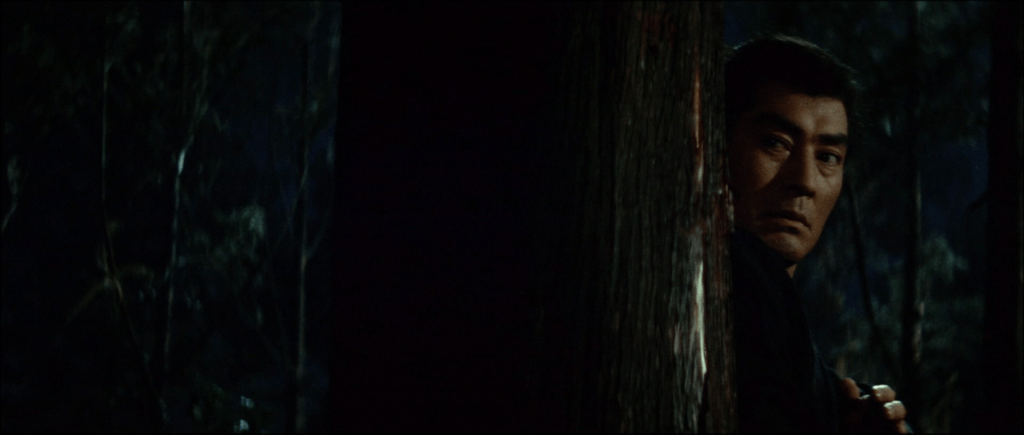

A surviving member of the Iga clan swears vengeance on Toyotomi Hideyoshi only to slowly come to the realisation that the best revenge is living well in Eiichi Kudo’s ninja drama, Castle of Owls (忍者秘帖 梟の城, Ninja Hicho: Fukuro no Shiro). Adapted from the novel by Ryotaro Shiba, the film is somewhat unusual in its positivity in allowing its hero to first reject the codes by which he was raised and then those of the prevailing times in eventually choosing love and happiness over the internecine obligation to gain vengeance against a corrupt social order.

Hoping to solidify his grip on power, Oda Nobunaga has his right-hand man Toyotomi Hideyoshi massacre the Iga clan of ninjas who are then almost entirely wiped out. Juzo (Ryutaro Otomo) and his friend Gohei (Minoru Oki) both survive, but Juzo’s entire family is brutally murdered while his sister takes her own life after being gang raped by Hideyoshi’s soldiers, using her final breath to tell her brother to avenge her. Overwhelmed by grief, Juzo is chastised by veteran ninja Jiroza (Kensaku Hara) for his show of emotion. He reminds him that a ninja should be as unbreakable as stone and that he should abandon all human sentiment. Juzo, however, insists that he may be a ninja but is also human and refuses to apologise for his feelings.

This is it seems the major conflict. Jiroza has already signalled his own heartlessness and practicality when he advised the surviving ninja to flee, for escape is less dishonourable than death. Those who refuse are welcome to surrender, and those who cannot run must be left behind to their fate. For Jiroza, all that matters is survival for both himself and his small daughter Kizaru (Chiyoko Honma) who is currently tied to his back (no mention is made of her mother, perhaps she had already passed away). Now that his family are dead, Juzo has a new mission and reason for survival insisting that what the living can do for the dead is vengeance, though in his case it is personal rather than principled for he mostly wanted revenge for his sister rather than the Iga clan as a whole or anything it represents which he otherwise seems to be at odds with.

10 years later, Oda Nobunaga has already been bumped off in an act of betrayal by one of his own men leaving Toyotomi Hideyoshi in charge and now the target for Juzo’s revenge. Around this time, Hideyoshi is planning an invasion of Korea against the advice of most of his courtiers in order to legitimise his rule through imperial ambition and military dominance. Juzo has been trying to assassinate him, and has apparently failed five times already. A surprise visit from Jiroza and his now teenage daughter involves a job opportunity promising a monetary reward should he succeed, but Juzo is wary. The merchant who hires him says he wants Hideyoshi out of the way because a war in Korea will damage his business prospects, but as Juzo points out Hideyoshi’s death will leave a power vacuum resulting in another civil war. The merchant, however, giggles childishly and remarks that domestic wars are good for business, leading Juzo to suspect he’s here on behalf of Tokugawa Ieyasu, the most likely to assume power in the event of Hideyoshi’s death.

