The evils of of authoritarianism are recast as family drama in Keisuke Kinoshita’s 1949 satirical comedy, Broken Drum (破れ太鼓, Yabure Daiko). Co-scripted by Masaki Kobayashi, a student of Kinoshita’s who went on to forge a long career dedicated to interrogating the place of the conscientious individual within an oppressive system, Broken Drum is also a testament to changing times and new possibilities as the youngsters slowly find the strength to resist and insist on their right to individual happiness.

As the film begins, the family’s maid is leaving in a hurry, sick to the back teeth of the treatment she receives from the head of the household. Though she admits that the wife and children are all lovely, the husband is a tyrant and, according to her, a nouveau riche upstart, all money and no class. Tsuda (Tsumasaburo Bando), a self-made construction magnate, runs his family like a small cult and everyone is so afraid of upsetting him that they find themselves entirely unable to stand up for themselves. Times are, however, changing and Tsuda’s business is in trouble, which means his power may be waning. Denied loans all over town, he tries to railroad his eldest daughter, Akiko (Toshiko Kobayashi), into marrying a wealthy suitor, Hanada (Mitsuo Nagata), and is deaf to her cries of resistance.

Despite the rather ironical speech from the maid who describes herself as a “feminist” which is why she’s unable to put up with Tsuda’s poor conduct, stopping to tell a pregnant dog not to let anyone push her around just because she’s a girl, the world of 1949 is still an incredibly sexist one. Tsuda’s long suffering wife Kuniko (Sachiko Murase) complains that her younger daughter spends all her time rehearsing for her role as Hamlet rather than learning “useful” skills for women like cooking and housekeeping. Akiko’s suitor sides with the maid, affirming that “men should be nice to women” and making a point of telling her that all his maids love him without quite realising that what he’s just said isn’t quite as nice as he thought it was. Akiko doesn’t want to get married and she doesn’t even like Hanada, but she’s too conflicted to fully resist, unsure if she has the right to go against the “tradition” of arranged marriage. She asks her mother how she felt, and learns that she too cried every day, somehow normalising the idea that a woman’s marriage is supposed to make her miserable.

Meanwhile, Tsuda is slowly destroying his oldest son, Taro (Masayuki Mori), who has been trying to quit the family construction firm to go into business with his aunt making music boxes. Tsuda isn’t having any of it, he tells Taro that music boxes aren’t a manly occupation and that he’ll never make it on his own, but Taro has an advantage in knowing that the construction company is in a bad place and his father’s authority is weakened. He becomes the first of the children to escape by rejecting Tsuda’s influence, decamping to his aunt’s which becomes a point of refuge for the other members of the Tsuda family seeking escape.

Akiko begins to gain the courage to walk away after bonding with a painter she meets after her father was extremely rude to him on a bus, poking a hole in his canvas and then blaming it on the driver. Luckily he dropped his sketchbook which has his name, Shigeki Nonaka (Jukichi Uno), inside so she can pay him a visit to return it. Unlike the Tsuda’s, the Nonaka household is one of cheerful family warmth. They are not wealthy, but they do not particularly care. Mr & Mrs Nonaka fell in love in Paris decades ago where she was charmed by the sound of his violin while she sketched in the streets. Tsuda, angrily rejecting Akiko’s attempt to cancel the marriage, tells his wife that even if she doesn’t like him now, Hanada’s wealth will make her happy in the long run, but it’s at the Nonaka’s that she discovers “the true happiness of family”, vowing to do whatever it takes to be able to marry Shigeki with whom she has fallen in love.

Even after losing two of his children and finally alienating his wife, Tsuda fails to learn, blaming his family for the failure of his business rather than accept his old school authoritarianism is out of step with the modern world. His middle son, Heizo (Chuji Kinoshita), actually the most sympathetic of the children, has written a satirical song that likens his father to a “broken drum”, something that makes a lot of noise but is confusing and very unpleasant to listen to. It doesn’t help that Tsuda also has the habit of going into speech mode, raising his arm in a fascist salute as he barks out his orders. “Life is most miserable when there’s no one to love”, Heizo tries to warn him, calmly explaining that a family is made up of “lonely creatures” with individual lives, and that that strong connection only survives through trust and independence.

