The Olympics may have been postponed and everything seems like it’s on pause, but the BFI’s planned mammoth Japan season is still doing all it can to make its way to us in the 2020 that never was. With the cinemas closed for the foreseeable future, the BFI will be making the first part of the season available online via BFI player with strands dedicated to golden age directors Akira Kurosawa and Yasujiro Ozu as well as a series of classics including films by Mikio Naruse and Seijun Suzuki, cult movies, and the best in 21st century cinema. Once the BFI reopens, we can also look forward to some rarer treats from this century and the last.

BFI Player

A series of strands will begin streaming via BFI Player over a six month period beginning with Akira Kurosawa and Classics (11th May), followed by Yasujiro Ozu (5th June), Cult (3rd July), Anime (31st July), Independence (21st August), 21st Century (18th September), and J-Horror (30th October). Subscriptions to BFI Player are available for £4.99 p/m following a two week free trial.

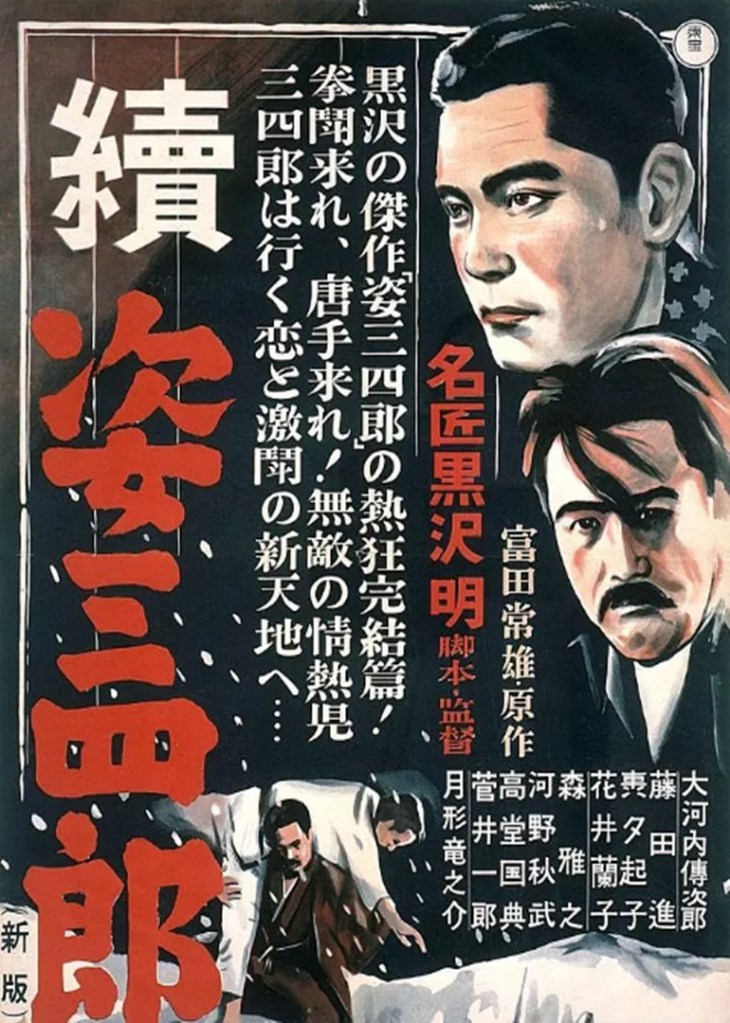

Akira Kurosawa (11th May)

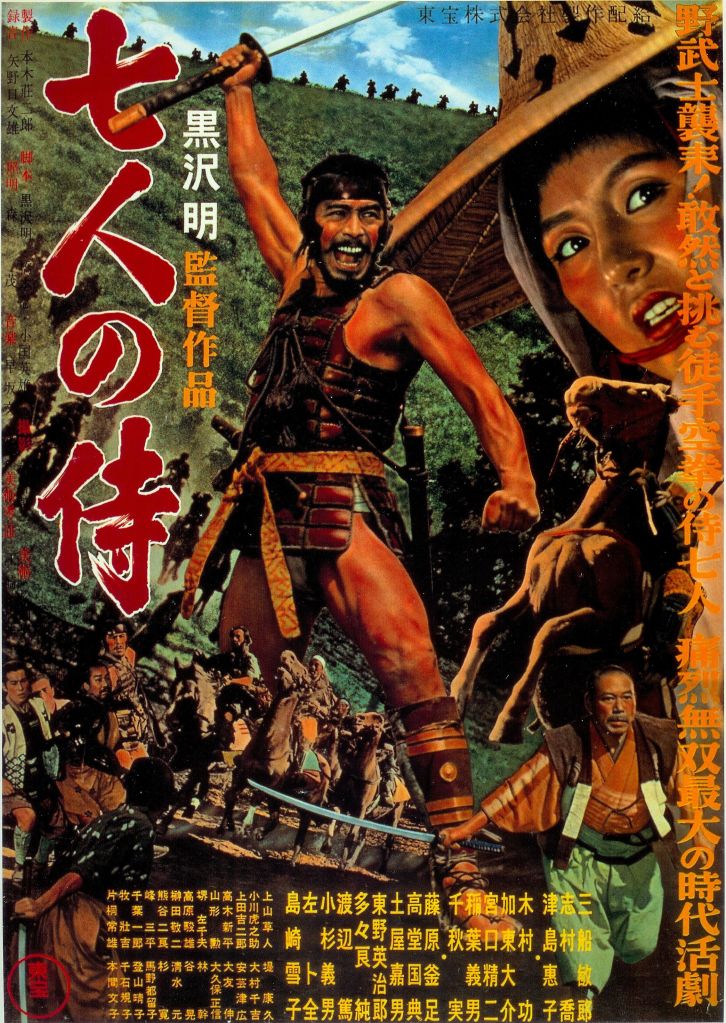

- Seven Samurai – classic jidaigeki gets a post-war twist as a collection of down on their luck samurai come to the rescue of peasants beset by bandits.

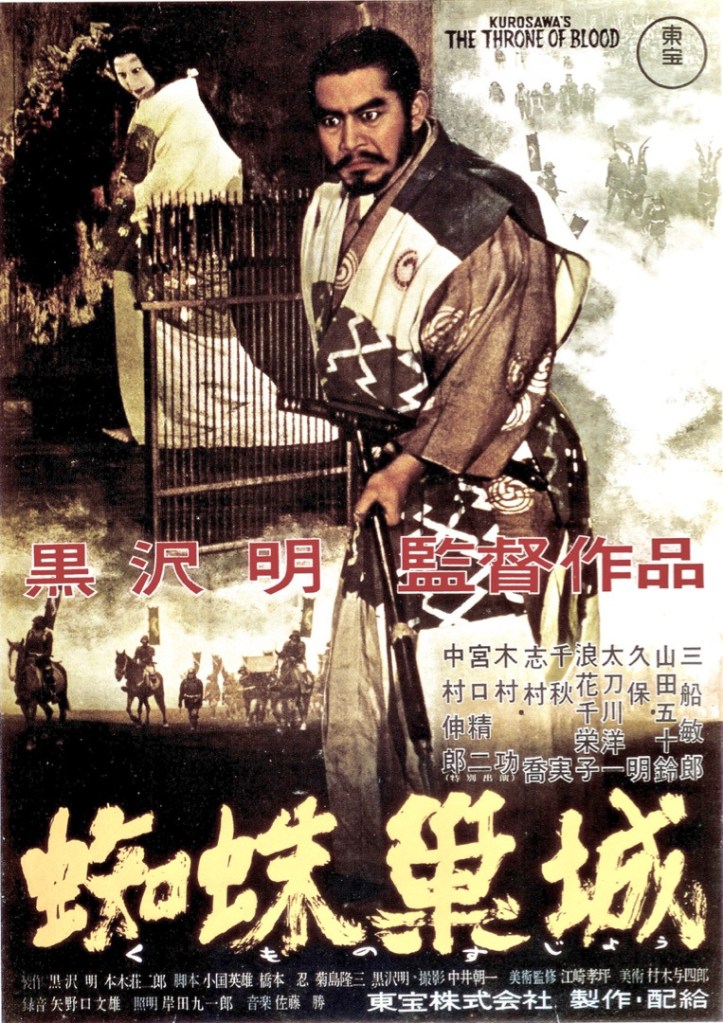

- Throne of Blood – eerie retelling of Macbeth starring Toshiro Mifune as the man who would be king and Isuzu Yamada as his ambitious wife.

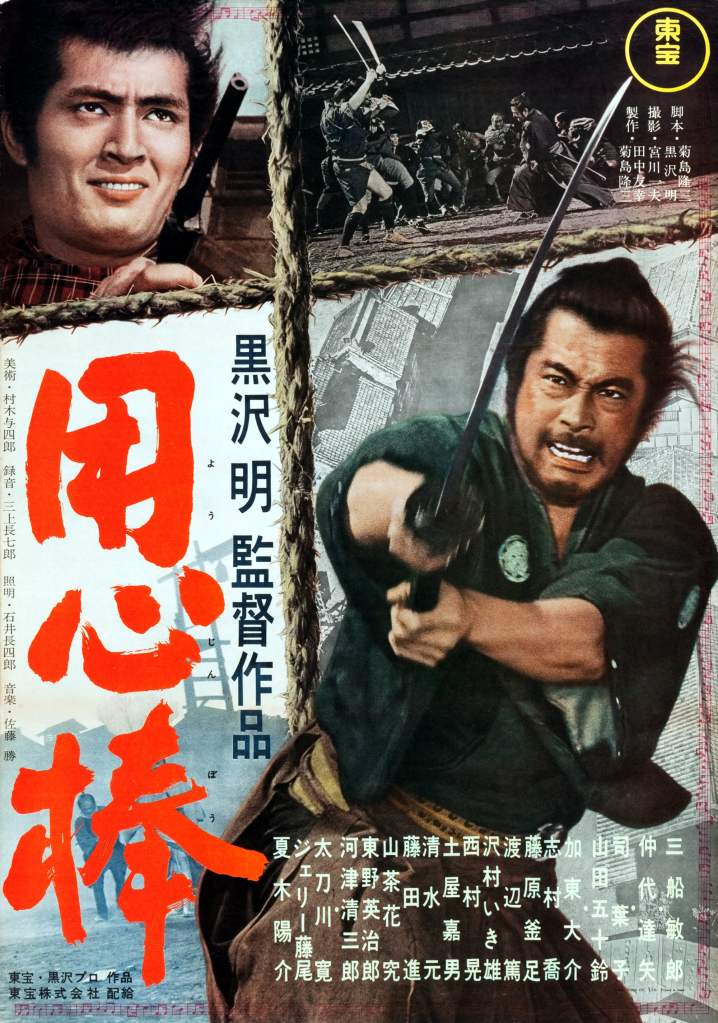

- Yojimbo – samurai western starring Toshiro Mifune as a ronin drifter wandering into a turf war.

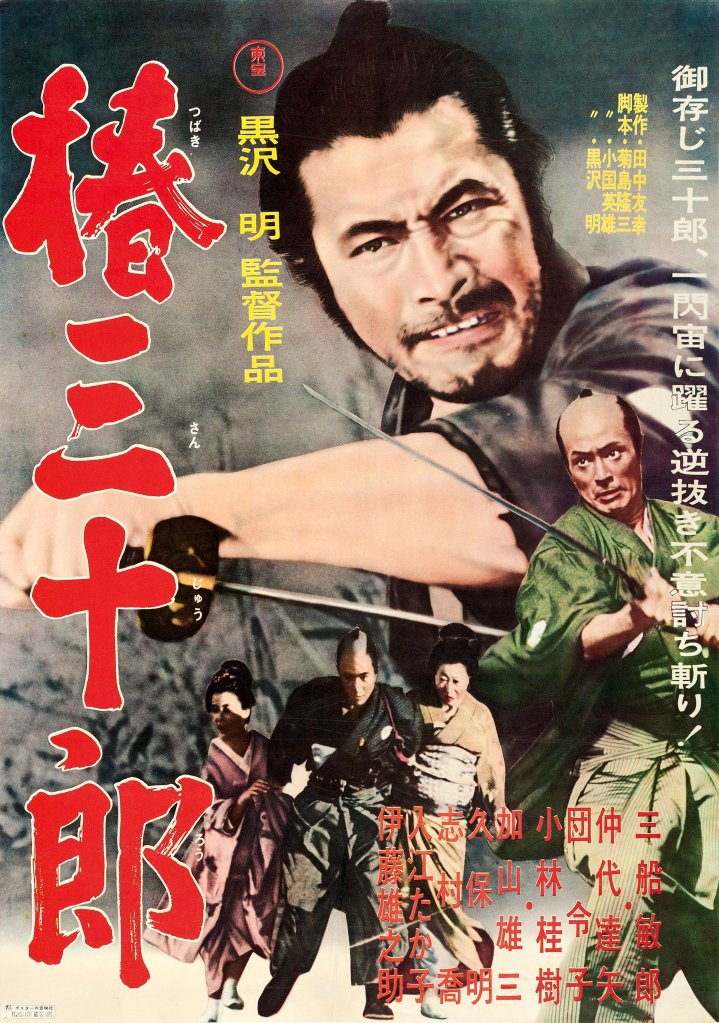

- Sanjuro – sequel to Yojimbo in which Mifune reprises his role as the titular Sanjuro as he helps some locals stand up to samurai corruption.

- Rashomon – a series of witnesses provides contradictory accounts of the same event in an adaptation of the story by Ryunosuke Akutagawa starring Toshiro Mifune, Machiko Kyo, and Masayuki Mori.

- The Men Who Tread on the Tiger’s Tail – comedic kabuki adaptation in which a samurai attempts to escape with his retinue after being betrayed by his brother by disguising himself as a monk.

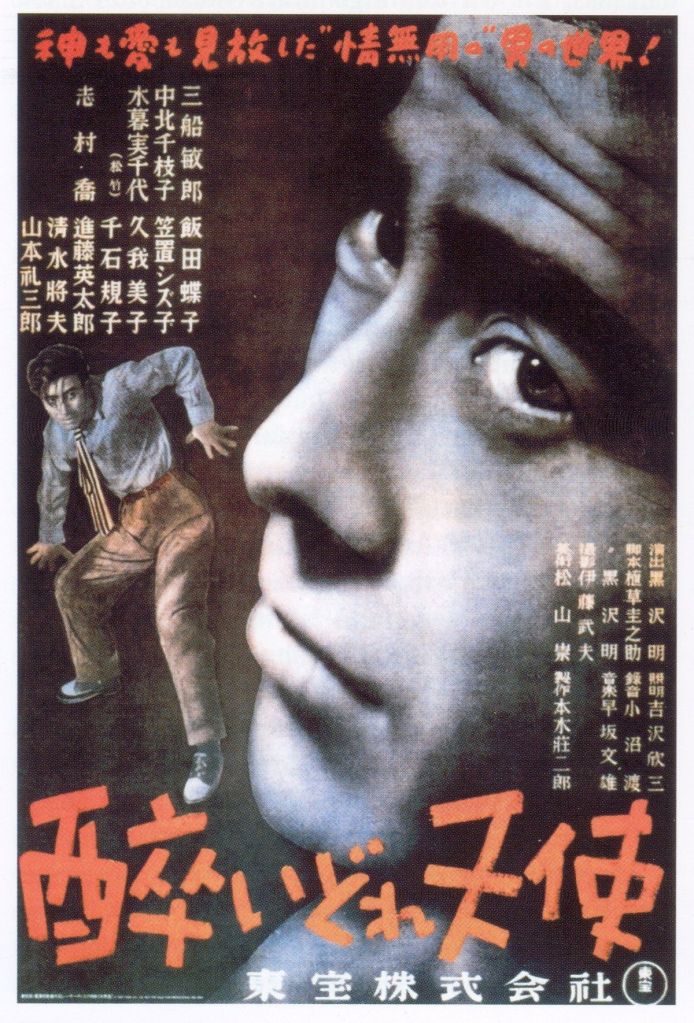

- Drunken Angel – post-war tragedy starring Toshiro Mifune at his most dashing as gangster dying of TB and Takashi Shimura as the compassionate yet alcoholic doctor trying to save him.

- Stray Dog – a policeman (Mifune) and his partner (Shimura) scour post-war Tokyo for a missing gun.