The irony is though Juzo very definitely wants Hideyoshi dead, when someone else suggests it he becomes conflicted because he knows it will lead to another period of chaos in which even more people will die. Meanwhile, a ninja’s allegiance should belong to his client, who is always the highest bidder, so this is both a win-win situation and a mild conflict of interest. Conversely, Gohei (Minoru Oki), who was betrothed to Kizaru, has apparently betrayed the clan and taken a position as a retainer for one of Hideyoshi’s lords. He agrees to betray the Iga, inform on the plan to assassinate Hideyoshi, and even bring in Juzo in return for a 300-koku stipend and a shot of advancement under the new regime.

Now, on one level this might be understandable. Japan has emerged from a couple of hundred years of constant warfare, there’s no place for ninja in a world of peace as former Iga man Mimi (Tokue Hanasawa) remarks revealing that he’s survived the last 10 years through begging. It’s also understandable given that a ninja is expected to be duplicitous and act in self-interest. Even Juzo applaud’s Jiroza’s ninjutsu on realising that he’s teamed up with Gohei to betray him in order to take out the leader of the Koga ninjas. In essence, he’s only really done what Juzo later does but also the opposite in choosing his individual happiness through betraying those around him to throw his lot in with the person who murdered his entire clan.

Juzo meanwhile is shaken by his unexpected attraction to female ninja Kohagi (Hizuru Takachiho), a daughter of the Koga, who like him finds herself conflicted in her mission because of her growing affection for Juzo. Kohagi asks him if they really have to live on hate when they could live happily together instead, but even while conflicted Juzo can’t bring himself to let go of the idea of vengeance and is haunted by images of his friends and family dying. Even so, having decided to give up on a happy future and risk his life to kill Hideyoshi he finds that it ceases to matter. Confronting him, his hatred melts away. He begins to recognise the futility of revenge and that it would be silly to cause a war and make a merchant rich to prove a point. Gohei, meanwhile, pays a heavy price for his choices when his lord disowns him. Even when Juzo comes to rescue him from jail, he laughs that he’s caught him at last. Having escaped from the Iga life to live in the sun, he finds himself in darkness once again. Juzo, however, rides off into the sunshine with Kohagi to live in peace that’s divorced from the wider world. They choose to exile themselves from this world of darkness and duplicity, to live freely in the sunlight rather than be consumed by the internecine codes by which they were raised. Kudo films his ninja battles in near total silence with an almost balletic intensity and paints this world as one of infinite mistrust and uncertainty but equally affirms that it is possible to simply walk away and choose happiness over duty or hate.

