Takahiro Miki has made a name for himself as a purveyor of sad romances. Often his protagonists are divided by conflicting timelines, social taboos, or some other fantastical circumstance, though Drawing Closer (余命一年の僕が、余命半年の君と出会った話。, Yomei Ichinen no Boku ga, Yomei Hantoshi no Kimi to Deatta Hanashi) quite clearly harks back to the jun-ai or “pure love” boom in its focus on young love and terminal illness. Based on the novel by Ao Morita, the film nevertheless succumbs to some of genres most problematic tendencies as the heroine essentially becomes little more than a means for the hero’s path towards finding purpose in life.

17-year-old Akito (Ren Nagase) is told that he has a tumour on his heart and only a year at most to live. Though he begins to feel as if his life is pointless, he finds new strength after running into Haruna (Natsuki Deguchi) who has only six months yet to him seems full of life. Later, Haruna says he was actually wrong and she felt completely hopeless too so actually she really wanted to die right away rather than pointlessly hang round for another six months with nothing to do and no one to talk to. But in any case, Akito decides that he’s going to make his remaining life’s purpose making Haruna happy which admittedly he does actually do by visiting her every day and bringing flowers once a week.

But outside of that, we never really hear that much from Haruna other than when she’s telling Akito something inspirational and he seems to more or less fill in the blanks on his own. Thus he makes what could have been a fairly rash and disastrous decision to bring a former friend, Ayaka (Mayuu Yokota), with whom Haruna had fallen out after the middle-school graduation ceremony that she was unable to go to because of her illness. Luckily he had correctly deduced that Haruna pushed her friend away because she thought their friendship was holding her back and Ayaka should be free to embrace her high school life making new friends who can do all the regular teenage things like going to karaoke or hanging out at the mall. Akito is doing something similar by not telling his other friends that he’s ill while also keeping it from Haruna in the hope that they can just be normal teens without the baggage of their illnesses.

The film never shies away from the isolating qualities of what it’s like to live with a serious health condition. Both teens just want to be treated normally while others often pull away from them or are overly solicitous after finding out that they’re ill but at the same time, it’s all life lessons for Akito rather a genuine expression of Haruna’s feelings. We only experience them as he experiences them and so really she’s denied any opportunity to express herself authentically. Rather tritely, it’s she who teaches Akito how to live again in urging him that he should hang in there and continue to pursue his artistic dreams on behalf of them both. Meanwhile, she encourages him to pursue a romantic relationship with Ayaka, in that way ensuring that neither of them will be lonely when she’s gone and pushing them towards enjoying life to its fullest.

Nevertheless, due to its unbalanced quality and general earnestness the film never really achieves the kind of emotional impact that it’s aiming for nor the sense of poignancy familiar from Miki’s other work. Perhaps taking its cues from similarly themed television drama, the production values are on the lower side and Miki’s visual flair is largely absent though this perhaps helps to express a sense of hopelessness only broken by beautiful colours of Haruna’s artwork. Haruna had used drawing as means of escaping from the reality of her condition, but in the end even this becomes about Akito with her mother declaring that in the end she drew for him rather than for herself. Even so, there is something uplifting in Akito’s rediscovery of art as a purpose for life that convinces him that his remaining time isn’t meaningless while also allowing him to discover the desire to live even if his time is running out.

Trailer (English subtitles)

The “jun-ai” boom might have been well and truly over by the time Takahiro Miki’s Girl in the Sunny Place (陽だまりの彼女, Hidamari no Kanojo) hit the screen, but tales of true love doomed are unlikely to go out of fashion any time soon. Based on a novel by Osamu Koshigaya, Girl in the Sunny Place is another genial romance in which teenage friends are separated, find each other again, become happy and then have that happiness threatened, but it’s also one that hinges on a strange magical realism born of the affinity between humans and cats.

