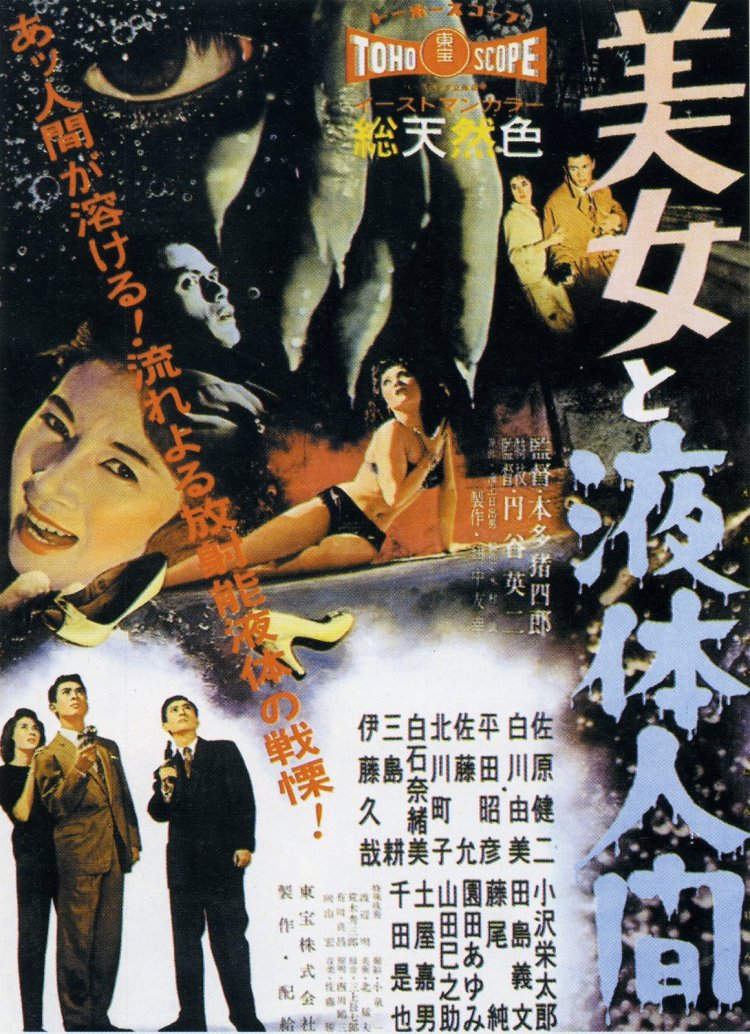

Toho produced a steady stream of science fiction movies in the ‘50s, each with some harsh words directed at irresponsible scientists whose discoveries place the whole world in peril. The H-man (美女と液体人間, Bijo to Ekitainingen), arriving in 1958, finds the genre at something of an interesting juncture but once again casts nuclear technology as the great evil, corrupting and eroding humanity with a barely understood power. Science may have conjured up the child which will one day destroy us, robbing mankind of its place as the dominant species. Still, we’ve never particularly needed science to destroy ourselves and so this particularly creepy mystery takes on a procedural bent infused with classic noir tropes and filled with the seedier elements of city life from gangsters and the drugs trade to put upon show girls with lousy boyfriends who land them in unexpected trouble.

Misaki (Hisaya Itou) is not a man who would likely have been remembered. A petty gangster on the fringes of the criminal underworld, just trying to get by in the gradually improving post-war economy, he’s one of many who might have found himself on the wrong side of a gangland battle and wound up just another name in a file. However, Misaki gets himself noticed by disappearing in the middle of a drugs heist leaving all of his clothes behind. The police immediatetely start hassling his cabaret singer girlfriend, Chikako (Yumi Shirakawa), who knows absolutely nothing but is deeply worried about what may have happened to her no good boyfriend. The police are still working on the assumption Misaki has skipped town, but a rogue professor, Masada (Kenji Sahara), thinks the disappearance may be linked to a strange nuclear incident…..

Perhaps lacking in hard science, the H-Man posits that radiation poisoning can fundamentally change the molecular structure of a living being, rendering it a kind of sentient sludge. This particular hypothesis is effectively demonstrated by doing some very unpleasant looking things to a frog but it seems humans too can be broken down into their component parts to become an all powerful liquid being. The original outbreak is thought to have occurred on a boat out at sea and the scientists still haven’t figured out why the creature has come back to Tokyo though their worst fear is that the H-man, as they’re calling him, retains some of his original memories and has tried to return “home” for whatever reason.

The sludge monster seeps and crawls, working its way in where it isn’t wanted but finally rematerialises in humanoid form to do its deadly business. Once again handled by Eiji Tsuburaya, the effects work is extraordinary as the genuinely creepy slime makes its slow motion assault before fire breaks out on water in an attempt to eradicate the flickering figures of the newly reformed H-men. The scientists think they’ve come up with a way to stop the monstrous threat, but they can’t guarantee there will never be another – think what might happen in a world covered in radioactivity! The H-man may just be another stop in human evolution.