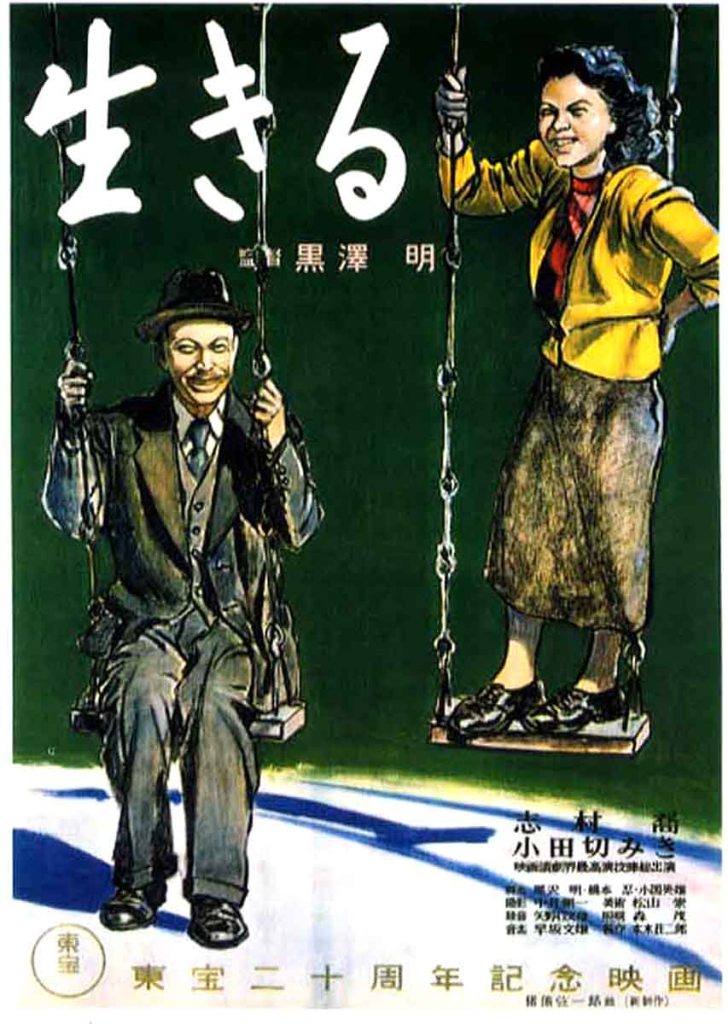

- Ikiru – existential drama starring Takashi Shimura as a civil servant reflecting on his life after discovering he has a terminal illness.

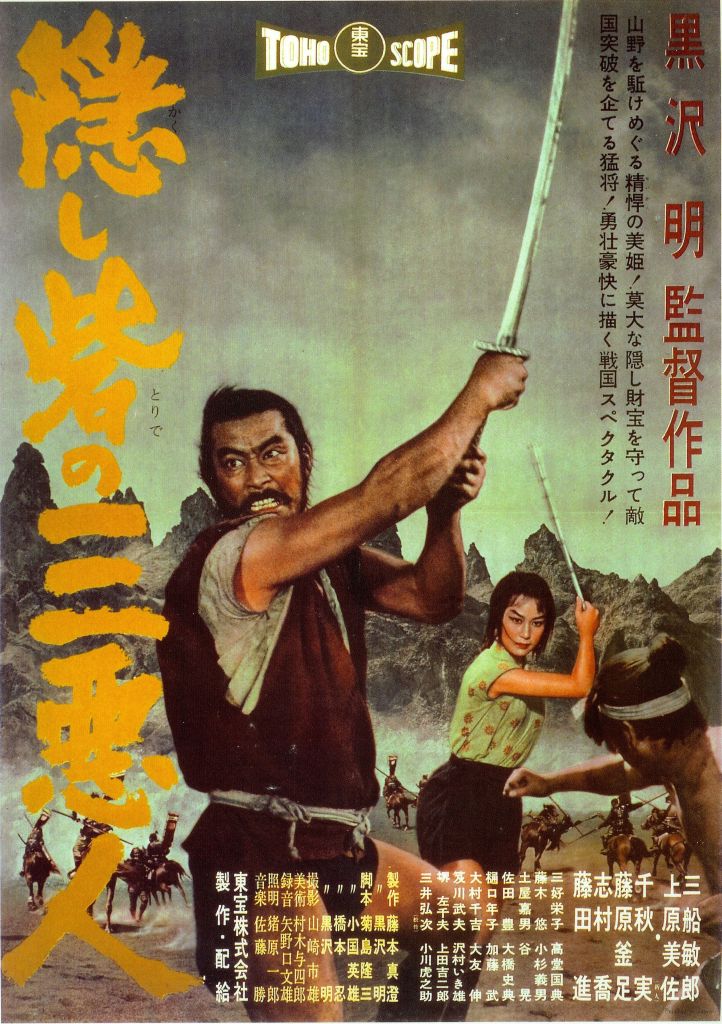

- Hidden Fortress – two bumbling peasants agree to escort a general and a princess in disguise to safe territory in return for gold.

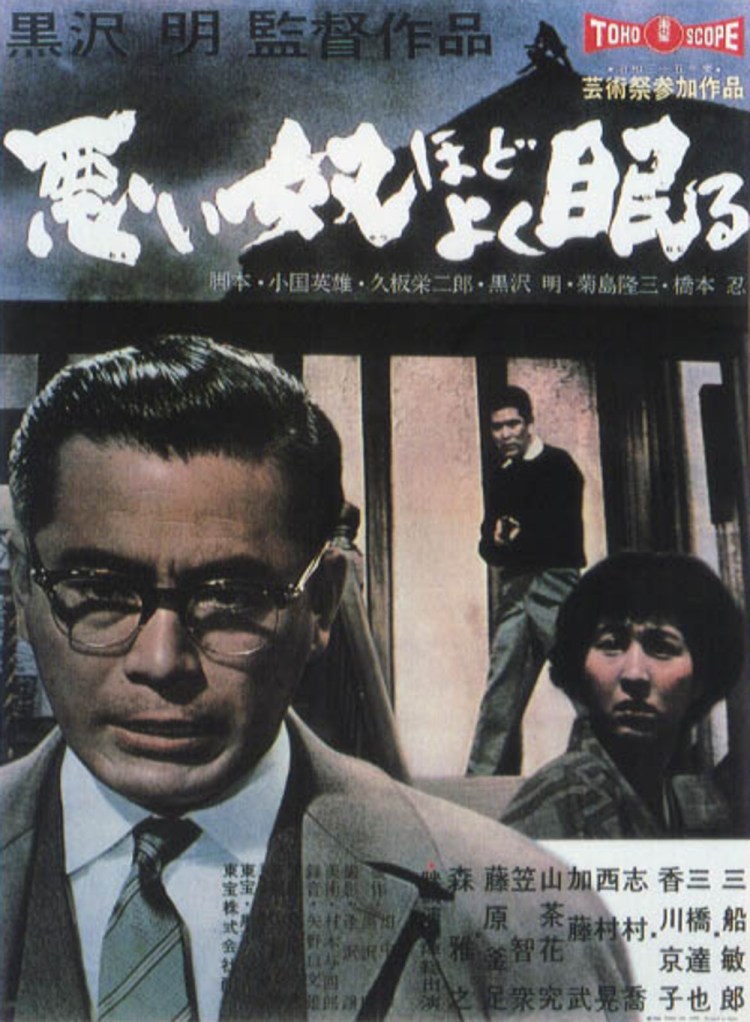

- The Bad Sleep Well – contemporary take on Hamlet starring Toshiro Mifune as man enacting an elaborate revenge plot against the corrupt CEO who drove his father to suicide. Review.

- Red Beard – humanistic drama starring Toshiro Mifune as a gruff yet compassionate doctor to the poor. Review.

- Ran – King Lear relocated to feudal Japan.

- Sanshiro Sugata Pt 1 & 2 – drama inspired by the life story of a legendary judo master.

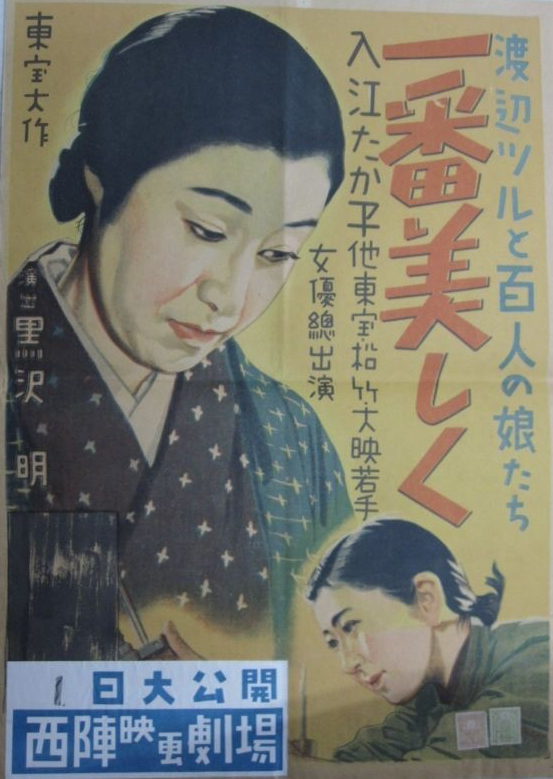

- The Most Beautiful – naturalistic national policy film from 1944 following the lives of female factory workers.

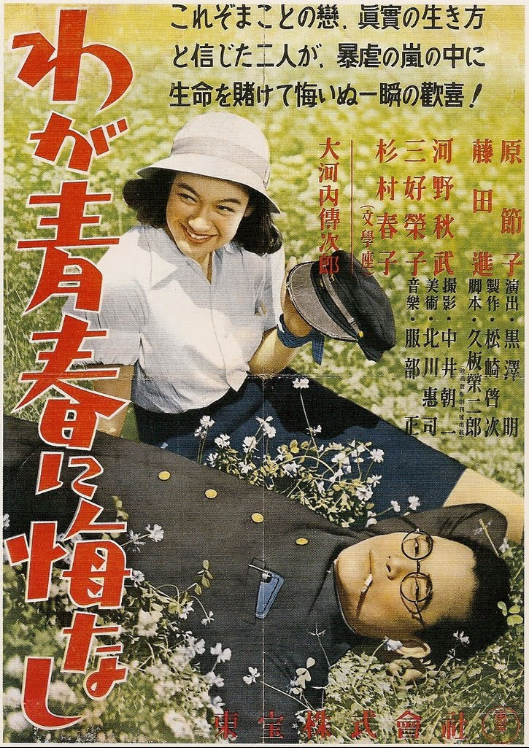

- No Regrets for Our Youth – 1946 drama starring Setsuko Hara as a professor’s daughter who marries a radical leftist later executed as a spy.

- One Wonderful Sunday – post-war drama in which an engaged couple attempt to have a nice day out in Tokyo for only 35 yen.

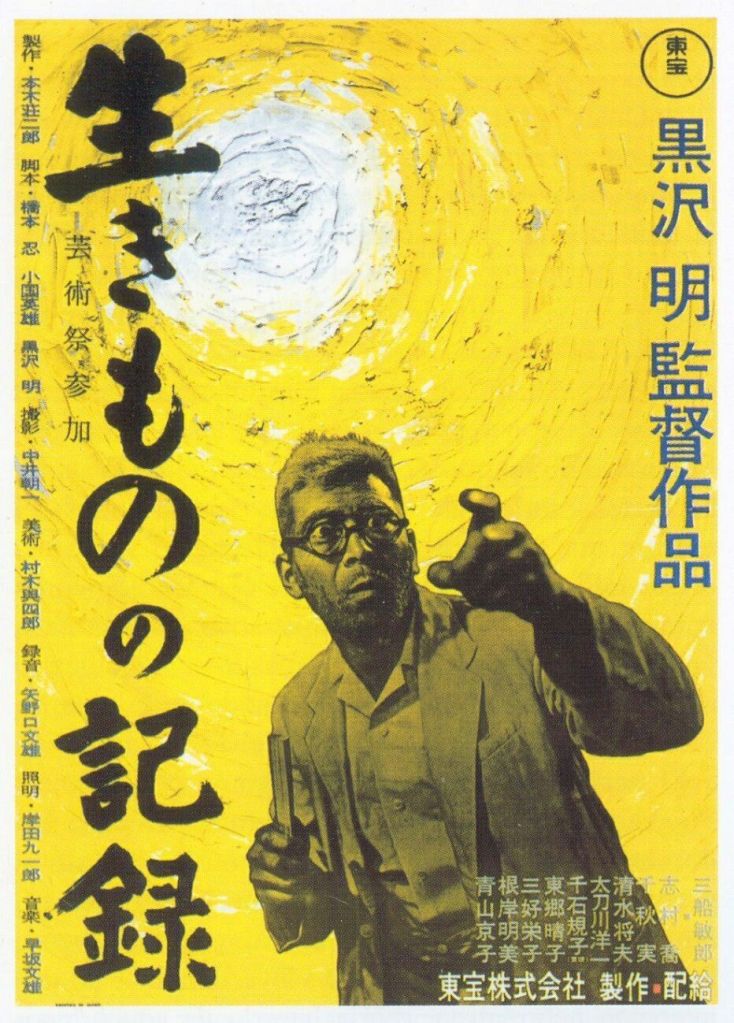

- I Live in Fear – Toshiro Mifune stars as a factory owner so terrified of nuclear attack that he becomes determined to move his family to the comparative safety of Brazil while they attempt to have him declared legally incompetent on account of his intense paranoia.

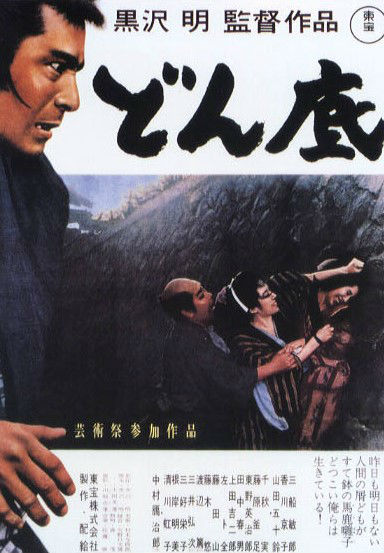

- The Lower Depths – 1957 adaptation of Gorky’s novel following the lives of a collection of people living in an Edo-era tenement.

- High and Low – Toshiro Mifune stars as a wealthy man encountering a dilemma when his chauffeur’s son is kidnapped after being mistaken for his own.

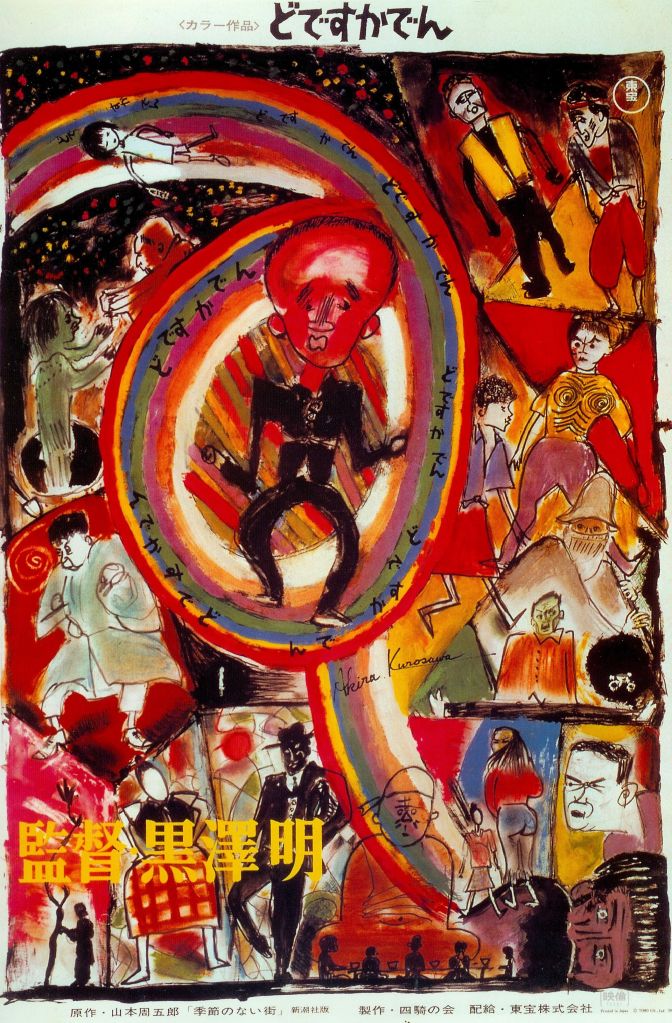

- Dodes’ka-den – Kurosawa’s first colour film exploring the lives of a collection of people living in a shantytown above a rubbish dump.

