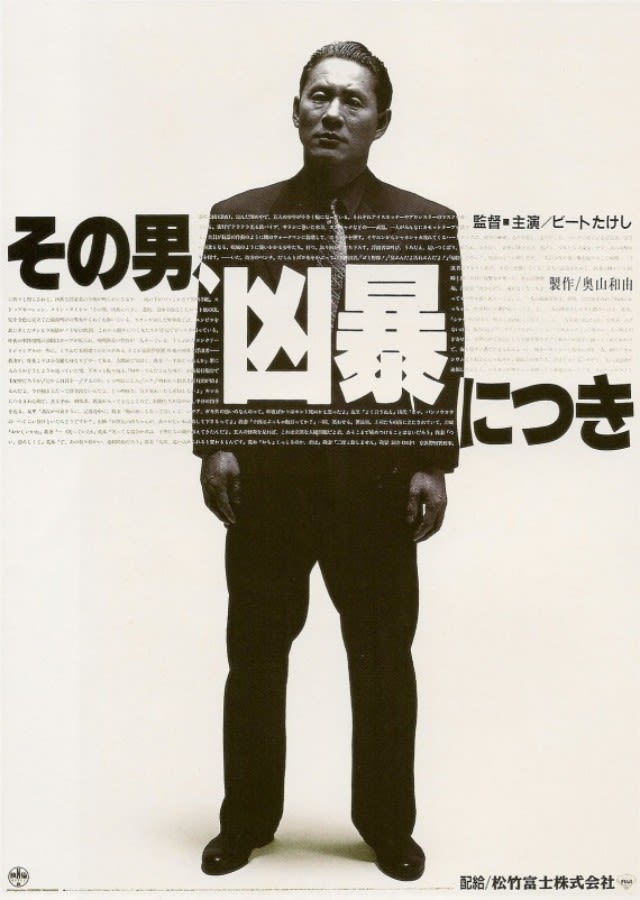

By and large, policemen in Japanese cinema are at least nominally a force for good. They may be bumbling and inefficient, occasionally idiotic and easily outclassed by a master detective, but are not generally depicted as actively corrupt or malicious. A notable exception would be within the films of Kinji Fukasaku whose jitsuroku gangster movies were never afraid to suggest that the line between thug and cop can be surprisingly thin. Fukasaku was originally slated to direct Violent Cop (その男、凶暴につき, Sono Otoko, Kyobo ni tsuki), casting top TV variety star “Beat” Takeshi in the title role in an adaptation of a hardboiled parody by Hisashi Nozawa. The project later fell apart due to Kitano’s heavy work schedule which eventually led to him directing the film himself, heavily rewriting the script in order to boil it down to its nihilistic essence while rejecting the broad comedy his TV fans would doubtless have been expecting.

Kitano’s trademark deadpan is, however, very much in evidence even in this his debut feature in which he struggled to convince a veteran crew to accept his idiosyncratic directorial vision. He opens not with the “hero”, but with a toothless old man, a hobo beset by petty delinquents so bored by the ease of their comfortable upperclass lives that they terrorise the less fortunate for fun. Azuma (Takeshi Kitano), the violent cop, does not approve but neither does he intervene, later explaining to his boss that it would have been foolish to do so without backup. Having observed from the shadows, he tails one of the boys to his well-appointed home, barges past his mother, and asks to have a word, immediately punching the kid in the face as soon as he opens the door. Rather than simply arrest him, he strongly encourages that he and his friends turn themselves in at the police station the next day or, he implies, expect more of the same. The kid complies.

Azuma embodies a certain kind of justice acting in direct opposition to the corruptions of the Bubble era which are indirectly responsible for the creation of these infinitely bored teens who live only for sadistic thrills. He arrives too late, however, to have any effect on the next generation, cheerfully smiling at a bunch of primary school children running off to play after throwing cans at an old man on a boat. Children always seem to be standing by, witnessing and absorbing violence from the world around them as when a fellow officer is badly assaulted by a suspect following Azuma’s botched attempt to arrest him in serial rather than parallel with his equally thuggish colleagues. But for all that Azuma’s violence is inappropriate for a man of the law, it is never condemned by his fellow officers who regard him only as slightly eccentric and a potential liability. Even his new boss on hearing of his reputation tells him that he doesn’t necessarily disapprove but would appreciate it if Azuma could avoid making the kind of trouble that would cause him inconvenience.

That’s obviously not going to happen. What we gradually realise is that Azuma may be in some ways the most sane of men or at least the most in tune with the world in which he lives, only losing his cool when a suspect spits back that he’s just as crazy as his sister who has recently been discharged from a psychiatric institution. Azuma has accepted that his world is defined by violence and no longer expects to be spared a violent end. He smirks ironically as he slaps his suspects, connecting with them on more than one level in indulging in the cosmic joke of existential battery. To Kitano, violence is cartoonish, unreal, and absurd. The only time the violence is shocking and seems as if it actually hurts is when it is visited directly on Azuma, the camera suddenly shifting into a quasi-PV shot as a foot strikes just below the frame. The targets are otherwise misdirected, a young woman caught by a stray bullet while waiting outside a cinema or a cop shot in the tussle over a gun, and again the children who only witness but are raised in the normalisation of violence.

