In the films of Keisuke Kinoshita, it can (generally) be assumed that the good will triumph, that those who remain true to themselves and refuse to give in to cynicism and selfishness will eventually be rewarded. This is more or less true of the convoluted Fireworks Over the Sea (海の花火, Umi no Hanabi) which takes a once successful family who have made an ill-advised entry into the fishing industry and puts them through the post-war ringer with everything from duplicitous business associates and overbearing relatives to difficult romances and unwanted arranged marriages to contend with.

The action begins in 1949 in the small harbour town of Yobuko in Southern Japan. Tarobei (Chishu Ryu) and his brother Aikawa (Takeshi Sakamoto) run a small fishing concern with two boats under the aegis of the local fishing association. The business is in big trouble and they’re convinced the captain of one of the boats has been secretly stealing part of the catch and selling it on the black market. Attempts to confront him have stalled and the brothers are at a loss, unsure how to proceed given that it will be difficult to find another captain at short notice even if they are already getting serious heat from their investors and the association.

Luckily things begin to look up when a familiar face from the past arrives in the form of Shogo (Takashi Miki) – a soldier who was briefly stationed in the town at the very end of the war during which time he fell in love with Tarobei’s eldest daughter, Mie (Michiyo Kogure). Shogo has a friend who would be perfect for taking over the boat and everything seems to be going well but the Kamiyas just can’t seem to catch a break and their attempt to construct a different economic future for themselves in the post-war world seems doomed to failure.

The Kamiyas are indeed somewhat persecuted. They have lost out precisely because of their essential goodness in which they prefer to conduct business honestly and fairly rather than give in to the selfish ways of the new society. Thus they vacillate over how to deal with the treacherous captain who has already figured out that he holds all the cards and can most likely walk all over them. They encounter the same level of oppressive intimidation when they eventually decide to fight unfair treatment from the association all the way to Tokyo only to be left sitting on a bench outside the clerk’s office for three whole days at the end of which Tarobei is taken seriously ill.

However, unlike Kinoshita’s usual heroes, Tarobei’s faith begins to waver. He is told he can get a loan from another family on the condition that their son marry his youngest daughter Miwa (Yoko Katsuragi). To begin with he laughs it off but as the situation declines he finds himself tempted even if he hates himself for the thought. He never wanted to be one of those fathers who treats his daughters like capital, but here he is. Both Miwa, who has fallen in love with the younger brother of the new captain, and her sister are in a sense at the mercy of their families, torn between personal desire familial duty. Mie, having discovered that her husband died in the war, is still trapped in post-war confusion and unsure if she returns Shogo’s feelings but in any case is afraid to pursue them when she knows the depths of despair her father finds himself in because of their precarious economic situation. Shogo is keen to help, but he is also fighting a war on two fronts seeing as his extremely strange (and somewhat overfamiliar) sister-in-law (Isuzu Yamada) is desperate to marry him off to her niece (Keiko Tsushima) in order to keep him around but also palm off her mother-in-law.

Meanwhile, a lonely geisha (Toshiko Kobayashi) who has fallen into the clutches of the corrupt captain is determined to find out what happened to someone she used to know who might be connected to Shogo and the Kamiyas and falling in desperate unrequited love with replacement captain Yabuki (Rentaro Mikuni) who is inconveniently in love with Mie. Kinoshita apparently cut production on Fireworks short in order to jet off to France which might be why his characteristically large number of interconnected subplots never coalesce. Running the gamut from melancholy existential drama to rowdy fights on boats and shootouts in the street, Kinoshita knows how to mix things up but leaves his final messages unclear as the Kamiyas willingly wave their traumatic pasts out to sea with a few extra passengers in tow still looking for new directions.

Titles and opening (no subtitles)

