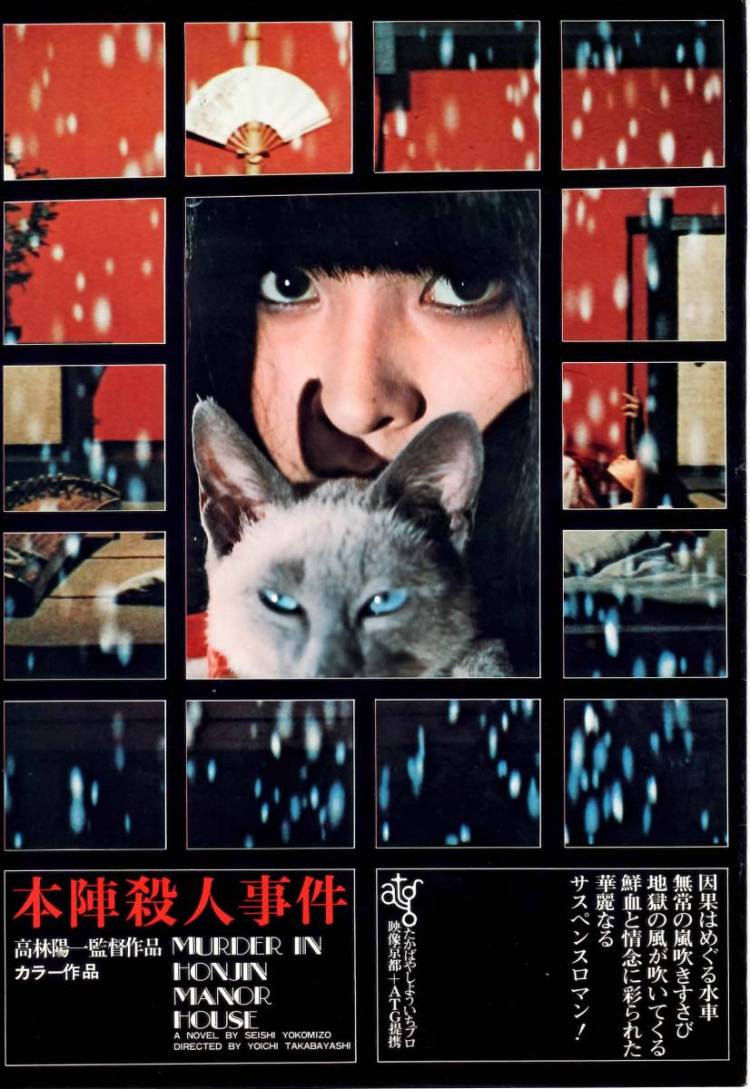

Kousuke Kindaichi is one of the best known detectives of Japanese literature. There are 77 books in the Kindaichi series which has spawned numerous cinematic adaptations as well as a popular manga and anime spin-off starring the grandson of the original sleuth. Sadly only one of Seishi Yokomizo’s novels has been translated into English (The Inugami Clan which has the distinction of having been filmed not once but twice by Kon Ichikawa), but many Japanese mystery lovers have ranked his debut, The Murder in the Honjin, as one of the best locked room mysteries ever written. Starring Akira Nakao as the eccentric detective, Yoichi Takabayashi’s Death at an Old Mansion (本陣殺人事件, Honjin Satsujin Jiken) was the first of three films he’d make for The Art Theatre Guild of Japan and updates the 1937 setting of Yokomizu’s novel to the contemporary 1970s.

Kousuke Kindaichi is one of the best known detectives of Japanese literature. There are 77 books in the Kindaichi series which has spawned numerous cinematic adaptations as well as a popular manga and anime spin-off starring the grandson of the original sleuth. Sadly only one of Seishi Yokomizo’s novels has been translated into English (The Inugami Clan which has the distinction of having been filmed not once but twice by Kon Ichikawa), but many Japanese mystery lovers have ranked his debut, The Murder in the Honjin, as one of the best locked room mysteries ever written. Starring Akira Nakao as the eccentric detective, Yoichi Takabayashi’s Death at an Old Mansion (本陣殺人事件, Honjin Satsujin Jiken) was the first of three films he’d make for The Art Theatre Guild of Japan and updates the 1937 setting of Yokomizu’s novel to the contemporary 1970s.

