Like many directors of his generation, Kiyoshi Kurosawa began his career in “pink film” – mainstream softcore pornography produced to a strict formula. His debut had been made for Director’s Company, an independent production house which offered creative freedom to young and aspiring filmmakers. He then tried to move into the studio system by directing for Nikkatsu’s Roman Porno, but the film was rejected for not quite living up to the demands of the genre. Bumpkin Soup (ドレミファ娘の血は騒ぐ, Do-re-mi-fa-musume no Chi wa Sawagu, AKA The Excitement of the Do-Re-Mi-Fa Girl) was then purchased from Nikkatsu and released independently as his second film, earning Kurosawa something of a reputation as a contrarian. Though the film contains its fair share of nudity and strange sexual shenanigans, it is easy to see why it did not fit the Roman Porno remit thanks to its bizarrely absurdist tone and often nonsensical French New Wave-inspired post-modernism.

Like many directors of his generation, Kiyoshi Kurosawa began his career in “pink film” – mainstream softcore pornography produced to a strict formula. His debut had been made for Director’s Company, an independent production house which offered creative freedom to young and aspiring filmmakers. He then tried to move into the studio system by directing for Nikkatsu’s Roman Porno, but the film was rejected for not quite living up to the demands of the genre. Bumpkin Soup (ドレミファ娘の血は騒ぐ, Do-re-mi-fa-musume no Chi wa Sawagu, AKA The Excitement of the Do-Re-Mi-Fa Girl) was then purchased from Nikkatsu and released independently as his second film, earning Kurosawa something of a reputation as a contrarian. Though the film contains its fair share of nudity and strange sexual shenanigans, it is easy to see why it did not fit the Roman Porno remit thanks to its bizarrely absurdist tone and often nonsensical French New Wave-inspired post-modernism.

The film begins with the heroine, Akiko (Yoriko Doguchi), walking into a Tokyo university campus in search of her small-town boyfriend, Yoshioka (Kenso Kato). Yoshioka is not, however, where he said he would be – he rarely turns up to lessons and has been absent from the music club he said he had joined for some time. Determined and undaunted, Akiko continues to look for him, encountering various strange people and events including a psychology professor intent on exploring the depths of shame.

After meeting sexually obsessed female student Emi (Usagi Aso), Akiko remarks that the university campus is like a permanent festival, or perhaps an amusement park. It certainly seems to be some sort of continuous orgy as seen though the eyes of simple country girl Akiko who has, after all, only come here in search of lost love. Carrying around a walkman with a tape featuring Yoshioka’s music, she devotes herself to finding her beau but eventually sniffing him out, discovers that he’s not the man she thought he was. Truth be told, Yoshioka does not seem like much of a catch. A randy college student, he has more or less forgotten all about Akiko while he pursues just about everyone else on campus instead of going to lessons.

Latterly, Akiko comes to the realisation that she thought she was looking for an adventure leading to love, but perhaps what she really wanted was love leading to an adventure. She left the country behind, travelled to the city, transgressed borders and entered the university where she was sure she would find answers but has discovered only more questions. Akiko feels herself at odds with her new environment, unable to understand the strange grammar of the university world where people seem to talk mostly about themselves. She does, however, seem strangely taken with the befuddled professor Hirayama (Juzo Itami) whose attempts to explore the nature of shame are derailed by the “shamelessness” of the modern student.

Hirayama’s big idea is that shame is all a sham. That the custom of hiding the parts of the body we have been taught to be ashamed of is a kind of deception in itself. He hopes that in the future people will live “nakedly” without feeling the need to hide anything at all, or at least that it will be impossible to tell from the outside which parts of themselves someone might be ashamed of. In order to pursue his theories, the professor is currently engaged in experiments to provoke an “extreme shame mutation” – something which his students later undertake alone but are unable to fulfil because their subject, Emi, appears to get off on the very things they considered shameful and embarrassing which, in turn, turns them all on. So in one way a very successful experiment, but in another not. In any case, Hirayama comes to the conclusion that only Akiko, with her innocent country ways, will be capable of showing him true shame which is how she eventually becomes mixed up in his “research”.

Most obviously inspired by mid-career Godard, Kurosawa adopts a post-modern, absurdist approach satirising left-wing student politics and youthful intensity while inserting random moments of song and dance along with explicit (and often odd) sexual content that was likely still not quite enough to make it worthy of the Roman Porno name. A strange subplot pits the psychology student against a gang of mute performance artists led by a girl banging a bucket with a stick, which eventually leads to the act of nihilistic revolution which closes the film with a lullaby sung by a girl wielding a gun. What does it all mean? That shame is just a tool of social oppression, that one should make one’s own decisions without blindly following “thinkers”, that young people destroy themselves in pointless acts of revolution? Who can say, perhaps it isn’t very important but Kurosawa certainly has his fun while exploring the innocence/experience divide.

