At the end of the previous instalment, Saizo (Raizo Ichikawa) had escaped from the fall of Osaka Castle spiriting away Sanada Yukimura (Tomisaburo Wakayama) who, in contrast to what the history books say, did not die. The pair make their way towards Shimazu, where they are also not well disposed to Ieyasu (Eitaro Ozawa), but as Saizo is informed the Tokugawa clan will never die. Knocking off Nobunaga put an end to the Oda clan, getting rid of Hideyori took the Toyotomi out of the running, but killing Ieyasu will make little difference because another retainer will swiftly take his place.

As a reminder, that’s bad for Saizo because what he wanted was the chaos of the Warring States era back to restore the ninja to their previous status. Nevertheless, at the end of the previous film he claimed to have rediscovered a human heart in his devotion to Yukimura though it may of course be simply another ruse to meet an end. In any case, Ieyasu seems to be putting his ninjas to good use and is once again waiting it out apparently aware that Yukimura is alive and well in Shimazu.

Meanwhile, times are changing. Yukimura is convinced the future of warfare lies in firearms and whoever controls Tanegashima where the weapons are made will prove victorious. They think they can gain it by figuring out how they get access to high-quality iron when trading with anyone outside of Portugal is illegal and the Portuguese don’t have any. It’s access to foreign trade which is becoming a crunch issue as Ieyasu tries to solidify his power, later giving a deathbed order to ban Christianity to stop European merchants taking over the country. Saizo travels to Tanegashima to investigate and figures out that the secret is they’re trading with China, which is pretty good blackmail material, but also encounters two sisters who turn out to be the orphaned daughters of a Tokugawa ninja with vengeance on their mind.

In a surprising turn of events, it turns out that his main adversary is Hanzo Hattori (Saburo Date) but the fact he keeps outsmarting him eventually convinces Ieyasu that the ninja have outlived their usefulness. Hanzo becomes determined to kill Saizo to restore his honour, filling the palace with various ninja traps though unlike Goemon Saizo seems to be one step ahead of them. This lengthy final sequence is played in near total silence, and ironically finds Goemon just waiting, after dispatching several of Hanzo’s men, to see if his poison dart has taken effect and Ieyasu is on his way out. Only in the end Ieyasu just laughs at him. He’s 75. Saizo’s gone to too much effort when he could have just waited it out. Ieyasu has already achieved everything he wanted to. His control over Japan is secured given he’s just been appointed chancellor. He can quite literally die happy because nothing matters to him anymore. A title card informs us that when Ieyasu did in fact die, no one really cared. The Tokugawa peace continued.

Here, once again, the Ninja too are powerless victims of fate despite their constant machinations. Yukimura tells Saizo to live and be human, advice he gives to the sisters in Tanegashima but does not take for himself staking everything on his revenge against Ieyasu which is, as he points out, pointless for Ieyasu was at death’s door anyway and his demise changed nothing. In his first of two entries in the series, Kazuo Ikehiro crafts some impressive set pieces beginning with a mist-bound underwater battle as Saizo and Yukimura make their escape by water to an epic flaming shuriken battle, though this time around the deaths are noticeably visceral. Men are drowned, stabbed, or caught on wooden spikes. Those who do not obey the ninja code are stabbed and pushed off cliffs while once again emotion is a weakness that brings about nothing more than death. Ikehiro’s frequent use of slow dissolves adds to the dreamlike feel of Saizo’s shadow existence even as the ninja themselves seem to be on the point of eclipse for what lies ahead for them in a world of peace in which there is no longer any need for stealth?

When it comes to period exploitation films of the 1970s, one name looms large – Kazuo Koike. A prolific mangaka, Koike also moved into writing screenplays for the various adaptations of his manga including the much loved Lady Snowblood and an original series in the form of Hanzo the Razor. Lone Wolf and Cub was one of his earliest successes, published between 1970 and 1976 the series spanned 28 volumes and was quickly turned into a movie franchise following the usual pattern of the time which saw six instalments released from 1972 to 1974. Martial arts specialist Tomisaburo Wakayama starred as the ill fated “Lone Wolf”, Ogami, in each of the theatrical movies as the former shogun executioner fights to clear his name and get revenge on the people who framed him for treason and murdered his wife, all with his adorable little son ensconced in a bamboo cart.

