Yasushi Sato, a Hakodate native, has provided the source material for some of the best films of recent times including Mipo O’s The Light Shines Only There and Nobuhiro Yamashita’s Over the Fence but it has to be said that his world view is anything but positive. Kazuyoshi Kumakiri takes on Sketches of Kaitan City (海炭市叙景, Kaitanshi Jokei) inspired by a collection of short stories left unfinished on Sato’s death by suicide in 1990. Despite the late bubble era setting of the stories (now updated to the present day), his Kaitan (eerily close to the real life Hakodate) is a place of decline and hopelessness, populated by the disillusioned and despairing.

Yasushi Sato, a Hakodate native, has provided the source material for some of the best films of recent times including Mipo O’s The Light Shines Only There and Nobuhiro Yamashita’s Over the Fence but it has to be said that his world view is anything but positive. Kazuyoshi Kumakiri takes on Sketches of Kaitan City (海炭市叙景, Kaitanshi Jokei) inspired by a collection of short stories left unfinished on Sato’s death by suicide in 1990. Despite the late bubble era setting of the stories (now updated to the present day), his Kaitan (eerily close to the real life Hakodate) is a place of decline and hopelessness, populated by the disillusioned and despairing.

The first story concerns a brother and sister whose lives have been defined by the local shipbuilding industry. Since their father was killed in a dockside fire, older brother Futa (Pistol Takehara) has been taking care of his little sister Honami (Mitsuki Tanimura) and now works at the docks himself. Times being what they are, the company is planning to close three docks with mass layoffs inevitable. The workers strike but are unable to win more than minor concessions leaving Futa unable to continue providing for himself or his sister.

Similar tales of societal indifference follow as an old lady living alone with her beloved cat is hounded by a developer (Takashi Yamanaka) desperate to buy her home. Across town the owner of the planetarium (Kaoru Kobayashi) is living a life of quiet desperation, suspecting that his bar hostess wife (Kaho Minami) is having an affair. Meanwhile a gas canister salesman (Ryo Kase) is trying to branch out but having little success, and a tram driver dwells on his relationship with his estranged son.

Economic and social concerns become intertwined as increasing financial instability chips away at the foundations of otherwise sound family bonds. Futa’s situation is one of true desperation now that he’s lost the only job he’s ever had and is ill equipped to get a new one even if there were anything going in this town which revolves entirely around its port.

Yet other familial bonds are far from sound to begin with. The gas canister salesman, going against his father’s wishes in trying to diversify with a series of water purifiers he believes will be a guaranteed earner because of the need to replace filters, takes out his various frustrations through astonishing acts of violence against his wife who then passes on the legacy of abuse to his son, Akira (You Koyama). Resentful towards his father and embarrassed by his lack of success with the water filters, the gas canister salesman threatens to explode but unexpectedly finding himself on the receiving end of violence, he is forced into a reconsideration of his way of life – saving one family member, but perhaps betraying another.

The gas canister salesman is not the only one to have a difficult relationship with his child. The planetarium owner cannot seem to connect with his own sullen offspring and is treated like an exile within his own home while the tram driver no longer speaks to his son who is apparently still angry and embarrassed that his mother worked in a hostess bar.

Yet for all of this real world disillusionment, despair takes on a poetic quality as the planetarium owner spends his days literally staring at the stars – even if they are fake. The gas canister salesman’s son, Akira, becomes a frequent visitor, excited by the idea of the telescope and dreaming of a better, far away world only to have his hopes literally dashed by his parents, themselves already teetering on the brink of an abyss. Futa’s lifelong love has been with shipping – the company officials are keen to sell the line that it’s all about the boats and an early scene of jubilation following the launch of a recently completed vessel would seem to bear that out, but when it comes down to it the values are far less pure than a simple love of craftsmanship. Kaitan City is a place where dreams go to die and hope is a double edged sword.

There are, however, small shoots of positivity. The old lady welcomes her cat back into her arms, discovering that it is pregnant and stroking it gently, reassuring it that everything will be OK and she will take care of the new cat family. Signs of life appear, even if drowned out by the noise of ancient engines and the sound of the future marching quickly in the opposite direction. Bleak yet beautifully photographed, Sketches of Kaitan City perfectly captures the post-industrial malaise and growing despair of those excluded from economic prosperity, left with nothing other than false promises and misplaced hope to guide the way towards some kind of survival.

