Seemingly drawing influence from the series of Arabian fantasy films from Hollywood, Senkichi Taniguchi’s Lost World of Sinbad: Samurai Pirate (大盗賊, Dai Tozoku), sees the director reunite with Toshiro Mifune who had made his debut in the director’s Snow Trail which could not be more different from this crowd-pleasing adventure movie. The film is loosely based on the life of 16th century merchant Luzon Sukezaemon who eventually fled to Cambodia after all his possessions were seized by Hideyoshi Toyotomi and he was condemned on some trumped up charges.

The film’s opening scenes perhaps reflect this incident as Luzon (Toshiro Mifune) is branded a pirate and set to be burned at the stake, narrowly escaping after bribing an official with drugs. Resentful, Luzon decides he might as well become a pirate after all as he’s pretty sick of Japan and fancies seeking his fortune on the open seas only his ship is quickly destroyed in a storm and all his crew killed while the treasure he was carrying is seized by the fearsome Black Pirate (Makoto Sato). Washing up in a mysterious place aesthetically a mashup between South East Asia and the Middle East, Luzon is cared for by a hermit and then becomes embroiled in intrigue on finding out that the tyrannical king has been seizing local women in exchange for unpaid taxes and imprisoning them within his harem.

Luzon’s dreams are for riches and status so his sudden discovery of a love of justice is a bit of a surprise, but then he’s also most interested in the princess Yaya (Mie Hama) because he spotted one the necklaces from his treasure chest around her neck which suggests she might have a lead on the Black Pirate. Princess Yaya is engaged to a prince from the Ming kingdom which threatens a wider kind of geopolitical destabilisation should anything go wrong with this marriage which is a distinct possibility seeing as the corrupt Chancellor (Tadao Nakamaru) has been colluding with an evil witch to kill the king and seize the kingdom.

Rather than a pure pirate movie the film contains fantasy elements such as the presence of a Western-style castle which is clearly modelled on the one from Disney’s Snow White along with a weird hermit whose powers are weakened every time he sees an attractive woman. It is not, however, the kind of tokusatsu the English title bestowed by the US release implies as it contains no real monsters instead focussing its special effects on the magic used by the witch, who can turn people to stone with her eyes, and the hermit who can turn himself into a fly or disappear in a puff of blue smoke. Despite the prominent inclusion of SFX master Eiji Tsuburaya these effects are repeated several times are really the only ones featured in the film.

In any case, what’s in play is famous merchant Luzon’s redemption arc in which he recovers the treasure but gives it back to the people, symbolically abandoning his dreams of wealth and status for something a little more community minded in vowing to sail the seven seas pursuing justice throughout the world. Having been a victim of authoritarianism in Japan, he rises up against tyranny abroad while teaming up with a group of local bandits and several times proudly proclaiming himself as Japanese though in a movie conceit everyone speaks his language including the Black Pirate who is later exposed as a snivelling fool tricked by the Chancellor on the promise of a chance to marry the Princess Yaya. Most of the derring do is reserved for the final sequence in which Luzon and the bandits storm the castle to defeat the evil chancellor but the screenplay also packs in genre elements such as trap doors and secret dungeons which keep Luzon busy as he does his best to overthrow an oppressive regime if only to put the rightful king back on the throne in the hope that might be better. Taniguchi certainly makes the most of his elaborate sets and costumes, creating a sense of tempered opulence along Middle-Eastern themes while adding a touch of the mythic in the attempt to weave a legend around the real life figure of Luzon Sukezaemon as a bandit revolutionary selling dreams of freedom on the sea as a pirate more interested in justice than money in otherwise corrupt society.

