Jo Shishido played his fare share of icy hitmen, but they rarely made it through such seemingly inexorable events as the hero of Takashi Nomura’s A Colt is My Passport (拳銃は俺のパスポート, Colt wa Ore no Passport). The actor, known for his boyishly chubby face puffed up with the aid of cheek implants, floated around the lower end of Nikkatsu’s A-list but by 1967 his star was on the wane even if he still had his pick of cooler than cool tough guys in Nikkatsu’s trademark action B-movies. Mixing western and film noir, A Colt is My Passport makes a virtue of Japan’s fast moving development, heartily embracing the convenience of a society built around the idea of disposability whilst accepting the need to keep one step ahead of the rubbish truck else it swallow you whole.

Jo Shishido played his fare share of icy hitmen, but they rarely made it through such seemingly inexorable events as the hero of Takashi Nomura’s A Colt is My Passport (拳銃は俺のパスポート, Colt wa Ore no Passport). The actor, known for his boyishly chubby face puffed up with the aid of cheek implants, floated around the lower end of Nikkatsu’s A-list but by 1967 his star was on the wane even if he still had his pick of cooler than cool tough guys in Nikkatsu’s trademark action B-movies. Mixing western and film noir, A Colt is My Passport makes a virtue of Japan’s fast moving development, heartily embracing the convenience of a society built around the idea of disposability whilst accepting the need to keep one step ahead of the rubbish truck else it swallow you whole.

Kamimura (Joe Shishido) and his buddy Shiozaki (Jerry Fujio) are on course to knock off a gang boss’ rival and then get the hell out of Japan. Kamimura, however, is a sarcastic wiseguy and so his strange sense of humour dictates that he off the guy while the mob boss he’s working for is sitting right next to him. This doesn’t go down well, and the guys’ planned airport escape is soon off the cards leaving them to take refuge in a yakuza safe house until the whole thing blows over. Blowing over, however, is something that seems unlikely and Kamimura is soon left with the responsibility of saving both his brother-in-arms Shiozaki, and the melancholy inn girl (Chitose Kobayashi) with a heart of gold who yearns for an escape from her dead end existence but finds only inertia and disappointment.

The young protege seems surprised when Kamimura tosses the expensive looking rifle he’s just used on a job into a suitcase which he then tosses into a car which is about to be tossed into a crusher, but Kamimura advises him that if you want to make it in this business, you’d best not become too fond of your tools. Kamimura is, however, a tool himself and only too aware how disposable he might be to the hands that have made use of him. He conducts his missions with the utmost efficiency, and when something goes wrong, he deals with that too.

Efficient as he is, there is one thing that is not disposable to Kamimura and that is Shiozaki. The younger man appears not to have much to do but Kamimura keeps him around anyway with Shiozaki trailing around after him respectfully. More liability than anything else, Kamimura frequently knocks Shiozaki out to keep him out of trouble – especially as he can see Shiozaki might be tempted to leap into the fray on his behalf. Kamimura has no time for feeling, no taste for factoring attachment into his carefully constructed plans, but where Shiozaki is concerned, sentimentality wins the day.

Mina, a melancholy maid at a dockside inn, marvels at the degree of Kamimura’s devotion, wishing that she too could have the kind of friendship these men have with each other. A runaway from the sea, Mina has been trapped on the docks all her adult life. Like many a Nikkatsu heroine, love was her path to escape but an encounter with a shady gangster who continues to haunt her life put paid to that. The boats come and go but Mina stays on shore. Kamimura might be her ticket out but he wastes no time disillusioning her about his lack of interest in becoming her saviour (even if he’s not ungrateful for her assistance and also realises she’s quite an asset in his quest to ensure the survival of his ally).

Pure hardboiled, A Colt is My Passport is a crime story which rejects the femme fatal in favour of the intense relationship between its two protagonists whose friendship transcends brotherhood but never disrupts the methodical poise of the always prepared Kamimura. The minor distraction of a fly in the mud perhaps reminds him of his mortality, his smallness, the fact that he is essentially “disposable” and will one day become a mere vessel for this tiny, quite irritating creature but if he has a moment of introspection it is short lived. The world may be crunching at his heels, but Kamimura keeps moving. He has his plan, audacious as it is. He will save his buddy, and perhaps he doesn’t care too much if he survives or not, but he will not go down easy and if the world wants a bite out of him, it will have to be fast or lucky.

Original trailer (no subtitles)