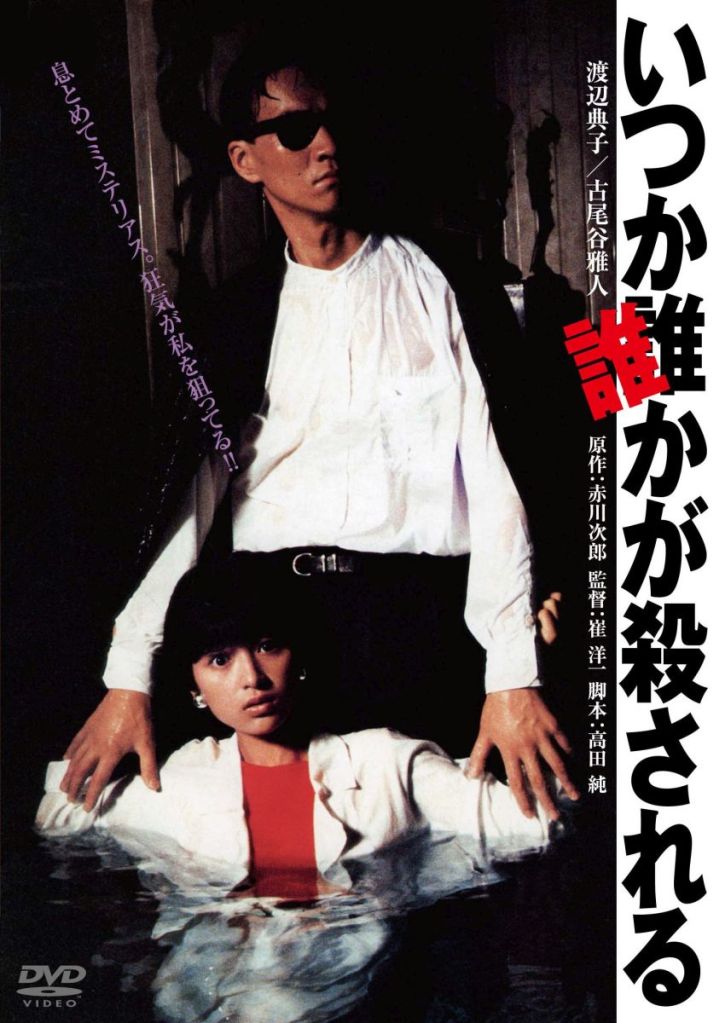

Haruki Kadokawa dominated much of mainstream 1980s cinema with his all encompassing media empire perpetuated by a constant cycle of movies, books, and songs all used to sell the other. 1984’s Someday, Someone Will be Killed (いつか誰かが殺される, Itsuka Dareka ga Korosareru) is another in this familiar pattern adapting the Kadokawa teen novel by Jiro Akagawa and starring lesser idol Noriko Watanabe in one of her rare leading performances in which she also sings the similarly titled theme song. The third film from Korean/Japanese director Yoichi Sai, Someday, Someone Will be Killed is an impressive mix of everything which makes the world Kadokawa idol movies so enticing as the heroine finds herself unexpectedly at the centre of an ongoing international conspiracy protected only by a selection of underground drop outs but faces her adversity with typical perkiness and determination safe in the knowledge that nothing really all that bad is going to happen.

Haruki Kadokawa dominated much of mainstream 1980s cinema with his all encompassing media empire perpetuated by a constant cycle of movies, books, and songs all used to sell the other. 1984’s Someday, Someone Will be Killed (いつか誰かが殺される, Itsuka Dareka ga Korosareru) is another in this familiar pattern adapting the Kadokawa teen novel by Jiro Akagawa and starring lesser idol Noriko Watanabe in one of her rare leading performances in which she also sings the similarly titled theme song. The third film from Korean/Japanese director Yoichi Sai, Someday, Someone Will be Killed is an impressive mix of everything which makes the world Kadokawa idol movies so enticing as the heroine finds herself unexpectedly at the centre of an ongoing international conspiracy protected only by a selection of underground drop outs but faces her adversity with typical perkiness and determination safe in the knowledge that nothing really all that bad is going to happen. Hideo Gosha maybe best known for the “manly way” movies of his early career in which angry young men fought for honour and justice, but mostly just to to survive. Late into his career, Gosha decided to change tack for a while with a series of female orientated films either remaining within the familiar gangster genre as in Yakuza Wives, or shifting into world of the red light district as in Tokyo Bordello (吉原炎上, Yoshiwara Enjo). Presumably an attempt to get past the unfamiliarity of the Yoshiwara name, the film’s English title is perhaps a little more obviously salacious than the original Japanese which translates as Yoshiwara Conflagration and directly relates to the real life fire of 1911 in which 300 people were killed and much of the area razed to the ground. Gosha himself grew up not far from the location of the Yoshiwara as it existed in the mid-20th century where it was still a largely lower class area filled with cardsharps, yakuza, and, yes, prostitution (legal in Japan until 1958, outlawed in during the US occupation). The Yoshiwara of the late Meiji era was not so different as the women imprisoned there suffered at the hands of men, exploited by a cruelly misogynistic social system and often driven mad by internalised rage at their continued lack of agency.

