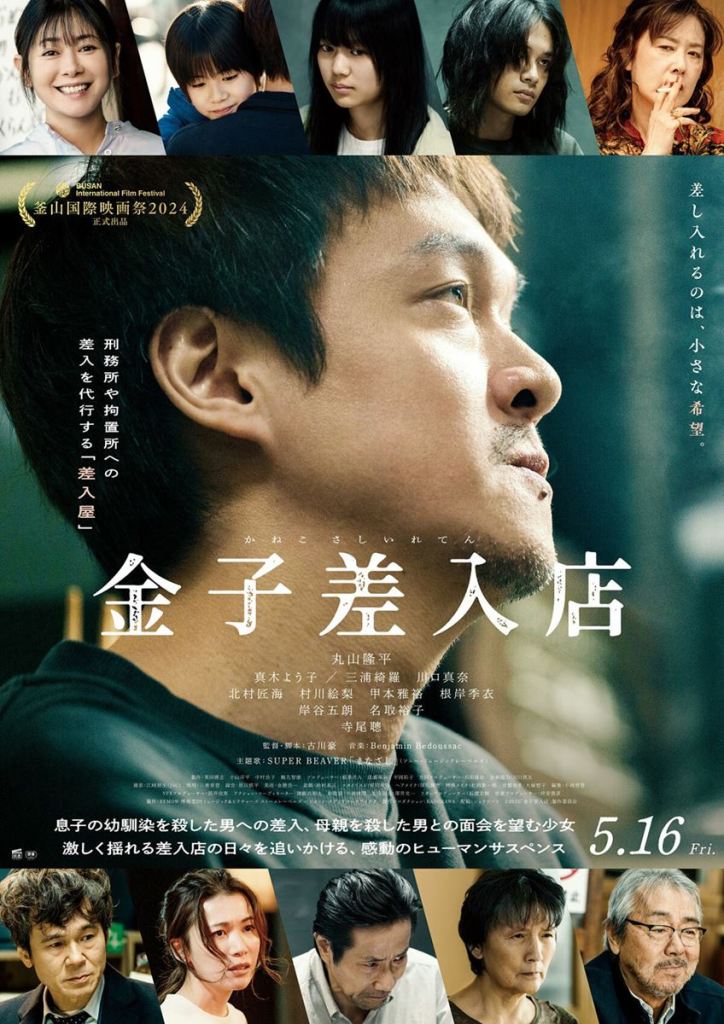

The tranquil life a man has built for himself after leaving prison is disrupted by unexpected tragedy in Go Furukawa’s social drama Kaneko’s Commissary (金子差入店, Kaneko Sashiireten). The commissary of the title refers to a service run by those like Shinji (Ryuhei Maruyama) which handles deliveries to people in prison and arranges visits by proxy. In Japan, visiting hours only take place during the day on weekdays making it difficult for visitors who work regular jobs or live far away. There’s no way to make an appointment, either. Visitors must simply show up and wait with the possibility that it might not be possible so see their friends and relatives after all given that there are only so many meeting rooms available.

The commissary service is intended to mitigate this inconvenience by acting as a bridge between the imprisoned and their families, educating them about the prison system and advising them on what can and can’t be delivered. For Shinji it seems to be a means of atonement. Sent to prison for a violent crime when his wife Miwako (Yoko Maki) was pregnant with their first child, he’d angrily lashed out her when she skipped a visit little knowing it was because she was busy giving birth. Nevertheless, several years later he’s bonded with his son and is living a happy, peaceful life. The film subtly suggests that his is partly because he’s gained a strong and supportive familial environment anchored by his formerly estranged uncle who occupies the paternal space Shinji may otherwise have been lacking. He has a complex relationship with his mother who mainly visits when he’s not home to pressure Miwako into giving her money which she fritters away on toy boys much to Shinji’s embarrassment. It’s these complex feelings towards his mother that seem to fuel his fits of rage and threaten the integrity of his new family.

But by the same token, there is external pressure too in the low-level stigma and prejudice which surrounds them simply by virtue of their proximity to crime. Though they appear to be well accepted by the community, when their son Kazuma’s friend Karin in murdered by a young man with mental health issues, it refocuses the rage of the community on them too. Someone keeps smashing the flower pots outside their home, while Miwako is ostracised by the other women in the neighbourhood and de facto sacked from her part-time job because the other employees refuse to work on the same shift as her. Kazuma starts getting bullied at school because someone found out his father had been in prison, though what his father did is obviously nothing at all to do with him.

In Japanese society, the extended family of those who’ve committed crimes is dragged into the spotlight. The mother of Karin’s killer Takashi is hounded by the media though as she says, much as she can’t understand why he did something like this, he’s a grown man and she’s not really to blame for his actions. Though we might originally feel sorry for her, especially as Takashi coldly rejects all her efforts on his behalf, she quickly becomes entitled and almost threatening. She pressures Shinji for news about her son, while he tries to avoid telling her that Takashi rejects her gifts and isn’t interested in her letters. Being forced to visit him tests the limits of his compassion as he too wonders if the man who killed Karin is really worthy of this level of care.

At the prison, he runs into another young woman who repeatedly tries to get in to see a prisoner despite the fact he keeps denying her requests. The lawyer Shinji works with has a theory about the girl, Sachiko (Mana Kawaguchi), and the yakuza she wants to wants to see. Now institutionalised, the yakuza discovered there was no place for him on the outside. His old boss was no longer around and he had no status in the underworld, so he probably committed a crime to be put away again, but at the same time maybe there was more to it than that. People save each other in unexpected ways, even it’s just with gentle acceptance and patience with a world that it is itself often lacking in the same.

Kaneko’s Commissary screens as part of this year’s Japan Foundation Touring Film Programme.

Trailer (no subtitles)