Meanwhile, organised crime has attempted to subvert its violent image by adopting the trappings of the age, swapping post-war scrappiness for Bubble-era sophistication. Nito (Ittoku Kishibe), the big bad, has an entire floor as an office containing just his oversize desk and that of his secretary. These days, even gangsters have admin staff. Minimalist in the extreme with its plain white walls and spacious sense of emptiness, the office ought to be a peaceful space but the effect of its deliberately unstimulating decor is quite the reverse, intimidating and filled with anxiety. Behind Nito the ordinary office blinds look almost like prison bars. Meanwhile, the police locker room in much the same colours has a similarly claustrophobic quality, almost embodying a sense of violence as if the walls themselves are intensifying the pressure on all within them.

Azuma is indeed constrained, even while also the most “free” in having decided to live by his own codes in rejection of those offered by his increasingly corrupt society. He walks a dark and nihilistic path fuelled by the futility of violence, ending in a Hamlet-esque tableaux with only a dubious Fortinbras on hand to offer the ironic commentary that “they’re all mad”, before stepping neatly into another vacated space in willing collaboration with the systemic madness of the world in which he lives. With its incongruously whimsical score and deadpan humour Violent Cop never shies away from life’s absurdity, but has only a lyrical sadness for those seeking to numb the pain in a world of constant anxiety.

Violent Cop is the first of three films included in the BFI’s Takeshi Kitano Collection blu-ray box set and is accompanied by an audio commentary by Chris D recorded in 2008, plus a featurette recorded in 2016. The first pressing includes a 44-page booklet featuring an essay on Violent Cop by Tom Mes, as well as an introduction to Kitano’s career & writing on Sonatine by Jasper Sharp, a piece on Boiling Point from Mark Schilling, an archival review by Geoff Andrew, and an appreciation of Beat Takeshi by James-Masaki Ryan.

The Takeshi Kitano Collection is released 29th June while Violent Cop, Boiling Point, and Sonatine will also be available to stream via BFI Player from 27th July as part of BFI Japan.

Original trailer (English subtitles)

Times change so quickly. The “danchi” was a symbol of post-war aspiration and rising economic prosperity as it sought to give young professionals an affordable yet modern, convenient way of life. The term itself is a little hard to translate though loosely enough just means a housing estate but unlike “The Projects” (団地, Danchi) of the title, these are generally not areas of social housing or lower class neighbourhoods but a kind of vertical village which one should never need to leave (except to go to work) as they also include all the necessary amenities for everyday life from shops and supermarkets to bars and restaurants. Nevertheless, aspirations change across generations and what was once considered a dreamlike promise of futuristic convenience now seems run down and squalid. Cramped apartments with tiny rooms, washing machines on the balconies, no lifts – young people do not see these things as convenient and so the danchi is mostly home to the older generation, downsizers, or the down on their luck.

Times change so quickly. The “danchi” was a symbol of post-war aspiration and rising economic prosperity as it sought to give young professionals an affordable yet modern, convenient way of life. The term itself is a little hard to translate though loosely enough just means a housing estate but unlike “The Projects” (団地, Danchi) of the title, these are generally not areas of social housing or lower class neighbourhoods but a kind of vertical village which one should never need to leave (except to go to work) as they also include all the necessary amenities for everyday life from shops and supermarkets to bars and restaurants. Nevertheless, aspirations change across generations and what was once considered a dreamlike promise of futuristic convenience now seems run down and squalid. Cramped apartments with tiny rooms, washing machines on the balconies, no lifts – young people do not see these things as convenient and so the danchi is mostly home to the older generation, downsizers, or the down on their luck. When Japan does musicals, even Hollywood style musicals, it tends to go for the backstage variety or a kind of hybrid form in which the idol/singing star protagonist gets a few snazzy numbers which somehow blur into the real world. Masayuki Suo’s previous big hit, Shall We Dance, took its title from the classic Rodgers and Hammerstein song featured in the King and I but it’s Lerner and Loewe he turns to for an American style song and dance fiesta relocating My Fair Lady to the world of Kyoto geisha, Lady Maiko (舞妓はレディ, Maiko wa Lady) . My Fair Lady was itself inspired by Shaw’s Pygmalion though replaces much of its class conscious, feminist questioning with genial romance. Suo’s take leans the same way but suffers somewhat in the inefficacy of its half hearted love story seeing as its heroine is only 15 years old.

