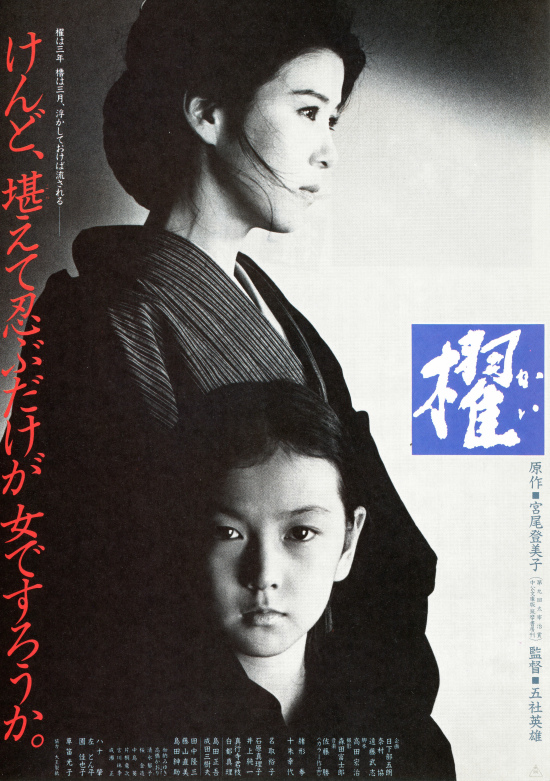

Until the later part of his career, Hideo Gosha had mostly been known for his violent action films centring on self destructive men who bore their sadnesses with macho restraint. During the 1980s, however, he began to explore a new side to his filmmaking with a string of female centred dramas focussing on the suffering of women which is largely caused by men walking the “manly way” of his earlier movies. Partly a response to his regular troupe of action stars ageing, Gosha’s new focus was also inspired by his failed marriage and difficult relationship with his daughter which convinced him that women can be just as devious and calculating as men. 1985’s Oar (櫂, Kai) is adapted from the novel by Tomiko Miyao – a writer Gosha particularly liked and identified with whose books also inspired Onimasa and The Geisha. Like Onimasa, Oar also bridges around twenty years of pre-war history and centres around a once proud man discovering his era is passing, though it finds more space for his long suffering wife and the children who pay the price for his emotional volatility.

Until the later part of his career, Hideo Gosha had mostly been known for his violent action films centring on self destructive men who bore their sadnesses with macho restraint. During the 1980s, however, he began to explore a new side to his filmmaking with a string of female centred dramas focussing on the suffering of women which is largely caused by men walking the “manly way” of his earlier movies. Partly a response to his regular troupe of action stars ageing, Gosha’s new focus was also inspired by his failed marriage and difficult relationship with his daughter which convinced him that women can be just as devious and calculating as men. 1985’s Oar (櫂, Kai) is adapted from the novel by Tomiko Miyao – a writer Gosha particularly liked and identified with whose books also inspired Onimasa and The Geisha. Like Onimasa, Oar also bridges around twenty years of pre-war history and centres around a once proud man discovering his era is passing, though it finds more space for his long suffering wife and the children who pay the price for his emotional volatility.

Kochi, 1914 (early Taisho), Iwago (Ken Ogata) is a kind hearted man living beyond his means. Previously a champion wrestler, he now earns his living as a kind of procurer for a nearby geisha house, chasing down poor girls and selling them into prostitution, justifying himself with the excuse that he’s “helping” the less fortunate who might starve if it were not for the existence of the red light district. He dislikes this work and finds it distasteful, but shows no signs of stopping. At home he has a wife and two sons whom he surprises one day by returning home with a little girl he “rescued” at the harbour after seeing her beaten by man who, it seemed, was trying to sell her to Chinese brokers who are notorious for child organ trafficking.

Iwago names the girl “Kiku” thanks to the chrysanthemums on her kimono and entrusts her to his irritated wife, Kiwa (Yukiyo Toake), who tries her best but Kiku is obviously traumatised by her experiences, does not speak, and takes a long time to become used to her new family circumstances. Parallel to his adoption of Kiku, Iwago is also working on a sale of a girl of a similar age who ends up staying in the house for a few days before moving to the red light district. Toyo captures Kiwa’s heart as she bears her sorry fate stoically, pausing only to remark on her guilt at eating good white rice three times a day at Iwago’s knowing that her siblings are stuck at home with nothing.