The “jun-ai” boom might have been well and truly over by the time Takahiro Miki’s Girl in the Sunny Place (陽だまりの彼女, Hidamari no Kanojo) hit the screen, but tales of true love doomed are unlikely to go out of fashion any time soon. Based on a novel by Osamu Koshigaya, Girl in the Sunny Place is another genial romance in which teenage friends are separated, find each other again, become happy and then have that happiness threatened, but it’s also one that hinges on a strange magical realism born of the affinity between humans and cats. There are few things in life which cannot at least be improved by a full and frank apology. Sometimes that apology will need to go beyond a simple, if heart felt, “I’m Sorry” to truly make amends but as long as there’s a genuine desire to make things right, it can be done. Some people do, however, need help in navigating this complex series of culturally defined rituals which is where the enterprising hero of Nobuo Mizuta’s The Apology King (謝罪の王様, Shazai no Ousama), Ryoro Kurojima (Sadao Abe), comes in. As head of the Tokyo Apology Centre, Kurojima is on hand to save the needy who find themselves requiring extrication from all kinds of sticky situations such as accidentally getting sold into prostitution by the yakuza or causing small diplomatic incidents with a tiny yet very angry foreign country.

There are few things in life which cannot at least be improved by a full and frank apology. Sometimes that apology will need to go beyond a simple, if heart felt, “I’m Sorry” to truly make amends but as long as there’s a genuine desire to make things right, it can be done. Some people do, however, need help in navigating this complex series of culturally defined rituals which is where the enterprising hero of Nobuo Mizuta’s The Apology King (謝罪の王様, Shazai no Ousama), Ryoro Kurojima (Sadao Abe), comes in. As head of the Tokyo Apology Centre, Kurojima is on hand to save the needy who find themselves requiring extrication from all kinds of sticky situations such as accidentally getting sold into prostitution by the yakuza or causing small diplomatic incidents with a tiny yet very angry foreign country.

“Being naked in front of people is embarrassing” says the drunken mother of a recently deceased major character in a bizarre yet pivotal scene towards the end of Shunji Iwai’s aptly titled A Bride for Rip Van Winkle (リップヴァンウィンクルの花嫁, Rip Van Winkle no Hanayome) in which the director himself wakes up from an extended cinematic slumber to discover that much is changed. This sequence, in a sense, makes plain one of the film’s essential themes – truth, and the appearance of truth, as mediated by human connection. The film’s timid heroine, Nanami (Haru Kuroki), bares all of herself online, recording each ugly thought and despairing notion before an audience of anonymous strangers, yet can barely look even those she knows well in the eye. Though Namami’s fear and insecurity are painfully obvious to all, not least to herself, she’s not alone in her fear of emotional nakedness as she discovers throughout her strange odyssey in which nothing is quite as it seems.

“Being naked in front of people is embarrassing” says the drunken mother of a recently deceased major character in a bizarre yet pivotal scene towards the end of Shunji Iwai’s aptly titled A Bride for Rip Van Winkle (リップヴァンウィンクルの花嫁, Rip Van Winkle no Hanayome) in which the director himself wakes up from an extended cinematic slumber to discover that much is changed. This sequence, in a sense, makes plain one of the film’s essential themes – truth, and the appearance of truth, as mediated by human connection. The film’s timid heroine, Nanami (Haru Kuroki), bares all of herself online, recording each ugly thought and despairing notion before an audience of anonymous strangers, yet can barely look even those she knows well in the eye. Though Namami’s fear and insecurity are painfully obvious to all, not least to herself, she’s not alone in her fear of emotional nakedness as she discovers throughout her strange odyssey in which nothing is quite as it seems. Back in 2008 as the financial crisis took hold, a left leaning early Showa novel from Takiji Kobayashi, Kanikosen (蟹工船), became a surprise best seller following an advertising campaign which linked the struggles of its historical proletarian workers with the put upon working classes of the day. The book had previously been adapted for the screen in 1953 in a version directed by So Yamamura but bolstered by its unexpected resurgence, another adaptation directed by SABU arrived in 2009.