Classics (11th May)

- Late Chrysanthemums – Naruse’s 1954 drama following the lives of four former geishas (played by Haruko Sugimura, Chikako Hosokawa, Yuko Mochizuki, and Sadako Sawamura) as they try to get by in the complicated post-war economy.

- Floating Clouds – Naruse’s 1955 romantic drama starring Hideko Takamine and Masayuki Mori as former lovers floundering in the post-war landscape. Review.

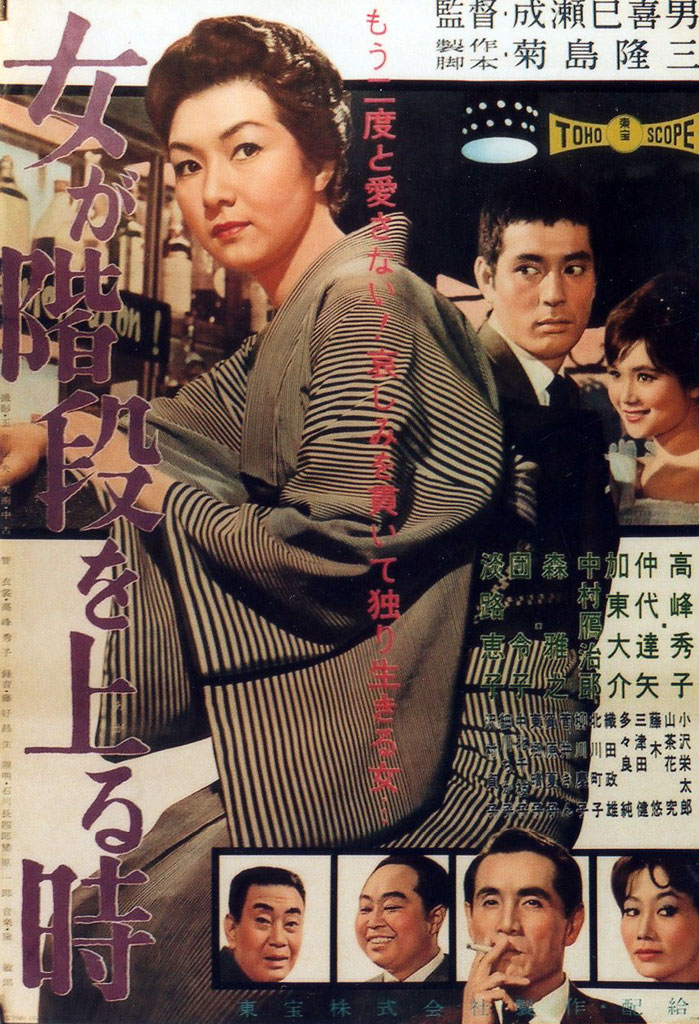

- When a Woman Ascends the Stairs – Naruse’s 1960 drama starring Hideko Takamine as a widow turned Ginza bar hostess.

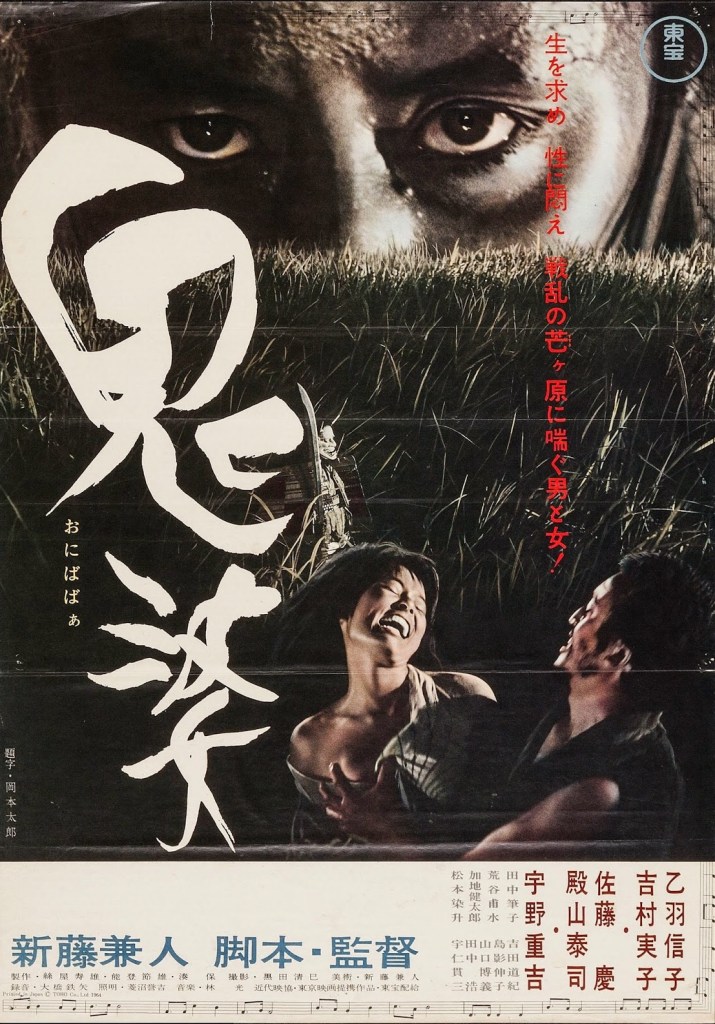

- Onibaba – period horror from Kaneto Shindo in which a mother and her daughter-in-law survive by murdering samurai and selling their armour. Review.

- Kwaidan – horror anthology from Masaki Kobayashi featuring adaptations of classic Japanese folktales.

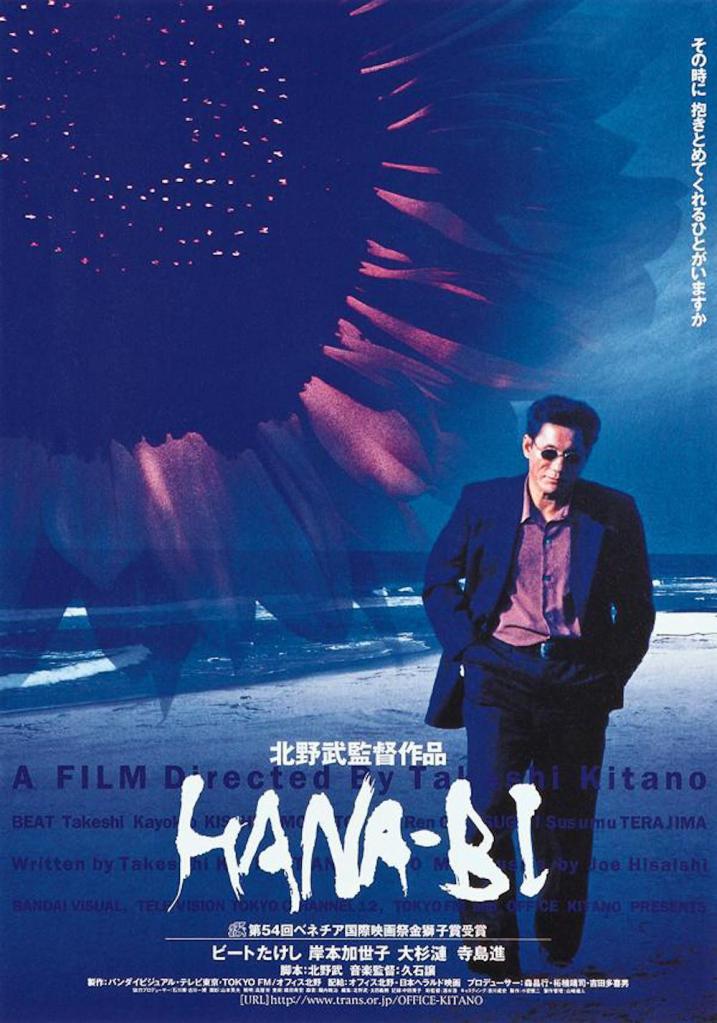

- Hana-Bi – noirish poetry from Takeshi Kitano as a former policeman takes on an unwise loan from yakuza to care for his terminally ill wife. Review.

- Black Rain – Shohei Imamura’s 1989 drama set in the aftermath of the atomic bomb attack on Hiroshima.

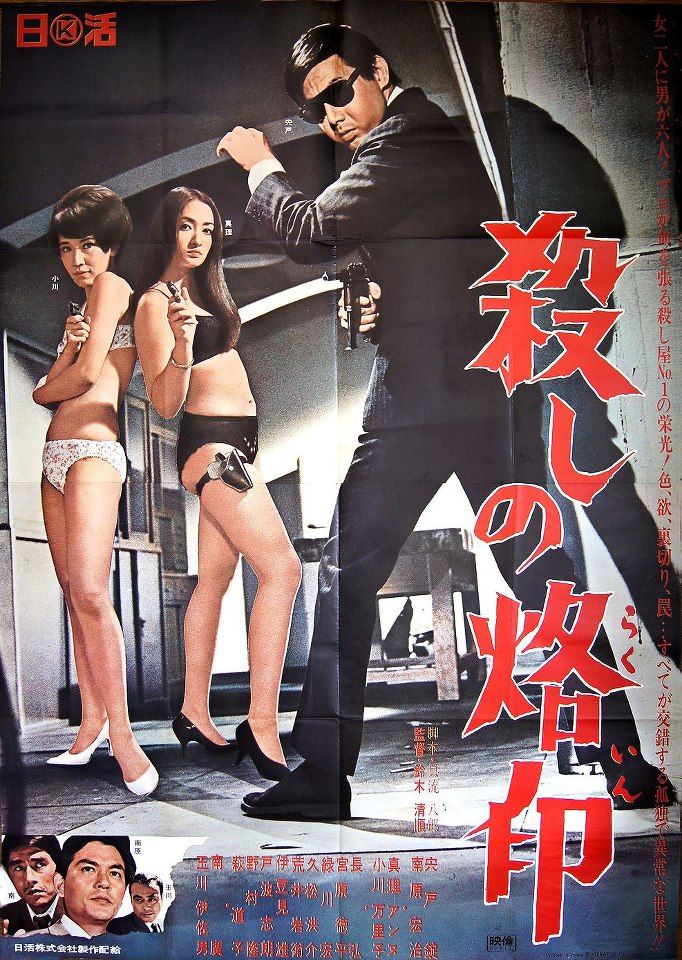

- Branded to Kill – the anarchic 1967 hitman drama that got Seijun Suzuki fired from Nikkatsu.

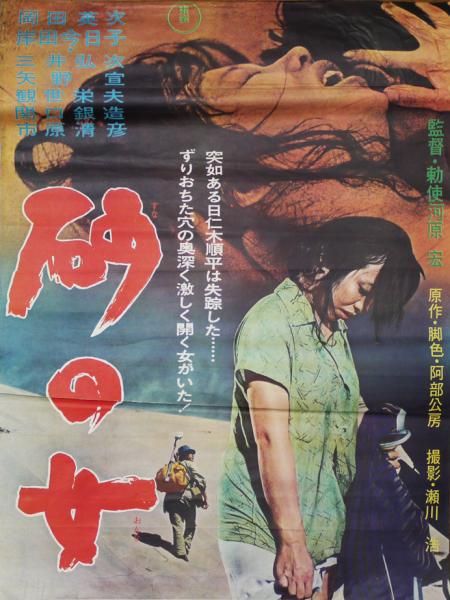

- Woman of the Dunes – Hiroshi Teshigahara’s adaption of the Kobo Abe novel in which a bug collector is imprisoned in a sand dune after missing the last bus home and being persuaded to spend the night in the home of a local woman.

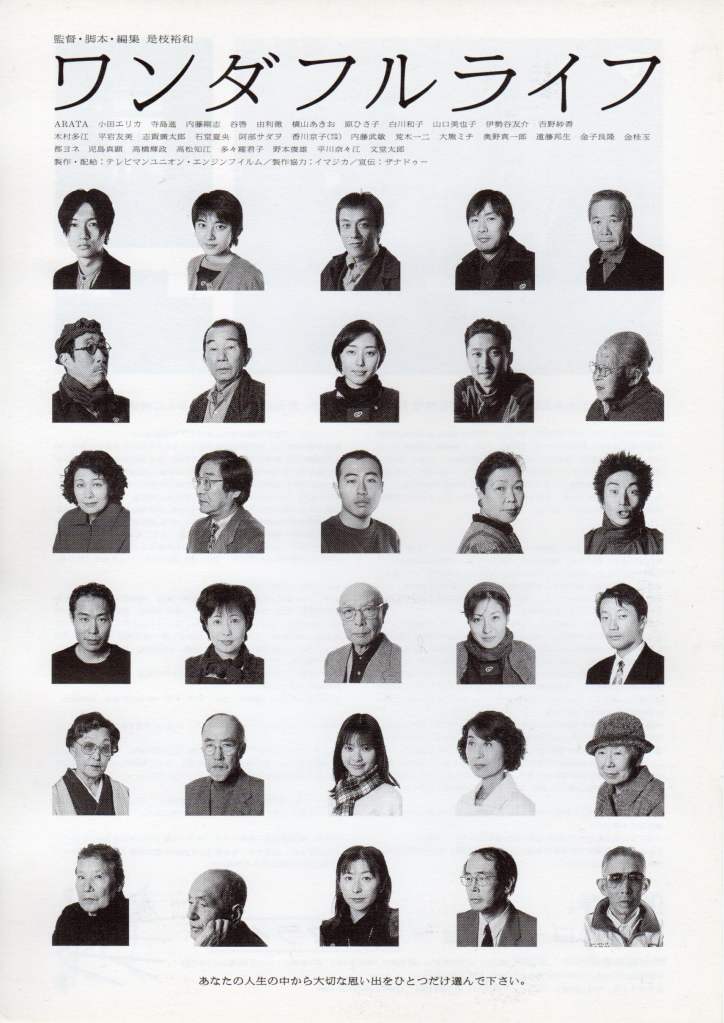

- After Life – poignant drama from Hirokazu Koreeda in which the recently deceased are permitted to recreate a favourite memory. Review.

- Youth of the Beast – Seijun Suzuki drama starring Jo Shishido as a mysterious figure playing double agent to engineer a gang war. Review.

- Gate of Hell – period drama starring Machiko Kyo as a loyal wife who tricks a man trying to kill her husband to have her for himself to kill her instead. Review.

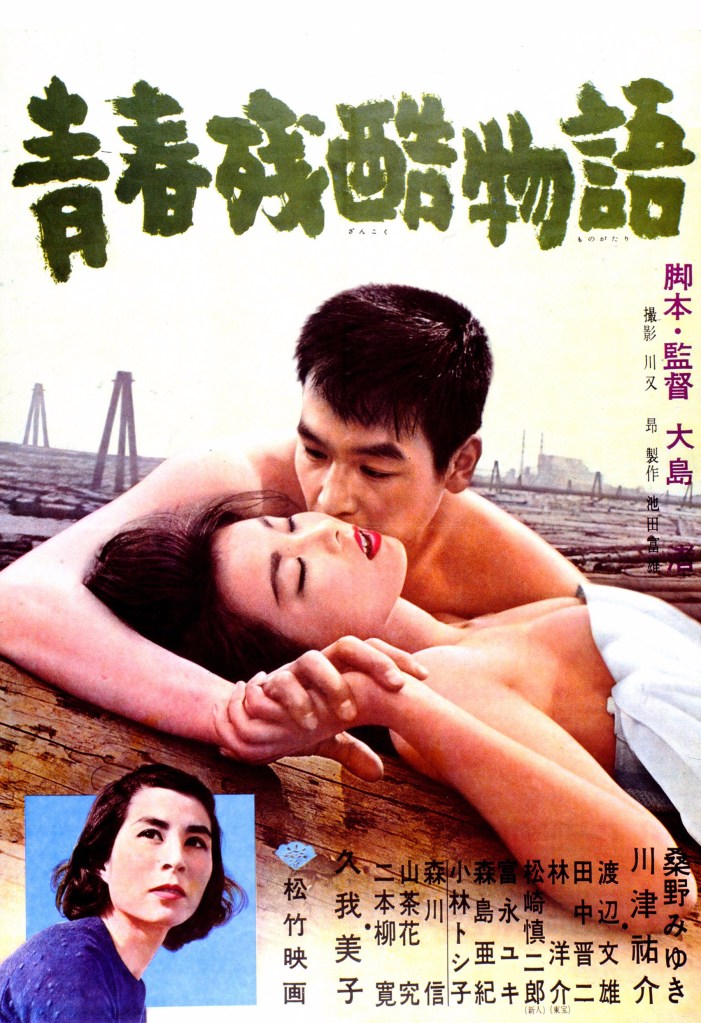

- Cruel Story of Youth – post-Sun Tribe youth drama from Shochiku directed by Nagisa Oshima. Review.