In the post-

In the post-

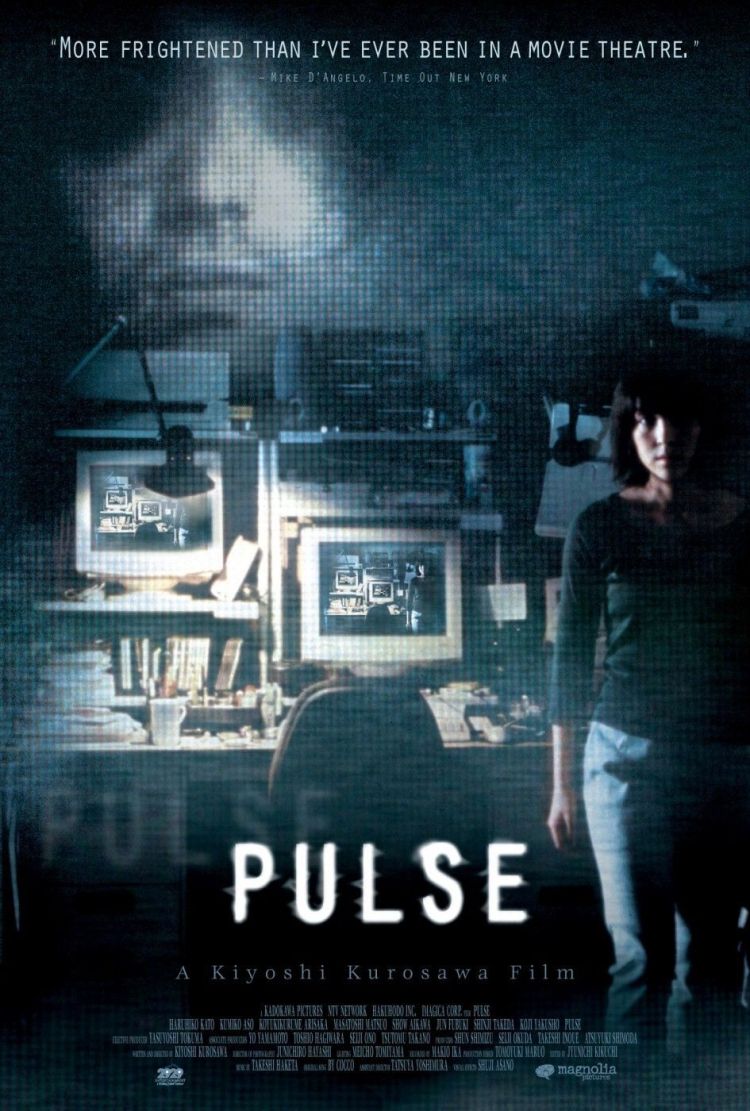

Times change and then they don’t. 2001 was a strange year, once a byword for the future it soon became the past but rather than ushering us into a new era of space exploration and a utopia born of technological advance, it brought us only new anxieties forged by ongoing political instabilities, changes in the world order, and a discomfort in those same advances we were assured would make us free. Japanese cinema, by this time, had become synonymous with horror defined by dripping wet, longhaired ghosts wreaking vengeance against an uncaring world. The genre was almost played out by the time Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s Pulse (回路, Kairo) rolled around, but rather than submitting himself to the inevitability of its demise, Kurosawa took the moribund form and pushed it as far as it could possibility go. Much like the film’s protagonists, Kurosawa determines to go as far as he can in the knowledge that standing still or turning back is consenting to your own obsolescence.

Times change and then they don’t. 2001 was a strange year, once a byword for the future it soon became the past but rather than ushering us into a new era of space exploration and a utopia born of technological advance, it brought us only new anxieties forged by ongoing political instabilities, changes in the world order, and a discomfort in those same advances we were assured would make us free. Japanese cinema, by this time, had become synonymous with horror defined by dripping wet, longhaired ghosts wreaking vengeance against an uncaring world. The genre was almost played out by the time Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s Pulse (回路, Kairo) rolled around, but rather than submitting himself to the inevitability of its demise, Kurosawa took the moribund form and pushed it as far as it could possibility go. Much like the film’s protagonists, Kurosawa determines to go as far as he can in the knowledge that standing still or turning back is consenting to your own obsolescence. Festival season is well and truly underway and in the first of two big announcements of today Cannes has confirmed its full lineup. China, HK, and Taiwan are notably absent this year but it’s otherwise a good one for Asian film with five features from Korea (inlcuding two from prolific director Hong Sang-soo) and three from Japan. Scroll down for a checklist by country:

Festival season is well and truly underway and in the first of two big announcements of today Cannes has confirmed its full lineup. China, HK, and Taiwan are notably absent this year but it’s otherwise a good one for Asian film with five features from Korea (inlcuding two from prolific director Hong Sang-soo) and three from Japan. Scroll down for a checklist by country: In the Competition section, Cannes favourite Naomi Kawase returns with her latest movie – Radiance (光, Hikari) which stars An’s Masatoshi Nagase as a photographer slowly losing his eyesight.

