The Taisho era was, like that of the post-war, a time both of confusion and possibility in which the young, in particular, looked for new paths and new freedoms as the world got wider and ideas flowed in from every corner of the globe. In The Love of the Actress Sumako (女優須磨子の恋, Joyu Sumako no koi), the second of a loose trilogy films about female emancipation, Kenji Mizoguchi took the real life story of a pioneering actress of Western theatre and used it to explore the progress of lack there of in terms of social freedoms not only for women but for artists and for society as a whole.

The Taisho era was, like that of the post-war, a time both of confusion and possibility in which the young, in particular, looked for new paths and new freedoms as the world got wider and ideas flowed in from every corner of the globe. In The Love of the Actress Sumako (女優須磨子の恋, Joyu Sumako no koi), the second of a loose trilogy films about female emancipation, Kenji Mizoguchi took the real life story of a pioneering actress of Western theatre and used it to explore the progress of lack there of in terms of social freedoms not only for women but for artists and for society as a whole.

We begin in late Meiji as theatre director Shimamura (So Yamamura) fights to establish a foothold of Western-style “art theatre”, moving away from the theatricality of kabuki for something more immediate and naturalistic. He has, however, a problem in that as women were not allowed to take to the kabuki stage all of his students are male and casting a man to play a woman’s role would run counter to his desires to create a truly representative theatre. It is therefore lucky that he runs into Sumako Matsui (Kinuyo Tanaka) – a feisty, determined young woman who had divorced her first husband for infidelity and then left the second when he complained about her desire to pursue a career on the stage. In Sumako, Shimamura finds a muse and the ideal woman to portray the extremely controversial figure of Nora in his dream production of Ibsen’s incendiary A Doll’s House.

Shimamura casts Sumako because he sees in her some of Nora’s defiance and eventual desire to be free from illusionary social constraints, but it is in fact he who ends up embodying her spirit in real life. Somewhat feminised, Shimamura is in a difficult position in having married into his wife’s family, leaving him without real agency inside his own home as evidenced by his mild opposition to his daughter’s arranged marriage. While he wishes that his daughter be happy and if possible marry for love, Shimamura’s wife is very much of the old school and wants to make the best possible match in terms of financial gain and social status, viewing emotional compatibility as a low priority (the daughter herself as relatively little say). Unwisely falling in love with Sumako, it is he who eventually decides to follow Nora’s example by walking out not only on his family but also on the theatre company. He does this not quite because the scales have been lifted from his eyes – he was never under any illusion that his arranged marriage was “real” and there is of course an accepted degree of performance involved in all such unions, but because he finally sees possibility enough in his love for Sumako and the viability of emotionally honest Western art to allow him to break free of outdated feudal ideas of familial obligation.

Nevertheless, making a career as an artist is a difficult prospect in any age and Shimamura’s emotional freedom quickly becomes tied up with that of his art. Sumako’s Nora proves a hit (in the last year of Meiji), but he is ahead of his times both in terms of his liberal, left-wing philosophy and his determination to embrace modern drama in a still traditional society. The roles we see Sumako perform, including that in Tolstoy’s Resurrection which was another of those that helped to make her name, are all from proto-feminist plays which revolve around women who, like herself, had chosen to challenge the patriarchal status quo in pursuit of their own freedom and agency. Shimamura’s wife makes no secret of her outrage to her husband’s desire to stage A Doll’s House, viewing Nora’s decision as “selfish” and perhaps of a subversion of every notion she associates with idealised femininity. Though not so far apart in age, Sumako is a woman of Taisho who left not one but two unfulfilling marriages and is determined to forge her own path even if that path eventually leads her to subsume her own desires within those of her lover as the pair attempt to put their social revolution on the stage.

The revolution, however, does not quite take off. Despite good early notices, Shimamura’s Art Theatre company quickly runs into trouble. Faced with financial ruin, he does what any sensible theatre producer would do – he begins to prioritise bums on seats and acknowledges that if he’s to keep his company afloat and facilitate his dream of making Western theatre a success in Japan he’ll have to compromise his artistic aims by putting on some populist plays. Of course, this sudden concession to commercial demands does not go down well with all and some of his hardline actors begin to leave in protest not just of his selling out but of his twinned desire to make Sumako his star.

Tellingly, the pair are eventually forced out of Japan entirely to tour the beginnings of empire from Korea to China and on to Taiwan. Their ideas are too radical and their society not quite ready for their messages even if not initially as hostile as it would later become. Shimamura works himself to the bone trying to keep his dream alive, eventually damaging his health. Sumako remains somewhat petulant about being forced into an itinerant lifestyle while her onstage personas come increasingly to influence her offstage life until it is said of her that her performance is “no longer an interpretation but an extension of reality”. In this, Sumako has, in a sense, achieved Shimamura’s dreams of a truly naturalistic theatre, but it comes at a cost, as perhaps all art does, and, Mizoguchi seems to suggest, becomes a kind of sacrifice laid down to a society still too rigid and unforgiving to appreciate its sincerity. Nevertheless, their boldness, as fruitless as it was, has started a flame which others intend to keep burning, eventually becoming a beacon for another new world looking to rebuild itself better and freer than before.

