Seijun Suzuki may have been fired for making films that made no sense and no money, but he had to start somewhere before getting the opportunity to push the boat out. Suzuki’s early career was much like that of any low ranking director at Nikkatsu in that he was handed a number of program pictures often intended to push a pop song or starring one of the up and coming stars in the studio’s expanding youth output. The Boy Who Came Back (踏みはずした春, Fumihazushita Haru, AKA The Spring that Never Came) is among these early efforts and marks an early leading role for later pinup star Akira Kobayashi paired with his soon to be frequent leading lady, Ruriko Asaoka. A reform school tale, the film is a restrained affair for Suzuki who keeps the rage quelled for the most part while his hero struggles ever onward in a world which just won’t let him be.

Seijun Suzuki may have been fired for making films that made no sense and no money, but he had to start somewhere before getting the opportunity to push the boat out. Suzuki’s early career was much like that of any low ranking director at Nikkatsu in that he was handed a number of program pictures often intended to push a pop song or starring one of the up and coming stars in the studio’s expanding youth output. The Boy Who Came Back (踏みはずした春, Fumihazushita Haru, AKA The Spring that Never Came) is among these early efforts and marks an early leading role for later pinup star Akira Kobayashi paired with his soon to be frequent leading lady, Ruriko Asaoka. A reform school tale, the film is a restrained affair for Suzuki who keeps the rage quelled for the most part while his hero struggles ever onward in a world which just won’t let him be.

Keiko (Sachiko Hidari) is a conductress on a tour bus, but she has aspirations towards doing good in the world and is also a member of the volunteer organisation, Big Brothers and Sisters. While the other girls are busy gossiping about one of their number who has just got engaged (but doesn’t look too happy about it), Keiko gets a message to call in to “BBS” and is excited to learn she’s earned her first assignment. Keiko will be mentoring Nobuo (Akira Kobayashi) – a young man getting out of reform school after his second offence (assault & battery + trying to throttle his father with a necktie, time added for plotting a mass escape). Nobuo, however, is an angry young man who’s done all this before, he’s not much interested in being reformed and just wants to be left alone to get back to being the cool as ice lone wolf that he’s convinced himself he really is.

Made to appeal to young men, The Boy Who Came Back has a strong social justice theme with Keiko’s well meaning desire to help held up as a public service even if her friends and family worry for her safety and think she’s wasting her time on a load of ne’er do wells. Apparently an extra-governmental organisation, BBS has no religious agenda but is committed to working with troubled young people to help them overcome their problems and reintegrate into society.

Reintegration is Nobuo’s biggest problem. He’s committed to going straight but he’s proud and unwilling to accept the help of others. He turns down Keiko’s offer to help him find work because he assumes it will be easy enough to find a job, but there are no jobs to be had in the economically straightened world of 1958 – one of the reasons Keiko’s mother thinks the BBS is pointless is because no matter how many you save there will always be more tempted by crime because of the “difficult times”. When he calms down and comes back, agreeing to an interview for work at his mother’s factory Nobuo leaves in a rage after an employee gives him a funny look. There are few jobs for young men, but there are none for “punks” who’ve been in juvie. Every time things are looking up for Nobuo, his delinquent past comes back to haunt him.

This is more literally true when an old enemy re-enters Nobuo’s life with the express intention of derailing it. His punk buddies don’t like it that he’s gone straight, and his arch rival is still after Nobuo’s girl, Kazue (Ruriko Asaoka). If Nobuo is going to get “reformed” he’ll have to solve the problem with Kajita (Jo Shishido) and his guys, but if he does it in the usual way, he’ll land up right in the slammer. Keiko’s dilemma is one of getting too involved or not involved enough – she needs to teach Nobuo to fix his self image issues (which are largely social issues too seeing as they relate to familial dysfunction – a violent father and emotionally distant mother creating an angry, fragile young man who thinks he’s worthless and no one will ever really love him) for himself, rather than try to fix them for him.

A typical program picture of the time, The Boy Who Came Back does not provide much scope for Suzuki’s rampant imagination, but it does feature his gift for unusual framing and editing techniques as well as his comparatively more liberal use of song and dance sequences in the (not quite so sleazy) bars and cabarets that Nobuo and his ilk frequent. Unlike many a Nikkatsu youth movie, The Boy Who Came Back has a happy ending as everyone, including the earnest Keiko, learns to sort out their various difficulties and walks cheerfully out into the suddenly brighter future with a much more certain footing.

The Boy Who Came Back is the first of five films included in Arrow’s Seijun Suzuki: The Early Years. Vol. 1 Seijun Rising: The Youth Movies box set.

