father had been treated.

Harunosuke’s natural goodness begins to endear him to the jaded samurai now in his care. Though they might be suspicious of some of his methods including his “decluttering” program, they quickly come on board when they realise he is not intending to exclude himself from his ordinances and even consents to burn his own books in order to make it plain that everyone is in the same boat. He hesitates in his growing attraction to Oran (who in turn is also taken with him because of his atypical tendency to compassion) not only because of his natural diffidence but because he feels it might be selfish to pursue a romance while urging everyone else towards austerity.

Meanwhile, “romance” is why all this started in the first place. The lord, Naonori Matsudaira (Mitsuhiro Oikawa), is in a relationship with his steward (something which seems to be known to most and not particularly an issue). While he was in Edo, he rudely rebuffed the attentions of another lord, Yoshiyasu Yanagisawa (Osamu Mukai), who seems to have taken rejection badly and has it in for the clan as a whole. In an interesting role reversal, his advisor laments that perhaps it would have been better for everyone if he’d just submitted himself, but nevertheless a few thousand people are now affected by the petty romantic squabbles of elite samurai in far off Edo.

Bookish and reticent as he is, Harunosuke sees his chance to “go to war against the unjust Shogunate” by engineering a plan which allows them to reduce the burden of moving, reluctantly having to demote some samurai and leave them behind as ordinary farmers with the promise that they will be reinstated as soon as the clan resumes its former status. Asking the samurai to drop their superiority and carry their own bags for a change has profound implications for their society, but Harunosuke’s practical goodness eventually wins out as the clan comes together as one rather than obsessing over their petty internal divisions. A cheerful tale of homecoming, friendship, and warmhearted egalitarianism, Samurai Shifters is an oddly topical period comedy which satirises the vagaries of modern corporate culture through the prism of samurai-era mores but does so with a wry smile as Harunosuke finds a way to live within the system without compromising his principles and eventually wins all with little more than a compassionate heart and a finely tuned mind.

Samurai Shifters screens in New York on July 21 as part of Japan Cuts 2019.

Teaser trailer (English subtitles)

What would you give to live another day? What did you give to live this day? What did you take? Adapting the novel by Genki Kawamura, Akira Nagai takes a step back from the broad comedy of

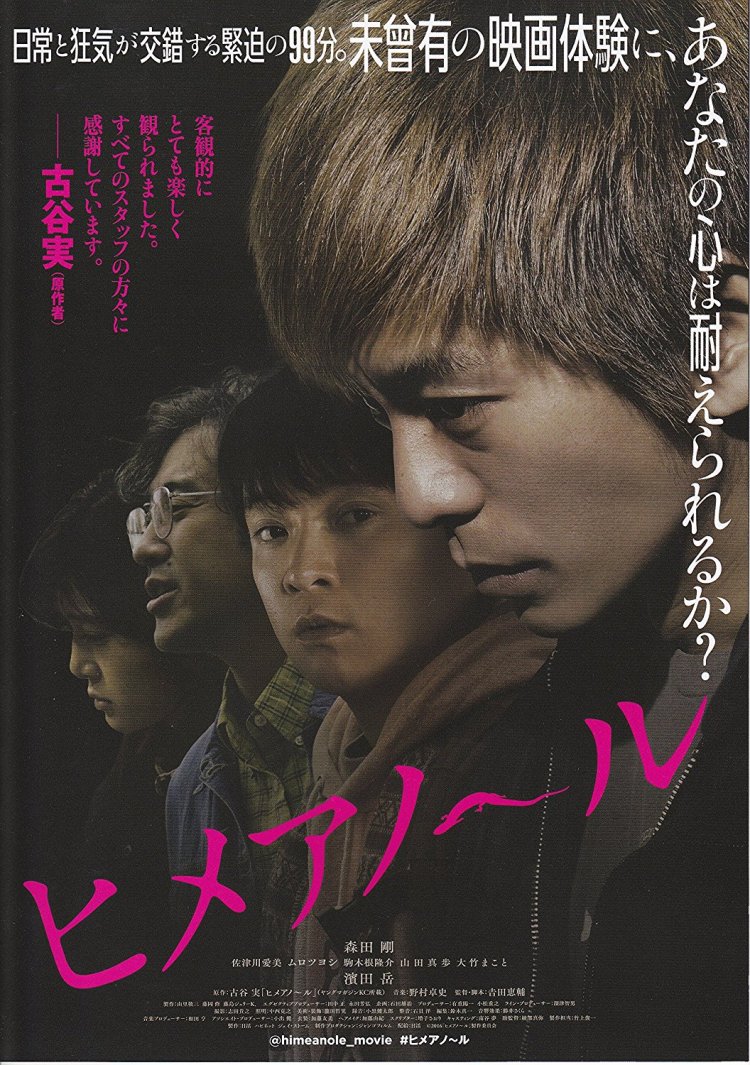

What would you give to live another day? What did you give to live this day? What did you take? Adapting the novel by Genki Kawamura, Akira Nagai takes a step back from the broad comedy of  Some people are odd, and that’s OK. Then there are the people who are odd, but definitely not OK. Hime-anole (ヒメアノ~ル) introduces us to both of these kinds of outsiders, attempting to draw a line between the merely awkward and the actively dangerous but ultimately finding that there is no line and perhaps simple acts of kindness offered at the right time could have prevented a mind snapping or a person descending into spiralling homicidal delusion. To go any further is to say too much, but Hime-anole revels in its reversals, switching rapidly between quirky romantic comedy, gritty Japanese indie, and finally grim social horror. Yet it plants its seeds early with two young men struggling to express their true emotions, trapped and lonely, leading unfulfilling lives. Their dissatisfaction is ordinary, but these same repressed emotions taken to an extreme can produce much more harmful results than two guys eating stale donuts everyday just to ask a pretty girl for the bill.