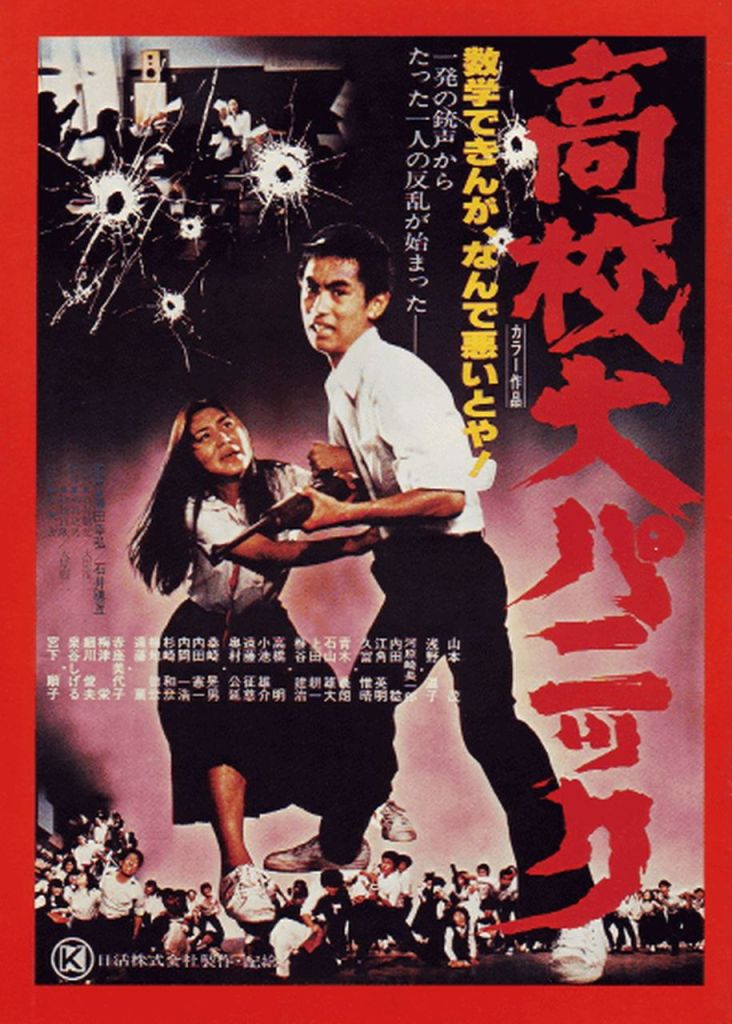

Hideo Gosha maybe best known for the “manly way” movies of his early career in which angry young men fought for honour and justice, but mostly just to to survive. Late into his career, Gosha decided to change tack for a while with a series of female orientated films either remaining within the familiar gangster genre as in Yakuza Wives, or shifting into world of the red light district as in Tokyo Bordello (吉原炎上, Yoshiwara Enjo). Presumably an attempt to get past the unfamiliarity of the Yoshiwara name, the film’s English title is perhaps a little more obviously salacious than the original Japanese which translates as Yoshiwara Conflagration and directly relates to the real life fire of 1911 in which 300 people were killed and much of the area razed to the ground. Gosha himself grew up not far from the location of the Yoshiwara as it existed in the mid-20th century where it was still a largely lower class area filled with cardsharps, yakuza, and, yes, prostitution (legal in Japan until 1958, outlawed in during the US occupation). The Yoshiwara of the late Meiji era was not so different as the women imprisoned there suffered at the hands of men, exploited by a cruelly misogynistic social system and often driven mad by internalised rage at their continued lack of agency. Sogo (now Gakyruu) Ishii was only 20 years old when Nikkatsu commissioned him to turn his smash hit 8mm short into a full scale studio picture. Perhaps that’s why they partnered him with one of their steadiest hands in Yukihiro Sawada as a co-director though the youthful punk attitude that would become Ishii’s signature is very much in evidence here despite the otherwise mainstream studio production. That said, Nikkatsu in this period was a far less sophisticated operation than it had been a decade before and, surprisingly, Panic High School (高校大パニック, Koukou Dai Panic) neatly avoids the kind of exploitative schlock that its title might suggest.

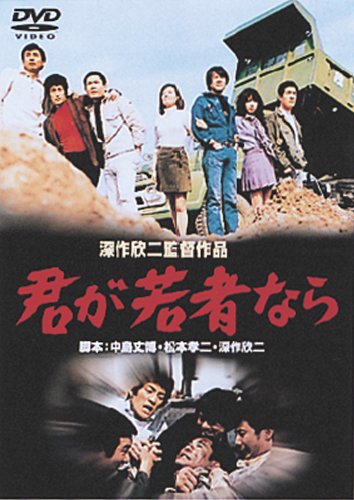

Sogo (now Gakyruu) Ishii was only 20 years old when Nikkatsu commissioned him to turn his smash hit 8mm short into a full scale studio picture. Perhaps that’s why they partnered him with one of their steadiest hands in Yukihiro Sawada as a co-director though the youthful punk attitude that would become Ishii’s signature is very much in evidence here despite the otherwise mainstream studio production. That said, Nikkatsu in this period was a far less sophisticated operation than it had been a decade before and, surprisingly, Panic High School (高校大パニック, Koukou Dai Panic) neatly avoids the kind of exploitative schlock that its title might suggest. For 1970’s If You We’re Young: Rage (君が若者なら, Kimi ga Wakamono Nara), Fukasaku returns to his most prominent theme – disaffected youth and the lack of opportunities afforded to disadvantaged youngsters during the otherwise booming post-war era. Like the more realistic gangster epics that were to come, Fukasaku laments the generation who’ve been sold an unattainable dream – come to the city, work hard, make a decent life for yourself. Only what the young men find here is overwork, exploitation and a considerably decreased likelihood of being able to achieve all they’ve been promised.

For 1970’s If You We’re Young: Rage (君が若者なら, Kimi ga Wakamono Nara), Fukasaku returns to his most prominent theme – disaffected youth and the lack of opportunities afforded to disadvantaged youngsters during the otherwise booming post-war era. Like the more realistic gangster epics that were to come, Fukasaku laments the generation who’ve been sold an unattainable dream – come to the city, work hard, make a decent life for yourself. Only what the young men find here is overwork, exploitation and a considerably decreased likelihood of being able to achieve all they’ve been promised.