Original trailer (English subtitles)

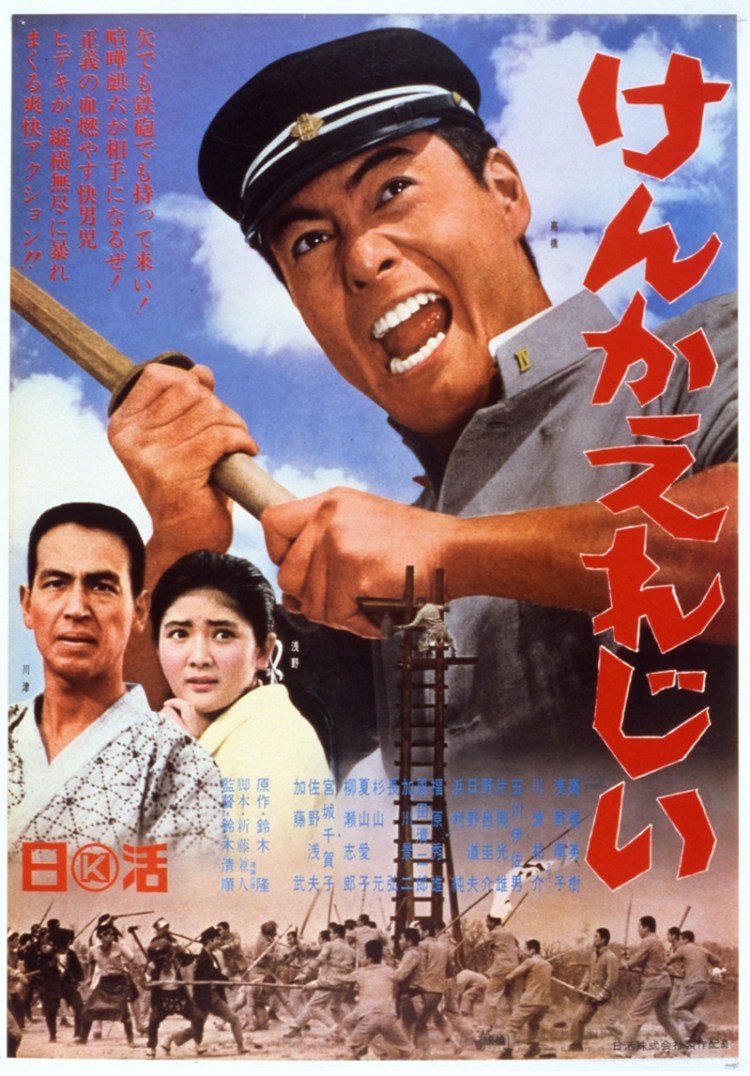

Ah, youth. It explains so many things though, sadly, only long after it’s passed. For the young men who had the misfortune to come of age in the 1930s, their glory days are filled with bittersweet memories as their personal development occurred against a backdrop of increasing political division. Seijun Suzuki was not exactly apolitical in his filmmaking despite his reputation for “nonsense”, but in Fighting Elegy (けんかえれじい, Kenka Elegy) he turns a wry eye back to his contemporaries for a rueful exploration of militarism’s appeal to the angry young man. When emotion must be sublimated and desire repressed, all that youthful energy has to go somewhere and so the unresolved tensions of the young men of Japan brought about an unwelcome revolution in a misguided attempt at mastery over the self.

Ah, youth. It explains so many things though, sadly, only long after it’s passed. For the young men who had the misfortune to come of age in the 1930s, their glory days are filled with bittersweet memories as their personal development occurred against a backdrop of increasing political division. Seijun Suzuki was not exactly apolitical in his filmmaking despite his reputation for “nonsense”, but in Fighting Elegy (けんかえれじい, Kenka Elegy) he turns a wry eye back to his contemporaries for a rueful exploration of militarism’s appeal to the angry young man. When emotion must be sublimated and desire repressed, all that youthful energy has to go somewhere and so the unresolved tensions of the young men of Japan brought about an unwelcome revolution in a misguided attempt at mastery over the self. Before Seijun Suzuki pushed his luck too far with the genre classic

Before Seijun Suzuki pushed his luck too far with the genre classic

What are you supposed to do when you’ve lost a war? Your former enemies all around you, refusing to help no matter what they say and there are only black-marketers and gangsters where there used to be merchants and craftsmen. Everyone is looking out for themselves, everyone is in the gutter. How are you supposed to build anything out of this chaos? Perhaps you aren’t, but you have to go one living, somehow. The picture of the immediate post-war world which Suzuki paints in Gate of Flesh (肉体の門, Nikutai no Mon) is fairly hellish – crowded, smelly marketplaces thronging with desperate people. Based on a novel by Taijiro Tamura (who also provided the source material for Suzuki’s Story of a Prostitute), Gate of Flesh has its lens firmly pointed at the bottom of the heap and resolutely refuses to avert its gaze.

What are you supposed to do when you’ve lost a war? Your former enemies all around you, refusing to help no matter what they say and there are only black-marketers and gangsters where there used to be merchants and craftsmen. Everyone is looking out for themselves, everyone is in the gutter. How are you supposed to build anything out of this chaos? Perhaps you aren’t, but you have to go one living, somehow. The picture of the immediate post-war world which Suzuki paints in Gate of Flesh (肉体の門, Nikutai no Mon) is fairly hellish – crowded, smelly marketplaces thronging with desperate people. Based on a novel by Taijiro Tamura (who also provided the source material for Suzuki’s Story of a Prostitute), Gate of Flesh has its lens firmly pointed at the bottom of the heap and resolutely refuses to avert its gaze. Never one to be accused of clarity, Seijun Suzuki’s Capone Cries a Lot (カポネおおいになく, Capone Ooni Naku) is one of his most cheerfully bizarre movies coming fairly late in his career yet and neatly slotting itself in right after Suzuki’s first two Taisho era movies,

Never one to be accused of clarity, Seijun Suzuki’s Capone Cries a Lot (カポネおおいになく, Capone Ooni Naku) is one of his most cheerfully bizarre movies coming fairly late in his career yet and neatly slotting itself in right after Suzuki’s first two Taisho era movies,