Despite the scientists’ passionate attempts to convince them, the police remain reluctant to consider such an outlandish solution, preferring to work the gangland angle in the hopes of taking out the local drug dealers. The drug lord subplot is just that, but Misaki most definitely inhabited the seamier side of the post-war world with its seedy bars and petty crooks lurking in the shadows, pistols at the ready under their mud splattered macs. Chikako never quite becomes the generic “woman in peril” despite being directly referenced in the Japanese title, though she is eventually kidnapped by very human villains, finding herself at the mercy of violent criminality rather than rogue science. Science wants to save her, Masada has fallen in love, but their relationship is a subtle and mostly one sided one as Chikako remains preoccupied over the fate of the still missing Misaki.

Even amidst the fear and chaos, Honda finds room for a little song and dance with Chikako allowed to sing a few numbers at the bar while the other girls dance around in risqué outfits. The H-man may be another post-war anti-nuke picture from the studio which brought you Godzilla but its target is wider. Nuclear technology is not only dangerous and unpredictable, it has already changed us, corrupting body and soul. The H-men may very well be that which comes after us, but if that is the case it is we ourselves who have sown the seeds of our destruction in allowing our fiery children to break free of our control.

Original trailer (no subtitles)

Toshiaki Toyoda made an auteurst name for himself at the tail end of the ‘90s with a series of artfully composed youth dramas centring on male alienation and cultural displacement. Attempting to move beyond the world of adolescent rage by embracing Japan’s most representative genre, the family drama, in the literary adaptation

Toshiaki Toyoda made an auteurst name for himself at the tail end of the ‘90s with a series of artfully composed youth dramas centring on male alienation and cultural displacement. Attempting to move beyond the world of adolescent rage by embracing Japan’s most representative genre, the family drama, in the literary adaptation  Japan was a strange place in the early ‘90s. The bubble burst and everything changed leaving nothing but confusion and uncertainty in its place. Tokyo, like many cities, however, also had a fairly active indie music scene in part driven by the stringency of the times and representing the last vestiges of an underground art world about to be eclipsed by the resurgence of studio driven idol pop. Bandage (Bandage バンデイジ) is the story of one ordinary girl and her journey of self discovery among the struggling artists and the corporate suits desperate to exploit them. One of the many projects scripted and produced by Shunji Iwai during his lengthy break from the director’s chair, Bandage is also the only film to date directed by well known musician and Iwai collaborator Takeshi Kobayashi who evidently draws inspiration from his mentor but adds his own particular touches to the material.

Japan was a strange place in the early ‘90s. The bubble burst and everything changed leaving nothing but confusion and uncertainty in its place. Tokyo, like many cities, however, also had a fairly active indie music scene in part driven by the stringency of the times and representing the last vestiges of an underground art world about to be eclipsed by the resurgence of studio driven idol pop. Bandage (Bandage バンデイジ) is the story of one ordinary girl and her journey of self discovery among the struggling artists and the corporate suits desperate to exploit them. One of the many projects scripted and produced by Shunji Iwai during his lengthy break from the director’s chair, Bandage is also the only film to date directed by well known musician and Iwai collaborator Takeshi Kobayashi who evidently draws inspiration from his mentor but adds his own particular touches to the material. There are two kinds of people in the world, those who swing and those who…don’t – a metaphor which works just as well for baseball and, by implication, facing life’s challenges as it does for music. Shinobu Yaguchi returns after 2001’s

There are two kinds of people in the world, those who swing and those who…don’t – a metaphor which works just as well for baseball and, by implication, facing life’s challenges as it does for music. Shinobu Yaguchi returns after 2001’s  The rate of social change in the second half of the twentieth century was extreme throughout much of the world, but given that Japan had only emerged from centuries of isolation a hundred years before it’s almost as if they were riding their own bullet train into the future. Norihiro Koizumi’s Flowers (フラワーズ) attempts to chart these momentous times through examining the lives of three generations of women, from 1936 to 2009, or through Showa to Heisei, as the choices and responsibilities open to each of them grow and change with new freedoms offered in the post-war world. Or, at least, up to a point.

The rate of social change in the second half of the twentieth century was extreme throughout much of the world, but given that Japan had only emerged from centuries of isolation a hundred years before it’s almost as if they were riding their own bullet train into the future. Norihiro Koizumi’s Flowers (フラワーズ) attempts to chart these momentous times through examining the lives of three generations of women, from 1936 to 2009, or through Showa to Heisei, as the choices and responsibilities open to each of them grow and change with new freedoms offered in the post-war world. Or, at least, up to a point.

They say the way to a man’s heart is through his stomach, but for some guys you’ll have to do a whole lot of baking. Based on the popular manga which was also recently adapted into a hit anime (as is the current trend) My Love Story!! (俺物語!!, Ore Monogatari!!) is the classic tale of innocent young love between a pretty young girl and her strapping suitor only both of them are too reticent and have too many issues to be able to come round to the idea that their feelings may actually be requited after all. This is going to be a long courtship but faint heart never won fair maiden.