- An Actor’s Revenge – Kon Ichikawa’s visually stunning tale of vengeance and madness. Review.

Yasujiro Ozu (5th June)

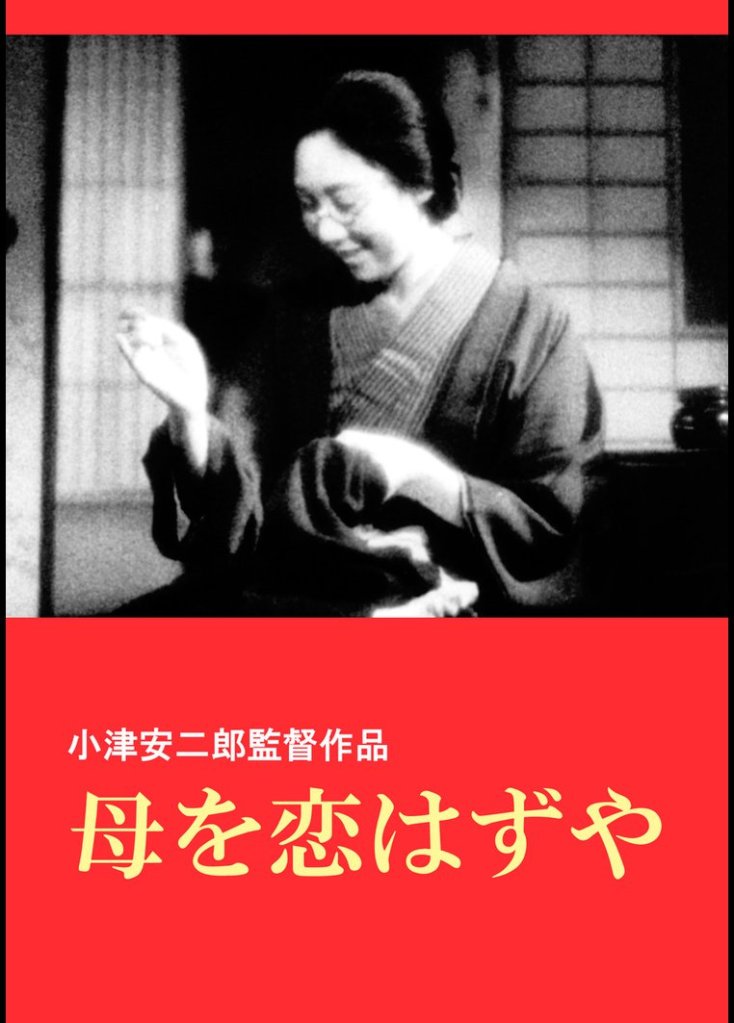

- I Was Born, But… – 1932 silent in which two little boys have a hard time accepting that their dad has an inauthentic work persona. Review.

- Flavour of Green Tea Over Rice – 1952 drama starring Shin Saburi and Michiyo Kogure as an unhappily married couple. Review.

- Tokyo Story – post-war classic in which an old couple from the country make a rare trip to the city to see their grown up children but are disappointed to discover that they don’t have much time for them.

- Good Morning – consumerist comedy in which two little boys go on a pleasantries strike to get their parents to buy them a TV.

- Late Autumn – drama in which a young widow tries to marry off her daughter with the help of old friends from college. Review.

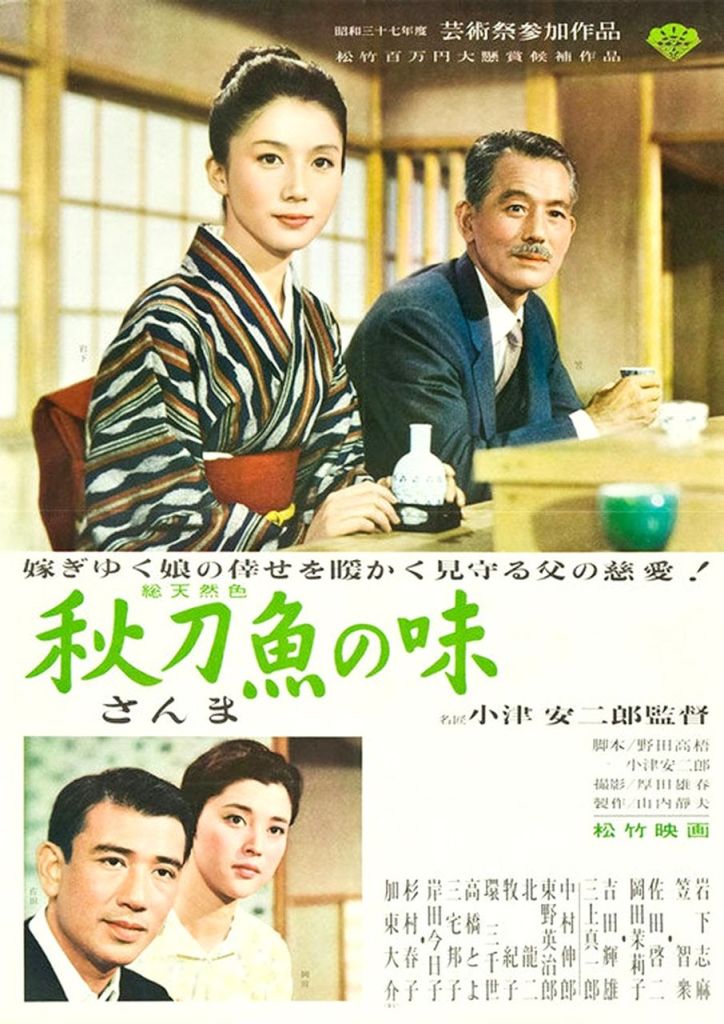

- An Autumn Afternoon – Ozu’s final film stars Chishu Ryu as an ageing widower preparing to marry off his only daughter. Review.

- Early Summer – a family’s attempt to marry off a daughter is frustrated when they realise she is carrying a torch for the widower next door.

- Equinox Flower – drama of generational conflict in which an authoritarian father is forced to accept his daughter’s right to choose her own husband without asking for his advice or consent.

- Late Spring – classic in which a young woman’s close relationship with her widowed father leaves her reluctant to marry.

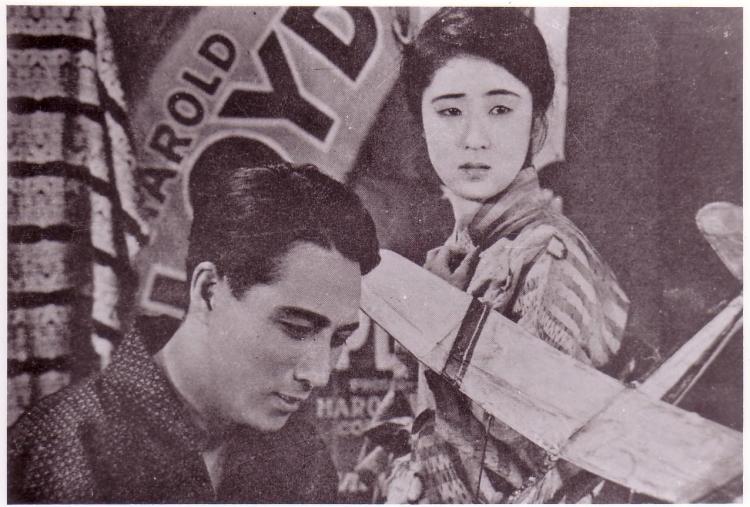

- Dragnet Girl – silent crime film starring Kinuyo Tanaka as a gangster’s moll who decides to reform after meeting the sister of a new gang member.

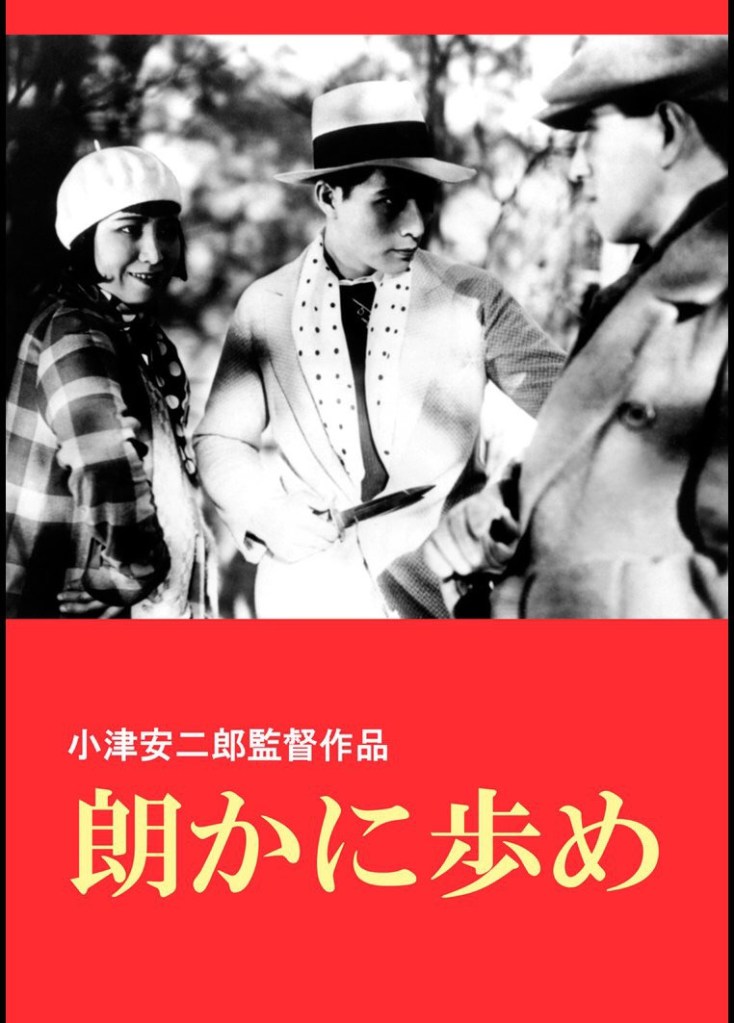

- Walk Cheerfully – silent crime film in which a gangster wants to go straight after falling for an ordinary girl.

- I Flunked, But… – silent college comedy.

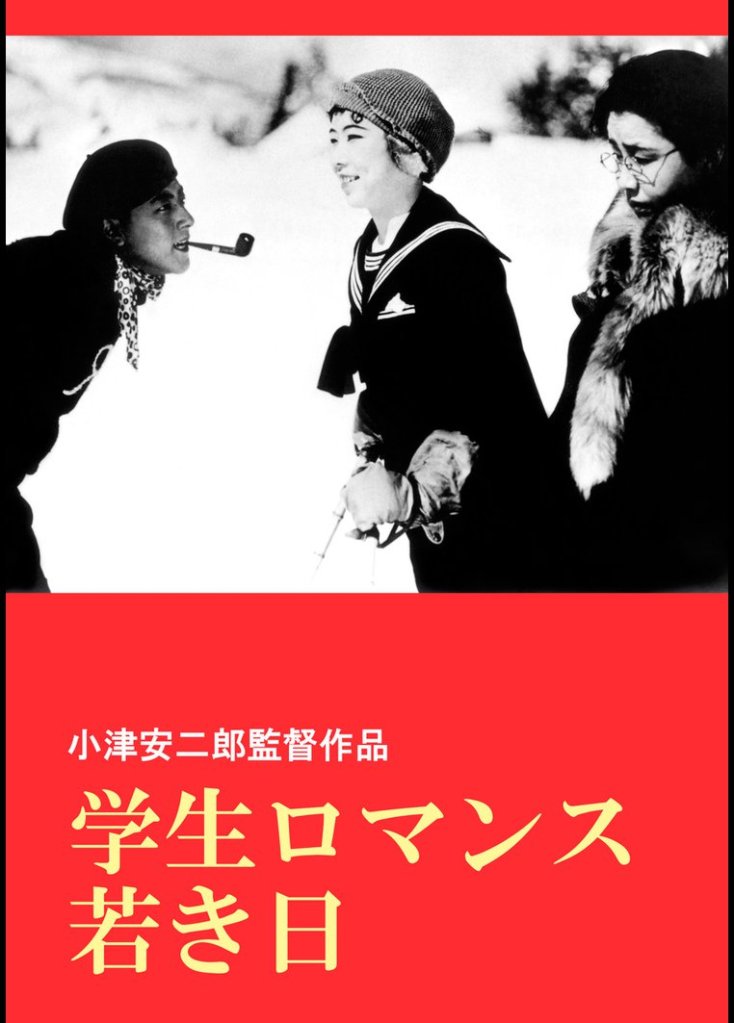

- Days of Youth – two students compete for the affections of the same girl.

- Where Now Are the Dreams of Youth? – tragedy enters a carefree college existence when a naive young man games the system to offer all his friends jobs after inheriting his father’s company.

- Woman of Tokyo – silent drama in which a student is devastated to learn that his older sister is not a translator as he thought but works as a bar hostess to finance his education.

- Early Spring – rare Ozu drama exploring the taboo of an extra-marital affair.

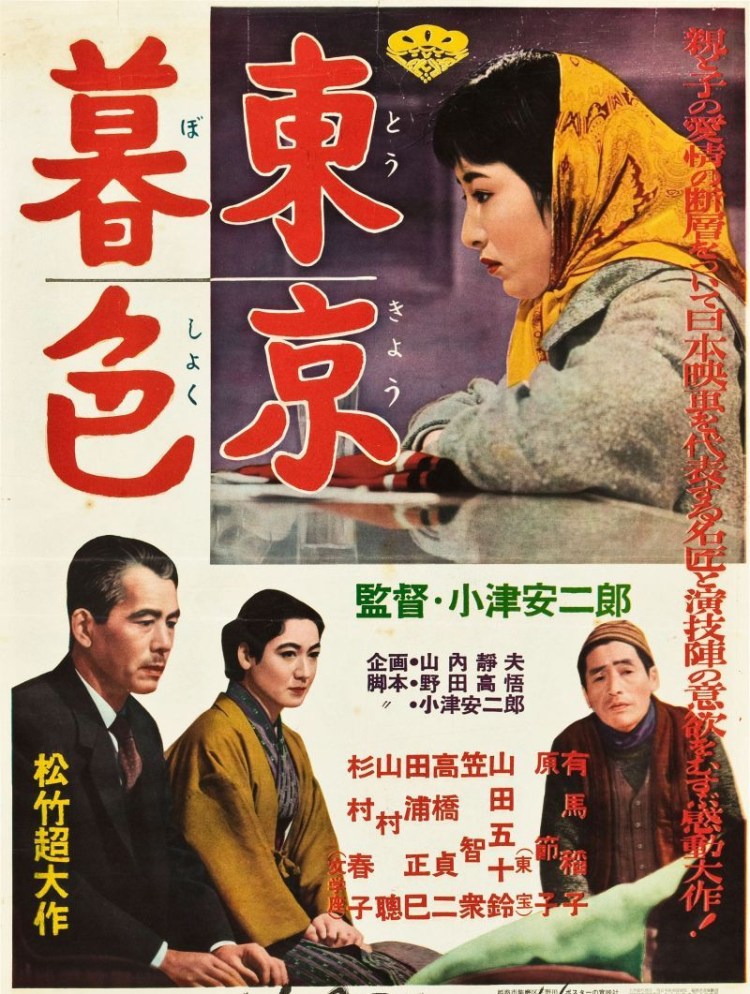

- Tokyo Twilight – grown up sisters reunite with the mother who abandoned them as children to run off with another man.

- That Night’s Wife – 1930 crime drama in which a man is hunted by police after resorting to robbery to pay for his daughter’s medication.