Original trailer (no subtitles)

Every love story is a ghost story, as the aphorism made popular (though not perhaps coined) by David Foster Wallace goes. For The Tale of Nishio (ニシノユキヒコの恋と冒険, Nishino Yukihiko no Koi to Boken), adapted from the novel by Hiromi Kawakami, this is a literal truth as the hero dies not long after the film begins and then returns to visit an old lover, only to find her gone, having ghosted her own family including a now teenage daughter. The Japanese title, which is identical to Kawakami’s novel, means something more like Yukihiko Nishino’s Adventures in Love which might give more of an indication into his repeated failures to find the “normal” family life he apparently sought, but then his life is a kind of cautionary tale offered up as a fable. What looks like kindness sometimes isn’t, and things done for others can in fact be for the most selfish of reasons.

Every love story is a ghost story, as the aphorism made popular (though not perhaps coined) by David Foster Wallace goes. For The Tale of Nishio (ニシノユキヒコの恋と冒険, Nishino Yukihiko no Koi to Boken), adapted from the novel by Hiromi Kawakami, this is a literal truth as the hero dies not long after the film begins and then returns to visit an old lover, only to find her gone, having ghosted her own family including a now teenage daughter. The Japanese title, which is identical to Kawakami’s novel, means something more like Yukihiko Nishino’s Adventures in Love which might give more of an indication into his repeated failures to find the “normal” family life he apparently sought, but then his life is a kind of cautionary tale offered up as a fable. What looks like kindness sometimes isn’t, and things done for others can in fact be for the most selfish of reasons.

History books make for the grimmest reading, subjective as they often are. Science fiction can rarely improve upon the already existing evidence of humanity’s dark side, but Genocidal Organ (

History books make for the grimmest reading, subjective as they often are. Science fiction can rarely improve upon the already existing evidence of humanity’s dark side, but Genocidal Organ ( “It’s not all about tofu!” screams the heroine of Akanezora: Beyond the Crimson Sky (あかね空), a film which is all about tofu. Like tofu though, it has its own subtle flavour, gradually becoming richer by absorbing the spice of life. Based on a novel by Ichiriki Yamamoto, Akanezora is co-scripted by veteran of the Japanese New Wave, Masahiro Shinoda and directed by Masaki Hamamoto who had worked with Shinoda on Owl’s Castle and Spy Sorge prior to the director’s retirement in 2003. Like the majority of Shinoda’s work, Akanezora takes place in the past but echoes the future as it takes a sideways look at the nation’s most representative genre – the family drama. Fathers, sons, legacy and innovation come together in the story of a young man travelling from an old capital to a new one with a traditional craft he will have to make his own in order to succeed.

