There’s no statute of limitations on guilt an ageing policeman laments in Haruhiko Mimura’s adaptation of the Seicho Matsumoto mystery, Amagi Pass (天城越え, Amagi-Goe). Co-produced by Yoshitaro Nomura and co-scripted by Tai Kato, Amagi Pass arrives at the tail end of the box office dominance of the prestige whodunnit and like many of its kind hinges on events which took place during the war though in this case the effects are more psychological than literal, hinging on the implications of an age of violence and hyper masculinity coupled with sexual repression and a conservative culture.

In a voiceover which doesn’t quite open the film, the hero, Kenzo (Mikijiro Hira / Yoichi Ito), as we will later realise him to be, likens himself to that of Kawabata’s Izu Dancer though as he explains he was not a student but the 14-year-old son of a blacksmith with worn out zori on his feet as he attempted to run away from home in the summer of 1940 only to turn back half-way through. In the present day, meanwhile, an elderly detective, Tajima (Tsunehiko Watase), now with a prominent limp, slowly makes his way through the modern world towards a print shop where he orders 300 copies of the case report on the murder of an itinerant labourer in Amagi Pass in June, 1940. A wandering geisha was later charged with the crime but as Tajima explains he does not believe that she was guilty and harbours regrets over his original investigation recognising his own inexperience in overseeing his first big case.

As so often, the detective’s arrival is a call from the past, forcing Kenzo, now a middle-aged man, to reckon with the traumatic events of his youth. Earlier we had seen him in a doctor’s office where it is implied that something is poisoning him and needs to come out, his illness just as much of a reflection of his trauma as the policeman’s limp. Flashing back to 1940 we find him a young man confused, fatherless but perhaps looking for fatherly guidance from older men such as a strange pedlar he meets on the road who cheekily shows him illustrated pornography, or the wise uncle who eventually tricks him into buying dinner and then leaves. His problems are perhaps confounded by the fact that he lives in an age of hyper masculinity, the zenith of militarism in which other young men are feted with parades as they prepare to fight and die for their country in faraway lands. Yet Kenzo is only 14 in 1940 which means he will most likely be spared but also in a sense emasculated as a lonely boy remaining behind at home.

He tells the wise man who later tricks him that he’s run away to find his brother who owns a print shop in the city because he hates his provincial life as a blacksmith, but later we realise that the cause is more his difficult relationship with his widowed mother (Kazuko Yoshiyuki) whom, he has recently discovered, is carrying on an affair with his uncle (Ichiro Ogura). Returning home after his roadside betrayal he watches them together from behind a screen, a scene echoed in his voyeuristic observation of the geisha, Hana (Yuko Tanaka), with the labourer plying her trade in order to survive. Described as odd and seemingly mute, the labourer is a figure of conflicted masculinity resented by the other men on the road but also now a symbolic father and object of sexual jealously for the increasingly Oedipal Kenzo whose youthful attraction to the beautiful geisha continues to mirror his complicated relationship with his mother as she tenderly tears up her headscarf to bandage his foot, sore from his ill-fitting zori, while alternately flirting with him.

Yet his guilt towards her isn’t only in his attraction but in its role in what happened to her next even as she, we can see, protects him, their final parting glance a mix of frustrated maternity and longing that has apparently informed the rest of Kenzo’s life in ways we can never quite grasp. Amagi Pass for him is a barrier between youth and age, one which he has long since crossed while also in a sense forever trapped in the tunnel looking back over his shoulder towards Hana and the labourer now on another side of an unbreachable divide. The policeman comes like messenger from another time, incongruously wandering through a very different Japan just as the bikers in the film’s post-credit sequence speed through the pass, looking to provide closure and perhaps a healing while assuaging his own guilt but finding only accommodation with rather than a cure for the traumatic past.

Original trailer (no subtitles)

Neither Seicho Matsumoto’s original novel or the film adaptation are directly related to the well-known Sayuri Ishikawa song of the same name released three years later though the lyrics are strangely apt.