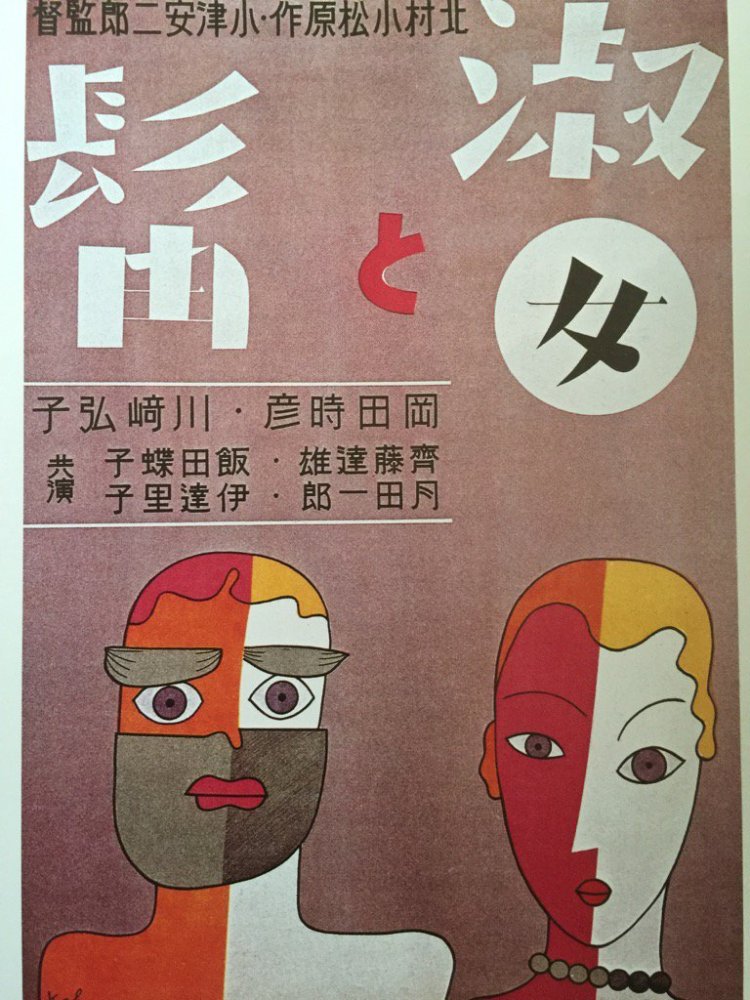

- The Lady and the Beard – 1931 comedy in which a traditionally minded man’s refusal to shave off his beard makes it difficult to move on with his life.

- A Mother Should Be Loved – a young man discovers the woman who raised him is not his birth mother.

- The Only Son – drama in which a mother visits her grown-up son and is disappointed to learn he has a wife and child he never told her about.

- What Did the Lady Forget? – a modern girl visits her professor uncle but is disturbed to see him henpecked by his traditionalist wife.

- Brothers and Sisters of the Toda Family – a widow discovers that her grown up children are unwilling to support her and their younger sister when their father suddenly dies leaving them deep in debt.

- There Was a Father – a father’s attempts to do the best for his son perpetually keep them apart.

- A Hen in the Wind – a returned soldier struggles to accept his wife’s decision to resort to prostitution to pay for a doctor to save their son’s life in Ozu’s atypically dark post-war drama.

Cult (3rd July)

- Gushing Prayer – pink film from Masao Adachi dramatising despair in the wake of the failure of the student movement.

- Inflatable Sex Doll of the Wastelands – pink film in which a hitman is brought into contact with the yakuza who killed his girlfriend while looking for kidnapped woman.

- Stray Cat Rock: Delinquent Girl Boss – first in the Stray Cat Rock series starring Akiko Wada and Meiko Kaji.

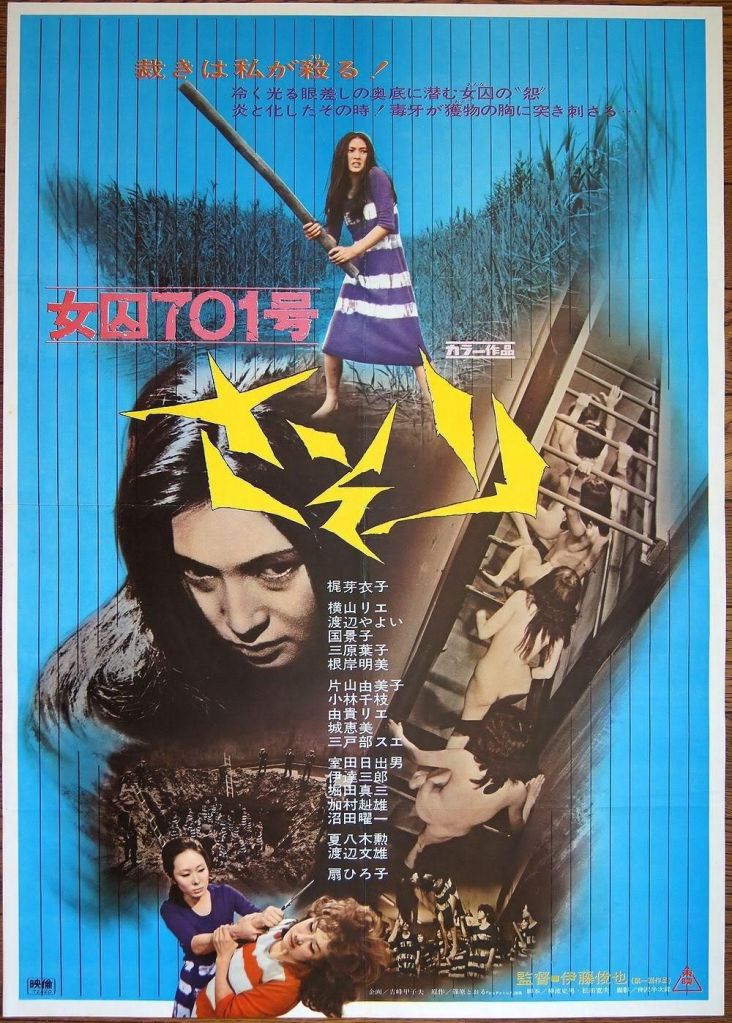

- Female Prisoner #701: Scorpion – Meiko Kaji stars as a woman falsely imprisoned.

- Lady Snowblood – Meiko Kaji stars as a young woman seeking revenge against the men who raped her mother.

- Orgies of Edo – three tales of Genroku decadence from Teruo Ishii. Review.

- House – surreal horror from Nobuhiko Obayashi in which a high school girl takes some friends to visit her aunt but ends up in a colourful nightmare world.

Anime (31st July)

- Summer Wars – Mamoru Hosoda’s breakthrough feature follows the summer adventures of maths genius and moderator of online world Oz Kenji Koiso as he is unexpectedly invited on a trip with his crush, Natsuki, only to be expected to play the part of her fake fiancé whilst also dealing with a vast internet-based conspiracy.

- The Girl Who Leapt Through Time – Mamoru Hosoda’s loose sequel to the much-loved novel by Yasutaka Tsutsui.

- Wolf Children – touching animation from Mamoru Hosoda in which a single-mother raising two children alone must comes to terms with the different paths her children take.

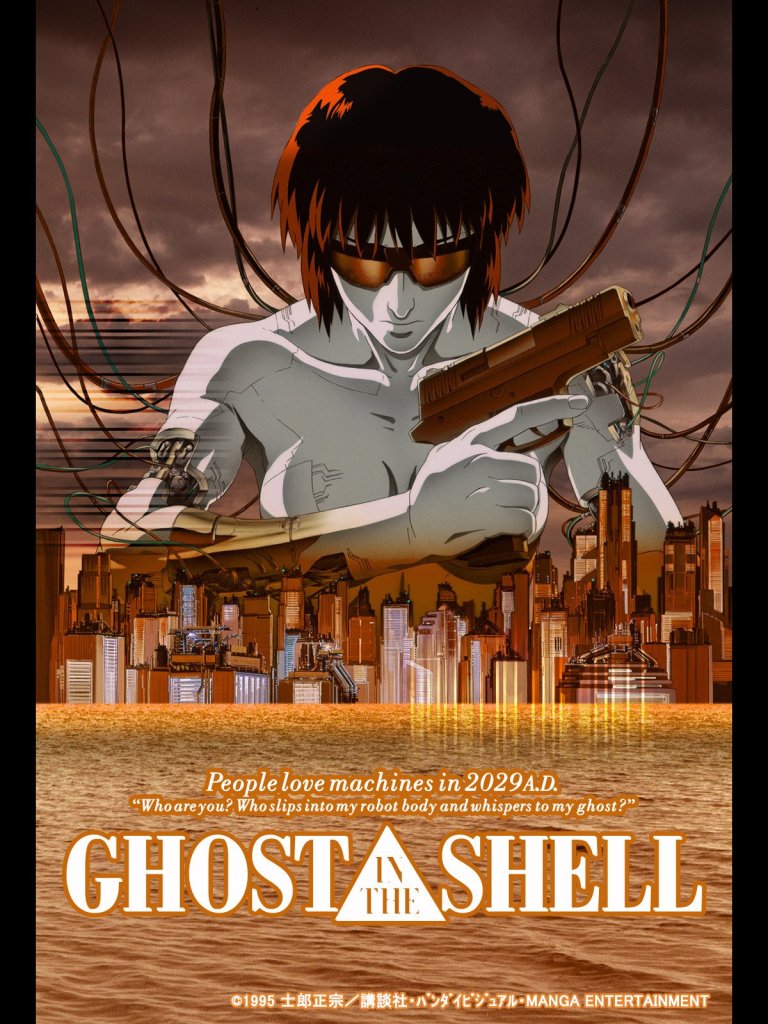

- Ghost in the Shell – Mamoru Oshii’s iconic adaptation of the Shirow Masamune manga in which a cybernetic ally enhanced policewoman hunts a hacker known as the Puppet Master.

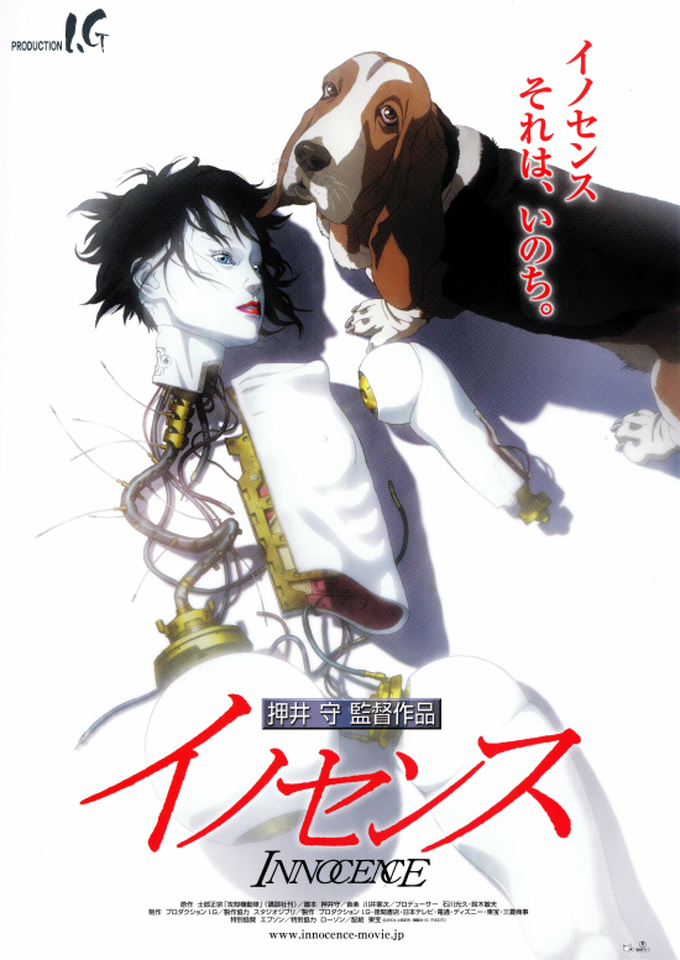

- Ghost in the Shell 2: Innocence – sequel to the original Ghost in the Shell set in the Hong Kong of 2032.

Independence (21st August)

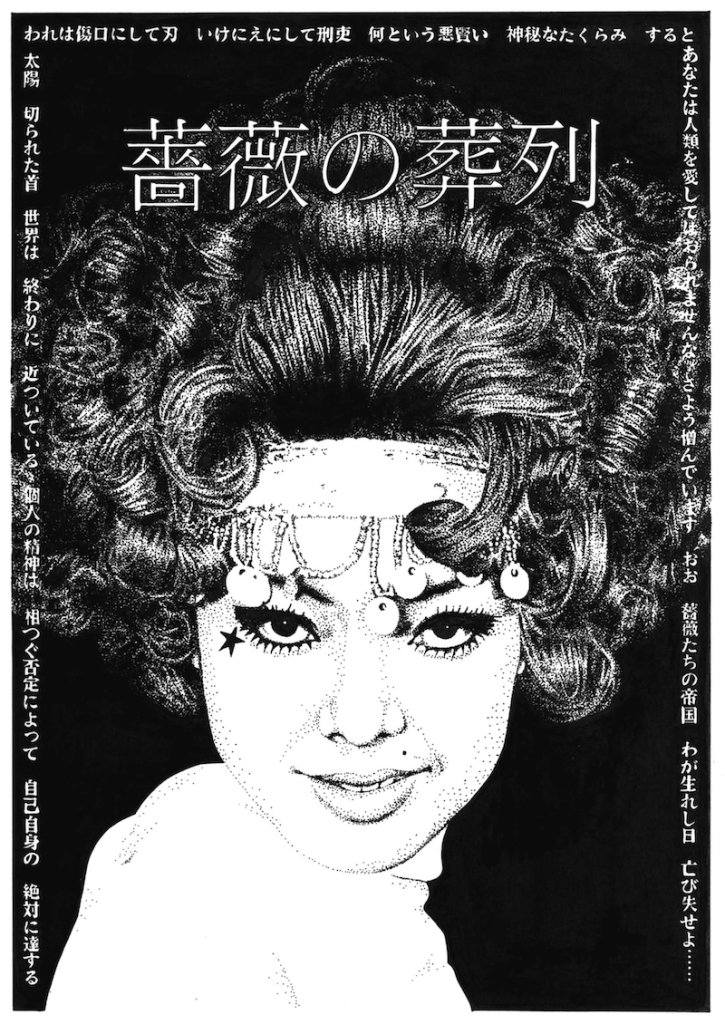

- Funeral Parade of Roses – Toshio Matsumoto’s avant-garde take on Oedipus Rex.

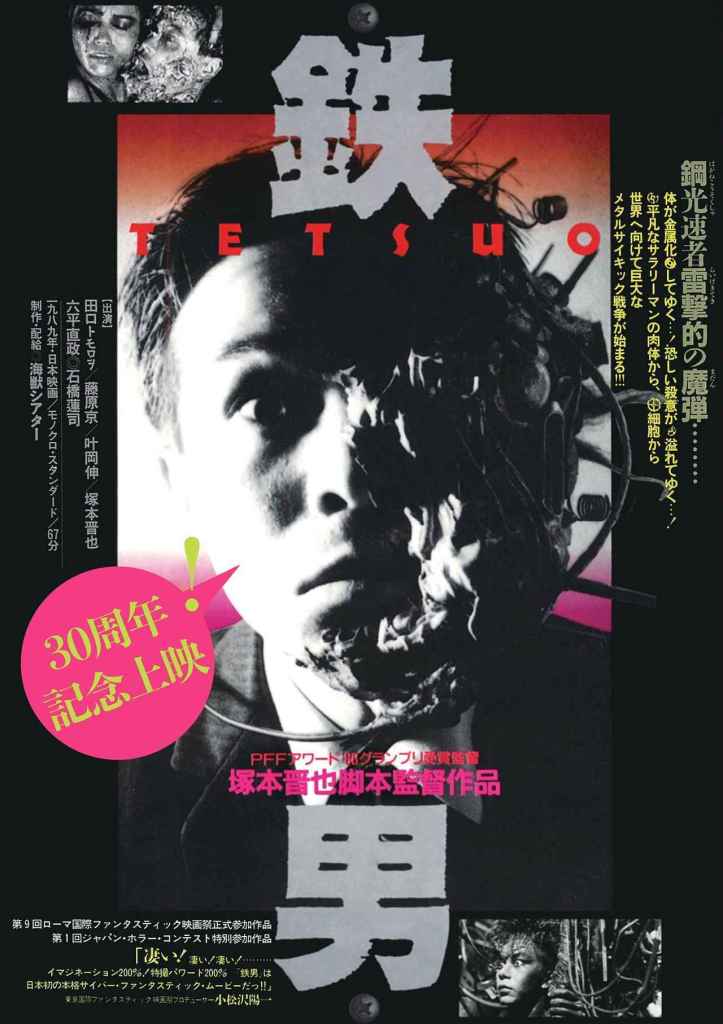

- Tetsuo: The Iron Man – surrealist body horror from Shinya Tsukamoto.