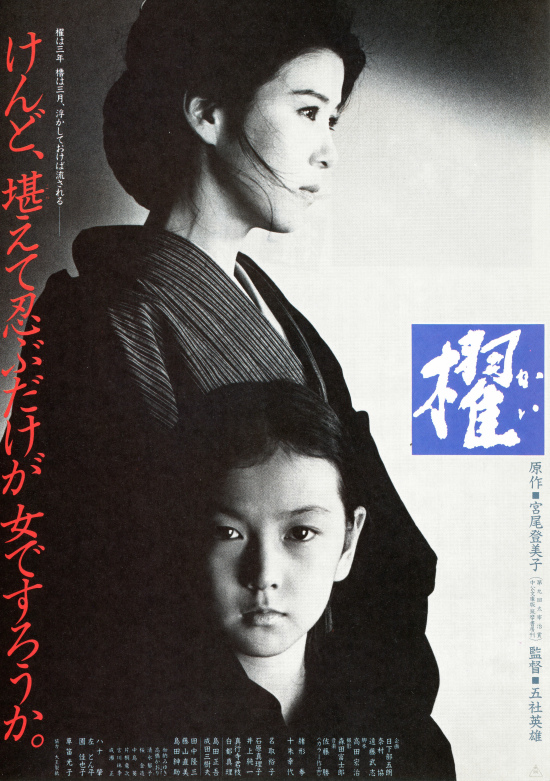

“It’s not all about tofu!” screams the heroine of Akanezora: Beyond the Crimson Sky (あかね空), a film which is all about tofu. Like tofu though, it has its own subtle flavour, gradually becoming richer by absorbing the spice of life. Based on a novel by Ichiriki Yamamoto, Akanezora is co-scripted by veteran of the Japanese New Wave, Masahiro Shinoda and directed by Masaki Hamamoto who had worked with Shinoda on Owl’s Castle and Spy Sorge prior to the director’s retirement in 2003. Like the majority of Shinoda’s work, Akanezora takes place in the past but echoes the future as it takes a sideways look at the nation’s most representative genre – the family drama. Fathers, sons, legacy and innovation come together in the story of a young man travelling from an old capital to a new one with a traditional craft he will have to make his own in order to succeed. Until the later part of his career, Hideo Gosha had mostly been known for his violent action films centring on self destructive men who bore their sadnesses with macho restraint. During the 1980s, however, he began to explore a new side to his filmmaking with a string of female centred dramas focussing on the suffering of women which is largely caused by men walking the “manly way” of his earlier movies. Partly a response to his regular troupe of action stars ageing, Gosha’s new focus was also inspired by his failed marriage and difficult relationship with his daughter which convinced him that women can be just as devious and calculating as men. 1985’s Oar (櫂, Kai) is adapted from the novel by Tomiko Miyao – a writer Gosha particularly liked and identified with whose books also inspired

Until the later part of his career, Hideo Gosha had mostly been known for his violent action films centring on self destructive men who bore their sadnesses with macho restraint. During the 1980s, however, he began to explore a new side to his filmmaking with a string of female centred dramas focussing on the suffering of women which is largely caused by men walking the “manly way” of his earlier movies. Partly a response to his regular troupe of action stars ageing, Gosha’s new focus was also inspired by his failed marriage and difficult relationship with his daughter which convinced him that women can be just as devious and calculating as men. 1985’s Oar (櫂, Kai) is adapted from the novel by Tomiko Miyao – a writer Gosha particularly liked and identified with whose books also inspired  The criticism levelled most often against Japanese cinema is its readiness to send established franchises to the big screen. Manga adaptations make up a significant proportion of mainstream films, but most adaptations are constructed from scratch for maximum accessibility to a general audience – sometimes to the irritation of the franchise’s fans. When it comes to the cinematic instalments of popular TV shows the question is more difficult but most attempt to make some concession to those who are not familiar with the already established universe. Mozu (劇場版MOZU) does not do this. It makes no attempt to recap or explain itself, it simply continues from the end of the second series of the TV drama in which the “Mozu” or shrike of the title was resolved leaving the shady spectre of “Daruma” hanging for the inevitable conclusion.

The criticism levelled most often against Japanese cinema is its readiness to send established franchises to the big screen. Manga adaptations make up a significant proportion of mainstream films, but most adaptations are constructed from scratch for maximum accessibility to a general audience – sometimes to the irritation of the franchise’s fans. When it comes to the cinematic instalments of popular TV shows the question is more difficult but most attempt to make some concession to those who are not familiar with the already established universe. Mozu (劇場版MOZU) does not do this. It makes no attempt to recap or explain itself, it simply continues from the end of the second series of the TV drama in which the “Mozu” or shrike of the title was resolved leaving the shady spectre of “Daruma” hanging for the inevitable conclusion. Kiyoshi Kurosawa has taken a turn for the romantic in his later career. Both 2013’s Real (リアル 完全なる首長竜の日, Real: Kanzen Naru Kubinagaryu no Hi) and

