Hideo Gosha maybe best known for the “manly way” movies of his early career in which angry young men fought for honour and justice, but mostly just to to survive. Late into his career, Gosha decided to change tack for a while with a series of female orientated films either remaining within the familiar gangster genre as in Yakuza Wives, or shifting into world of the red light district as in Tokyo Bordello (吉原炎上, Yoshiwara Enjo). Presumably an attempt to get past the unfamiliarity of the Yoshiwara name, the film’s English title is perhaps a little more obviously salacious than the original Japanese which translates as Yoshiwara Conflagration and directly relates to the real life fire of 1911 in which 300 people were killed and much of the area razed to the ground. Gosha himself grew up not far from the location of the Yoshiwara as it existed in the mid-20th century where it was still a largely lower class area filled with cardsharps, yakuza, and, yes, prostitution (legal in Japan until 1958, outlawed in during the US occupation). The Yoshiwara of the late Meiji era was not so different as the women imprisoned there suffered at the hands of men, exploited by a cruelly misogynistic social system and often driven mad by internalised rage at their continued lack of agency.

Hideo Gosha maybe best known for the “manly way” movies of his early career in which angry young men fought for honour and justice, but mostly just to to survive. Late into his career, Gosha decided to change tack for a while with a series of female orientated films either remaining within the familiar gangster genre as in Yakuza Wives, or shifting into world of the red light district as in Tokyo Bordello (吉原炎上, Yoshiwara Enjo). Presumably an attempt to get past the unfamiliarity of the Yoshiwara name, the film’s English title is perhaps a little more obviously salacious than the original Japanese which translates as Yoshiwara Conflagration and directly relates to the real life fire of 1911 in which 300 people were killed and much of the area razed to the ground. Gosha himself grew up not far from the location of the Yoshiwara as it existed in the mid-20th century where it was still a largely lower class area filled with cardsharps, yakuza, and, yes, prostitution (legal in Japan until 1958, outlawed in during the US occupation). The Yoshiwara of the late Meiji era was not so different as the women imprisoned there suffered at the hands of men, exploited by a cruelly misogynistic social system and often driven mad by internalised rage at their continued lack of agency.

Opening with a voice over narration from Kyoko Kishida, the film introduces us to the heroine, 19 year old Hisano (Yuko Natori), as she is unwillingly sold to the red light district in payment for her father’s debts. After a strange orientation ceremony from the Yoshiwara police force where one “kindly” officer explains to her about the necessity of faking orgasms to save her stamina, Hisano is taken to the brothel which is now her home to begin her training. Some months later when Hisano is due to serve her first customer, she runs from him in sheer panic, leaping into a lake where a young Salvation Army campaigner, Furushima (Jinpachi Nezu), tries and fails to help her escape.

Taken back to the brothel and tied up in punishment, Hisano receives a lesson in pleasure from the current head geisha, Kiku (Rino Katase), after which she appears to settle into her work, getting promoted through various ranks until she too becomes one of the top geisha in the area. Sometime later, Furushima reappears as a wealthy young man. Regretting his inability to save her at the river and apparently having given up on his Salvation Army activities, Furushima becomes Hisano’s number one patron even though he refuses to sleep with her. Though they eventually fall in love, Hisano’s position as a geisha continues to present a barrier between the pair, forcing them apart for very different reasons.

Despite having spent a small fortune accurately recreating the main street of the Yoshiwara immediately prior to the 1911 fire, Gosha is not interested in romanticising the the pleasure quarters but depicts them as what they were – a hellish prison for enslaved women. As Hisano and Furushima later reflect, the Yoshiwara is indeed all built on lies – a place which claims to offer freedom, love, and pleasure but offers only the shadow of each of these things in an elaborate fake pageantry built on female suffering. Hisano, like many of the other women, was sold to pay a debt. Others found themselves sucked in by a continuous circle of abuse and exploitation, but none of them are free to leave until the debt, and any interest, is paid. Two of Hisako’s compatriots find other ways out of the Yoshiwara, one by her own hand, and another driven mad through illness is left alone to die like an animal coughing up blood surrounded by bright red futons in a storage cupboard.