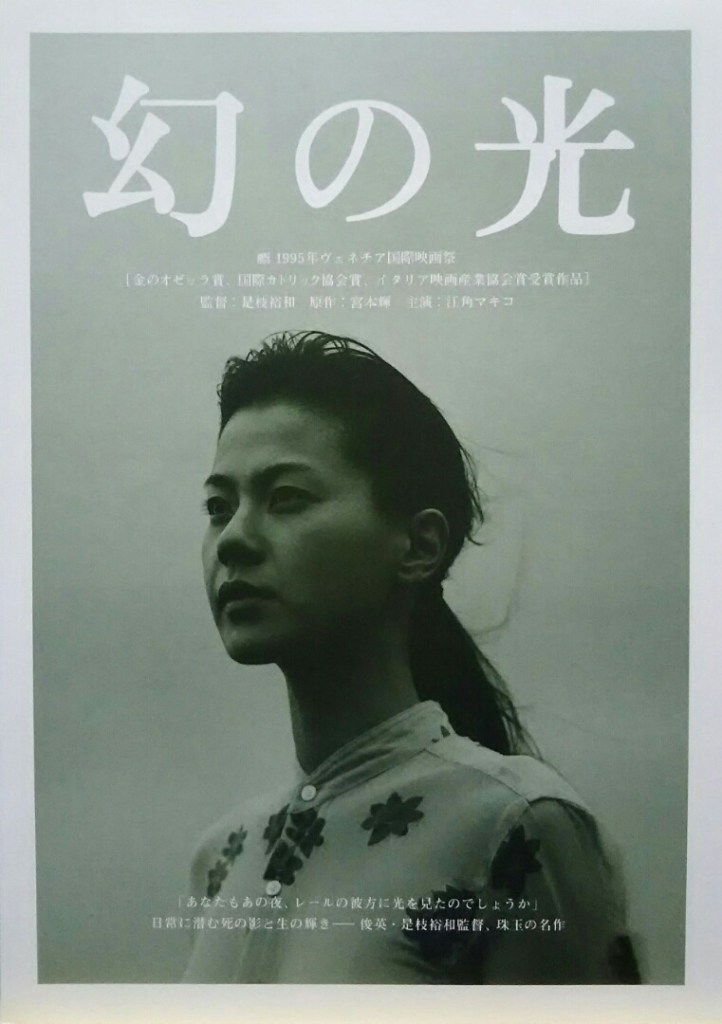

- Maborosi – a young widow struggles to come to terms with the apparent suicide of her husband in Hirokazu Koreeda’s debut feature.

- Sawako Decides – an aimless young woman struggles to find direction in her life in an early comedy from Yuya Ishii starring Hikari Mitsushima.

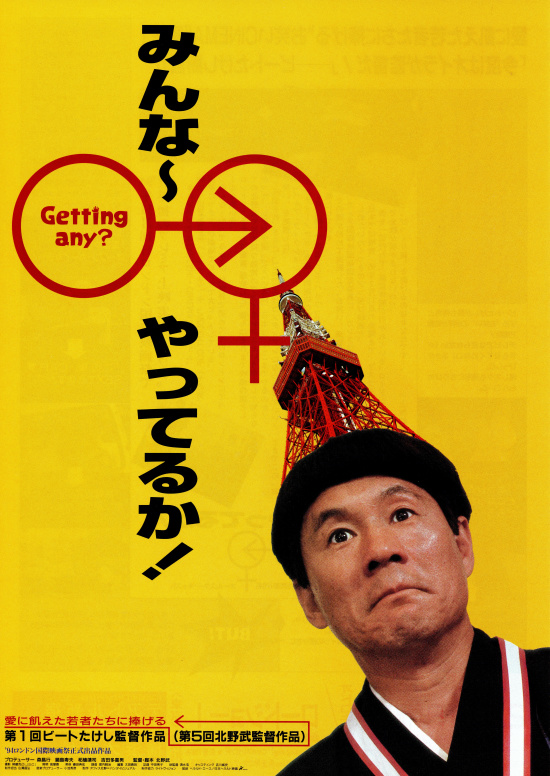

- Getting Any? – zany pop culture comedy from Takeshi Kitano in which a man goes to great lengths to get a car solely so he can have sex in it. Review.

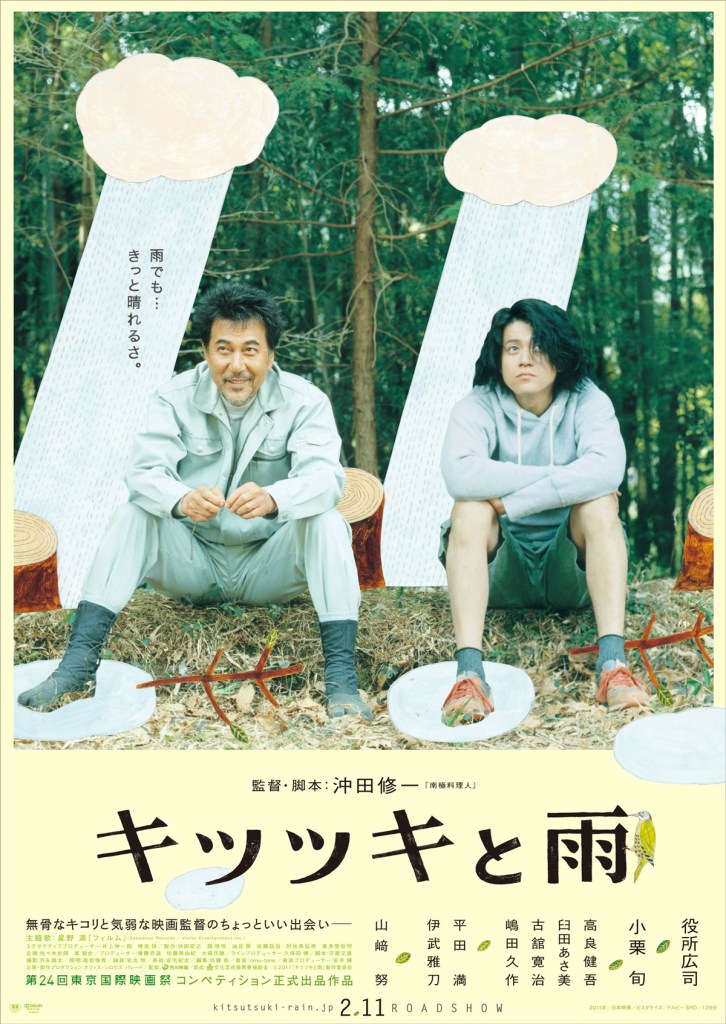

- The Woodsman and the Rain – comedy from Shuichi Okita in which a film director bonds with a lonely lumberjack while shooting a zombie movie.

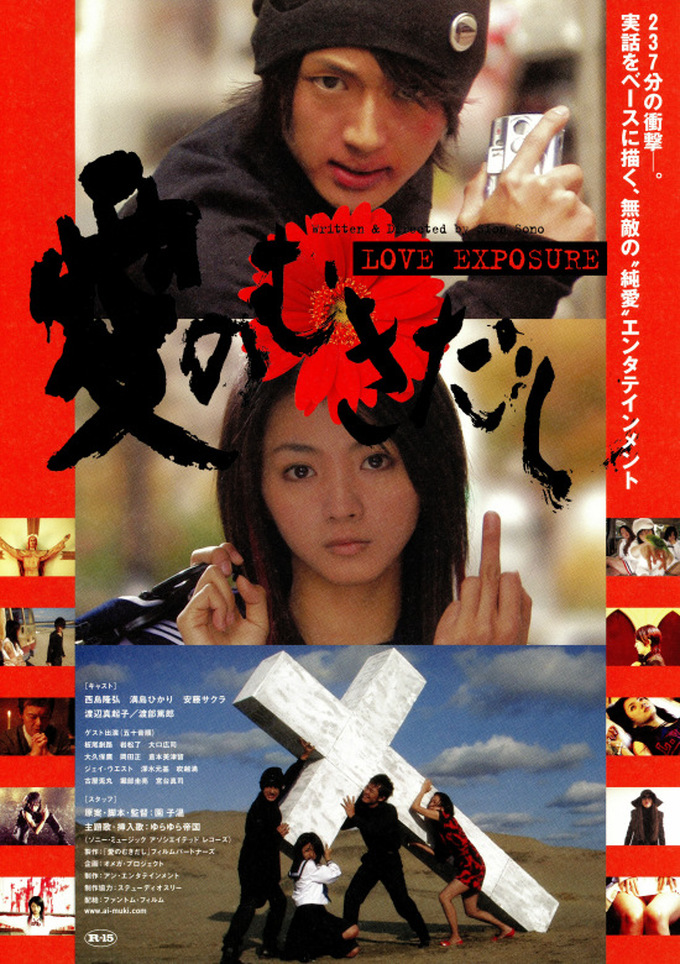

- Love Exposure – 4-hour epic from Sion Sono in which the son of a priest becomes obsessed with upskirt photography.

- The Mourning Forest – a bereaved mother bonds with the elderly resident of a care home where she works in an award winning drama from Naomi Kawase.

- A Scene at the Sea – poetic drama from Takeshi Kitano about a deaf refuse collector who becomes fixated on surfacing. Review.

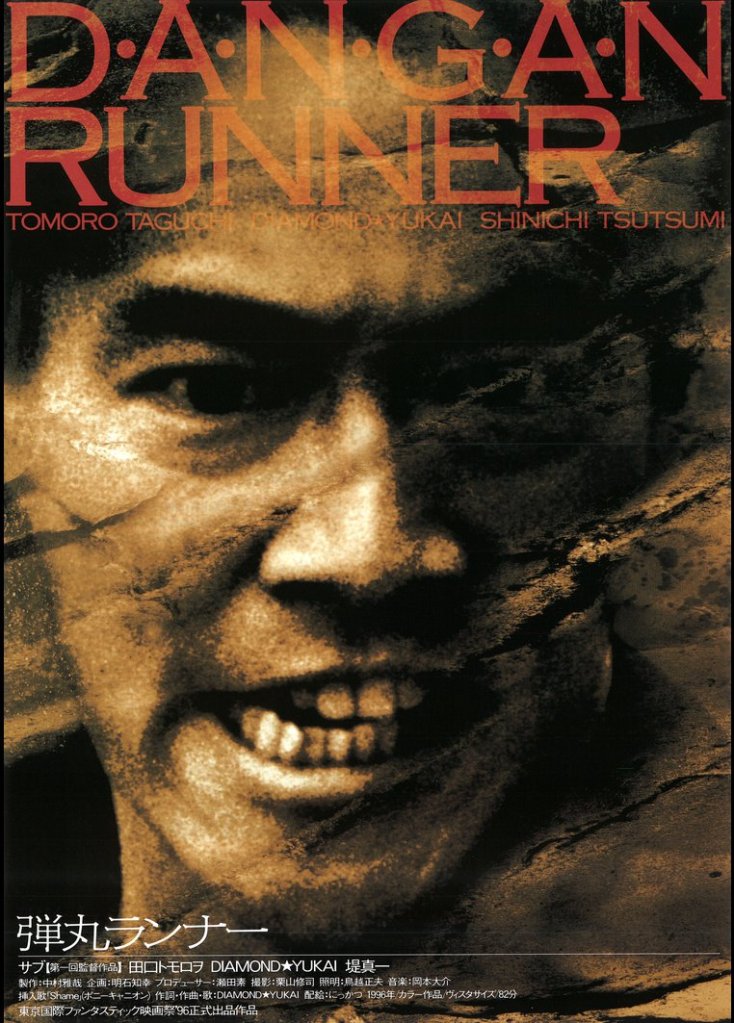

- Dangan Runner – three men ricochet towards an inevitable ending in the debut feature from SABU. Review.

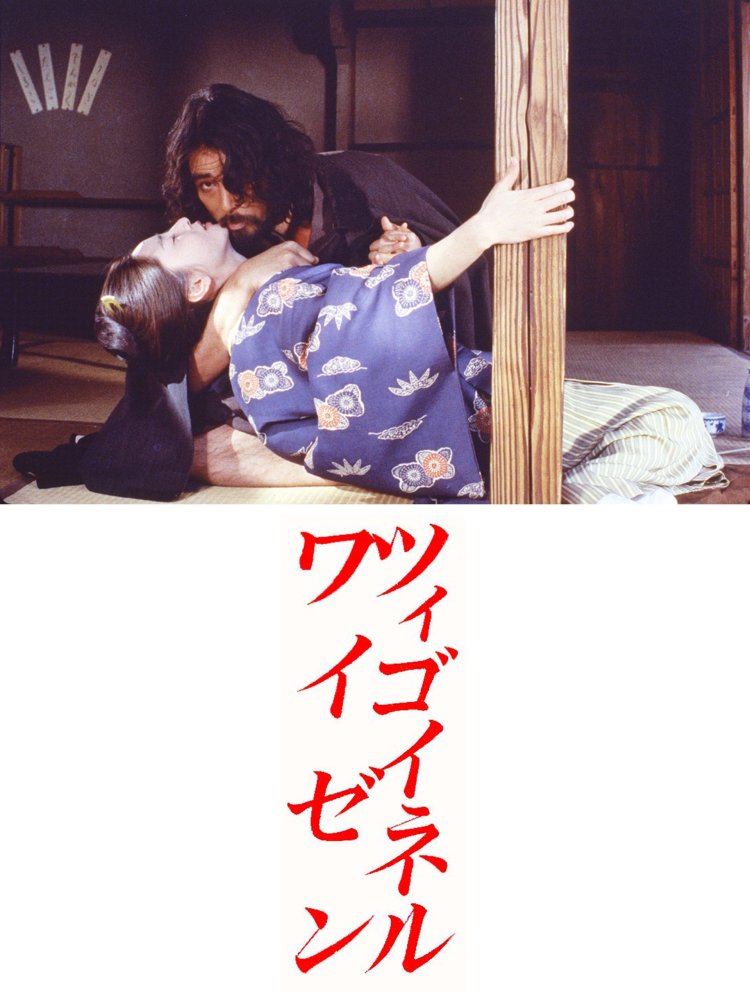

- Zigeunerweisen – surreal drama from Seijun Suzuki starring Yoshio Harada as a nomad on the run after being suspected of seducing and killing the wife of a fisherman.

- Shinjuku Triad Society – sleazy ’90s noir from Takashi Miike in which a mixed race policeman goes up against a Taiwanese gang over to discover his younger brother has joined them as a rookie lawyer. Review.

- Violent Cop – a rogue cop attuned to the ways of violence abandons all pretence of civility in pursuit of justice but encounters only nihilistic futility in Kitano’s Bubble-era noir. Review.

- Boiling Point – a disaffected young man finds himself on a self-destructive mission of vicarious vengeance but struggles to escape his sense of inferiority in Kitano’s deadpan exploration of explosive repression. Review.

- Sonatine – tired of the life, a veteran gangster ponders retirement but knows his brief island holiday is only a temporary respite from his nihilistic life of violence in Kitano’s melancholy existential drama. Review.

- A Lonely Cow Weeps at Dawn – pink film from Daisuke Goto in which a woman impersonates her senile father-in-law’s long gone favourite cow and allows him to milk her.

21st Century (18th September)

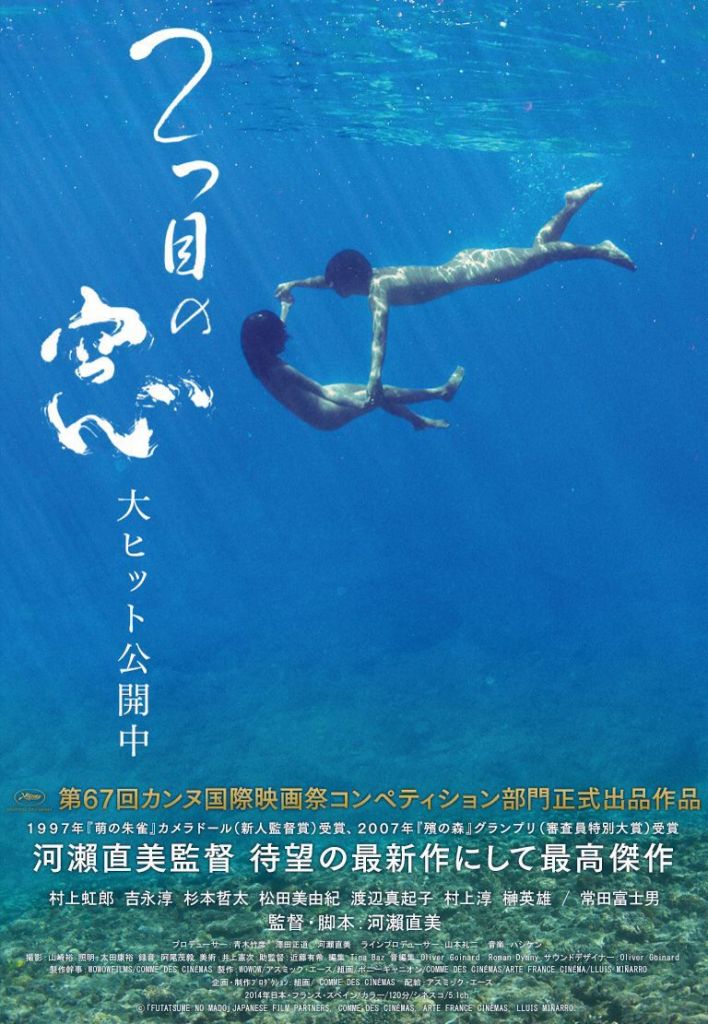

- Still the Water – island coming of age drama from Naomi Kawase. (not included in subscription, £3.50 to rent)

- Sweet Bean – a dorayaki salesman bonds with an old woman who helps him improve his bean paste in Naomi Kawase’s moving drama.