Iwago’s intentions are generally good, but his “manly” need for control and his repressed emotionality proceed to ruin his family’s life. He may say that poverty corrupts a person’s heart and his efforts are intended to help prevent the birth of more dysfunctional families, but deep down he finds it hard to reconcile his distasteful occupation with his traditional ideas of masculine chivalry. Apparently “bored” with the long suffering Kiwa he fathers a child with another woman which he then expects her to raise despite the fact that she has already left the family home after discovering the affair. Predictably her love for him and for the children brings her home, but Iwago continues to behave in a domineering, masterly fashion which is unlikely to repair his once happy household.

Kiwa is the classic long suffering wife, bearing all of Iwago’s mistreatments with stoic perseverance until his blatant adultery sends her running from marriage to refuge at the home of her brother. Despite the pain and humilation, Kiwa still loves, respects, and supports her husband, remembering him as he once was rather than the angry, frustrated brute which he has become. Despite her original hesitance, Kiwa’s maternal warmth makes a true daughter of Kiku and keeps her bonded to the eldest and more sensitive of her two sons, Ryutaro, even if the loose cannon that is Kentaro follows in his step-father’s footsteps as an unpredictable punk. Her goodheartedness later extends to Iwago’s illegitimate daughter Ayako whom she raises as her own until Iwago cruelly decides to separate them. For all of Iwago’s bluster and womanising, ironically enough Kiwa truly is the only woman for him as he realises only when she determines to leave. Smashing the relics of his “manly” past – his wrestling photos and trophies, Iwago is forced to confront the fact that his own macho posturing has cost him the only thing he ever valued.

Gosha tones down the more outlandish elements which contributed to his reputation as a “vulgar” director but still finds space for female nudity and frank sexuality as Iwago uses and misuses the various women who come to him for help or shelter. More conventional in shooting style than some of Gosha’s other work from the period and lacking any large scale or dramatic fight scenes save for one climactic ambush, Oar acts more as a summation of Gosha’s themes up until the mid-80s – men destroy themselves through their need to be men but also through destroying the women who have little choice but to stand back and watch them do it. Unless, like Kiwa, they realise they have finally had enough.

Short clip from near the beginning of the film (no subtitles)