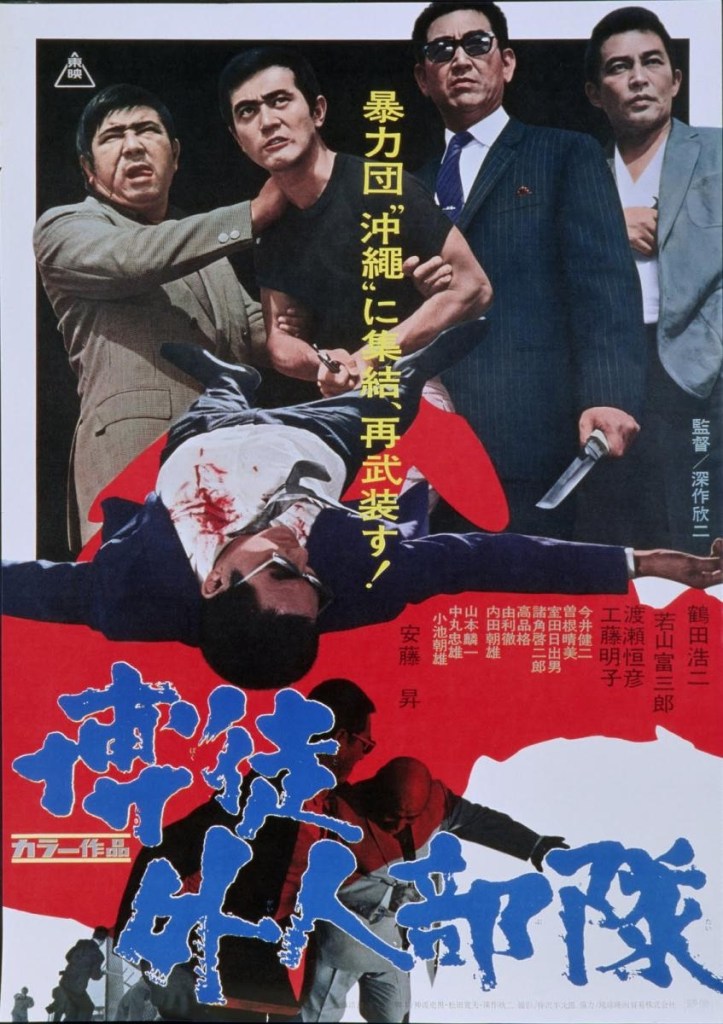

Sadao Nakajima had made his name with Toei’s particular brand of violent action movie, but by the early seventies, the classic yakuza flick was going out of fashion. Datsugoku Hiroshima Satsujinshu (脱獄広島殺人囚, AKA The Rapacious Jailbreaker) follows in the wake of seminal genre buster,

Sadao Nakajima had made his name with Toei’s particular brand of violent action movie, but by the early seventies, the classic yakuza flick was going out of fashion. Datsugoku Hiroshima Satsujinshu (脱獄広島殺人囚, AKA The Rapacious Jailbreaker) follows in the wake of seminal genre buster,  Robbing a bank is harder than it looks but if it does all go very wrong, escaping by bus is not an ideal solution. Sadao Nakajima is best known for his gritty yakuza movies but Kurutta Yaju ( 狂った野獣, Crazed Beast/Savage Beast Goes Mad) takes him in a slightly different direction with its strangely comic tale of bus hijacking, counter hijacking, inept police, and fretting mothers. If it can go wrong it will go wrong, and for a busload of people in Kyoto one sunny morning, it’s going to be a very strange day indeed.

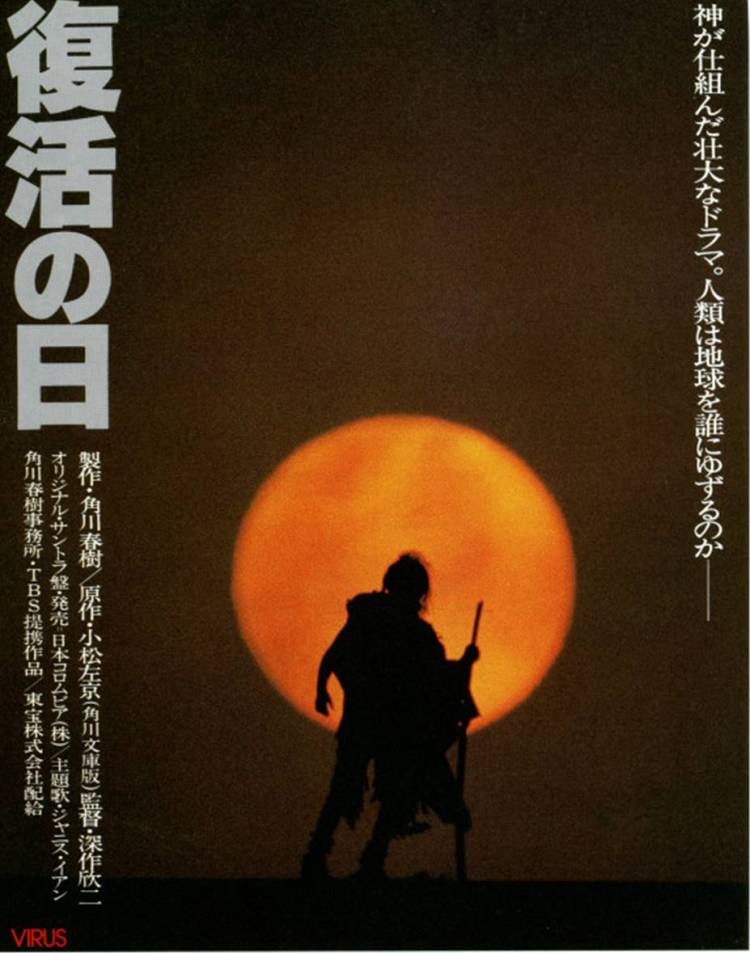

Robbing a bank is harder than it looks but if it does all go very wrong, escaping by bus is not an ideal solution. Sadao Nakajima is best known for his gritty yakuza movies but Kurutta Yaju ( 狂った野獣, Crazed Beast/Savage Beast Goes Mad) takes him in a slightly different direction with its strangely comic tale of bus hijacking, counter hijacking, inept police, and fretting mothers. If it can go wrong it will go wrong, and for a busload of people in Kyoto one sunny morning, it’s going to be a very strange day indeed. The ‘70s. It was a bleak time when everyone was frightened of everything and desperately needed to be reminded why everything was so terrifying by sitting in a dark room and watching a disaster unfold on-screen. Thank goodness everything is so different now! Being the extraordinarily savvy guy he was, Hiroki Kadokawa decided he could harness this wave of cold war paranoia to make his move into international cinema with the still fledgling film arm he’d added to the publishing company inherited from his father.

The ‘70s. It was a bleak time when everyone was frightened of everything and desperately needed to be reminded why everything was so terrifying by sitting in a dark room and watching a disaster unfold on-screen. Thank goodness everything is so different now! Being the extraordinarily savvy guy he was, Hiroki Kadokawa decided he could harness this wave of cold war paranoia to make his move into international cinema with the still fledgling film arm he’d added to the publishing company inherited from his father.