Raizo Ichikawa returns as the jaded ace assassin only this time a little less serious. Set some time after the events of A Certain Killer, A Killer’s Key (ある殺し屋の鍵, Aru Koroshiya no Kagi) finds Shiozawa (Raizo Ichikawa) having left the restaurant business to teach traditional dance under the name Fujigawa while known as killer for hire Nitta in the underworld. Like the previous film, however, he thinks of himself as a justifiable good, standing up against contemporary corruption while still burdened by his traumatic past as a former tokkotai pilot.

Nitta’s troubles begin when a corruption scandal kicks off with a prominent businessman, or less generously loan shark, arrested for tax evasion. Asakura (Asao Uchida) knows too much and political kingpin Hojo (Isao Yamagata) is worried because he knows Asakura has hard evidence about a land scandal and might be persuaded to spill the beans, exposing a circle of corrupt elitists for their shady goings on. He wants Asakura knocked off on the quiet, as he heavily implies but does not explicitly state to his underling Endo (Ko Nishimura) who gets in touch with their yakuza support who in turn decide that Nitta is the only man for the job.

Petty yakuza Araki (Yoshio Kanauchi) sells the job to Nitta as a public service, pointing out how unfair it is that Asakura has been cheating on his taxes when other people have taken their own lives in shame because they weren’t able to pay. Conveniently, he doesn’t mention anything about petty vendettas or that he’s essentially being hired to silence a potential witness before he can talk so Nitta is minded to agree, for a fee of course (which, we can assume, he won’t be entering on his tax form). Unfortunately things get more complicated for everyone when the gangsters try to tie up loose ends by engineering an “accident” for Nitta which sends him on a path of revenge not only taking out the gangsters but the ones who hired them too.

Nitta’s revenge is personal in focus, but also a reflection of his antipathy to modern society as a man himself corrupted by wartime folly who should have died but has survived only to become a nihilistic contract killer. He perhaps thinks that the world is better off without men like Asakura, the dim yakuza, spineless underling Endo, and corrupt elitist Hojo but only halfheartedly. His potential love interest, Hideko (Tomomi Sato), a geisha learning traditional dance, has fallen for him, she says because she can see he’s not a cold man though continually preoccupied and there is indeed something in his aloofness which suggests that he believes in a kind of justice or at least the idea of moral good in respect of the men that died fighting for a mistaken ideal.

As Hideko puts it, Asakura made his money off the suffering of others, so perhaps it’s not surprising that he met a nasty end. She herself is a fairly cynical figure, aware as a geisha that she is in need of a sponsor and that it’s better to get the one with the most money though she too has her code and will be loyal to whoever’s paying the bills. Or so she claims, eventually willing to sell out Endo to protect Nitta but disappointed in his continued lack of reciprocation for her feelings. Echoing his parting words at the close of the first film but perhaps signalling a new conservatism he coldly tells Hideko that he doesn’t need a woman who stays with anyone who pays refusing to include her in the remainder of his mission.

Nitta is perhaps a man out of his times as a strange scene of him looking completely lost in a hip nightclub makes clear. He tries to play a circular game, stockpiling his winnings in different suitcases stored in a coin locker, but eventually finds that all his efforts have been pointless save perhaps taking out one particular strain of corruption in putting an end to Hojo’s nefarious schemes. More straightforwardly linear in execution than A Certain Killer, Killer’s Key is a less serious affair, resting squarely on an anticorruption message and easing back on the hero’s wartime trauma while allowing his needle-based hits to veer towards the ridiculous rather than the expertly planned assassination of the earlier film, but does perhaps spin an unusual crime doesn’t pay message in Nitta’s unexpected and ironic failure to secure the loot proving that sometimes not even top hit men can dodge cosmic bad luck.

Update, 13th February 2025: now available to stream via Arrow Player.

Original trailer (no subtitles)

Universal’s Monster series might have a lot to answer for in creating a cinematic canon of ambiguous “heroes” who are by turns both worthy of pity and the embodiment of somehow unnatural evil. Despite the enduring popularity of Dracula, Frankenstein (dropping his “monster” monicker and acceding to his master’s name even if not quite his identity), and even The Mummy, the Wolf Man has, appropriately enough, remained a shadowy figure relegated to a substratum of second-rate classics. Kazuhiko Yamaguchi’s Wolf Guy (ウルフガイ 燃えよ狼男, Wolf Guy: Moero Okami Otoko, AKA Wolfguy: Enraged Lycanthrope) is no exception to this rule and in any case pays little more than lip service to werewolf lore. An adaptation of a popular manga, Wolf Guy is one among dozens of disposable B-movies starring action hero Sonny Chiba which have languished in obscurity save for the attentions of dedicated superfans, but sure as a full moon its time has come again.