Beginning at the end, Kindaichi (Akira Nakao) arrives at a country mansion with a sense of foreboding which borne out when he realises that the young lady he’s come to see, Suzu (Junko Takazawa), has died and he’s arrived just in time to witness her funeral. It’s been a year since he first met her, though he did so under less than ideal circumstances. As it happened, Suzu’s older brother, Kenzo (Takahiro Tamura), was married to a young woman of his own choosing, Katsuko (Yuki Mizuhara), despite strong familial opposition. On the night of their wedding, the couple were brutally murdered inside a private annex to the main building. The doors were firmly locked from the inside and there was no murder weapon on site. The only clue was bloody three fingered handprint made by someone wearing the “tsume” or picks used for playing the koto. Kindaichi, already a well known private detective, was summoned to investigate because of a personal connection to Katsuko’s uncle, Ginzo (Kunio Kaga).

The original novel was published in 1946 and it has to be said, some of its themes make more sense in the pre-war 1937 setting than they do for the comparatively more liberal one of 1975 though such small minded attitudes are hardly uncommon even in the world today. The Ichiyanagi family live on a large family estate (apparently not the “Honjin” – a resting place for imperial retinues in the Edo era, of the title but the ancestral association remains) and enjoy a degree of social standing as well as the privilege of wealth in the small rural town. Katsuko, by contrast, is from a “lowly” family of well-to-do farmers – mere peasantry to the Ichiyanagis, many of whom believe Kenzo is making a huge and embarrassing mistake in his choice of wife. Kenzo, a middle-aged scholar, has shocked them all with his sudden determination to marry, not to mention his determination to break with family protocol and marry beneath him.

Japanese mysteries are much less concerned with motive than their Western counterparts, but class conflict is definitely offered as a possible reason for murder. Other clues have more menacing dimensions such as the repeated mentions of a scary looking three fingered man who apparently delivered a threatening letter to the mansion on the night of the murder, and Suzu’s constant questions about her recently deceased cat who liked to listen to her play the koto. Suzu is 17 but has some kind of learning difficulties and is arrested in a childlike state of innocence which leads her to utter simple yet profound words of wisdom whilst also believing that her recently deceased cat, Tama, is some kind of god. Suzu’s “innocence” is contrasted with her brother’s coldhearted rigidity in which he’s described as a sanctimonious snob who believes himself above regular folk and treats his servants with contempt. This same rigidity in fact aligns him with his sister as both share an “atypical” way of thought and behaviour. Kenzo’s unexpected romance turns out not to be middle-aged lust for domination but an innocent first love arriving at 40 with all the pain and complication of adolescence.

Kindaichi arrives to solve the crime and makes an instant partner of the police inspector in charge who’s glad to have such esteemed help on such a difficult case. Putting two and two together, Kindaichi soon comes up with a few ideas after rubbing up against a mystery novel obsessed suspect and numerous red herrings. Once again coincidence plays a huge role, but the business of the murder is certainly elaborate given the pettiness of the reasoning behind it. Takabayashi never plays down the typically generic elements of this classic mystery, but adds to them with eerie, occasionally psychedelic camera work, shifting to sepia for imagined reconstructions and making use of repeated motifs from the fire-like imagery of the water wheel to a shattered photo of Kenzo shot through the eye. Strangely framed in red and gold the murder takes on a theatrical association that’s perfectly in keeping with its well choreographed genesis, and all the more chilling because of it. A satisfying locked room mystery, Death at an Old Mansion is also a tragedy of out dated ideals equated with a kind of innocence and purity, of those who couldn’t allow their dreams to be sullied or their name besmirched. Perhaps not so different from the world of 1937 after all.