They say the way to a man’s heart is through his stomach, but for some guys you’ll have to do a whole lot of baking. Based on the popular manga which was also recently adapted into a hit anime (as is the current trend) My Love Story!! (俺物語!!, Ore Monogatari!!) is the classic tale of innocent young love between a pretty young girl and her strapping suitor only both of them are too reticent and have too many issues to be able to come round to the idea that their feelings may actually be requited after all. This is going to be a long courtship but faint heart never won fair maiden. In this brand new, post truth world where spin rules all, it’s important to look on the bright side and recognise the enormous positive power of the lie. 2015’s April Fools (エイプリルフールズ) is suddenly seeming just as prophetic as the machinations of the weird old woman buried at its centre seeing as its central message is “who cares about the truth so long as everyone (pretends) to be happy in the end?”. A dangerous message to be sure though perhaps there is something to be said about forgiving those who’ve misled you after understanding their reasoning. Or, then again, maybe not.

In this brand new, post truth world where spin rules all, it’s important to look on the bright side and recognise the enormous positive power of the lie. 2015’s April Fools (エイプリルフールズ) is suddenly seeming just as prophetic as the machinations of the weird old woman buried at its centre seeing as its central message is “who cares about the truth so long as everyone (pretends) to be happy in the end?”. A dangerous message to be sure though perhaps there is something to be said about forgiving those who’ve misled you after understanding their reasoning. Or, then again, maybe not. There are few things in life which cannot at least be improved by a full and frank apology. Sometimes that apology will need to go beyond a simple, if heart felt, “I’m Sorry” to truly make amends but as long as there’s a genuine desire to make things right, it can be done. Some people do, however, need help in navigating this complex series of culturally defined rituals which is where the enterprising hero of Nobuo Mizuta’s The Apology King (謝罪の王様, Shazai no Ousama), Ryoro Kurojima (Sadao Abe), comes in. As head of the Tokyo Apology Centre, Kurojima is on hand to save the needy who find themselves requiring extrication from all kinds of sticky situations such as accidentally getting sold into prostitution by the yakuza or causing small diplomatic incidents with a tiny yet very angry foreign country.

There are few things in life which cannot at least be improved by a full and frank apology. Sometimes that apology will need to go beyond a simple, if heart felt, “I’m Sorry” to truly make amends but as long as there’s a genuine desire to make things right, it can be done. Some people do, however, need help in navigating this complex series of culturally defined rituals which is where the enterprising hero of Nobuo Mizuta’s The Apology King (謝罪の王様, Shazai no Ousama), Ryoro Kurojima (Sadao Abe), comes in. As head of the Tokyo Apology Centre, Kurojima is on hand to save the needy who find themselves requiring extrication from all kinds of sticky situations such as accidentally getting sold into prostitution by the yakuza or causing small diplomatic incidents with a tiny yet very angry foreign country. Coming in at the end of the “pure love” boom, Nobuhiro Doi’s second feature, Tears for You (涙そうそう, Nada So So) is presumably named to tie in with his smash hit debut

Coming in at the end of the “pure love” boom, Nobuhiro Doi’s second feature, Tears for You (涙そうそう, Nada So So) is presumably named to tie in with his smash hit debut

Japan has never quite got the zombie movie. That’s not to say they haven’t tried, from the arty Miss Zombie to the splatter leaning exploitation fare of Helldriver, zombies have never been far from the scene even if they looked and behaved a littler differently than their American cousins. Shinsuke Sato’s adaptation of Kengo Hanazawa’s manga I Am a Hero (アイアムアヒーロー) is unapologetically married to the Romero universe even if filtered through 28 Days Later and, perhaps more importantly, Shaun of the Dead. These “ZQN” jerk and scuttle like the monsters you always feared were in the darkness, but as much as the undead threat lingers with outstretched hands of dread, Sato mines the situation for all the humour on offer creating that rarest of beasts – a horror comedy that’s both scary and funny but crucially also weighty enough to prove emotionally effective.

Japan has never quite got the zombie movie. That’s not to say they haven’t tried, from the arty Miss Zombie to the splatter leaning exploitation fare of Helldriver, zombies have never been far from the scene even if they looked and behaved a littler differently than their American cousins. Shinsuke Sato’s adaptation of Kengo Hanazawa’s manga I Am a Hero (アイアムアヒーロー) is unapologetically married to the Romero universe even if filtered through 28 Days Later and, perhaps more importantly, Shaun of the Dead. These “ZQN” jerk and scuttle like the monsters you always feared were in the darkness, but as much as the undead threat lingers with outstretched hands of dread, Sato mines the situation for all the humour on offer creating that rarest of beasts – a horror comedy that’s both scary and funny but crucially also weighty enough to prove emotionally effective.