Universal’s Monster series might have a lot to answer for in creating a cinematic canon of ambiguous “heroes” who are by turns both worthy of pity and the embodiment of somehow unnatural evil. Despite the enduring popularity of Dracula, Frankenstein (dropping his “monster” monicker and acceding to his master’s name even if not quite his identity), and even The Mummy, the Wolf Man has, appropriately enough, remained a shadowy figure relegated to a substratum of second-rate classics. Kazuhiko Yamaguchi’s Wolf Guy (ウルフガイ 燃えよ狼男, Wolf Guy: Moero Okami Otoko, AKA Wolfguy: Enraged Lycanthrope) is no exception to this rule and in any case pays little more than lip service to werewolf lore. An adaptation of a popular manga, Wolf Guy is one among dozens of disposable B-movies starring action hero Sonny Chiba which have languished in obscurity save for the attentions of dedicated superfans, but sure as a full moon its time has come again. For one reason or another, the 1970s gave rise to a wave of disaster movies as Earthquakes devastated cities, high rise buildings caught fire, and ocean liners capsized. Japan wanted in on the action and so set about constructing its own culturally specific crisis movie. The central idea behind The Bullet Train (新幹線大爆破, Shinkansen Daibakuha) may well sound familiar as it was reappropriated for the 1994 smash hit and ongoing pop culture phenomenon Speed, but even if de Bont’s finely tuned rollercoaster was not exactly devoid of subversive political commentary The Bullet Train takes things one step further.

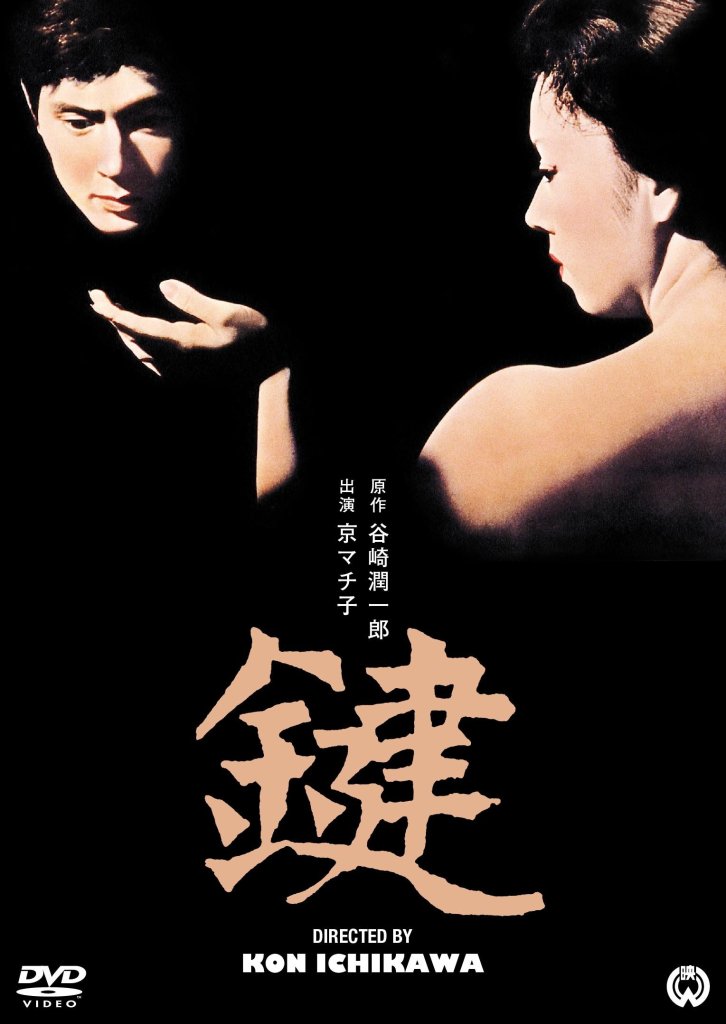

For one reason or another, the 1970s gave rise to a wave of disaster movies as Earthquakes devastated cities, high rise buildings caught fire, and ocean liners capsized. Japan wanted in on the action and so set about constructing its own culturally specific crisis movie. The central idea behind The Bullet Train (新幹線大爆破, Shinkansen Daibakuha) may well sound familiar as it was reappropriated for the 1994 smash hit and ongoing pop culture phenomenon Speed, but even if de Bont’s finely tuned rollercoaster was not exactly devoid of subversive political commentary The Bullet Train takes things one step further. Junichiro Tanizaki is widely regarded as one of the major Japanese literary figures of the twentieth century with his work frequently adapted for the cinema screen. Those most familiar with Kon Ichikawa’s art house leaning pictures such as war films The Burmese Harp or Fires on the Plain might find it quite an odd proposition but in many ways, there could be no finer match for Tanizaki’s subversive, darkly comic critiques of the baser elements of human nature than the otherwise wry director. Odd Obsession (鍵, Kagi) may be a strange title for this adaptation of Tanizaki’s well known later work The Key, but then again “odd obsessions” is good way of describing the majority of Tanizaki’s career. A tale of destructive sexuality, the odd obsession here is not so much pleasure or even dominance but a misplaced hope of sexuality as salvation, that the sheer force of stimulation arising from desire can in some way be harnessed to stave off the inevitable even if it entails a kind of personal abstinence.