Original trailer (no subtitles)

Still most closely associated with his debut feature Hausu – a psychedelic haunted house musical, Nobuhiko Obayashi’s affinity for youthful subjects made him a great fit for the burgeoning Kadokawa idol phenomenon. Maintaining his idiosyncratic style, Obayashi worked extensively in the idol arena eventually producing such well known films as

Still most closely associated with his debut feature Hausu – a psychedelic haunted house musical, Nobuhiko Obayashi’s affinity for youthful subjects made him a great fit for the burgeoning Kadokawa idol phenomenon. Maintaining his idiosyncratic style, Obayashi worked extensively in the idol arena eventually producing such well known films as  You might think there could be no more diametrically opposed directors than Akira Kurosawa – best known for his naturalistic (by jidaigeki standards anyway) three hour epic Seven Samurai, and Nobuhiko Obayashi whose madcap, psychedelic, horror musical Hausu continues to over shadow a far less strange career than might be expected. However,

You might think there could be no more diametrically opposed directors than Akira Kurosawa – best known for his naturalistic (by jidaigeki standards anyway) three hour epic Seven Samurai, and Nobuhiko Obayashi whose madcap, psychedelic, horror musical Hausu continues to over shadow a far less strange career than might be expected. However,  Nobuhiko Obayashi is no stranger to a ghost story whether literal or figural but never has his pre-occupation with being pre-occupied about the past been more delicately expressed than in his 1988 horror-tinged supernatural adventure, The Discarnates (異人たちとの夏, Ijintachi to no Natsu). Nostalgia is a central pillar of Obayashi’s world, as drenched in melancholy as it often is, but it can also be pernicious – an anchor which pins a person in a certain spot and forever impedes their progress.

Nobuhiko Obayashi is no stranger to a ghost story whether literal or figural but never has his pre-occupation with being pre-occupied about the past been more delicately expressed than in his 1988 horror-tinged supernatural adventure, The Discarnates (異人たちとの夏, Ijintachi to no Natsu). Nostalgia is a central pillar of Obayashi’s world, as drenched in melancholy as it often is, but it can also be pernicious – an anchor which pins a person in a certain spot and forever impedes their progress. After completing his first “Onomichi Trilogy” in the 1980s, Obayashi returned a decade later for round two with another three films using his picturesque home town as a backdrop. Goodbye For Tomorrow (あした, Ashita) is the second of these, but unlike Chizuko’s Younger Sister or One Summer’s Day which both return to Obayashi’s concern with youth, Goodbye For Tomorrow casts its net a little wider as it explores the grief stricken inertia of a group of people from all ages and backgrounds left behind when a routine ferry journey turns into an unexpected tragedy.

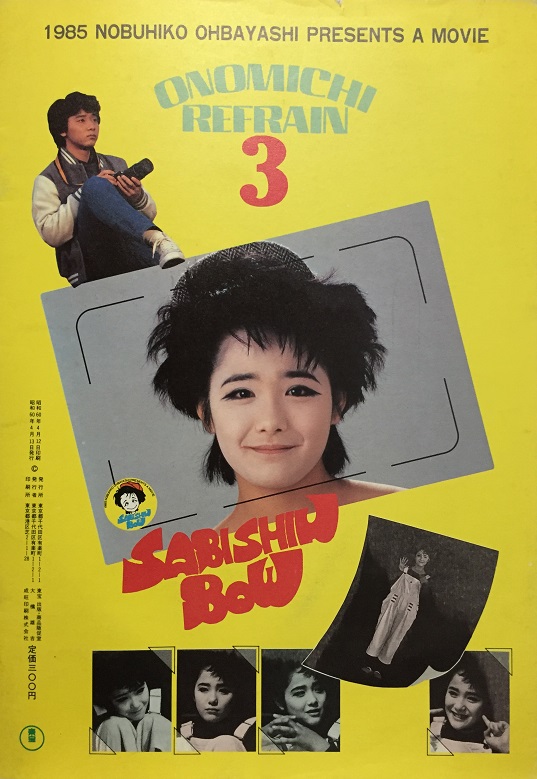

After completing his first “Onomichi Trilogy” in the 1980s, Obayashi returned a decade later for round two with another three films using his picturesque home town as a backdrop. Goodbye For Tomorrow (あした, Ashita) is the second of these, but unlike Chizuko’s Younger Sister or One Summer’s Day which both return to Obayashi’s concern with youth, Goodbye For Tomorrow casts its net a little wider as it explores the grief stricken inertia of a group of people from all ages and backgrounds left behind when a routine ferry journey turns into an unexpected tragedy. Miss Lonely (さびしんぼう, Sabishinbou, AKA Lonelyheart) is the final film in Obayashi’s Onomichi Trilogy all of which are set in his own hometown of Onomichi. This time Obayashi casts up and coming idol of the time, Yasuko Tomita, in a dual role of a reserved high school student and a mysterious spirit known as Miss Lonely. In typical idol film fashion, Tomita also sings the theme tune though this is a much more male lead effort than many an idol themed teen movie.