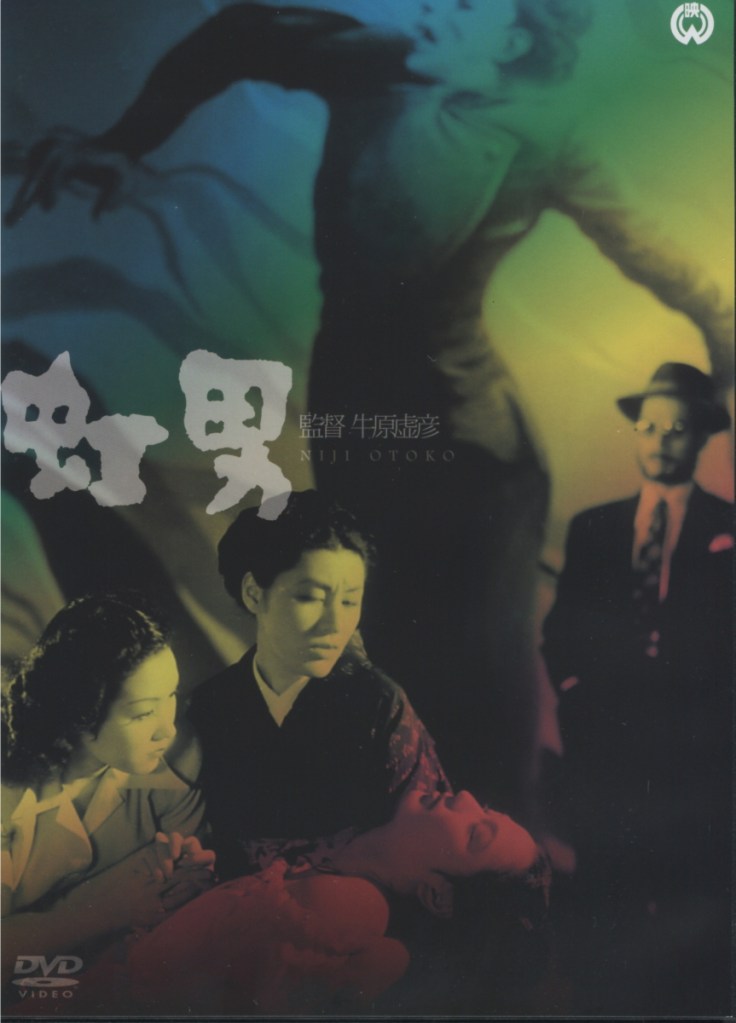

When it comes to period exploitation films of the 1970s, one name looms large – Kazuo Koike. A prolific mangaka, Koike also moved into writing screenplays for the various adaptations of his manga including the much loved Lady Snowblood and an original series in the form of Hanzo the Razor. Lone Wolf and Cub was one of his earliest successes, published between 1970 and 1976 the series spanned 28 volumes and was quickly turned into a movie franchise following the usual pattern of the time which saw six instalments released from 1972 to 1974. Martial arts specialist Tomisaburo Wakayama starred as the ill fated “Lone Wolf”, Ogami, in each of the theatrical movies as the former shogun executioner fights to clear his name and get revenge on the people who framed him for treason and murdered his wife, all with his adorable little son ensconced in a bamboo cart. “The Rainbow Man” sounds like quite a cheerful fellow, doesn’t he? How could you not be excited about a visit from such a bright and colourful chap especially as he generally turns up after the rain has ended? Daiei have once again found something happy and made it sinister in this 1949 genre effort which is sometimes called Japan’s first science fiction film though there isn’t really any sci-fi content here so much as a strange murder mystery with a weird drug at its centre.

“The Rainbow Man” sounds like quite a cheerful fellow, doesn’t he? How could you not be excited about a visit from such a bright and colourful chap especially as he generally turns up after the rain has ended? Daiei have once again found something happy and made it sinister in this 1949 genre effort which is sometimes called Japan’s first science fiction film though there isn’t really any sci-fi content here so much as a strange murder mystery with a weird drug at its centre.