Kikuko (Yoko Sugi) climbs the stairs to the roof of a department store and pauses at the top looking down on her friends below, but they appear to be looking down on her. They’re disappointed. She looks so “provincial”, even though she has no children and therefore more time to spend on herself. They’re envious of her “freedom” to return home late while they have to get back to their husbands or in-laws, but Kikuno isn’t really free at all while trapped in a stifling marriage to the incredibly dull and petulant Isaku (Ken Uehara).

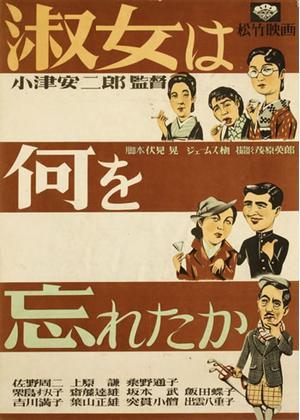

One of a series of films about marriage and originally envisaged as a sequel to Repast until Setsuko Hara fell ill, Husband and Wife (夫婦, Fufu) paints a rather bleak picture of married life even by Naruse’s standards. The couple are quite literally but also spiritually “homeless” in that they cannot find a home to share, while the absence of a domestic space to call their own prevents them from solidifying their marriage. They’re pushed out of Kikuko’s parents’ home because her brother’s getting married and they need the space, but Isaku drags his feet over finding somewhere else and leaves much of the legwork to Kikuko alone. The main problem seems to be that Isaku can’t afford anything decent, which places a strain on his male pride, but in a repeated motif, rather than confront the situation, he ignores it completely and then crassly presses his recently widowed colleague to let them rent a room in his now much emptier house.