When Japan does musicals, even Hollywood style musicals, it tends to go for the backstage variety or a kind of hybrid form in which the idol/singing star protagonist gets a few snazzy numbers which somehow blur into the real world. Masayuki Suo’s previous big hit, Shall We Dance, took its title from the classic Rodgers and Hammerstein song featured in the King and I but it’s Lerner and Loewe he turns to for an American style song and dance fiesta relocating My Fair Lady to the world of Kyoto geisha, Lady Maiko (舞妓はレディ, Maiko wa Lady) . My Fair Lady was itself inspired by Shaw’s Pygmalion though replaces much of its class conscious, feminist questioning with genial romance. Suo’s take leans the same way but suffers somewhat in the inefficacy of its half hearted love story seeing as its heroine is only 15 years old. Hideo Gosha maybe best known for the “manly way” movies of his early career in which angry young men fought for honour and justice, but mostly just to to survive. Late into his career, Gosha decided to change tack for a while with a series of female orientated films either remaining within the familiar gangster genre as in Yakuza Wives, or shifting into world of the red light district as in Tokyo Bordello (吉原炎上, Yoshiwara Enjo). Presumably an attempt to get past the unfamiliarity of the Yoshiwara name, the film’s English title is perhaps a little more obviously salacious than the original Japanese which translates as Yoshiwara Conflagration and directly relates to the real life fire of 1911 in which 300 people were killed and much of the area razed to the ground. Gosha himself grew up not far from the location of the Yoshiwara as it existed in the mid-20th century where it was still a largely lower class area filled with cardsharps, yakuza, and, yes, prostitution (legal in Japan until 1958, outlawed in during the US occupation). The Yoshiwara of the late Meiji era was not so different as the women imprisoned there suffered at the hands of men, exploited by a cruelly misogynistic social system and often driven mad by internalised rage at their continued lack of agency.

Hideo Gosha maybe best known for the “manly way” movies of his early career in which angry young men fought for honour and justice, but mostly just to to survive. Late into his career, Gosha decided to change tack for a while with a series of female orientated films either remaining within the familiar gangster genre as in Yakuza Wives, or shifting into world of the red light district as in Tokyo Bordello (吉原炎上, Yoshiwara Enjo). Presumably an attempt to get past the unfamiliarity of the Yoshiwara name, the film’s English title is perhaps a little more obviously salacious than the original Japanese which translates as Yoshiwara Conflagration and directly relates to the real life fire of 1911 in which 300 people were killed and much of the area razed to the ground. Gosha himself grew up not far from the location of the Yoshiwara as it existed in the mid-20th century where it was still a largely lower class area filled with cardsharps, yakuza, and, yes, prostitution (legal in Japan until 1958, outlawed in during the US occupation). The Yoshiwara of the late Meiji era was not so different as the women imprisoned there suffered at the hands of men, exploited by a cruelly misogynistic social system and often driven mad by internalised rage at their continued lack of agency. After completing his first “Onomichi Trilogy” in the 1980s, Obayashi returned a decade later for round two with another three films using his picturesque home town as a backdrop. Goodbye For Tomorrow (あした, Ashita) is the second of these, but unlike Chizuko’s Younger Sister or One Summer’s Day which both return to Obayashi’s concern with youth, Goodbye For Tomorrow casts its net a little wider as it explores the grief stricken inertia of a group of people from all ages and backgrounds left behind when a routine ferry journey turns into an unexpected tragedy.

After completing his first “Onomichi Trilogy” in the 1980s, Obayashi returned a decade later for round two with another three films using his picturesque home town as a backdrop. Goodbye For Tomorrow (あした, Ashita) is the second of these, but unlike Chizuko’s Younger Sister or One Summer’s Day which both return to Obayashi’s concern with youth, Goodbye For Tomorrow casts its net a little wider as it explores the grief stricken inertia of a group of people from all ages and backgrounds left behind when a routine ferry journey turns into an unexpected tragedy. Miss Lonely (さびしんぼう, Sabishinbou, AKA Lonelyheart) is the final film in Obayashi’s Onomichi Trilogy all of which are set in his own hometown of Onomichi. This time Obayashi casts up and coming idol of the time, Yasuko Tomita, in a dual role of a reserved high school student and a mysterious spirit known as Miss Lonely. In typical idol film fashion, Tomita also sings the theme tune though this is a much more male lead effort than many an idol themed teen movie.

Miss Lonely (さびしんぼう, Sabishinbou, AKA Lonelyheart) is the final film in Obayashi’s Onomichi Trilogy all of which are set in his own hometown of Onomichi. This time Obayashi casts up and coming idol of the time, Yasuko Tomita, in a dual role of a reserved high school student and a mysterious spirit known as Miss Lonely. In typical idol film fashion, Tomita also sings the theme tune though this is a much more male lead effort than many an idol themed teen movie.