Though Goemon might have thought himself free of his ninja past at the conclusion of the first film, he was unfortunately mistaken. Shinobi no Mono 2: Vengeance (続・忍びの者, Zoku Shinobi no Mono) sees him trying to live quietly with Maki and their son in a cabin in the woods, but Nobunaga is more powerful than ever. He’s wiped out the Iga ninja and is currently hunting down stragglers. Try as he might, what Goemon discovers the impossibility of living outside of the chaos of the feudal era.

After he’s caught and suffers a family tragedy, Goemon and Maki (Shiho Fujimura) move to her home village in Saiga which is the last refuge of the Ikko rebels who oppose Nobunaga. This time around, the film, based on the novel by Tomoyoshi Murayama, even more depicts the ninja as backstage actors silently shuffling history into place. Thus Goemon takes advantage of a rift between the steady Mitsuhide (So Yamamura) and loose cannon Nobunaga (Tomisabur0 Wakayama) in an attempt to push him into rebellion. But what he may discover is that even with one tyrant gone, another will soon rise in its place. Hideyoshi (Eijiro Tono) seems to be forever lurking in the background, while Ieyasu makes a few experiences explaining that he intends to wait it out, allowing his rivals to destroy each other so he can swoop down and snatch the throne at minimal cost.

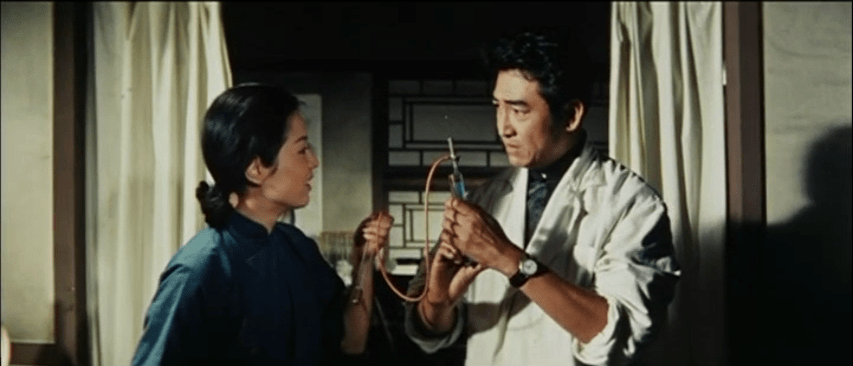

But he too has his ninja such as the legendary Hanzo Hattori (Saburo Date) who arrives to complicate the intrigue and tempt Goemon away from his attempts to live a normal life. Interestingly enough, one of the factors leading to Nobunaga’s downfall is his disregard for Buddhism in frequently burning temples associated with ninja along with everyone inside them. Burning with a desire for vengeance, Goemon describes Nobunaga as inhuman, a demon, though he also embodies the vagaries of the feudal era in which no one is really free. Nobunaga has built a large castle estate for himself while ordinary people continue to suffer under onerous demands from local lords. Hideyoshi has also done something similar in an attempt to bolster his status and prepare for his own inevitable bid for national hegemony.

The implication is that though the constant warfare of the Sengoku era is of course bad for farmers in particular, the political machinations which revolve around the egos of three men are far removed from the lives of ordinary people. Even so, the code of the ninja continues to be severe as we’re reminded that love and human happiness are not permitted to them. A female ninja spy working for Hanzo is despatched to Nobunaga’s castle to seduce his retainer Ranmaru but is cautioned that she must not allow her heart to be stirred. Predictably this seems to be a promise she couldn’t keep, eventually dying alongside him during an all out attack on the castle.

Goemon discovers something much the same in encountering further losses and personal tragedies, but takes on a somewhat crazed persona in his continuing pursuit of Nobunaga, grinning wildly amid the fires of his burning castle while taunting Nobunaga that he is the ghost of the Iga ninjas he has killed. Then again, he’s laid low by his own ninja tricks on discovering that Hideyoshi has had a special “nightingale floor” installed that lets out a song whenever someone crosses it, instantly ruining his attempt to infiltrate the castle. “The days when a few ninja could control the fate of the world are over,” Ieyasu ironically reflects though perhaps signalling the transition he embodies from the chaos of the Sengoku era to the oppress peace of the Tokugawa shogunate.

Somehow even bleaker than its predecessor, Yamamoto deepens the sense of nihilistic dread with increasing scenes of surreal violence and human cruelty from a baby been thrown on a fire to a dying commander teetering on his one leg and holding out just long enough to gesture at a sign requesting vengeance against those who have wronged him. Echoing the fate of the real Goemon, dubbed the Robin Hood of Japan for his tendency to steal from the rich to give to the poor, the conclusion is in its own way shocking but then again perhaps not for there can be no other in this incredibly duplicitous world of constant cruelty and petty violence.