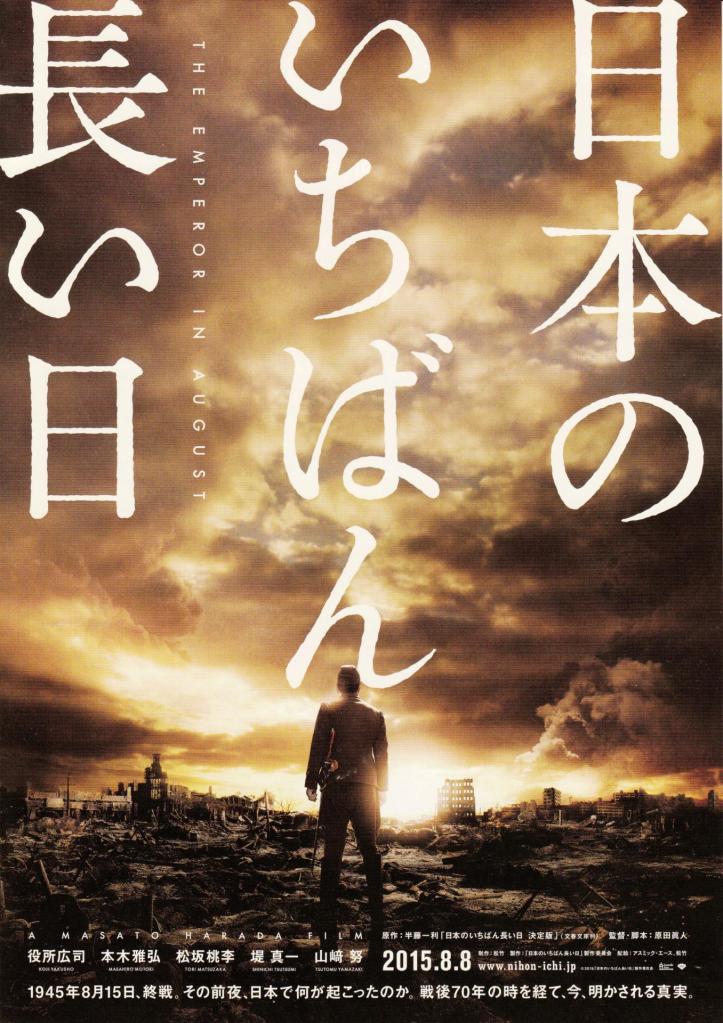

Back in 2008 as the financial crisis took hold, a left leaning early Showa novel from Takiji Kobayashi, Kanikosen (蟹工船), became a surprise best seller following an advertising campaign which linked the struggles of its historical proletarian workers with the put upon working classes of the day. The book had previously been adapted for the screen in 1953 in a version directed by So Yamamura but bolstered by its unexpected resurgence, another adaptation directed by SABU arrived in 2009. How exactly do you lose a war? It’s not as if you can simply telephone your opponents and say “so sorry, I’m a little busy today so perhaps we could agree not to kill each other for bit? Talk later, tata.” The Emperor in August examines the last few days in the summer of 1945 as Japan attempts to convince itself to end the conflict. Previously recounted by Kihachi Okamoto in 1967 under the title Japan’s Longest Day, The Emperor in August (日本のいちばん長い日, Nihon no Ichiban Nagai Hi) proves that stately events are not always as gracefully carried off as they may appear on the surface.

How exactly do you lose a war? It’s not as if you can simply telephone your opponents and say “so sorry, I’m a little busy today so perhaps we could agree not to kill each other for bit? Talk later, tata.” The Emperor in August examines the last few days in the summer of 1945 as Japan attempts to convince itself to end the conflict. Previously recounted by Kihachi Okamoto in 1967 under the title Japan’s Longest Day, The Emperor in August (日本のいちばん長い日, Nihon no Ichiban Nagai Hi) proves that stately events are not always as gracefully carried off as they may appear on the surface.