As Kiku is quick to point out, the Yoshiwara is covered in cherry blossoms in spring but there is no place here for a tree which no longer flowers. The career of the courtesan is a short one and there are only two routes forward – become a madam or marry a wealthy client. Kiku’s plans don’t work out the way she originally envisioned, trapping her firmly within the Yoshiwara long after she had hoped to escape. Hisano is tempted by a marriage proposal from a man she truly loves but finds herself turning it down for complicated reasons. Worried that her lover does not see her as a woman, she is determined to take part in the upcoming geisha parade to force him to see her as everything she is, but her desires are never fully understood and she risks her future happiness in a futile gesture of defiance.

Defiance is the true theme of the film as each of the women fight with themselves and each other to reclaim their own freedom and individuality even whilst imprisoned and exploited by unassailable forces. Hisano, as Kiku constantly reminds her (in contrast to herself), never accepts that she is “just another whore” and therefore is able to first conquer and then escape the Yoshiwara even if it’s through a second choice compromise solution (albeit one which might bring her a degree of ordinary happiness in later life). Land of lies, the Yoshiwara promises the myth of unbridled pleasure to men who willingly make women suffer for just that purpose, further playing into Gosha’s ongoing themes of insecurity and self loathing lying at the heart of all physical or emotional violence. Though the ending voiceover is overly optimistic about the climactic fire ending centuries of female oppression as the Yoshiwara burns, Hisano, at least, may at last be free from its legacy of shame even whilst she watches the object of her desire destroyed by its very own flames.

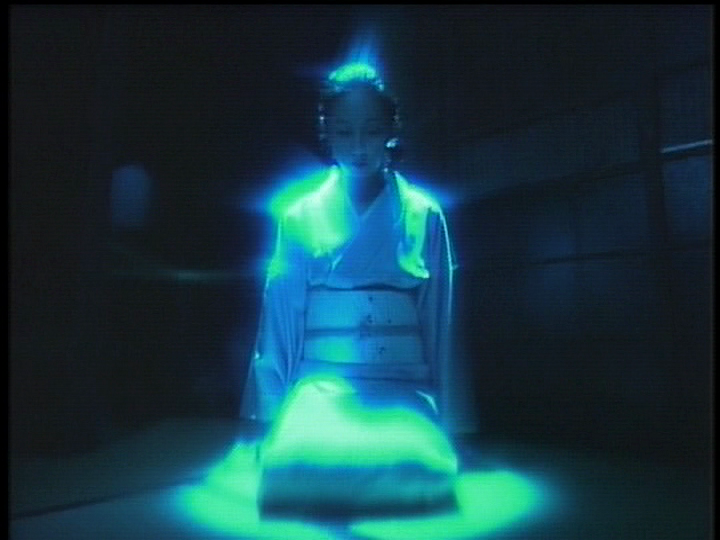

Oiran parade scene (dialogue free)

Everybody ought to have a maid, goes the old adage, but finding one you can trust can be a tall order. Kim Ki-young’s The Housemaid clearly sounds a warning call to husbands everywhere not to be tempted by the enticements of pretty young girls or conniving social climbers with designs on upending the domestic order by supplanting the legitimate wife from within her own home. The Housemaid is melodrama rewritten as horror in which a parasitical force colonises the domestic environment hell bent on taking it over through a subversion of its binding yet taboo foundation – sexual desire. Twenty years later, Suddenly in the Dark (깊은밤 갑자기, Gipeun Bam, Gapjagi) returns to the same theme but from a different angle. A once harmonious household is suddenly turned upside down following the introduction of a second female, provoking a series of crises within the already strained mind of its wife and mother.