Some people are odd, and that’s OK. Then there are the people who are odd, but definitely not OK. Hime-anole (ヒメアノ~ル) introduces us to both of these kinds of outsiders, attempting to draw a line between the merely awkward and the actively dangerous but ultimately finding that there is no line and perhaps simple acts of kindness offered at the right time could have prevented a mind snapping or a person descending into spiralling homicidal delusion. To go any further is to say too much, but Hime-anole revels in its reversals, switching rapidly between quirky romantic comedy, gritty Japanese indie, and finally grim social horror. Yet it plants its seeds early with two young men struggling to express their true emotions, trapped and lonely, leading unfulfilling lives. Their dissatisfaction is ordinary, but these same repressed emotions taken to an extreme can produce much more harmful results than two guys eating stale donuts everyday just to ask a pretty girl for the bill. When Japan does musicals, even Hollywood style musicals, it tends to go for the backstage variety or a kind of hybrid form in which the idol/singing star protagonist gets a few snazzy numbers which somehow blur into the real world. Masayuki Suo’s previous big hit, Shall We Dance, took its title from the classic Rodgers and Hammerstein song featured in the King and I but it’s Lerner and Loewe he turns to for an American style song and dance fiesta relocating My Fair Lady to the world of Kyoto geisha, Lady Maiko (舞妓はレディ, Maiko wa Lady) . My Fair Lady was itself inspired by Shaw’s Pygmalion though replaces much of its class conscious, feminist questioning with genial romance. Suo’s take leans the same way but suffers somewhat in the inefficacy of its half hearted love story seeing as its heroine is only 15 years old.

When Japan does musicals, even Hollywood style musicals, it tends to go for the backstage variety or a kind of hybrid form in which the idol/singing star protagonist gets a few snazzy numbers which somehow blur into the real world. Masayuki Suo’s previous big hit, Shall We Dance, took its title from the classic Rodgers and Hammerstein song featured in the King and I but it’s Lerner and Loewe he turns to for an American style song and dance fiesta relocating My Fair Lady to the world of Kyoto geisha, Lady Maiko (舞妓はレディ, Maiko wa Lady) . My Fair Lady was itself inspired by Shaw’s Pygmalion though replaces much of its class conscious, feminist questioning with genial romance. Suo’s take leans the same way but suffers somewhat in the inefficacy of its half hearted love story seeing as its heroine is only 15 years old. There are few things in life which cannot at least be improved by a full and frank apology. Sometimes that apology will need to go beyond a simple, if heart felt, “I’m Sorry” to truly make amends but as long as there’s a genuine desire to make things right, it can be done. Some people do, however, need help in navigating this complex series of culturally defined rituals which is where the enterprising hero of Nobuo Mizuta’s The Apology King (謝罪の王様, Shazai no Ousama), Ryoro Kurojima (Sadao Abe), comes in. As head of the Tokyo Apology Centre, Kurojima is on hand to save the needy who find themselves requiring extrication from all kinds of sticky situations such as accidentally getting sold into prostitution by the yakuza or causing small diplomatic incidents with a tiny yet very angry foreign country.

There are few things in life which cannot at least be improved by a full and frank apology. Sometimes that apology will need to go beyond a simple, if heart felt, “I’m Sorry” to truly make amends but as long as there’s a genuine desire to make things right, it can be done. Some people do, however, need help in navigating this complex series of culturally defined rituals which is where the enterprising hero of Nobuo Mizuta’s The Apology King (謝罪の王様, Shazai no Ousama), Ryoro Kurojima (Sadao Abe), comes in. As head of the Tokyo Apology Centre, Kurojima is on hand to save the needy who find themselves requiring extrication from all kinds of sticky situations such as accidentally getting sold into prostitution by the yakuza or causing small diplomatic incidents with a tiny yet very angry foreign country. Yoshihiro Nakamura has made a name for himself as a master of fiendishly intricate, warm and quirky mysteries in which seemingly random events each radiate out from a single interconnected focus point. Golden Slumber (ゴールデンスランバー), like

Yoshihiro Nakamura has made a name for himself as a master of fiendishly intricate, warm and quirky mysteries in which seemingly random events each radiate out from a single interconnected focus point. Golden Slumber (ゴールデンスランバー), like  When it comes to the great Japanese artworks that everybody knows, the figure of Hokusai looms large. From the ubiquitous The Great Wave off Kanagawa to the infamous Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife, the work of Hokusai has come to represent the art of Edo woodblocks almost single handedly in the popular imagination yet there has long been scholarly debate about the true artist behind some of the pieces which are attributed to his name. Hokusai had a daughter – uniquely gifted, perhaps even surpassing the skills of her father, O-Ei was a talented artist in her own right as well as her father’s assistant and caregiver in his old age.

When it comes to the great Japanese artworks that everybody knows, the figure of Hokusai looms large. From the ubiquitous The Great Wave off Kanagawa to the infamous Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife, the work of Hokusai has come to represent the art of Edo woodblocks almost single handedly in the popular imagination yet there has long been scholarly debate about the true artist behind some of the pieces which are attributed to his name. Hokusai had a daughter – uniquely gifted, perhaps even surpassing the skills of her father, O-Ei was a talented artist in her own right as well as her father’s assistant and caregiver in his old age.