Miss Lonely (さびしんぼう, Sabishinbou, AKA Lonelyheart) is the final film in Obayashi’s Onomichi Trilogy all of which are set in his own hometown of Onomichi. This time Obayashi casts up and coming idol of the time, Yasuko Tomita, in a dual role of a reserved high school student and a mysterious spirit known as Miss Lonely. In typical idol film fashion, Tomita also sings the theme tune though this is a much more male lead effort than many an idol themed teen movie. Nobuhiko Obayashi takes another trip into the idol movie world only this time for Toho with an adaptation of a popular shojo manga. That is to say, he employs a number of idols within the film led by Toho’s own Yasuko Sawaguchi, though the film does not fit the usual idol movie mould in that neither Sawaguchi or the other girls is linked with the title song. Following something of a sisterly trope which is not uncommon in Japanese film or literature, Four Sisters (姉妹坂, Shimaizaka) centres around four orphaned children who discover their pasts, and indeed futures, are not necessarily those they would have assumed them to be.

Nobuhiko Obayashi takes another trip into the idol movie world only this time for Toho with an adaptation of a popular shojo manga. That is to say, he employs a number of idols within the film led by Toho’s own Yasuko Sawaguchi, though the film does not fit the usual idol movie mould in that neither Sawaguchi or the other girls is linked with the title song. Following something of a sisterly trope which is not uncommon in Japanese film or literature, Four Sisters (姉妹坂, Shimaizaka) centres around four orphaned children who discover their pasts, and indeed futures, are not necessarily those they would have assumed them to be. The Girl Who Leapt Through Time is a perennial favourite in its native Japan. Yasutaka Tsutsui’s original novel was first published back in 1967 giving rise to a host of multimedia incarnations right up to the present day with Mamoru Hosoda’s 2006 animated film of the same name which is actually a kind of sequel to Tsutsui’s story. Arguably among the best known, or at least the best loved to a generation of fans, is Hausu director Nobuhiko Obayashi’s 1983 movie The Little Girl Who Conquered Time (時をかける少女, Toki wo Kakeru Shoujo) which is, once again, a Kadokawa teen idol flick complete with a music video end credits sequence.

The Girl Who Leapt Through Time is a perennial favourite in its native Japan. Yasutaka Tsutsui’s original novel was first published back in 1967 giving rise to a host of multimedia incarnations right up to the present day with Mamoru Hosoda’s 2006 animated film of the same name which is actually a kind of sequel to Tsutsui’s story. Arguably among the best known, or at least the best loved to a generation of fans, is Hausu director Nobuhiko Obayashi’s 1983 movie The Little Girl Who Conquered Time (時をかける少女, Toki wo Kakeru Shoujo) which is, once again, a Kadokawa teen idol flick complete with a music video end credits sequence. Like many directors during the 1980s, Nobuhiko Obayashi was unable to resist the lure of a Kadokawa teen movie but His Motorbike, Her Island (彼のオートバイ彼女の島, Kare no Ootobai, Kanojo no Shima) is a typically strange 1950s throwback with its tale of motorcycle loving youngsters and their ennui filled days. Switching between black and white and colour, Obayashi paints a picture of a young man trapped in an eternal summer from which he has no desire to escape.

Like many directors during the 1980s, Nobuhiko Obayashi was unable to resist the lure of a Kadokawa teen movie but His Motorbike, Her Island (彼のオートバイ彼女の島, Kare no Ootobai, Kanojo no Shima) is a typically strange 1950s throwback with its tale of motorcycle loving youngsters and their ennui filled days. Switching between black and white and colour, Obayashi paints a picture of a young man trapped in an eternal summer from which he has no desire to escape.