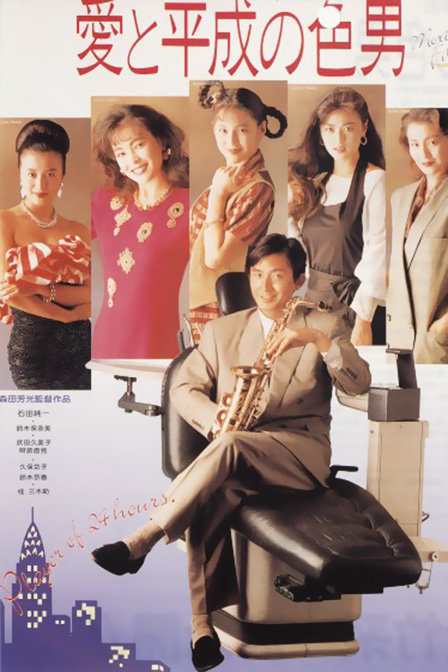

Everybody ought to have a maid, goes the old adage, but finding one you can trust can be a tall order. Kim Ki-young’s The Housemaid clearly sounds a warning call to husbands everywhere not to be tempted by the enticements of pretty young girls or conniving social climbers with designs on upending the domestic order by supplanting the legitimate wife from within her own home. The Housemaid is melodrama rewritten as horror in which a parasitical force colonises the domestic environment hell bent on taking it over through a subversion of its binding yet taboo foundation – sexual desire. Twenty years later, Suddenly in the Dark (깊은밤 갑자기, Gipeun Bam, Gapjagi) returns to the same theme but from a different angle. A once harmonious household is suddenly turned upside down following the introduction of a second female, provoking a series of crises within the already strained mind of its wife and mother. Yoshimitsu Morita is an enigma. While directing some of the most acclaimed Japanese films of the 80s including

Yoshimitsu Morita is an enigma. While directing some of the most acclaimed Japanese films of the 80s including  The ‘70s. It was a bleak time when everyone was frightened of everything and desperately needed to be reminded why everything was so terrifying by sitting in a dark room and watching a disaster unfold on-screen. Thank goodness everything is so different now! Being the extraordinarily savvy guy he was, Hiroki Kadokawa decided he could harness this wave of cold war paranoia to make his move into international cinema with the still fledgling film arm he’d added to the publishing company inherited from his father.

The ‘70s. It was a bleak time when everyone was frightened of everything and desperately needed to be reminded why everything was so terrifying by sitting in a dark room and watching a disaster unfold on-screen. Thank goodness everything is so different now! Being the extraordinarily savvy guy he was, Hiroki Kadokawa decided he could harness this wave of cold war paranoia to make his move into international cinema with the still fledgling film arm he’d added to the publishing company inherited from his father. Akio Jissoji had a wide ranging career which encompassed everything from the Buddhist trilogy of avant-garde films he made for ATG to the Ultraman TV show. Post-ATG, he found himself increasingly working in television but aside from the children’s special effects heavy TV series, Jissoji also made time for a number of small screen movies including Blue Lake Woman (青い沼の女, Aoi Numa no Onna), an adaptation of a classic story from Japan’s master of the ghost story, Kyoka Izumi. Unsettling and filled with surrealist imagery, Blue Lake Woman makes few concessions to the small screen other than in its slightly lower production values.

Akio Jissoji had a wide ranging career which encompassed everything from the Buddhist trilogy of avant-garde films he made for ATG to the Ultraman TV show. Post-ATG, he found himself increasingly working in television but aside from the children’s special effects heavy TV series, Jissoji also made time for a number of small screen movies including Blue Lake Woman (青い沼の女, Aoi Numa no Onna), an adaptation of a classic story from Japan’s master of the ghost story, Kyoka Izumi. Unsettling and filled with surrealist imagery, Blue Lake Woman makes few concessions to the small screen other than in its slightly lower production values.