Short clip featuring Sumako’s performance as Carmen.

Junichiro Tanizaki is widely regarded as one of the major Japanese literary figures of the twentieth century with his work frequently adapted for the cinema screen. Those most familiar with Kon Ichikawa’s art house leaning pictures such as war films The Burmese Harp or Fires on the Plain might find it quite an odd proposition but in many ways, there could be no finer match for Tanizaki’s subversive, darkly comic critiques of the baser elements of human nature than the otherwise wry director. Odd Obsession (鍵, Kagi) may be a strange title for this adaptation of Tanizaki’s well known later work The Key, but then again “odd obsessions” is good way of describing the majority of Tanizaki’s career. A tale of destructive sexuality, the odd obsession here is not so much pleasure or even dominance but a misplaced hope of sexuality as salvation, that the sheer force of stimulation arising from desire can in some way be harnessed to stave off the inevitable even if it entails a kind of personal abstinence.

Junichiro Tanizaki is widely regarded as one of the major Japanese literary figures of the twentieth century with his work frequently adapted for the cinema screen. Those most familiar with Kon Ichikawa’s art house leaning pictures such as war films The Burmese Harp or Fires on the Plain might find it quite an odd proposition but in many ways, there could be no finer match for Tanizaki’s subversive, darkly comic critiques of the baser elements of human nature than the otherwise wry director. Odd Obsession (鍵, Kagi) may be a strange title for this adaptation of Tanizaki’s well known later work The Key, but then again “odd obsessions” is good way of describing the majority of Tanizaki’s career. A tale of destructive sexuality, the odd obsession here is not so much pleasure or even dominance but a misplaced hope of sexuality as salvation, that the sheer force of stimulation arising from desire can in some way be harnessed to stave off the inevitable even if it entails a kind of personal abstinence.

These days, cats may have almost become a cute character cliche in Japanese pop culture, but back in the olden days they weren’t always so well regarded. An often overlooked subset of the classic Japanese horror movie is the ghost cat film in which a demonic, shapeshifting cat spirit takes a beautiful female form to wreak havoc on the weak and venal human race. The most well known example is Kaneto Shindo’s Kuroneko though the genre runs through everything from ridiculous schlock to high grade art film.

These days, cats may have almost become a cute character cliche in Japanese pop culture, but back in the olden days they weren’t always so well regarded. An often overlooked subset of the classic Japanese horror movie is the ghost cat film in which a demonic, shapeshifting cat spirit takes a beautiful female form to wreak havoc on the weak and venal human race. The most well known example is Kaneto Shindo’s Kuroneko though the genre runs through everything from ridiculous schlock to high grade art film.