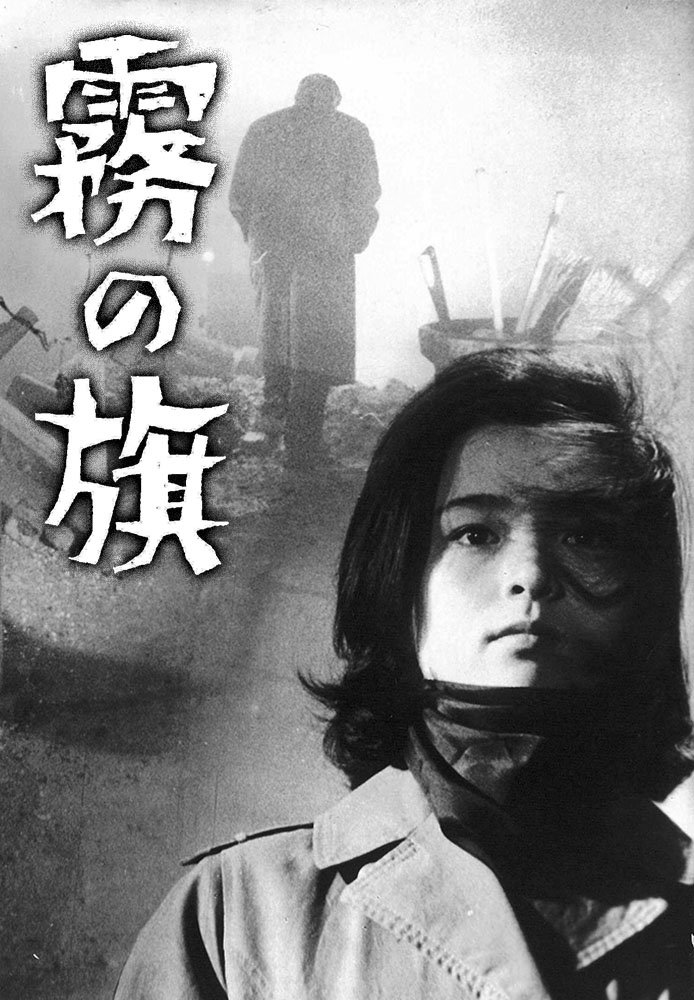

Kiyoshi Kurosawa has taken a turn for the romantic in his later career. Both 2013’s Real (リアル 完全なる首長竜の日, Real: Kanzen Naru Kubinagaryu no Hi) and  In theory, we’re all equal under the law, but the business of justice is anything but egalitarian. Yoji Yamada is generally known for his tearjerking melodramas or genial comedies but Flag in the Mist (霧の旗, Kiri no Hata) is a rare step away from his most representative genres, drawing inspiration from America film noir and adding a touch of typically Japanese cynical humour. Based on a novel by Japanese mystery master Seicho Matsumoto, Flag in the Mist is a tale of hopeless, mutually destructive revenge which sees a murderer walk free while the honest but selfish pay dearly for daring to ignore the poor in need of help. A powerful message in the increasing economic prosperity of 1965, but one that leaves no clear path for the successful revenger.

In theory, we’re all equal under the law, but the business of justice is anything but egalitarian. Yoji Yamada is generally known for his tearjerking melodramas or genial comedies but Flag in the Mist (霧の旗, Kiri no Hata) is a rare step away from his most representative genres, drawing inspiration from America film noir and adding a touch of typically Japanese cynical humour. Based on a novel by Japanese mystery master Seicho Matsumoto, Flag in the Mist is a tale of hopeless, mutually destructive revenge which sees a murderer walk free while the honest but selfish pay dearly for daring to ignore the poor in need of help. A powerful message in the increasing economic prosperity of 1965, but one that leaves no clear path for the successful revenger. Japan’s political climate had become difficult by 1938 with militarism in full swing. Young men were disappearing from their villages and being shipped off to war, and growing economic strife also saw young women sold into prostitution by their families. Cinema needed to be escapist and aspirational but it also needed to reflect the values of the ruling regime. Adapted from a novel by Katsutaro Kawaguchi, Aizen Katsura (愛染かつら) is an attempt to marry both of these aims whilst staying within the realm of the traditional romantic melodrama. The values are modern and even progressive, to a point, but most importantly they imply that there is always room for hope and that happy endings are always possible.

Japan’s political climate had become difficult by 1938 with militarism in full swing. Young men were disappearing from their villages and being shipped off to war, and growing economic strife also saw young women sold into prostitution by their families. Cinema needed to be escapist and aspirational but it also needed to reflect the values of the ruling regime. Adapted from a novel by Katsutaro Kawaguchi, Aizen Katsura (愛染かつら) is an attempt to marry both of these aims whilst staying within the realm of the traditional romantic melodrama. The values are modern and even progressive, to a point, but most importantly they imply that there is always room for hope and that happy endings are always possible. What would you give to live another day? What did you give to live this day? What did you take? Adapting the novel by Genki Kawamura, Akira Nagai takes a step back from the broad comedy of

What would you give to live another day? What did you give to live this day? What did you take? Adapting the novel by Genki Kawamura, Akira Nagai takes a step back from the broad comedy of