Kon Ichikawa was born in 1915, just four years later than the subject of his 1989 film Actress (映画女優, Eiga Joyu) which uses the pre-directorial career of one of Japanese cinema’s most respected actresses, Kinuyo Tanaka, to explore the development of Japanese cinema itself. Tanaka was born in poverty in 1909 and worked as a jobbing film actress before being “discovered” by Hiroshi Shimizu and becoming one of Shochiku’s most bankable stars. The script is co-written by Kaneto Shindo who was fairly close to the action as an assistant under Kenji Mizoguchi at Shochiku in the ‘40s before being drafted into the war. A commemorative exercise marking the tenth anniversary of Tanaka’s death from a brain tumour in 1977, Ichikawa’s film never quite escapes from the biopic straightjacket and only gives a superficial picture of its star but seems content to revel in the nostalgia of a, by then, forgotten golden age.

Kon Ichikawa was born in 1915, just four years later than the subject of his 1989 film Actress (映画女優, Eiga Joyu) which uses the pre-directorial career of one of Japanese cinema’s most respected actresses, Kinuyo Tanaka, to explore the development of Japanese cinema itself. Tanaka was born in poverty in 1909 and worked as a jobbing film actress before being “discovered” by Hiroshi Shimizu and becoming one of Shochiku’s most bankable stars. The script is co-written by Kaneto Shindo who was fairly close to the action as an assistant under Kenji Mizoguchi at Shochiku in the ‘40s before being drafted into the war. A commemorative exercise marking the tenth anniversary of Tanaka’s death from a brain tumour in 1977, Ichikawa’s film never quite escapes from the biopic straightjacket and only gives a superficial picture of its star but seems content to revel in the nostalgia of a, by then, forgotten golden age. Back in the 1980s, you could make a film that’s actually no good at all but because of its fluffy, non-sensical cheesiness still manages to salvage something and capture the viewer’s good will in the process. In the intervening thirty years, this is a skill that seems to have been lost but at least we have films like Taylor Wong’s Behind the Yellow Line (緣份, Yuan Fen) to remind us this kind of disposable mainstream youth comedy was once possible. Starring three youngsters who would go on to become some of Hong Kong’s biggest stars over the next two decades, Behind the Yellow Line is no lost classic but is an enjoyable time capsule of its mid-80s setting.

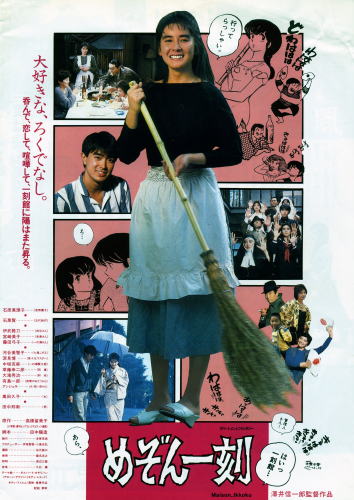

Back in the 1980s, you could make a film that’s actually no good at all but because of its fluffy, non-sensical cheesiness still manages to salvage something and capture the viewer’s good will in the process. In the intervening thirty years, this is a skill that seems to have been lost but at least we have films like Taylor Wong’s Behind the Yellow Line (緣份, Yuan Fen) to remind us this kind of disposable mainstream youth comedy was once possible. Starring three youngsters who would go on to become some of Hong Kong’s biggest stars over the next two decades, Behind the Yellow Line is no lost classic but is an enjoyable time capsule of its mid-80s setting. If you’ve always fancied a stay at that inn the

If you’ve always fancied a stay at that inn the  If you thought idol movies were all cute and quirky stories of eccentric high school girls with pretty, poppy voices then think again because Memories of You is coming for you and your faith in idols to make everything better. Directed by

If you thought idol movies were all cute and quirky stories of eccentric high school girls with pretty, poppy voices then think again because Memories of You is coming for you and your faith in idols to make everything better. Directed by