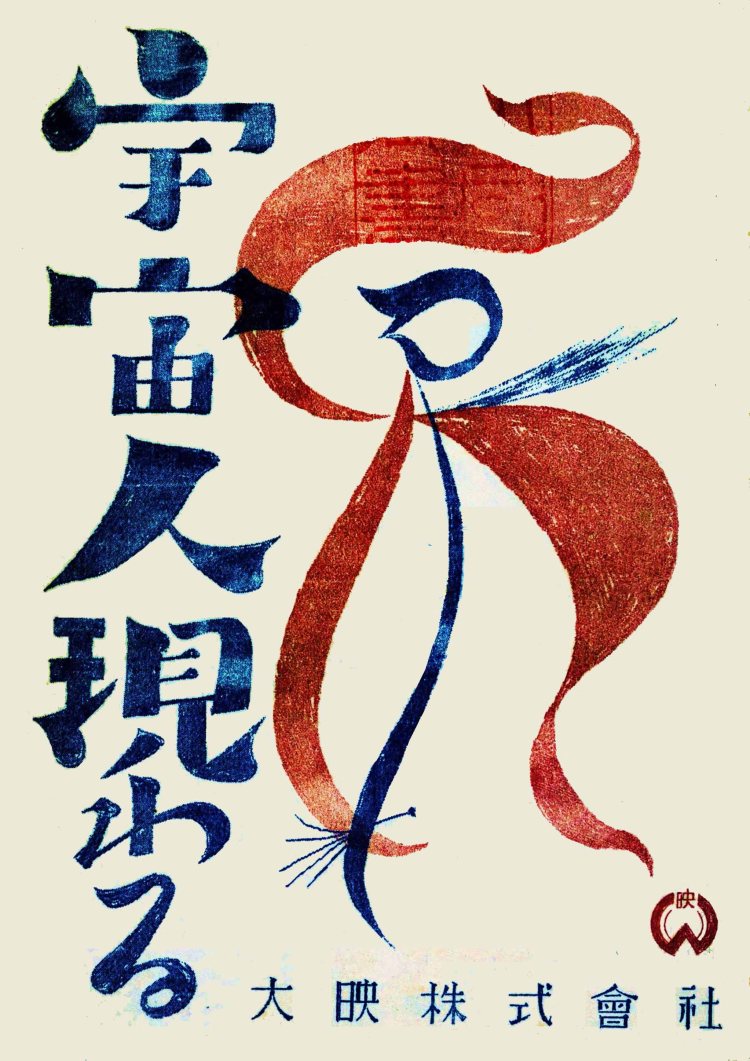

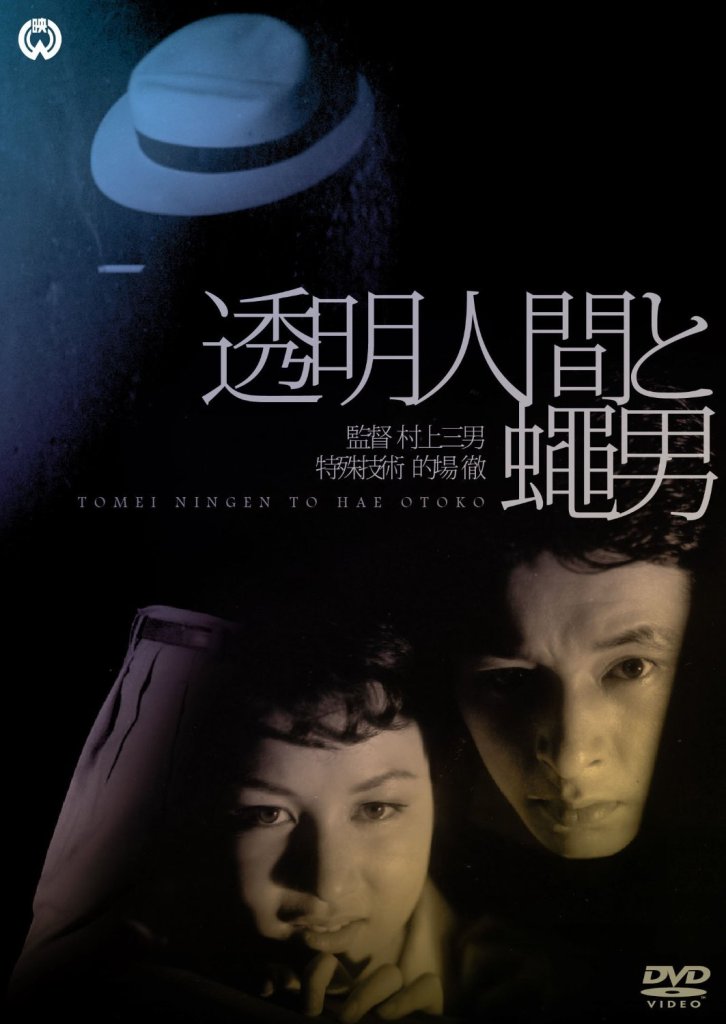

Who would win in a fight between The Invisible Man and The Human Fly? Well, when you think about it, the answer’s sort of obvious and how funny it would be to watch probably depends on your ability to detect the facial expressions of The Human Fly, but nevertheless Daiei managed to make an entire film out of this concept which is a sort of late follow-up to their original take on

Who would win in a fight between The Invisible Man and The Human Fly? Well, when you think about it, the answer’s sort of obvious and how funny it would be to watch probably depends on your ability to detect the facial expressions of The Human Fly, but nevertheless Daiei managed to make an entire film out of this concept which is a sort of late follow-up to their original take on

Released in 1949, The Invisible Man Appears (透明人間現る, Toumei Ningen Arawaru) is the oldest extant Japanese science fiction film. Loosely based on the classic HG Wells story The Invisible Man but taking its cues from the various Hollywood adaptations most prominently the Claude Rains version from 1933, The Invisible Man Appears also adds a hearty dose of moral guidance when it comes to scientific research.

Released in 1949, The Invisible Man Appears (透明人間現る, Toumei Ningen Arawaru) is the oldest extant Japanese science fiction film. Loosely based on the classic HG Wells story The Invisible Man but taking its cues from the various Hollywood adaptations most prominently the Claude Rains version from 1933, The Invisible Man Appears also adds a hearty dose of moral guidance when it comes to scientific research. Irezumi (刺青) is one of three films completed by the always prolific Yasuzo Masumura in 1966 alone and, though it stars frequent collaborator Ayako Wakao, couldn’t be more different than the actresses’ other performance for the director that year, the wartime drama

Irezumi (刺青) is one of three films completed by the always prolific Yasuzo Masumura in 1966 alone and, though it stars frequent collaborator Ayako Wakao, couldn’t be more different than the actresses’ other performance for the director that year, the wartime drama