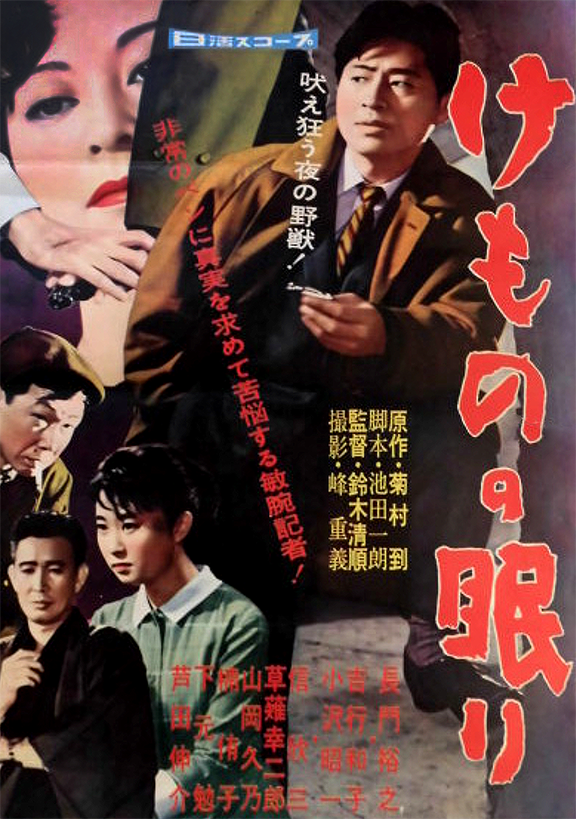

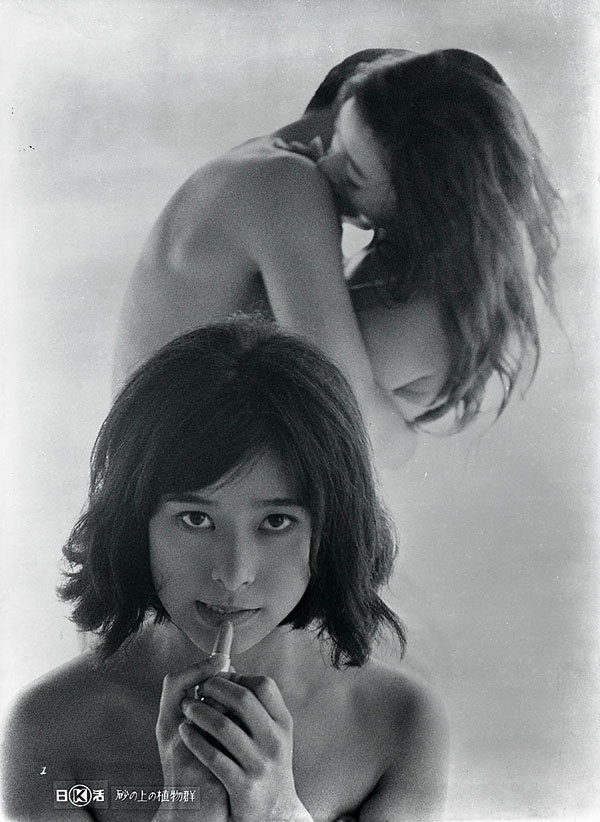

Despite being among the directors who helped to usher in what would later be called the Japanese New Wave, Ko Nakahira remains in relative obscurity with only his landmark movie of the Sun Tribe era, Crazed Fruit, widely seen abroad. Like the other directors of his generation Nakahira served his time in the studio system working on impersonal commercial projects but by 1964 which saw the release of another of his most well regarded films Only on Mondays, Nakahira had begun to give free reign to experimentation much to the studio boss’ chagrin. Flora on the Sand (砂の上の植物群, Suna no Ue no Shokubutsu-gun), adapted from the novel by Junnosuke Yoshiyuki, puts an absurd, surreal twist on the oft revisited salaryman midlife crisis as its conflicted hero muses on the legacy of his womanising father while indulging in a strange ménage à trois with two sisters, one of whom to he comes to believe he may also be related to.

Despite being among the directors who helped to usher in what would later be called the Japanese New Wave, Ko Nakahira remains in relative obscurity with only his landmark movie of the Sun Tribe era, Crazed Fruit, widely seen abroad. Like the other directors of his generation Nakahira served his time in the studio system working on impersonal commercial projects but by 1964 which saw the release of another of his most well regarded films Only on Mondays, Nakahira had begun to give free reign to experimentation much to the studio boss’ chagrin. Flora on the Sand (砂の上の植物群, Suna no Ue no Shokubutsu-gun), adapted from the novel by Junnosuke Yoshiyuki, puts an absurd, surreal twist on the oft revisited salaryman midlife crisis as its conflicted hero muses on the legacy of his womanising father while indulging in a strange ménage à trois with two sisters, one of whom to he comes to believe he may also be related to. Before Seijun Suzuki pushed his luck too far with the genre classic

Before Seijun Suzuki pushed his luck too far with the genre classic  Kon Ichikawa turns his unflinching eyes to the hypocrisy of the post-war world and its tormented youth in adapting one of Yukio Mishima’s most acclaimed works, The Temple of the Golden Pavilion. Inspired by the real life burning of the Kinkaku-ji temple in 1950 by a “disturbed” monk, Enjo (炎上, AKA Conflagration / Flame of Torment) examines the spiritual and moral disintegration of a young man obsessed with beauty but shunned by society because of a disability.

Kon Ichikawa turns his unflinching eyes to the hypocrisy of the post-war world and its tormented youth in adapting one of Yukio Mishima’s most acclaimed works, The Temple of the Golden Pavilion. Inspired by the real life burning of the Kinkaku-ji temple in 1950 by a “disturbed” monk, Enjo (炎上, AKA Conflagration / Flame of Torment) examines the spiritual and moral disintegration of a young man obsessed with beauty but shunned by society because of a disability. There’s a persistent myth that Japanese cinema avoids talking about the war directly and only addresses the war part of post-war malaise obliquely but if you look at the cinema of the early ‘50s immediately after the end of the occupation this is not the case at all. Though the strict censorship measures in place during the occupation often made referring to the war itself, the rise of militarism in the ‘30s or the American presence after the war’s end impossible, once these measures were relaxed a number of film directors who had direct experience with the conflict began to address what they felt about modern Japan. One of these directors was Masaki Kobayashi whose trilogy, The Human Condition, would come to be the best example of these films. This early effort, The Thick-Walled Room (壁あつき部屋, Kabe Atsuki Heya), scripted by Kobo Abe is one of the first attempts to tell the story of the men who’d returned from overseas bringing a troubled legacy with them.

There’s a persistent myth that Japanese cinema avoids talking about the war directly and only addresses the war part of post-war malaise obliquely but if you look at the cinema of the early ‘50s immediately after the end of the occupation this is not the case at all. Though the strict censorship measures in place during the occupation often made referring to the war itself, the rise of militarism in the ‘30s or the American presence after the war’s end impossible, once these measures were relaxed a number of film directors who had direct experience with the conflict began to address what they felt about modern Japan. One of these directors was Masaki Kobayashi whose trilogy, The Human Condition, would come to be the best example of these films. This early effort, The Thick-Walled Room (壁あつき部屋, Kabe Atsuki Heya), scripted by Kobo Abe is one of the first attempts to tell the story of the men who’d returned from overseas bringing a troubled legacy with them.