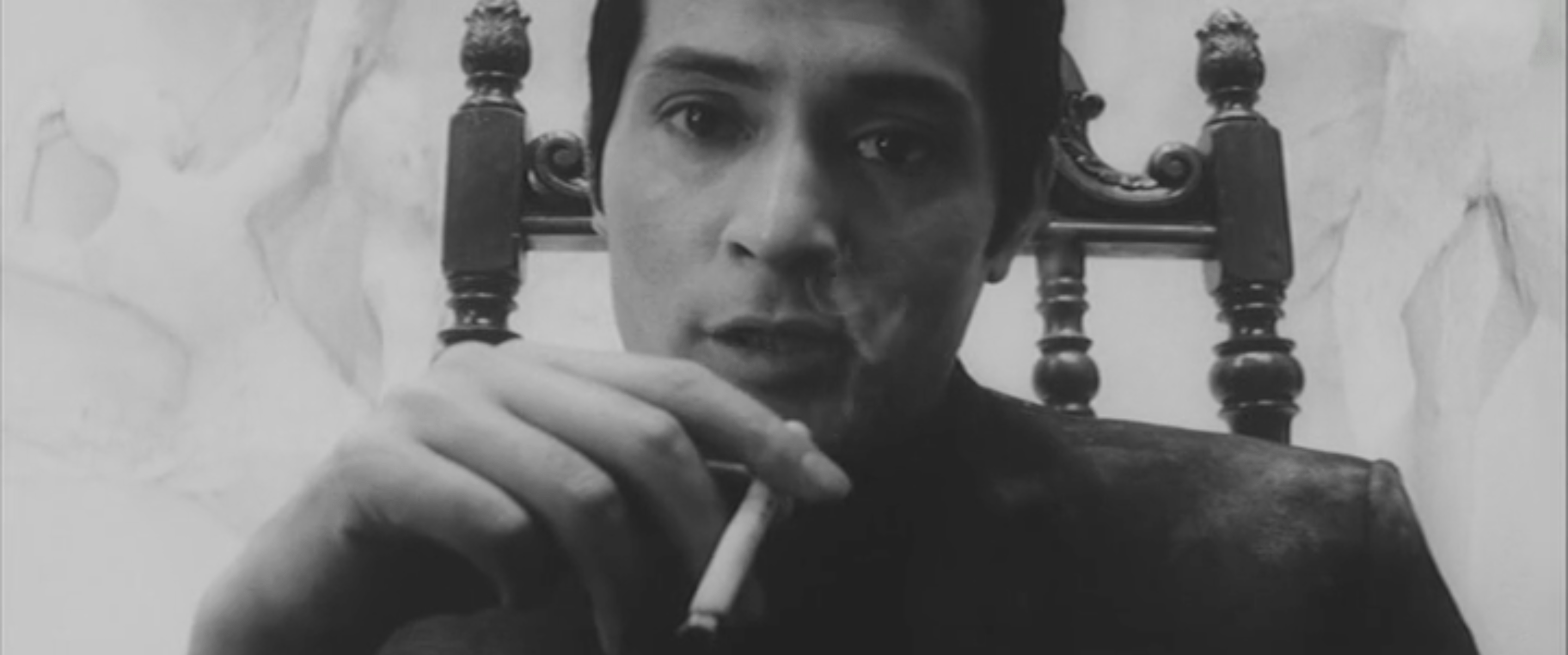

It’s a mystery why Isaku has so many financial problems when he and Takemura (Rentaro Mikuni) work for the same company, save that Isaku had evidently spent some time working in the provinces, and his colleague had already bought a home with no apparent money worries, but it further sets the two men apart and fuels Isaku’s sense of inadequacy. Having returned from a leave of absence following his wife’s death, Takemura is grief-stricken and apparently uxorious. He complains that he’ll never find another woman like his late wife, all while Isaku won’t shut up about the house and others relentlessly encourage him to remarry. Nevertheless, after the couple move in with him, a natural connection arises between Kikuko and Takemura who is Isaku’s total opposite, both in his treatment of Kikuko and general personality. Where Isaku is sullen and resentful, Takemura is cheerful despite his grief and generous of spirit. Kikuko effectively becomes a wife to both men, taking care of each of them by cooking and cleaning, but while Takemura goes out of his way to thank her, all Isaku does is run her down and humiliate her in front of company.

Then again, having fallen in love with Kikuko precisely because she is a “proper wife,” Takemura then runs his own late wife down by complaining that she wasn’t very pretty and couldn’t cook. The only thing she had going for her was her health, and then she died. He says got a bum deal, and that Kikuko has shown him a different side of womanhood. When two colleagues come to the house and compliment Kikuko’s cooking but are surprised when she eats nothing herself (because they have no money), Isaku responds to their assertion that it’s difficult to be a housewife by replying that men work hard all day while women “only” have to look after the house. For her part, Kikuko says that she was happier when she was working. Men can fall in love several times, but once a woman’s married her romantic life is over. As her friend tells her, men soon get bored of their wives and hers has already taken a mistress at work.

At several points and with the women in earshot, the men warn each other about the pitfalls of marriage. Irritated that Kikuko has returned to their home on New Year’s Eve after becoming fed up with Isaku, her father advises her brother that women show their true faces after six or seven years and it’s going to horrify him. Isaku tells him not to be too nice or obedient during the early days because his wife will get used to it, while Kikuko counters that men are overgrown children and as long as you make sure to cradle them like babies everything will be fine. Neither of them seem to have a very positive idea of what marriage should be and frame it almost in terms of a war in which they are continually at odds with each other. Isaku describes a husband and wife as a pair of scissors, intending it as a positive metaphor about how one half can’t cut alone, before reframing it as two knives coming together. He becomes unpleasant and chauvinistic, blaming Kikuko for everything by complaining that it’s her fault that he wears a torn up old coat that causes him some embarrassment in front of his boss and a tactless geisha, while criticising her for not having the bath ready when he comes home tired from working all day. Kikuko points out that men seem to assume they’re the only ones who get tired while her loved up brother swears he’ll be different and even if they’re in the honeymoon phase, they do seem much happier and more suited than the already resentful Kikuko and Isaku.

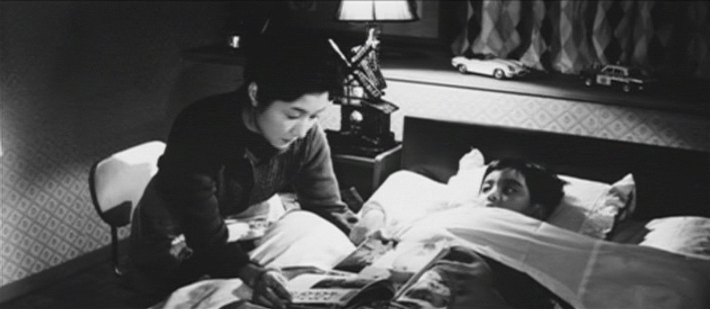

It’s the sister-in-law who throws them a lifeline by introducing them to a relative looking to rent a vacant room, allowing them a means to save their marriage by leaving Takemura’s house. Increasingly resentful of the growing attachment between Kikuko and Takemura, Isaku starts avoiding coming home and hanging out with a young woman at the office with, at least, the danger of a burgeoning affair for which he’s taken to task by Takemura. As Takemura says, it’s not much of a marriage if Isaku can’t trust his wife while Kikuko is eventually so sick of the cold shoulder and constant denigration that she considers leaving him. The new apartment finally gives them a domestic space they can call their own, but it comes with the caveat. The landlady doesn’t allow children because the tenant next door is an ikebana teacher who demands peace and quiet, but Kikuko is in fact already pregnant which might present another means of saving their marriage by becoming a family but Isaku immediately rejects it. He complains he doesn’t have any more money to move again and tells Kikuko to get an abortion, strong-arming her when she refuses. Kikuko can’t go through with it and the nicest thing Isaku says to her in the entire picture is that they can go home, he’s giving in and will raise the child even if it’s difficult. But even this bittersweet moment seems more like condemning them to marriage rather than repairing their relationship with Isaku only grudgingly accepting, most likely because he realises that his marriage is dead anyway if he forces Kikuko to give up their child against her wishes. Despite the changing season, the air between them remains frosty, and marriage is exposed for the prison that it is trapping each of them in loneliness and resentment rather than bringing them together in joy as they prepare to become a family rather than just husband and wife.

Husband and Wife screened at Japan Society New York as part of Mikio Naruse: The World Betrays Us – Part I.