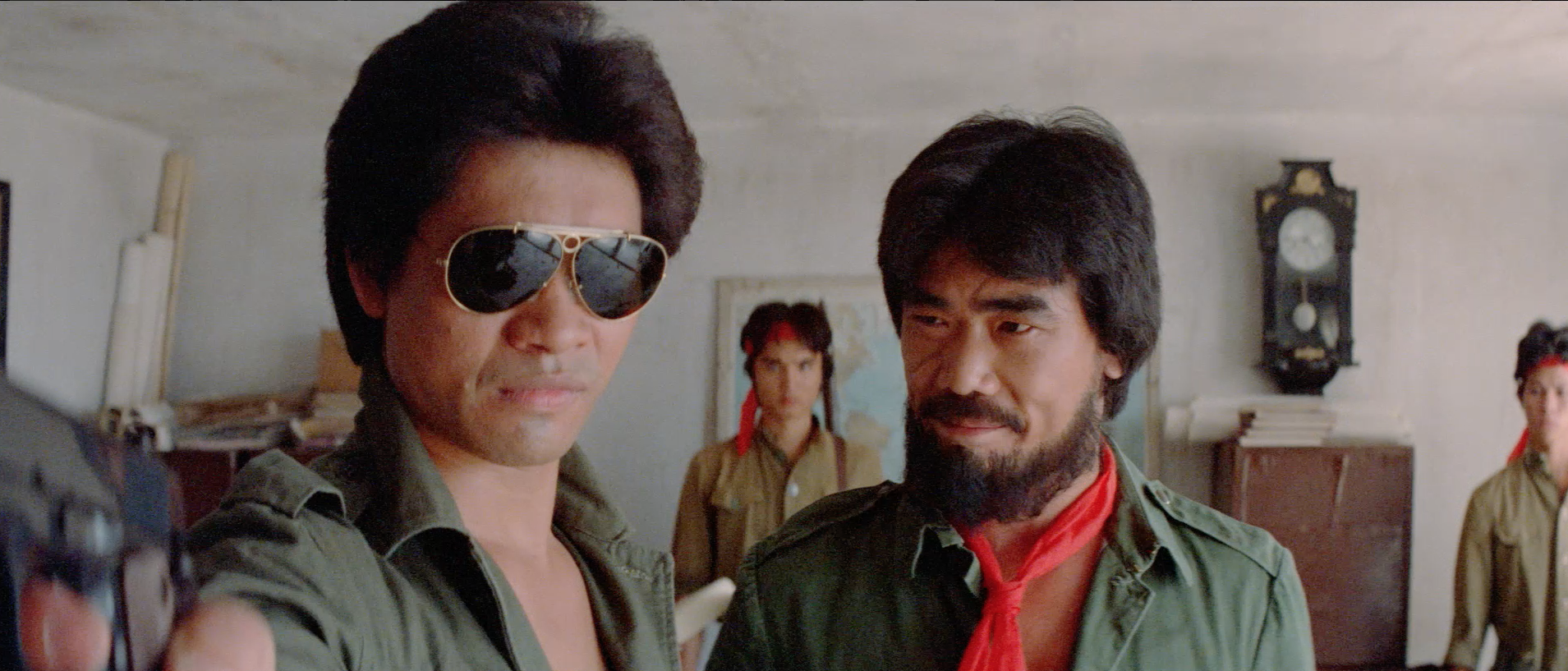

A prince in hiding develops a fondness for a bumbling jewel thief in Lau Kar-leung’s anarchic kung fu comedy, Dirty Ho (爛頭何). The English title is apparently intended as a Dirty Harry reference, though the film obviously has nothing at all to do with the Don Siegel procedural, the Chinese meaning something like “rotten head Ho”, and is in effect a homoerotic buddy movie as the various power balances begin to shift between the two men until they come to function in perfect synchronicity almost in fact as one.

The film opens, however, with a dispute over courtesans and a game of one-upmanship between prince in disguise Wang (Gordon Liu) and cocky jewel thief Ho (Wong Yue). The pair promise ever greater sums of riches in return for female company, eventually ending up in a fight interrupted when the police are called about some stolen treasure. However, at the last second, Wang says both the treasure chests are his and that he is a legitimate jewel seller from Beijing. He saves Ho from arrest, but also takes the stolen treasure chest with him, ensuring Ho will later return to take it back.

Why Wang takes a liking to him isn’t really clear, but even in his clumsy martial arts skills he seems to see something that could be polished if only he could turn him into an upright citizen. He does this partly by means of trickery, injuring Ho on the head with a poisoned sword and then promising him the antidote but only if he agrees to become his disciple and do exactly as he says. For the rest of the film, Ho wears a large black plaster on his head that slowly decreases in size as he begins to reform under Wang’s tutelage. But the power dynamic between them later shifts when Wang is injured and has to use a wheelchair with Ho now dependent on him for care and protection.

What emerges between them is strangely like a marriage while the two of them are later accosted by the “Seven Agonies” led by a very effeminate man who also causes Ho to take on a camp persona until actively rejecting it. No one is really quite as they seem, Wang actually a prince in disguise hiding out from his 13 brothers, and in particular the fourth one, who really want him dead so they can inherit the kingdom. In true martial arts fashion, Wang isn’t interested in the throne, fame, or fortune, but rather than a commitment to resisting oppression simply wants to be free to enjoy the finer things in life like art, antiques, and strong liquor.