Junichiro Tanizaki is widely regarded as one of the major Japanese literary figures of the twentieth century with his work frequently adapted for the cinema screen. Those most familiar with Kon Ichikawa’s art house leaning pictures such as war films The Burmese Harp or Fires on the Plain might find it quite an odd proposition but in many ways, there could be no finer match for Tanizaki’s subversive, darkly comic critiques of the baser elements of human nature than the otherwise wry director. Odd Obsession (鍵, Kagi) may be a strange title for this adaptation of Tanizaki’s well known later work The Key, but then again “odd obsessions” is good way of describing the majority of Tanizaki’s career. A tale of destructive sexuality, the odd obsession here is not so much pleasure or even dominance but a misplaced hope of sexuality as salvation, that the sheer force of stimulation arising from desire can in some way be harnessed to stave off the inevitable even if it entails a kind of personal abstinence. Ogami Itto (Tomisaburo Wakayama) and his (slightly less) young son Daigoro (Akihiro Tomikawa) are going to hell in a baby cart in this third instalment of the six film series, Lone Wolf and Cub: Baby Cart to Hades (子連れ狼 死に風に向う乳母車, Kozure Okami: Shinikazeni Mukau Ubaguruma). The former shogun executioner, framed for treason by the villainous Yagyu clan intent on assuming his position, is still on the “Demon’s Way”, seeking vengeance and the restoration of his clan’s honour with his toddler son safely ensconced within a bamboo cart which also holds its fair share of secrets. In the previous chapter,

Ogami Itto (Tomisaburo Wakayama) and his (slightly less) young son Daigoro (Akihiro Tomikawa) are going to hell in a baby cart in this third instalment of the six film series, Lone Wolf and Cub: Baby Cart to Hades (子連れ狼 死に風に向う乳母車, Kozure Okami: Shinikazeni Mukau Ubaguruma). The former shogun executioner, framed for treason by the villainous Yagyu clan intent on assuming his position, is still on the “Demon’s Way”, seeking vengeance and the restoration of his clan’s honour with his toddler son safely ensconced within a bamboo cart which also holds its fair share of secrets. In the previous chapter,  When it comes to period exploitation films of the 1970s, one name looms large – Kazuo Koike. A prolific mangaka, Koike also moved into writing screenplays for the various adaptations of his manga including the much loved Lady Snowblood and an original series in the form of Hanzo the Razor. Lone Wolf and Cub was one of his earliest successes, published between 1970 and 1976 the series spanned 28 volumes and was quickly turned into a movie franchise following the usual pattern of the time which saw six instalments released from 1972 to 1974. Martial arts specialist Tomisaburo Wakayama starred as the ill fated “Lone Wolf”, Ogami, in each of the theatrical movies as the former shogun executioner fights to clear his name and get revenge on the people who framed him for treason and murdered his wife, all with his adorable little son ensconced in a bamboo cart.

When it comes to period exploitation films of the 1970s, one name looms large – Kazuo Koike. A prolific mangaka, Koike also moved into writing screenplays for the various adaptations of his manga including the much loved Lady Snowblood and an original series in the form of Hanzo the Razor. Lone Wolf and Cub was one of his earliest successes, published between 1970 and 1976 the series spanned 28 volumes and was quickly turned into a movie franchise following the usual pattern of the time which saw six instalments released from 1972 to 1974. Martial arts specialist Tomisaburo Wakayama starred as the ill fated “Lone Wolf”, Ogami, in each of the theatrical movies as the former shogun executioner fights to clear his name and get revenge on the people who framed him for treason and murdered his wife, all with his adorable little son ensconced in a bamboo cart.

Released in 1949, The Invisible Man Appears (透明人間現る, Toumei Ningen Arawaru) is the oldest extant Japanese science fiction film. Loosely based on the classic HG Wells story The Invisible Man but taking its cues from the various Hollywood adaptations most prominently the Claude Rains version from 1933, The Invisible Man Appears also adds a hearty dose of moral guidance when it comes to scientific research.

Released in 1949, The Invisible Man Appears (透明人間現る, Toumei Ningen Arawaru) is the oldest extant Japanese science fiction film. Loosely based on the classic HG Wells story The Invisible Man but taking its cues from the various Hollywood adaptations most prominently the Claude Rains version from 1933, The Invisible Man Appears also adds a hearty dose of moral guidance when it comes to scientific research.