Beginning to see the light, Tsuda accepts that he’ll be deposed if he doesn’t allow his family its democratic freedoms. Undergoing a conversion worthy of Scrooge at the end of a Christmas Carol, he he suddenly realises that “you need other people to succeed in life”, and is re-embraced by his family who decide to give him a chance to be better than he’s been in the knowledge that he has no more power over them than they choose to give him.

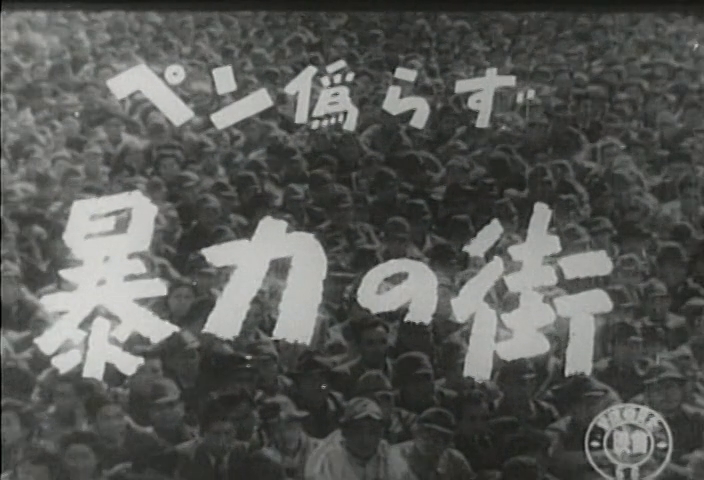

Titles and opening (no subtitles)

In the extreme turbulence of the immediate post-war period, it’s not surprising that Japan looked back to the last time it was confronted with such confusion and upheaval for clues as to how to move forward from its current state of shocked inertia. The heroine of Shiro Toyoda’s adaptation of the

In the extreme turbulence of the immediate post-war period, it’s not surprising that Japan looked back to the last time it was confronted with such confusion and upheaval for clues as to how to move forward from its current state of shocked inertia. The heroine of Shiro Toyoda’s adaptation of the

Teinosuke Kinugasa maybe best known for his avant-garde masterpiece The page of Madness even if his subsequent work leant towards a more commercial direction. His final film is just as unusual, though perhaps for different reason. In 1966, Kinugasa co-directed The Little Runaway (小さい逃亡者, Chiisai Tobosha) with Russian director Eduard Bocharov in the first of such collaborations ever created. Truth be told, aside from the geographical proximity, the Japan of 1966 could not be more different from its Soviet counterpart as the Eastern block remained mired in the “cold war” while Japan raced ahead towards its very own, capitalist, economic miracle. Perhaps looking at both sides with kind eyes, The Little Runaway has its heart in the right place with its messages of the universality of human goodness and endurance but broadly makes a success of them if failing to disguise the obvious propaganda gloss.

Teinosuke Kinugasa maybe best known for his avant-garde masterpiece The page of Madness even if his subsequent work leant towards a more commercial direction. His final film is just as unusual, though perhaps for different reason. In 1966, Kinugasa co-directed The Little Runaway (小さい逃亡者, Chiisai Tobosha) with Russian director Eduard Bocharov in the first of such collaborations ever created. Truth be told, aside from the geographical proximity, the Japan of 1966 could not be more different from its Soviet counterpart as the Eastern block remained mired in the “cold war” while Japan raced ahead towards its very own, capitalist, economic miracle. Perhaps looking at both sides with kind eyes, The Little Runaway has its heart in the right place with its messages of the universality of human goodness and endurance but broadly makes a success of them if failing to disguise the obvious propaganda gloss.

Kiju (Yoshishige) Yoshida is best remembered for his extraordinary run of avant-garde masterpieces in the late 1960s and early 1970s, but even he had to cut his teeth on Shochiku’s speciality genre – the romantic melodrama. Adapted from a best selling novel, Akitsu Springs (秋津温泉, Akitsu Onsen) is hardly an original tale in its doom laden reflection of the hopelessness and inertia of the post-war world as depicted in the frustrated love story of a self sacrificing woman and self destructive man, but Yoshida elevates the material through his characteristically beautiful compositions and full use of the particularly lush colour palate.