In the Competition section, Cannes favourite Naomi Kawase returns with her latest movie – Radiance (光, Hikari) which stars An’s Masatoshi Nagase as a photographer slowly losing his eyesight. The story of a young girl’s struggle to save her mysterious animal friend from a giant multi-national company, Okja will be streamed worldwide on Netflix from June 28.

The story of a young girl’s struggle to save her mysterious animal friend from a giant multi-national company, Okja will be streamed worldwide on Netflix from June 28.

Like many fillmakers of his generation, Kiyoshi Kurosawa began directing commercially in the 1980s working in the pink genre but it was the early ‘90s straight to video boom which provided a career breakthrough. This relatively short lived movement was built on speed where the reliability of the familiar could be harnessed to produce and market low budget genre films with a necessarily high turnover. Kurosawa made his first foray into the V-cinema world in 1994 with the unlikely comedy vehicle Yakuza Taxi (893 タクシー, 893 Taxi). Although Kurosawa had originally accepted the project in the hope of being able to direct a large scale action film, his distaste for the company’s insistence on “jingi” (the yakuza code of honour and humanity) proved something of a barrier but it did, at least, lend free rein to the director’s rather ironic sense of humour.

Like many fillmakers of his generation, Kiyoshi Kurosawa began directing commercially in the 1980s working in the pink genre but it was the early ‘90s straight to video boom which provided a career breakthrough. This relatively short lived movement was built on speed where the reliability of the familiar could be harnessed to produce and market low budget genre films with a necessarily high turnover. Kurosawa made his first foray into the V-cinema world in 1994 with the unlikely comedy vehicle Yakuza Taxi (893 タクシー, 893 Taxi). Although Kurosawa had originally accepted the project in the hope of being able to direct a large scale action film, his distaste for the company’s insistence on “jingi” (the yakuza code of honour and humanity) proved something of a barrier but it did, at least, lend free rein to the director’s rather ironic sense of humour. How well do you know your neighbours? Perhaps you have one that seems a little bit strange to you, “creepy”, even. Then again, everyone has their quirks, so you leave things at nodding at your “probably harmless” fellow suburbanites and walking away as quickly as possible. The central couple at the centre of Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s return to genre filmmaking Creepy (クリーピー 偽りの隣人, Creepy Itsuwari no Rinjin), based on the novel by Yutaka Maekawa, may have wished they’d better heeded their initial instincts when it comes to dealing with their decidedly odd new neighbours considering the extremely dark territory they’re about to move in to…

How well do you know your neighbours? Perhaps you have one that seems a little bit strange to you, “creepy”, even. Then again, everyone has their quirks, so you leave things at nodding at your “probably harmless” fellow suburbanites and walking away as quickly as possible. The central couple at the centre of Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s return to genre filmmaking Creepy (クリーピー 偽りの隣人, Creepy Itsuwari no Rinjin), based on the novel by Yutaka Maekawa, may have wished they’d better heeded their initial instincts when it comes to dealing with their decidedly odd new neighbours considering the extremely dark territory they’re about to move in to… Time is an ocean, but it ends at the shore. Kiyoshi Kurosawa neatly reverses Dylan’s poetic phrasing as his shoreline is less a place of endings but of beginnings or at least a representation of the idea that every beginning is born from the death of that which preceded it. Adapted from a novel by Kazumi Yumoto, Journey to the Shore (岸辺の旅, Kishibe no Tabi) takes its grief stricken, walking dead heroine on a long journey of the soul until she can finally put to rest a series of wandering ghosts and begin to live once again, albeit at her own tempo.

Time is an ocean, but it ends at the shore. Kiyoshi Kurosawa neatly reverses Dylan’s poetic phrasing as his shoreline is less a place of endings but of beginnings or at least a representation of the idea that every beginning is born from the death of that which preceded it. Adapted from a novel by Kazumi Yumoto, Journey to the Shore (岸辺の旅, Kishibe no Tabi) takes its grief stricken, walking dead heroine on a long journey of the soul until she can finally put to rest a series of wandering ghosts and begin to live once again, albeit at her own tempo.