- Nobody Knows – siblings are left to fend for themselves when their mother abandons them in Hirokazu Koreeda’s gritty drama.

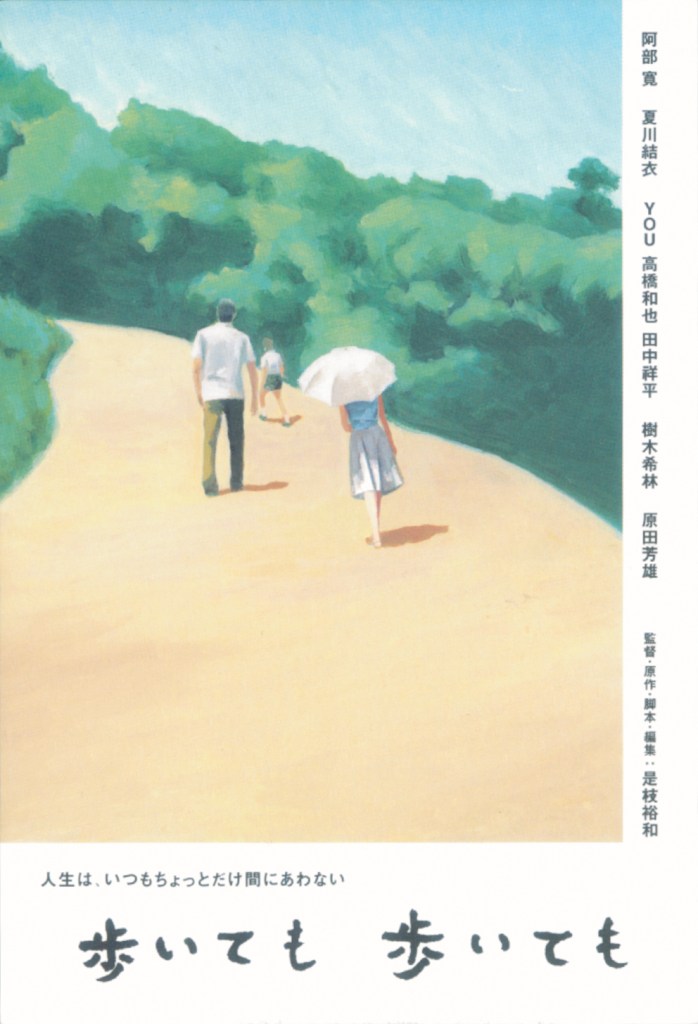

- Still Walking – Hirokazu Koreeda’s moving depiction of a typical family. Review.

- Cold Fish – Sion Sono’s gory serial killer drama inspired by a real life incident.

- Tokyo Tribe – a rap musical manga adaptation from Sion Sono.

- Mitsuko Delivers – a heavily pregnant woman returns to her home town and proceeds to solve everyone’s problems in Yuya Ishii’s cheerful comedy.

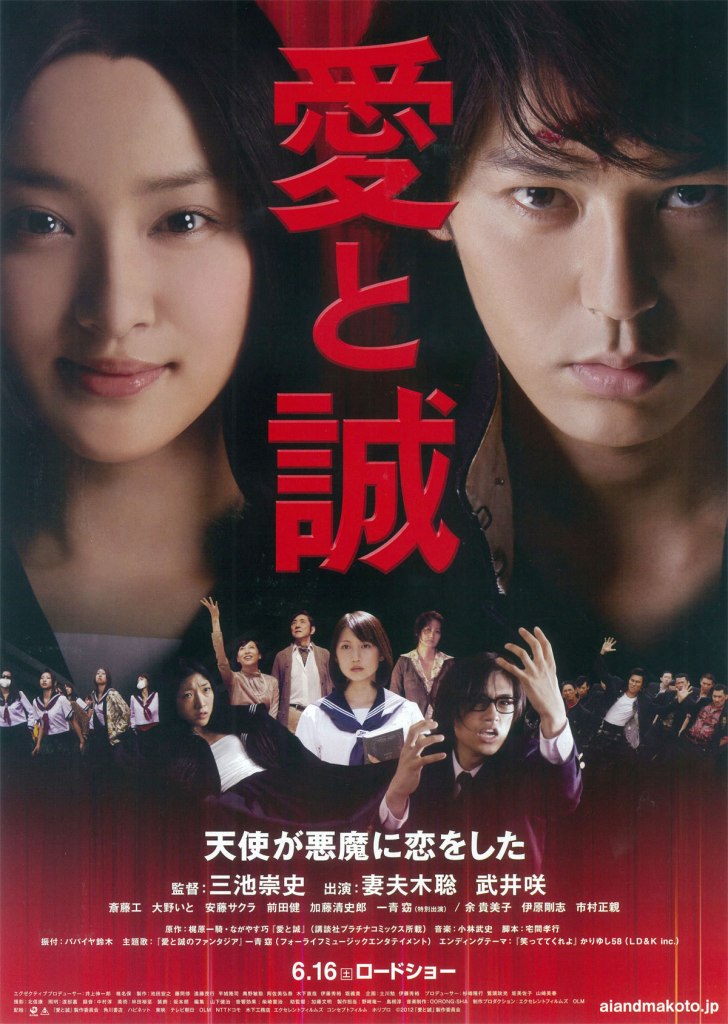

- For Love’s Sake – musical manga adaption celebrating the Showa era songbook from Takashi Miike.

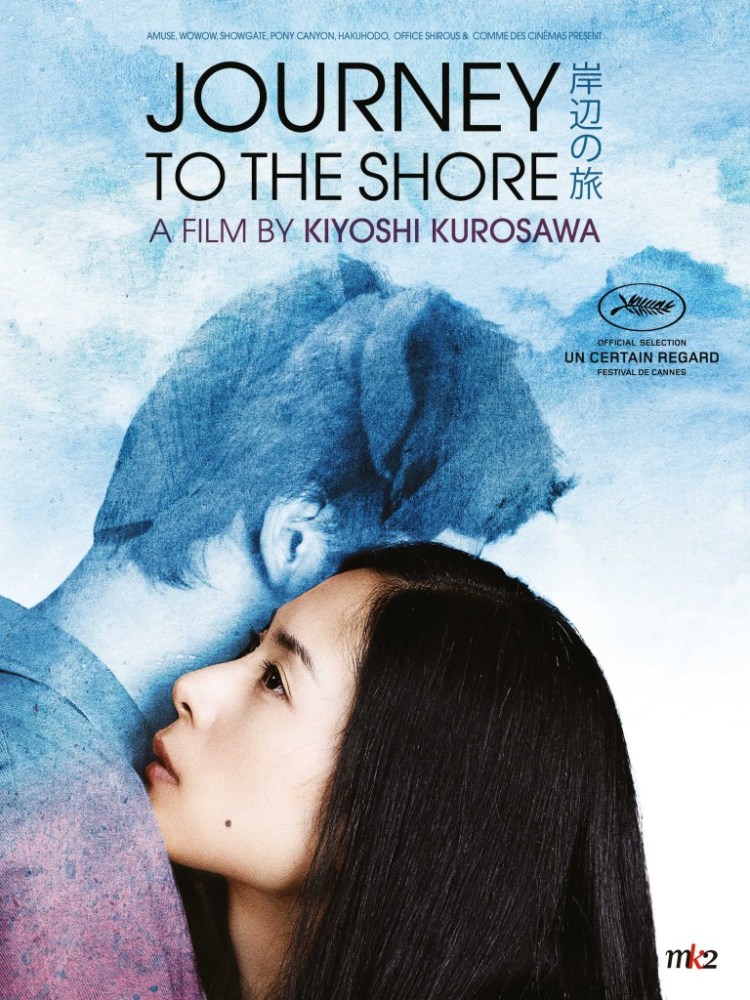

- Journey to the Shore – haunting romantic drama from Kiyoshi Kurosawa. Review.

- Creepy – Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s eerie mystery drama. Review.

- The Lust of Angels – edgy train groping drama from Nagisa Isogai.

- Harmonium – a family is torn apart by unexpected tragedy when a face from the past pays a visit in Koji Fukada’s probing drama. Review.

- Departures – a cellist accidentally takes a job as a traditional mortician but keeps his new occupation a secret in this Oscar-winning drama from 2008.

Early films 1894-1914 (12th October)

The BFI will also be showcasing restored gems from their archive featuring footage of turn of the century Japan.

- Japanese Dancers (1894) – rare footage of Japanese women performing an imperial dance.

- Ainus of Japan (1913) – footage depicting the indigenous people of Hokkaido.

- Japanese Festival (1910) – footage of the celebration of the 50th anniversary of Yokohama Harbour

- Shooting the Rapids on the River Ozu in Japan (1907) – 1907 river journey.

J-Horror (30th October)

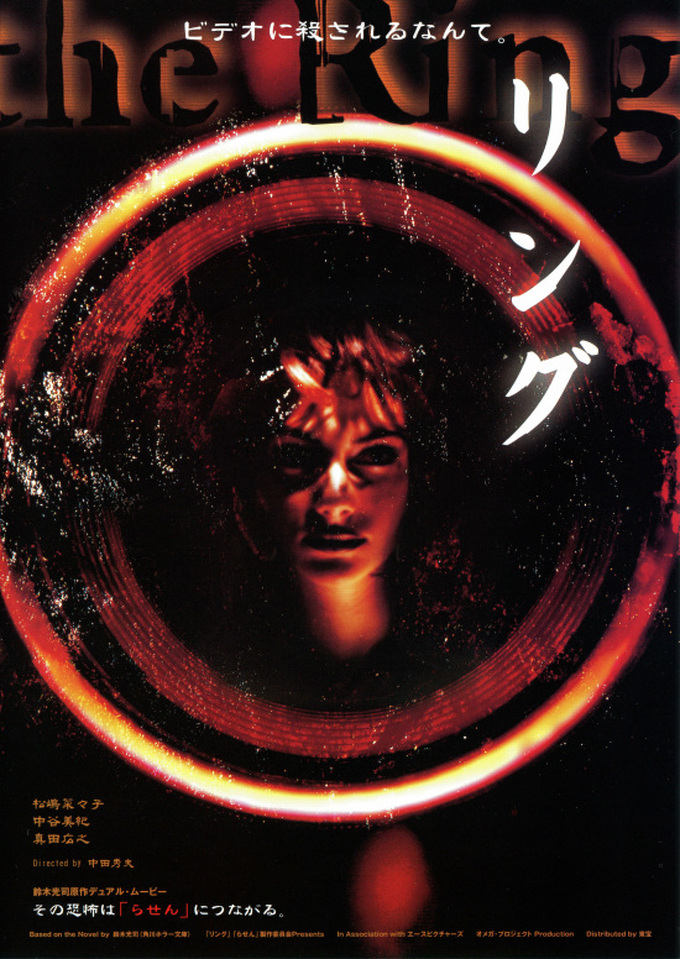

- Ring – a deadly curse is transmitted via videotape in Hideo Nakata’s J-horror classic.

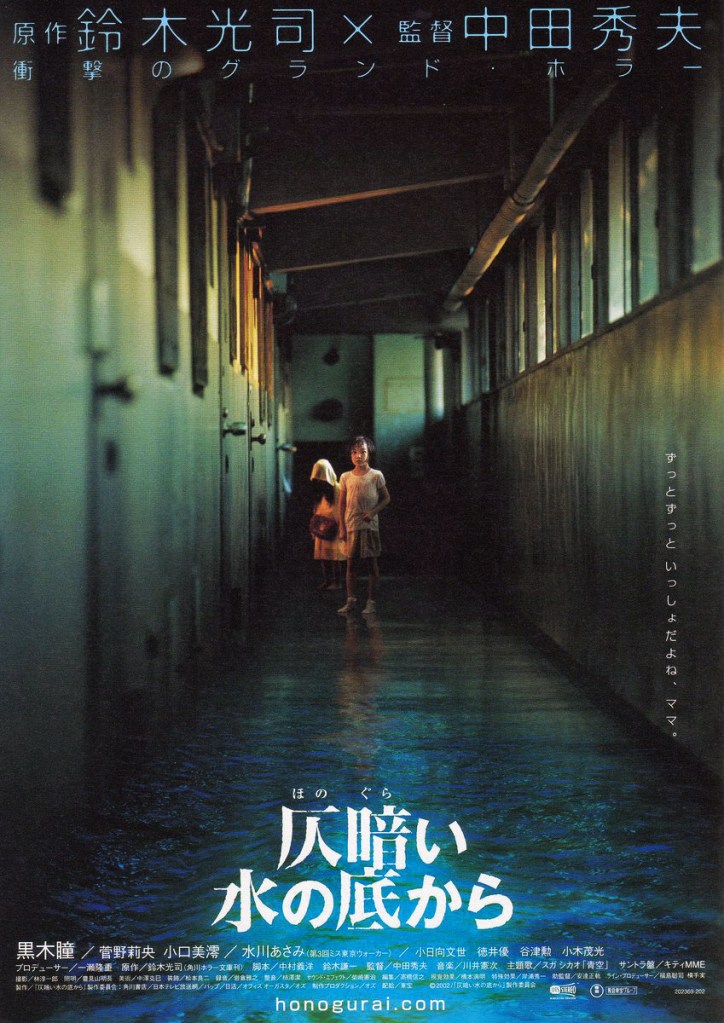

- Dark Water – a woman in the midst of a divorce and custody battle is haunted by the spectre of a lonely child in Hideo Nakata’s adaptation of the Koji Suzuki novel. Review.

- Audition – Takashi Miike’s deceptive drama begins as a gentle romcom before edging slowly towards the horrific.

- Gozu – truly strange yakuza horror comedy from Takashi Miike.

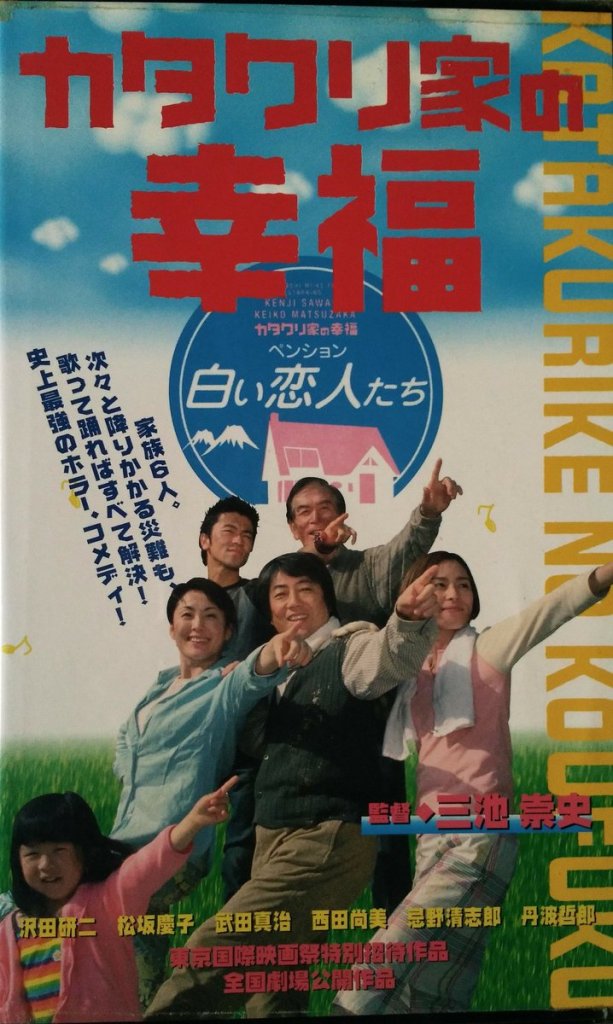

- The Happiness of the Katakuris – Takashi Miike’s strangely cheerful musical take on the Korean film The Quiet Family.