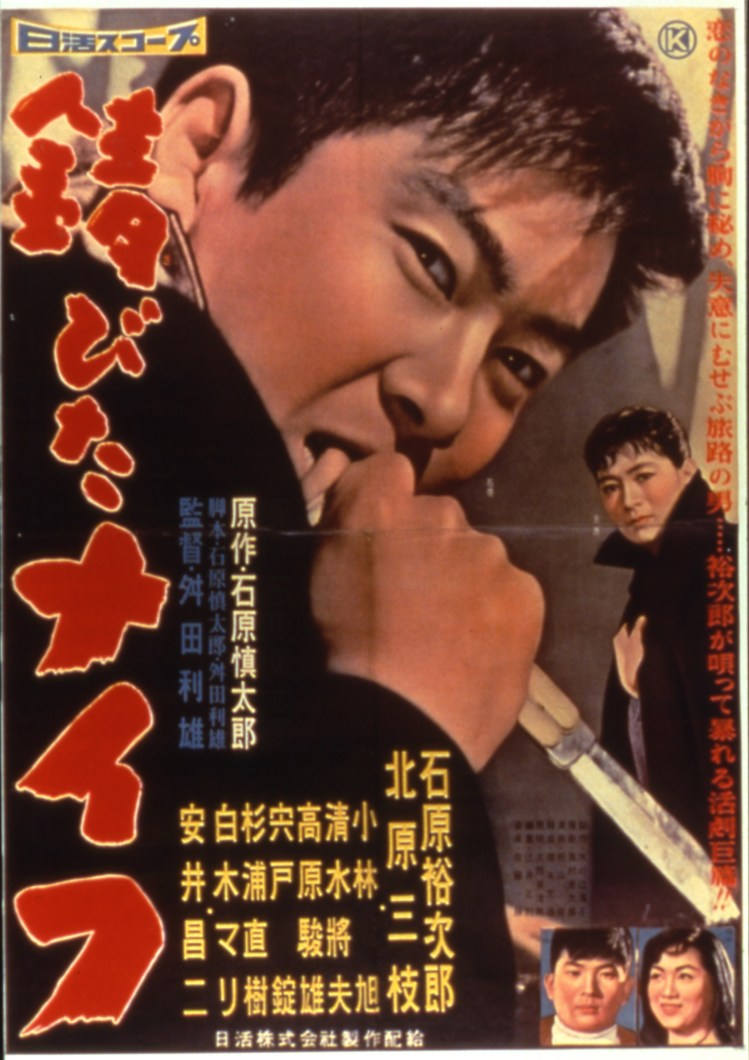

Post-war Japan was in a precarious place but by the mid-1950s, things were beginning to pick up. Unfortunately, this involved picking up a few bad habits too – namely, crime. The yakuza, as far as the movies went, were largely a pre-war affair – noble gangsters who had inherited the codes of samurai honour and were (nominally) committed to protecting the little guy. The first of many collaborations between up and coming director Toshio Masuda and the poster boy for alienated youth, Yujiro Ishihara, Rusty Knife (錆びたナイフ, Sabita Knife) shows us the other kind of movie mobster – the one that would stick for years to come. These petty thugs have no honour and are symptomatic parasites of Japan’s rapidly recovering economy, subverting the desperation of the immediate post-war era and turning it into a nihilistic struggle for total freedom from both laws and morals.

Post-war Japan was in a precarious place but by the mid-1950s, things were beginning to pick up. Unfortunately, this involved picking up a few bad habits too – namely, crime. The yakuza, as far as the movies went, were largely a pre-war affair – noble gangsters who had inherited the codes of samurai honour and were (nominally) committed to protecting the little guy. The first of many collaborations between up and coming director Toshio Masuda and the poster boy for alienated youth, Yujiro Ishihara, Rusty Knife (錆びたナイフ, Sabita Knife) shows us the other kind of movie mobster – the one that would stick for years to come. These petty thugs have no honour and are symptomatic parasites of Japan’s rapidly recovering economy, subverting the desperation of the immediate post-war era and turning it into a nihilistic struggle for total freedom from both laws and morals.

Naruse’s final silent movie coincided with his last film made at Shochiku where his down to earth artistry failed to earn him the kind of acclaim that the big hitters like Ozu found with studio head Shiro Kido. Street Without End (限りなき舗道, Kagirinaki Hodo) was a project no one wanted. Adapted from a popular newspaper serial about the life of a modern tea girl in contemporary Tokyo, it smacked a little of low rent melodrama but after being given the firm promise that after churning out this populist piece he could have free reign on his next project, Naruse accepted the compromise. Unfortunately, the agreement was not honoured and Naruse hightailed it to Photo Chemical Laboratories (later Toho) where he spent the next thirty years.

Naruse’s final silent movie coincided with his last film made at Shochiku where his down to earth artistry failed to earn him the kind of acclaim that the big hitters like Ozu found with studio head Shiro Kido. Street Without End (限りなき舗道, Kagirinaki Hodo) was a project no one wanted. Adapted from a popular newspaper serial about the life of a modern tea girl in contemporary Tokyo, it smacked a little of low rent melodrama but after being given the firm promise that after churning out this populist piece he could have free reign on his next project, Naruse accepted the compromise. Unfortunately, the agreement was not honoured and Naruse hightailed it to Photo Chemical Laboratories (later Toho) where he spent the next thirty years. Following on from

Following on from  Naruse’s critical breakthrough came in 1933 with the intriguingly titled Apart From You (君と別れて, Kimi to Wakarete) which made it into the top ten list of the prestigious film magazine Kinema Junpo at the end of the year. The themes are undoubtedly familiar and would come dominate much of Naruse’s later output as he sets out to detail the lives of two ordinary geisha and their struggles with their often unpleasant line of work, society at large, and with their own families.

Naruse’s critical breakthrough came in 1933 with the intriguingly titled Apart From You (君と別れて, Kimi to Wakarete) which made it into the top ten list of the prestigious film magazine Kinema Junpo at the end of the year. The themes are undoubtedly familiar and would come dominate much of Naruse’s later output as he sets out to detail the lives of two ordinary geisha and their struggles with their often unpleasant line of work, society at large, and with their own families. Naruse apparently directed six other films in-between

Naruse apparently directed six other films in-between  Mikio Naruse is often remembered for his female focussed stories of ordinary women trying to do they best they can in often difficult circumstances, but the earliest extant example of his work (actually his ninth film), Flunky, Work Hard (腰弁頑張れ, Koshiben Ganbare), is the sometimes comic but ultimately poignant tale of a lowly insurance salesman struggling to get ahead in depression era Japan.

Mikio Naruse is often remembered for his female focussed stories of ordinary women trying to do they best they can in often difficult circumstances, but the earliest extant example of his work (actually his ninth film), Flunky, Work Hard (腰弁頑張れ, Koshiben Ganbare), is the sometimes comic but ultimately poignant tale of a lowly insurance salesman struggling to get ahead in depression era Japan.