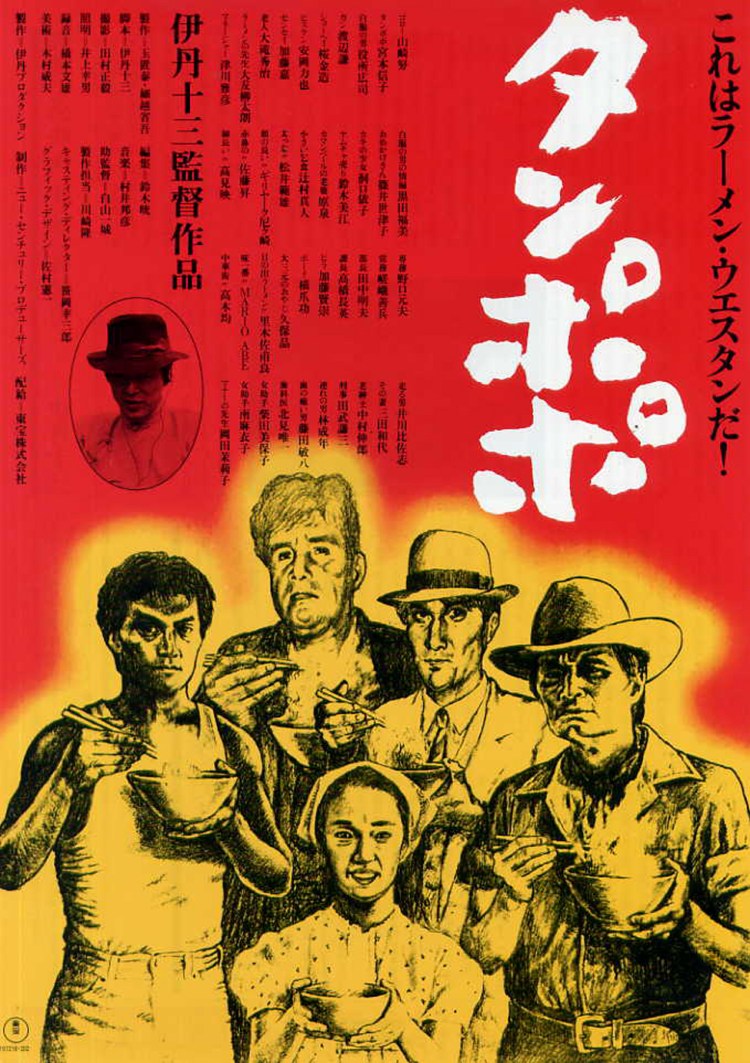

Some people love ramen so much that the idea of a “bad” bowl hardly occurs to them – all ramen is, at least, ramen. Then again, some love ramen so much that it’s almost a religious experience, bound up with ritual and the need to do things properly. A brief vignette at the beginning of Juzo Itami’s Tampopo (タンポポ) introduces us to one such ramen expert who runs through the proper way of enjoying a bowl of noodle soup which involves a lot of talking to your food whilst caressing it gently before finally consuming it with the utmost respect. Ramen is serious business, but for widowed mother Tampopo it’s a case of the watched pot never boiling. Thanks to a cowboy loner and a few other waifs and strays who eventually become friends and allies, Tampopo is about to get some schooling in the quest for the perfect noodle whilst the world goes on around her. Food becomes something used and misused but remains, ultimately, the source of all life and the thing which unites all living things.

Some people love ramen so much that the idea of a “bad” bowl hardly occurs to them – all ramen is, at least, ramen. Then again, some love ramen so much that it’s almost a religious experience, bound up with ritual and the need to do things properly. A brief vignette at the beginning of Juzo Itami’s Tampopo (タンポポ) introduces us to one such ramen expert who runs through the proper way of enjoying a bowl of noodle soup which involves a lot of talking to your food whilst caressing it gently before finally consuming it with the utmost respect. Ramen is serious business, but for widowed mother Tampopo it’s a case of the watched pot never boiling. Thanks to a cowboy loner and a few other waifs and strays who eventually become friends and allies, Tampopo is about to get some schooling in the quest for the perfect noodle whilst the world goes on around her. Food becomes something used and misused but remains, ultimately, the source of all life and the thing which unites all living things.

Still most closely associated with his debut feature Hausu – a psychedelic haunted house musical, Nobuhiko Obayashi’s affinity for youthful subjects made him a great fit for the burgeoning Kadokawa idol phenomenon. Maintaining his idiosyncratic style, Obayashi worked extensively in the idol arena eventually producing such well known films as

Still most closely associated with his debut feature Hausu – a psychedelic haunted house musical, Nobuhiko Obayashi’s affinity for youthful subjects made him a great fit for the burgeoning Kadokawa idol phenomenon. Maintaining his idiosyncratic style, Obayashi worked extensively in the idol arena eventually producing such well known films as  The popularity of idol movies had started to wane by the late ‘80s and if this 1988 effort from Masanobu Deme is anything to go by, some of their youthful innocence had also started to depart. Starring Kumiko Goto, only 14 at the time, The Girl in the Glass (ガラスの中の少女, Glass no Naka no Shojo) is an adaptation of a novel by Yorichika Arima which had previously been filmed all the way back in

The popularity of idol movies had started to wane by the late ‘80s and if this 1988 effort from Masanobu Deme is anything to go by, some of their youthful innocence had also started to depart. Starring Kumiko Goto, only 14 at the time, The Girl in the Glass (ガラスの中の少女, Glass no Naka no Shojo) is an adaptation of a novel by Yorichika Arima which had previously been filmed all the way back in

Haruki Kadokawa dominated much of mainstream 1980s cinema with his all encompassing media empire perpetuated by a constant cycle of movies, books, and songs all used to sell the other. 1984’s Someday, Someone Will be Killed (いつか誰かが殺される, Itsuka Dareka ga Korosareru) is another in this familiar pattern adapting the Kadokawa teen novel by Jiro Akagawa and starring lesser idol Noriko Watanabe in one of her rare leading performances in which she also sings the similarly titled theme song. The third film from Korean/Japanese director Yoichi Sai, Someday, Someone Will be Killed is an impressive mix of everything which makes the world Kadokawa idol movies so enticing as the heroine finds herself unexpectedly at the centre of an ongoing international conspiracy protected only by a selection of underground drop outs but faces her adversity with typical perkiness and determination safe in the knowledge that nothing really all that bad is going to happen.

