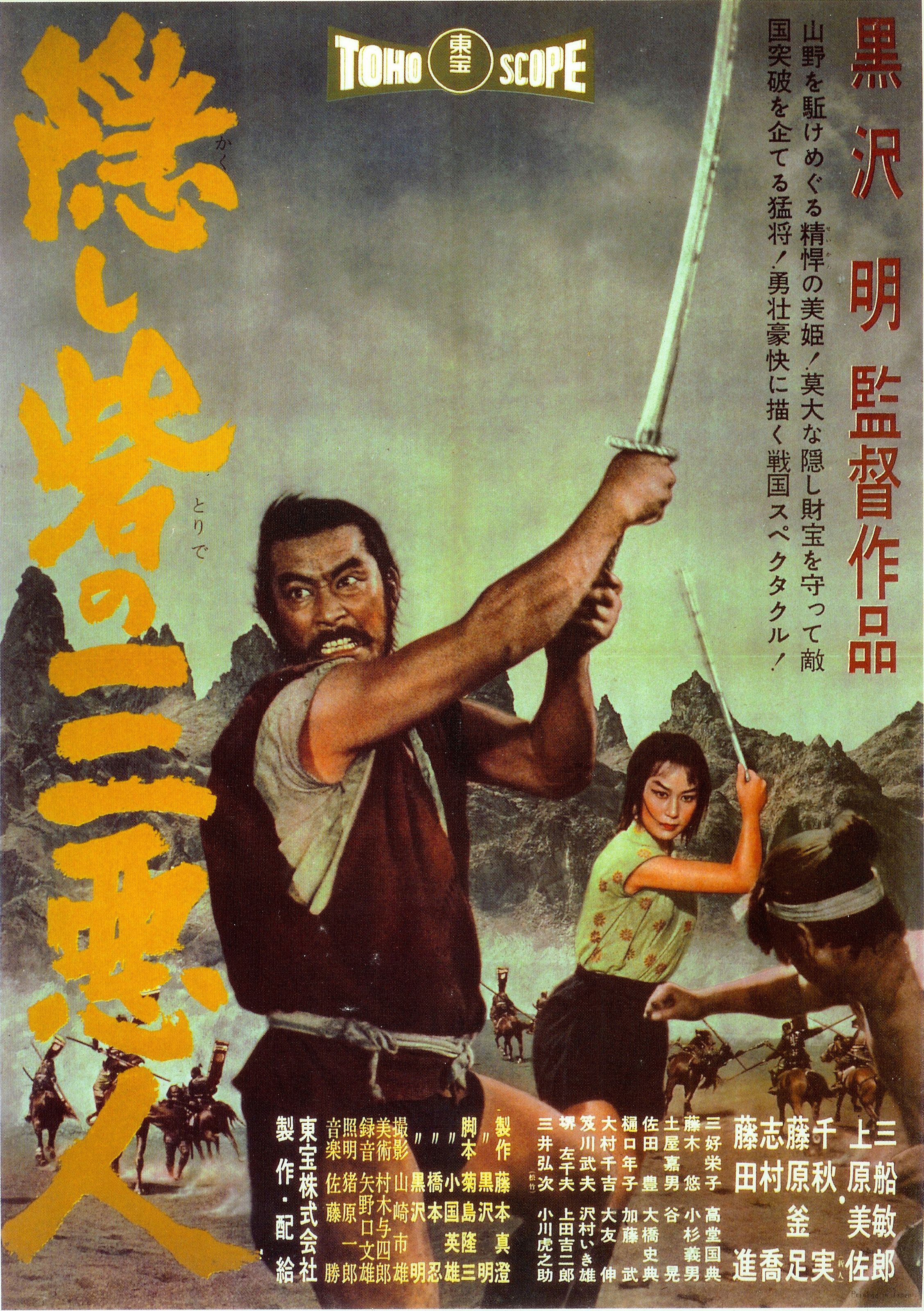

“Your kindness will harm you” a well-meaning retainer advises his charge, but in the end it is her kindness which saves her along with numerous others in Akira Kurosawa’s Sengoku-era epic, The Hidden Fortress (隠し砦の三悪人, Kakushi Toride no San Akunin). Largely told from the point of view of two bumbling peasants trying to get rich quick by exploiting the hierarchal fluidity of a time of war, the film nevertheless cuts against the grain of the democratic era in advocating not so much the destruction of the class-bound feudal order as benevolent authority.