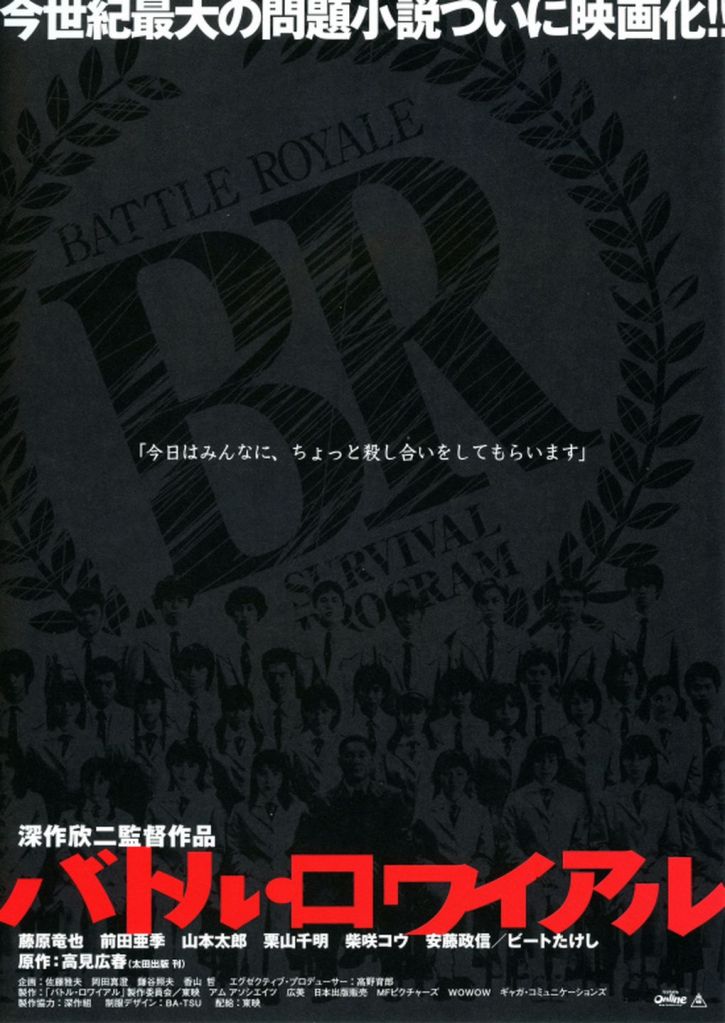

- Battle Royale – controversial drama from Kinji Fukasaku in which high school students are shipped to a remote island and forced to fight to the death.

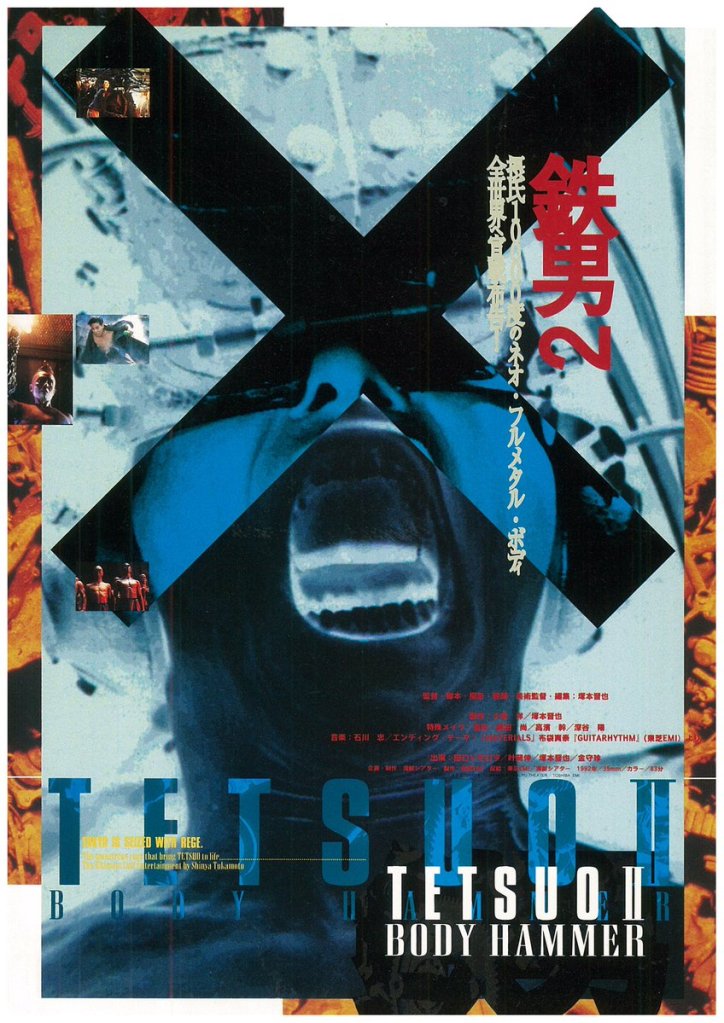

- Tetsuo II: Body Hammer – sequel to Shinya Tsukamoto’s cyberpunk body horror.

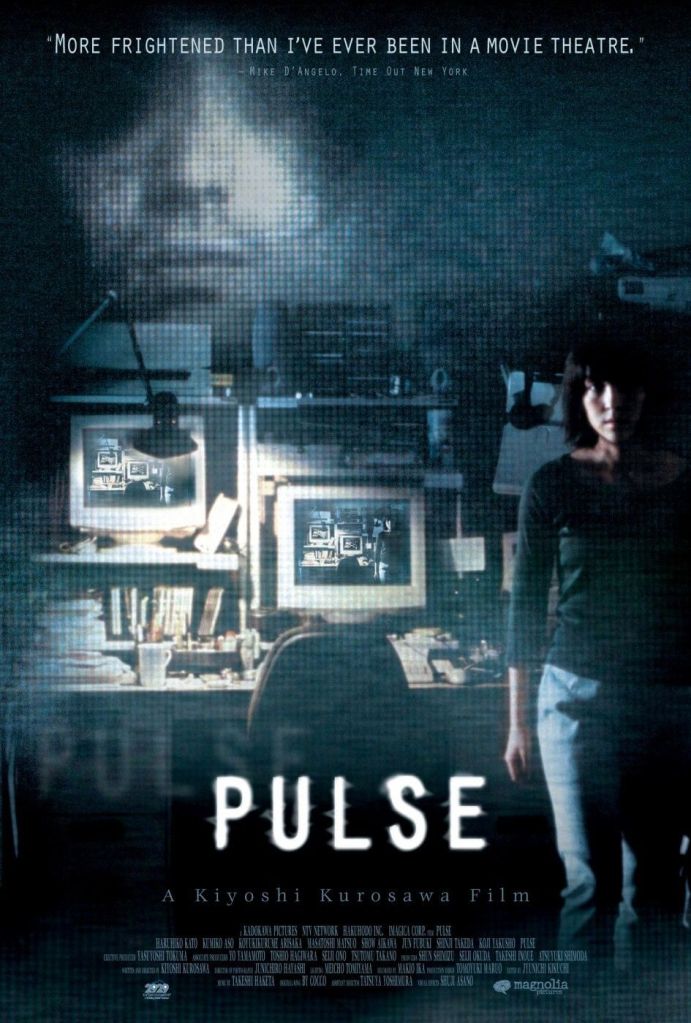

- Pulse – death is eternal loneliness in Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s tech fearing horror classic. Review.

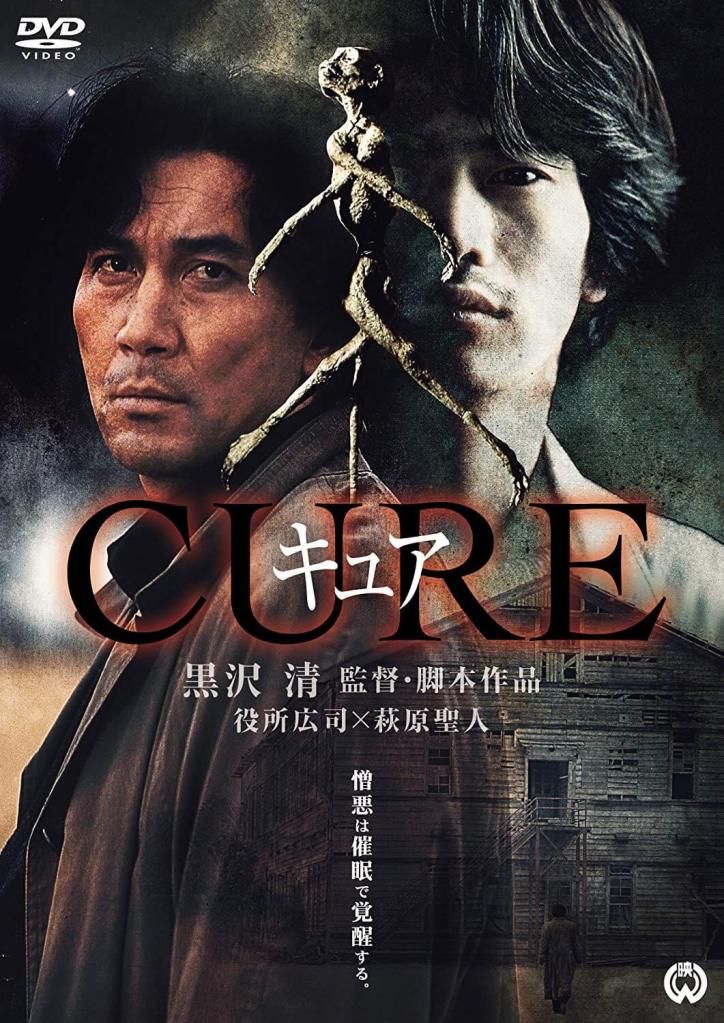

- Cure – Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s noirish horror starring Koji Yakusho as a detective investigating a series of bizarre murders.

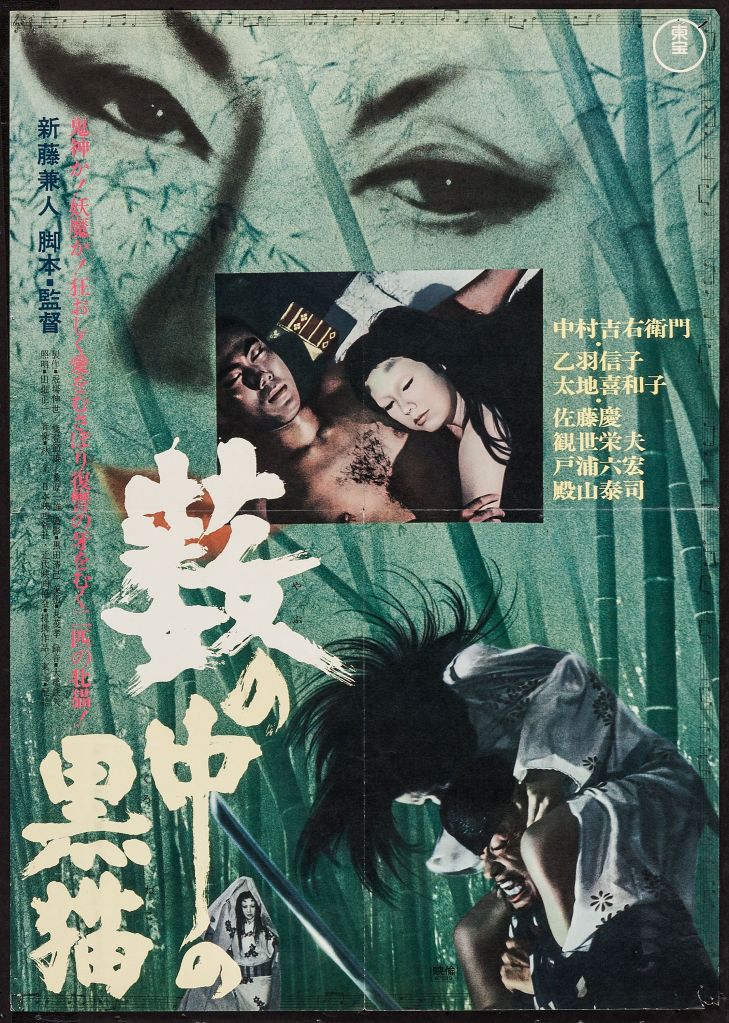

- Kuroneko – ghost cat film from Kaneto Shindo.

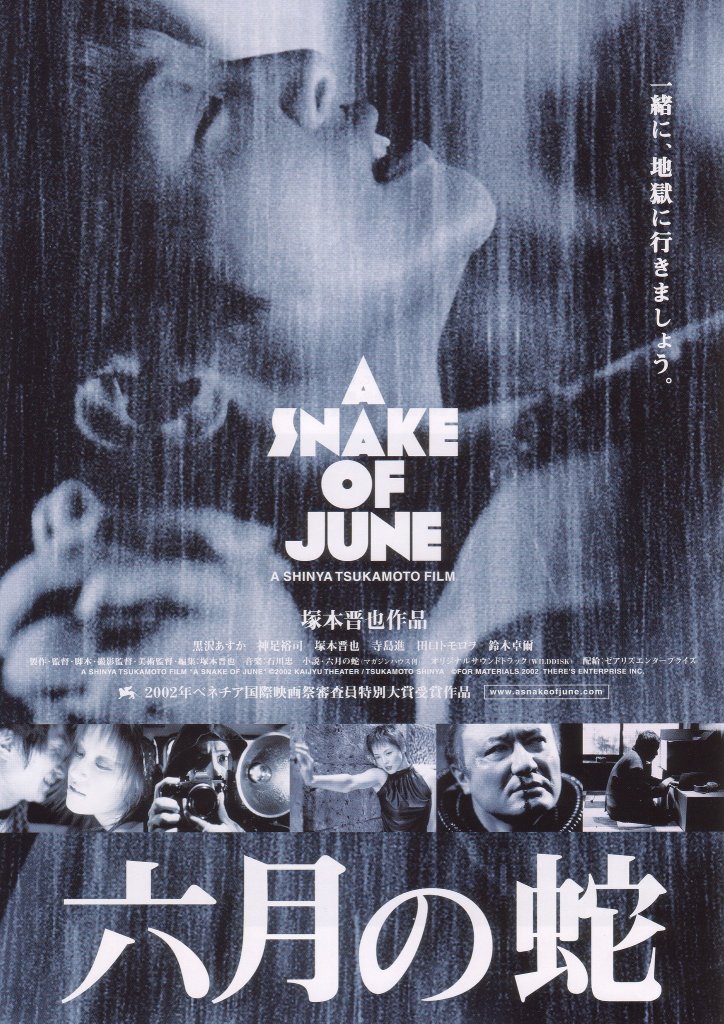

- Snake of June – erotic drama from Shinya Tsukamoto in which a mysterious man targets a repressed woman and forces her to engage in illicit sex acts.

BFI Southbank

The season will continue at the BFI Southbank once the venue reopens.

- Golden Age – season programmed by Alexander Jacoby and James Bell showcasing Japanese cinema from the 1930s to the 60s including work by Kenji Mizoguchi, Yasujiro Ozu, Mikio Naruse, and Akira Kurosawa, and starring Kinuyo Tanaka, Setsuko Hara, Hideko Takamine, and Toshiro Mifune.

- Radicals and Rebels – also curated by Alexander Jacoby and James Bell, the Radicals and Rebels strand focuses on film after 1964 from the New Wave to the genre classics of the ’90s including work by Seijun Suzuki, Nagisa Oshima, and Kiju (Yoshishige) Yoshida.

- 21st Century – contemporary classics co-presented by Japan Foundation and curated by Junko Takekawa.

- Anime – major two month season curated by Justin Johnson and Hanako Miyata showcasing modern masters such as Satoshi Kon, Mamoru Oshii, Makoto Shinkai, Mamoru Hosoda, and Naoko Yamada.

For the full details on this and other BFI seasons be sure to check out the BFI’s official website where you can also find a link to BFI Player. You can also keep up with all the latest news by following the BFI on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, and YouTube.