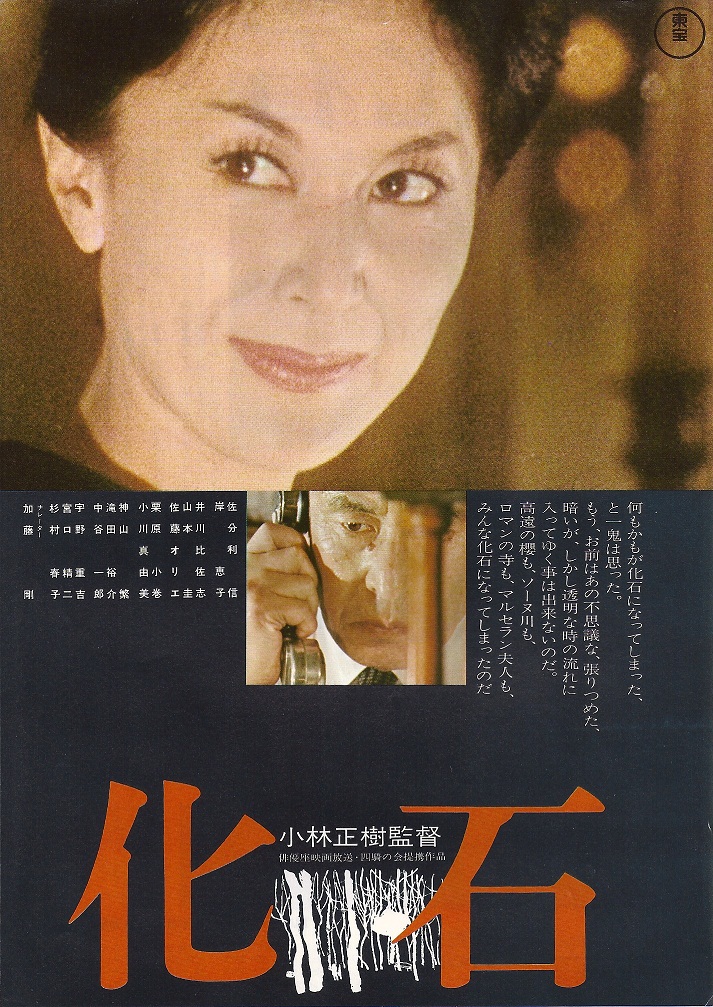

Kiju (Yoshishige) Yoshida is best remembered for his extraordinary run of avant-garde masterpieces in the late 1960s and early 1970s, but even he had to cut his teeth on Shochiku’s speciality genre – the romantic melodrama. Adapted from a best selling novel, Akitsu Springs (秋津温泉, Akitsu Onsen) is hardly an original tale in its doom laden reflection of the hopelessness and inertia of the post-war world as depicted in the frustrated love story of a self sacrificing woman and self destructive man, but Yoshida elevates the material through his characteristically beautiful compositions and full use of the particularly lush colour palate. Throughout Masaki Kobayashi’s relatively short career, his overriding concern was the place of the conscientious individual within a corrupt society. Perhaps most clearly seen in his magnum opus,

Throughout Masaki Kobayashi’s relatively short career, his overriding concern was the place of the conscientious individual within a corrupt society. Perhaps most clearly seen in his magnum opus,  Nobuhiko Obayashi takes another trip into the idol movie world only this time for Toho with an adaptation of a popular shojo manga. That is to say, he employs a number of idols within the film led by Toho’s own Yasuko Sawaguchi, though the film does not fit the usual idol movie mould in that neither Sawaguchi or the other girls is linked with the title song. Following something of a sisterly trope which is not uncommon in Japanese film or literature, Four Sisters (姉妹坂, Shimaizaka) centres around four orphaned children who discover their pasts, and indeed futures, are not necessarily those they would have assumed them to be.

Nobuhiko Obayashi takes another trip into the idol movie world only this time for Toho with an adaptation of a popular shojo manga. That is to say, he employs a number of idols within the film led by Toho’s own Yasuko Sawaguchi, though the film does not fit the usual idol movie mould in that neither Sawaguchi or the other girls is linked with the title song. Following something of a sisterly trope which is not uncommon in Japanese film or literature, Four Sisters (姉妹坂, Shimaizaka) centres around four orphaned children who discover their pasts, and indeed futures, are not necessarily those they would have assumed them to be.