This can quite clearly be seen in the dynamic figure of displaced princess Yuki (Misa Uehara), the successor of her routed clan protected by a hidden fortress in the mountains which she must eventually leave. Her female servant laments that her father raised her as a boy which has given her a haughty and dominant manner at odds with the polite submissiveness usually expected of upperclass women. While often exerting her authority, she is otherwise uncomfortable with the uncritical servitude of her retainers, chief among them the talented general Makabe (Toshiro Mifune) who sacrificed the life of his own sister, allowing her to be executed in Yuki’s place buying them some time. “Kofuyu was 16. I am 16. What difference is there in our souls?” she asks, yet even if she believes their souls are equal she is not quite so egalitarian as to forget her position or the power and privilege that comes with it.

Nevertheless, hers is an authority that is tempered by compassion and in the end chosen. Her salvation comes in speaking her mind to an enemy retainer, Tadokoro (Susumu Fujita), who has been savagely beaten by his own lord for losing a duel with Makabe who, to the mind of some, humiliated him with kindness in refusing to take his life leaving him to live in defeat. Yuki says she doesn’t know who is stupider, Tadokoro or his lord, for never would she punish a man in such a way simply for losing to an enemy. She tells him that there is another way, and that he need not serve a lord who does not serve him leading Tadokoro to defect and choose to follow her instead.

She also inspires confidence in a young woman she insists on redeeming after discovering that she is a former member of the Akizuka clan sold into sexual slavery after being taken prisoner by the Yamane. Kurosawa presents the girl with a dilemma on realising that the mysterious woman who saved her is the fugitive princess, knowing that she could betray her and pocket the gold, but finds her resolving to serve Yuki all the more. In a moment of irony, we learn that the girl was bought for five silver coins, the same amount of money a wealthy traveller offers for Makabe’s horse, but displeases her master in refusing to speak or serve customers. For Yuki he offers gold, though withdraws on being told that she is mute. Knowing that she would be unable to disguise her speech or accent which would instantly give her away as a haughty princess, Makabe convinces her to stay silent though as she tells him he cannot make her heart mute too.

Even the peasants, oblivious to her true identity, view Yuki as part of the spoils insisting that they should be entitled to a third of her too and at one point preparing to rape her only to be fought off by the rescued girl. “We can rely on their greed” Makabe had said, knowing that their material desires make them easy to manipulate and that their loyalties are otherwise fickle. Matashichi (Kamatari Fujiwara) and his friend Tahei (Minoru Chiaki) sold their houses in their village to buy armour in the hope of achieving social mobility through distinguishing themselves in war, but have largely been humiliated, robbed of their armour, mistaken for captured members of the enemy, and forced to dig the graves of others. They pledge eternal friendship but their bond is continually disrupted by the promise of monetary gain. They fall out over a moral quandary, one willing to plunder the body of a fallen soldier and the other not, while even on reuniting squabbling about how to divide the money first deciding it should be equal and immediately disagreeing as soon as they get their hands on it. At the film’s conclusion it rests on Yuki to play mother, telling them that they must be good and share the boon she’s given them equally without complaint each then too only quick to be generous insisting that the other can keep it.

The implication is still, however, that Matashichi and Tahei should return to their village to live as peasants while Yuki assumes her place in a castle no longer hidden as its ruler. Order has returned and the old system remains in place, all that changes is that this is now a compassionate autocracy ruled by a benevolent lord who views her subjects lives as equal to her own yet not perhaps their status. Where it might prompt Tadokoro to conclude that he need serve no lord at all for there should be no leaders only equals, the film concludes that a leader should be just and if they are not they should not be followed. Then again, the disagreement between firm friends Matashichi and Tahei is ended when they each have enough and no longer find themselves fighting for a bigger slice of the pie content in the validation of their equality. As Makabe puts it, heavy is the head that wears the crown. Yuki’s suffering is in the responsibility of rebuilding her clan though she does so with compassion and empathy ruling with respect rather than fear or austerity. Kurosawa utilises the novel scope format to hint at the wide open vistas that extend ahead of the peasants as they make their way towards the castle in search of gold only to leave with something that while more valuable may also shine so brightly as to blind them to the inherent inequalities of the feudal order.

The Hidden Fortress screens at the BFI Southbank, London on 20th & 27th January 2023 as part of the Kurosawa season.