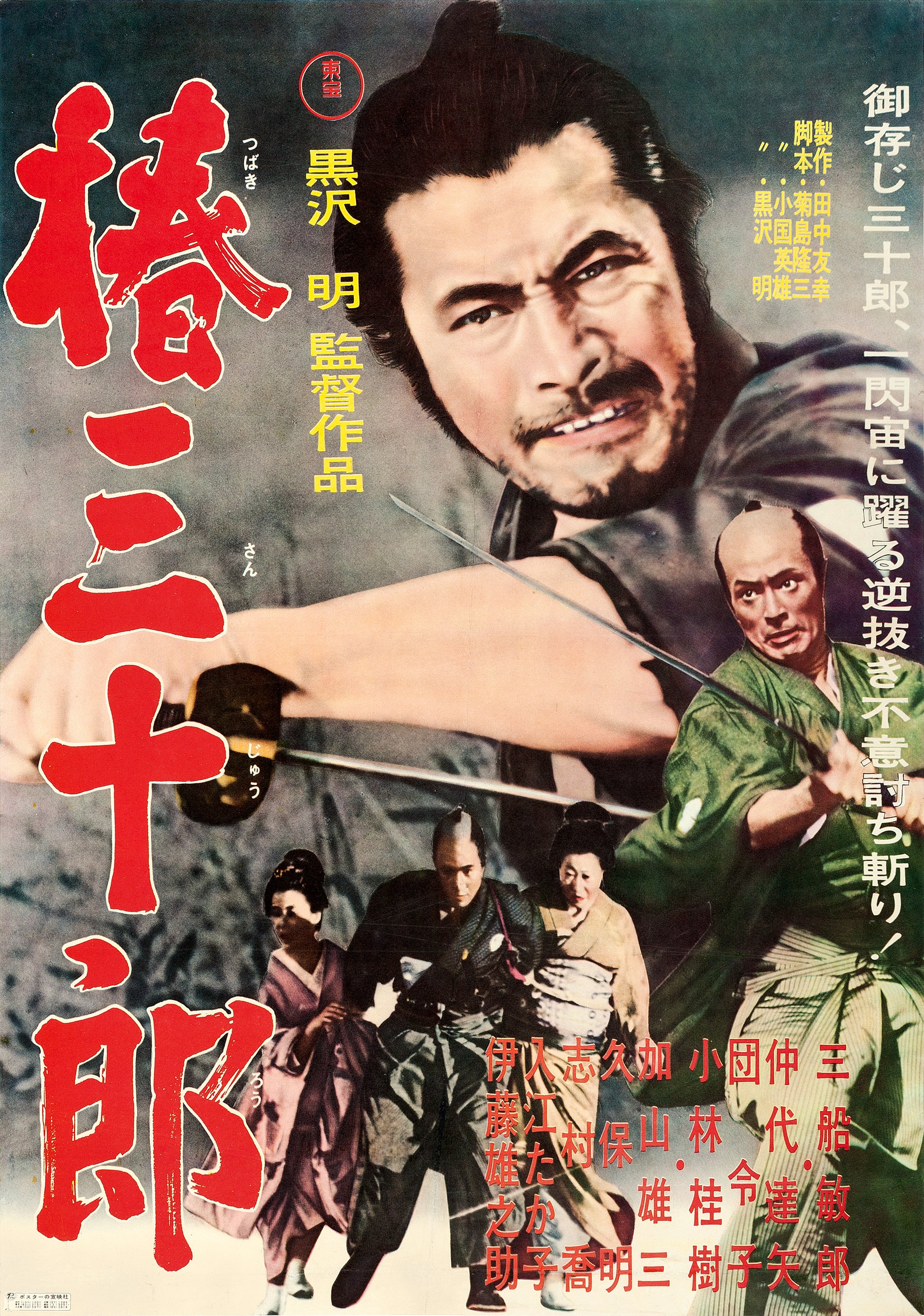

Despite a long and hugely successful career which saw him feted as the man who’d put Japanese cinema on the international map, Akira Kurosawa’s fortunes took a tumble in the late ‘60s with an ill fated attempt to break into Hollywood. Tora! Tora! Tora! was to be a landmark film collaboration detailing the attack on Pearl Harbour from both the American and Japanese sides with Kurosawa directing the Japanese half, and an American director handling the English language content. However, the American director was not someone the prestigious caliber of David Lean as Kurosawa had hoped and his script was constantly picked apart and reduced.

Despite a long and hugely successful career which saw him feted as the man who’d put Japanese cinema on the international map, Akira Kurosawa’s fortunes took a tumble in the late ‘60s with an ill fated attempt to break into Hollywood. Tora! Tora! Tora! was to be a landmark film collaboration detailing the attack on Pearl Harbour from both the American and Japanese sides with Kurosawa directing the Japanese half, and an American director handling the English language content. However, the American director was not someone the prestigious caliber of David Lean as Kurosawa had hoped and his script was constantly picked apart and reduced. Based on the contemporary manga by the legendary Fujiko F. Fujio (Doraemon), Future Memories: Last Christmas (未来の想い出 Last Christmas, Mirai no Omoide: Last Christmas) is neither quiet as science fiction or romantically focussed as the title suggests yet perhaps reflects the mood of its 1992 release in which a generation of young people most probably would also have liked to travel back in time ten years just like the film’s heroines. Another up to the minute effort from the prolific Yoshimitsu Morita, Future Memories: Last Christmas is among his most inconsequential works, displaying much less of his experimental tinkering or stylistic variations, but is, perhaps a guide its traumatic, post-bubble era.

Based on the contemporary manga by the legendary Fujiko F. Fujio (Doraemon), Future Memories: Last Christmas (未来の想い出 Last Christmas, Mirai no Omoide: Last Christmas) is neither quiet as science fiction or romantically focussed as the title suggests yet perhaps reflects the mood of its 1992 release in which a generation of young people most probably would also have liked to travel back in time ten years just like the film’s heroines. Another up to the minute effort from the prolific Yoshimitsu Morita, Future Memories: Last Christmas is among his most inconsequential works, displaying much less of his experimental tinkering or stylistic variations, but is, perhaps a guide its traumatic, post-bubble era.