Haruki Kadokawa dominated much of mainstream 1980s cinema with his all encompassing media empire perpetuated by a constant cycle of movies, books, and songs all used to sell the other. 1984’s Someday, Someone Will be Killed (いつか誰かが殺される, Itsuka Dareka ga Korosareru) is another in this familiar pattern adapting the Kadokawa teen novel by Jiro Akagawa and starring lesser idol Noriko Watanabe in one of her rare leading performances in which she also sings the similarly titled theme song. The third film from Korean/Japanese director Yoichi Sai, Someday, Someone Will be Killed is an impressive mix of everything which makes the world Kadokawa idol movies so enticing as the heroine finds herself unexpectedly at the centre of an ongoing international conspiracy protected only by a selection of underground drop outs but faces her adversity with typical perkiness and determination safe in the knowledge that nothing really all that bad is going to happen. When AnimEigo decided to release Hideo Gosha’s Taisho/Showa era yakuza epic Onimasa (鬼龍院花子の生涯, Kiryuin Hanako no Shogai), they opted to give it a marketable but ill advised tagline – A Japanese Godfather. Misleading and problematic as this is, the Japanese title Kiryuin Hanako no Shogai also has its own mysterious quality in that it means “The Life of Hanako Kiryuin” even though this, admittedly hugely important, character barely appears in the film. We follow instead her adopted older sister, Matsue (Masako Natsume), and her complicated relationship with our title character, Onimasa, a gang boss who doesn’t see himself as a yakuza but as a chivalrous man whose heart and duty often become incompatible. Reteaming with frequent star Tatsuya Nakadai, director Hideo Gosha gives up the fight a little, showing us how sad the “manly way” can be on one who finds himself outplayed by his times. Here, anticipating Gosha’s subsequent direction, it’s the women who survive – in large part because they have to, by virtue of being the only ones to see where they’re headed and act accordingly.

When AnimEigo decided to release Hideo Gosha’s Taisho/Showa era yakuza epic Onimasa (鬼龍院花子の生涯, Kiryuin Hanako no Shogai), they opted to give it a marketable but ill advised tagline – A Japanese Godfather. Misleading and problematic as this is, the Japanese title Kiryuin Hanako no Shogai also has its own mysterious quality in that it means “The Life of Hanako Kiryuin” even though this, admittedly hugely important, character barely appears in the film. We follow instead her adopted older sister, Matsue (Masako Natsume), and her complicated relationship with our title character, Onimasa, a gang boss who doesn’t see himself as a yakuza but as a chivalrous man whose heart and duty often become incompatible. Reteaming with frequent star Tatsuya Nakadai, director Hideo Gosha gives up the fight a little, showing us how sad the “manly way” can be on one who finds himself outplayed by his times. Here, anticipating Gosha’s subsequent direction, it’s the women who survive – in large part because they have to, by virtue of being the only ones to see where they’re headed and act accordingly.

Looking at the poster and its “A Most “Oshare” Movie” tagline, you’d assume Cats in Park Avenue (公園通りの猫たち, Koendori no Nekotachi) to be a very stylish story about some fashionable felines living on an uptown street comparable to the famous New York landmark but the title is entirely coincidental as it’s a literal translation of the Japanese and just means the cats live on a street near the park. These cats are full on alley cats, scrappy and free, roaming the rooftops of Shibuya and not giving a damn about whatever it is cats are supposed to do. Ostensibly a throw away young adult movie about a group of dance students and their obsession with a gang of local street cats, Cats in Park Avenue takes on a surprisingly individualist message as the virtues of freedom and validity of life outside the mainstream are resolutely reinforced through cute animation and nonsensical musical sequences.

Looking at the poster and its “A Most “Oshare” Movie” tagline, you’d assume Cats in Park Avenue (公園通りの猫たち, Koendori no Nekotachi) to be a very stylish story about some fashionable felines living on an uptown street comparable to the famous New York landmark but the title is entirely coincidental as it’s a literal translation of the Japanese and just means the cats live on a street near the park. These cats are full on alley cats, scrappy and free, roaming the rooftops of Shibuya and not giving a damn about whatever it is cats are supposed to do. Ostensibly a throw away young adult movie about a group of dance students and their obsession with a gang of local street cats, Cats in Park Avenue takes on a surprisingly individualist message as the virtues of freedom and validity of life outside the mainstream are resolutely reinforced through cute animation and nonsensical musical sequences.