Meanwhile, the two are also attacked by a gang of bandits faking disabilities and Wang at one point tries to pass off one of the concubines as his bodyguard to conceal the extent of his martial arts skills. Reuniting with Gordon Liu after 36th Chamber of Shaolin, Lau’s choreography has a playful, slapstick sensibility such as in the ongoing duel of swapped tankards with one of the assassins. The hand movements are fast and precise, a maze and flurry of moment culminating in the final showdown with Lo Lieh’s enemy general in which the two men are so perfectly in tune that they move almost as one.

Lau stages an increasingly surreal sequence of events, including the pair sheltering under umbrellas in the middle of a dilapidated town while targeted by assassins hired by Wang’s brother, but ends in curiously ambiguous fashion with the matter of the court unresolved despite Wang’s desire to live freely as he chooses. Of course, a prince he is but Wang is also constrained by his social status in much the same way Ho is prevented from living his authentic life because of the obligations entailed with being a potential heir to the throne. Meanwhile, it seems the king is doddery and has unwittingly created a vacuum which has pit his 14 sons against each other, destabilising the society in the process. Not wanting the job actually makes Wang an ideal candidate though, he’d have to survive all the assassination attempts first. A riot of colour and witty humour, the film boats some of Lau’s most intricate choreography performed by two actors at the top of their game who are perfectly primed to bounce of each other in a humorous back and for between the shifting sands of master and pupil.

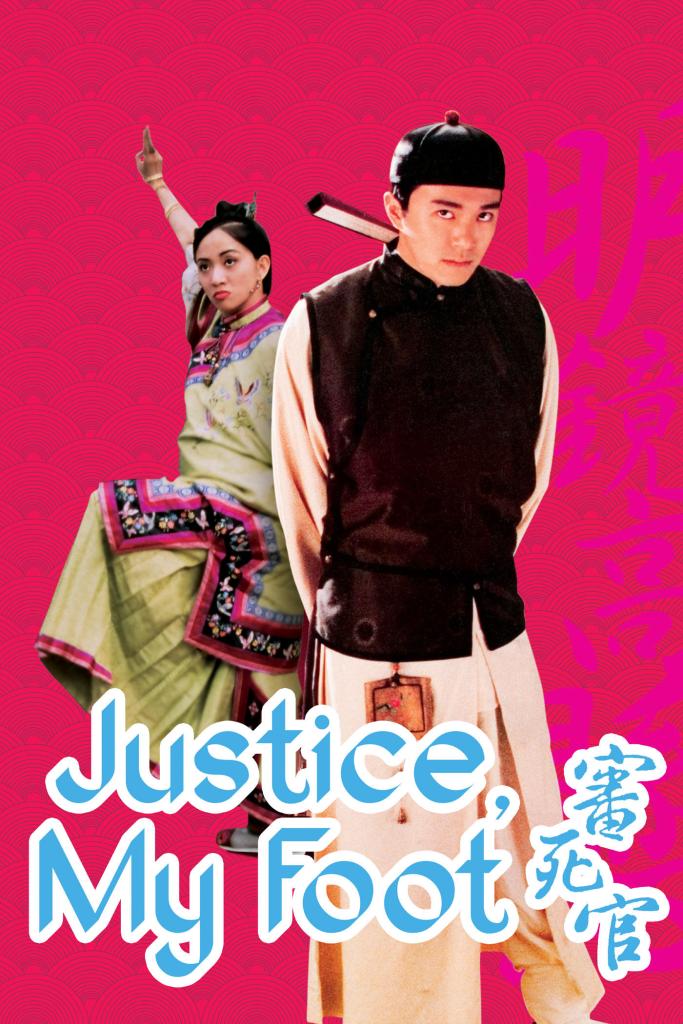

Stephen Chow has always been a force of nature but even before making his name as a director in the mid-90s, he contributed his madcap energy to some of the highest grossing movies of the era. Justice, My Foot! (審死官) is very much of the “makes no sense” comedy genre and, directed by Johnnie To for Shaw Brothers, makes great use of the collective propensity for whimsy on offer. Even if not quite managing to keep the momentum going until the closing scenes, Justice, My Foot! succeeds in delivering quick fire (often untranslatable) jokes and period martial arts action sure to keep genre fans happy.

Stephen Chow has always been a force of nature but even before making his name as a director in the mid-90s, he contributed his madcap energy to some of the highest grossing movies of the era. Justice, My Foot! (審死官) is very much of the “makes no sense” comedy genre and, directed by Johnnie To for Shaw Brothers, makes great use of the collective propensity for whimsy on offer. Even if not quite managing to keep the momentum going until the closing scenes, Justice, My Foot! succeeds in delivering quick fire (often untranslatable) jokes and period martial arts action sure to keep genre fans happy. Where oh where are the put upon citizens of martial arts movies supposed to grab a quiet cup of tea and some dim sum? Definitely not at Boss Cheng’s teahouse as all hell is about to break loose in there when it becomes the centre of a turf war in gloomy director Kuei Chih-Hung’s social minded modern day kung-fu movie The Teahouse (成記茶樓, Cheng Ji Cha Lou).

Where oh where are the put upon citizens of martial arts movies supposed to grab a quiet cup of tea and some dim sum? Definitely not at Boss Cheng’s teahouse as all hell is about to break loose in there when it becomes the centre of a turf war in gloomy director Kuei Chih-Hung’s social minded modern day kung-fu movie The Teahouse (成記茶樓, Cheng Ji Cha Lou).